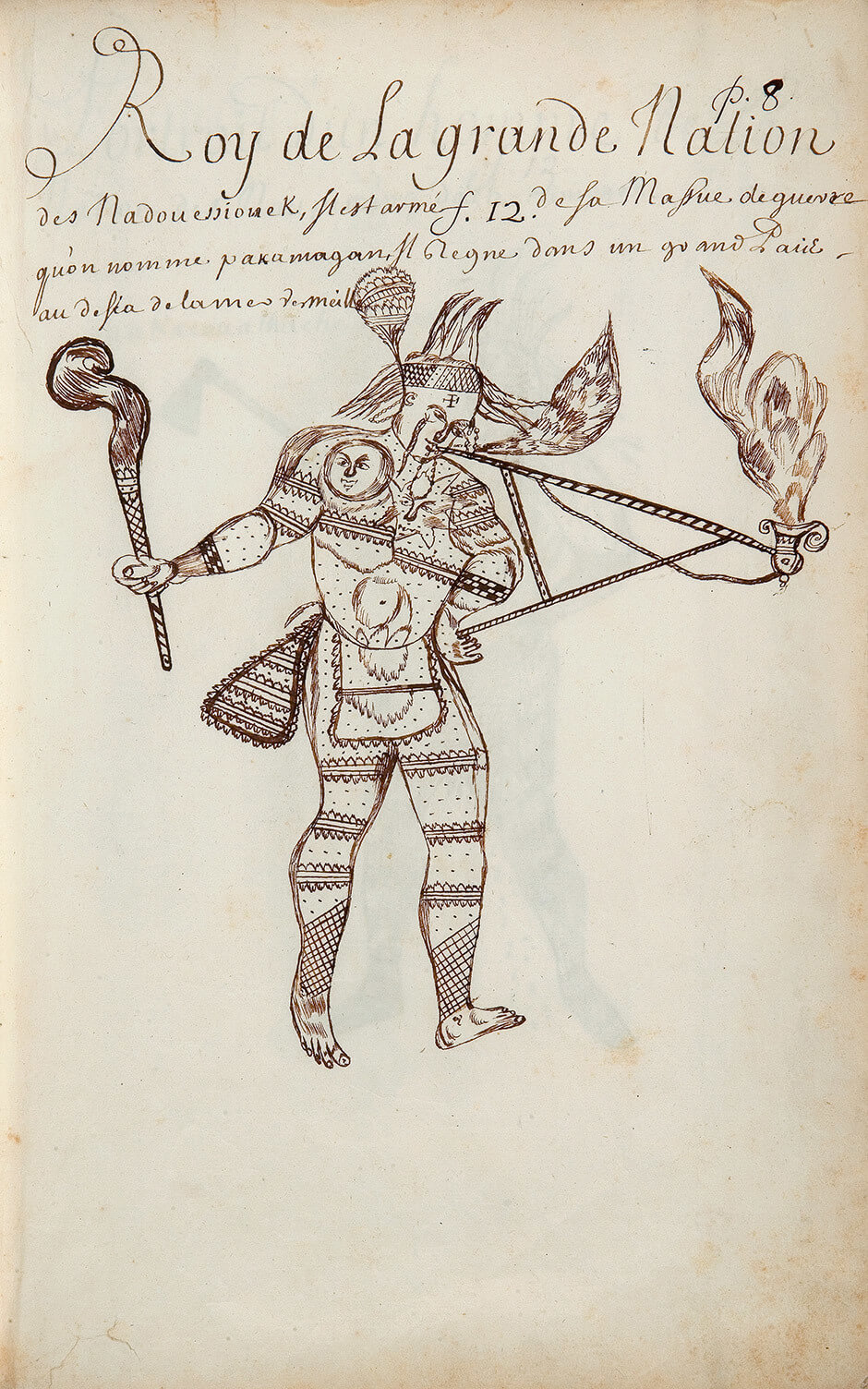

King of the Great Nation of the Nadouessiouek n.d.

Louis Nicolas, King of the Great Nation of the Nadouessiouek (Roy de La grande Nation des Nadouessiouek), n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm

Codex Canadensis, page 8

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

According to the caption, this drawing represents the “King of the great nation of the Nadouessiouek [Sioux people] . . . armed with his war club, which is called pakamagan. He reigns in a great country beyond the Vermilion Sea [the Gulf of Mexico]” It is one of several images Nicolas created that represent the various groups he encountered during his extensive travels as a missionary in New France.

These drawings are not portraits in the usual sense of the word—accurate portrayals of particular individuals; rather, they represent “types.” They are significant, however, because they present rare images of the body paintings, clothing, hairstyles, and implements (fishing and hunting tools, weapons, pipes, tobacco pouches) used by Indigenous peoples in the latter seventeenth century. Archaeologists have unearthed the bowls of many ceramic pipes, for instance, but none of the reeds that Nicolas represents here.

