Since Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald considered style and technique to be only the means to express what the artist needed to say, he used a variety of technical approaches and a wide range of media to articulate his artistic vision. He used subject matter offered by his immediate surroundings to experiment relentlessly with ways to communicate meaning in his art.

Commercial Beginnings

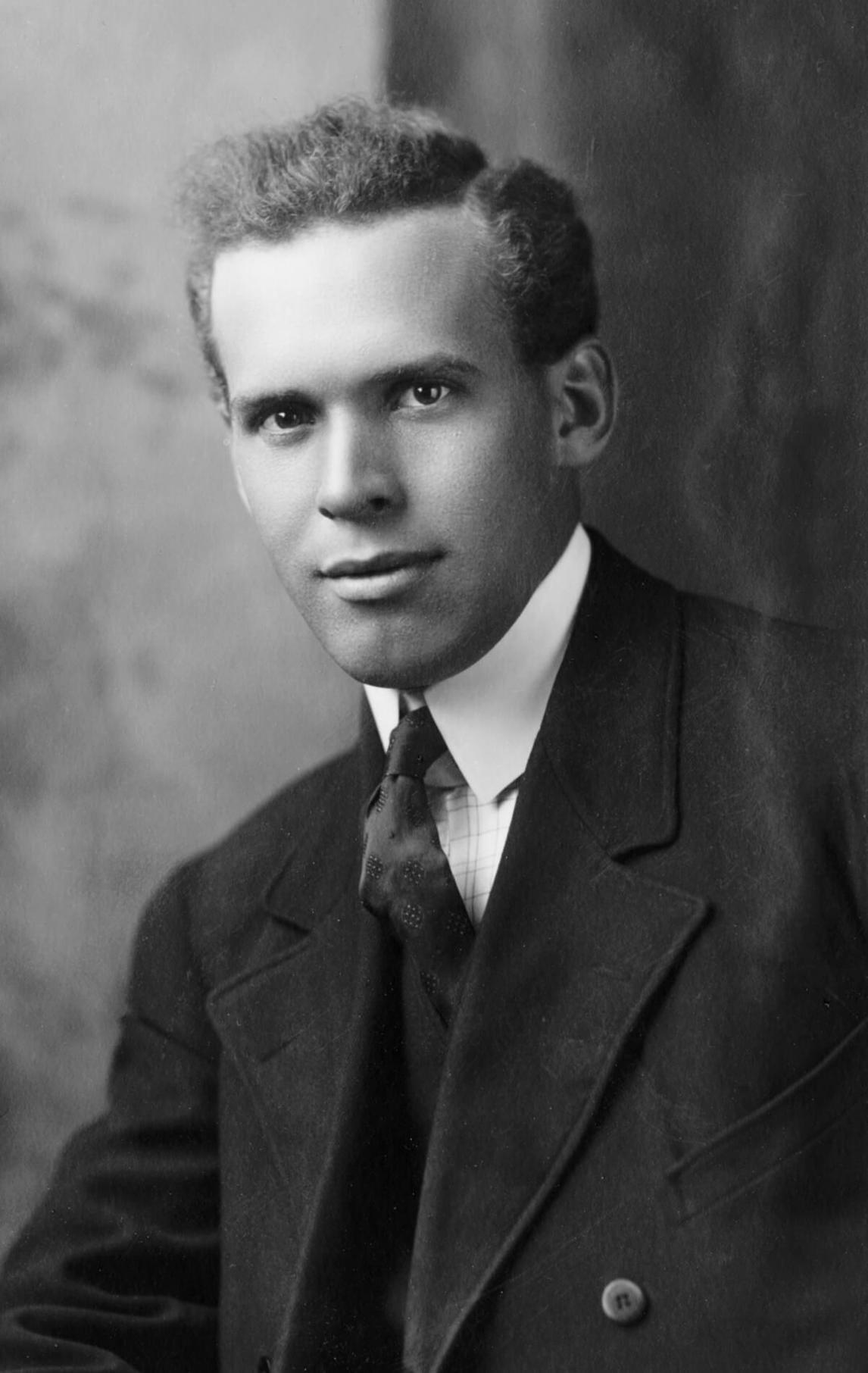

For Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald and many of his contemporaries, including members of the Group of Seven, finding employment in a commercial enterprise was the starting point for a career in art. Indeed an income from the commerce of art was often a necessary means for survival. In an autobiographical statement written when he was fifty, FitzGerald recalled his beginnings in the art world: “During the fall of 1912, I joined the art department of an advertising firm, and was married. This was the beginning of nine years spent in a wide variety of work, including advertising drawings, mural paintings and sketches for interior decorations, posters and window backgrounds, stage scenery, lettering and so on.”

Here, FitzGerald refers to the period up to 1921, the year he left Winnipeg to study at the Art Students League of New York. While precise details of this early work history remain unknown, FitzGerald may have been employed for part of this time by the Stovel Company Limited, an engraving, lithography, and printing firm in Winnipeg. Curiously, he was never engaged by the major photo-engraving and printing firm, Brigdens of Winnipeg Limited, which opened a Winnipeg branch of their Toronto operation in 1914.