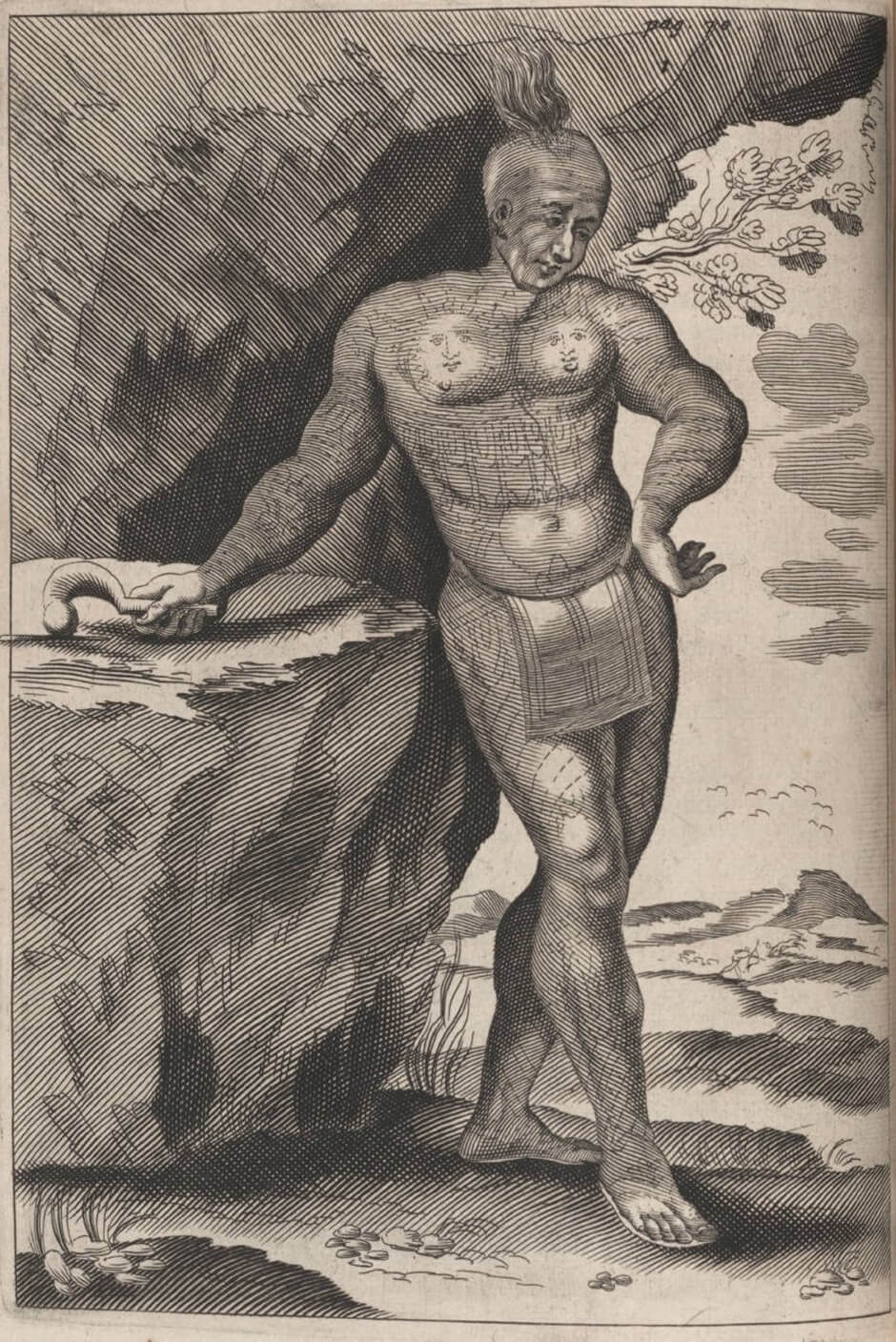

This drawing bears a striking resemblance to an image of an Indigenous warrior found in The History of Canada, or of New France (Historiae Canadensis seu Novae Franciae Libri Decem) (1664), a text written by Father François Du Creux

(1596–1666). Nicolas often took the outlines of human and animal figures from published sources, and the pose and proportions of five of his portraits are clearly based on engravings found in Du Creux. In each case he modified the details to fit with his own observations—and he claimed proudly that he had seen everything he recorded. In this image, the standing hairstyle, the club in the right hand, the position of the left arm, and the figure of the sun and the moon painted on the chest are similar in both Du Creux’s and Nicolas’s figures, but Nicolas gives his king an elaborately constructed and decorated pipe that spews flames and smoke. At the time it was common for both writers and illustrators of works on natural history to copy or derive inspiration from texts and engravings that had been published previously—usually without any attribution at all.

Nicolas likely encountered the Sioux when he was at Chequamegon, at the southwest end of Lake Superior, in 1667–68. The Sioux were enemies of the Ottawas, who, according to Father Claude Dablon, were well established at Chequamegon. Despite this hostility, the Sioux still visited Chequamegon “in small numbers” to trade and to fish. Nicolas, eager to record as many of his observations and experiences as he could, took advantage of the mingling of different groups at this and other trading stations.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements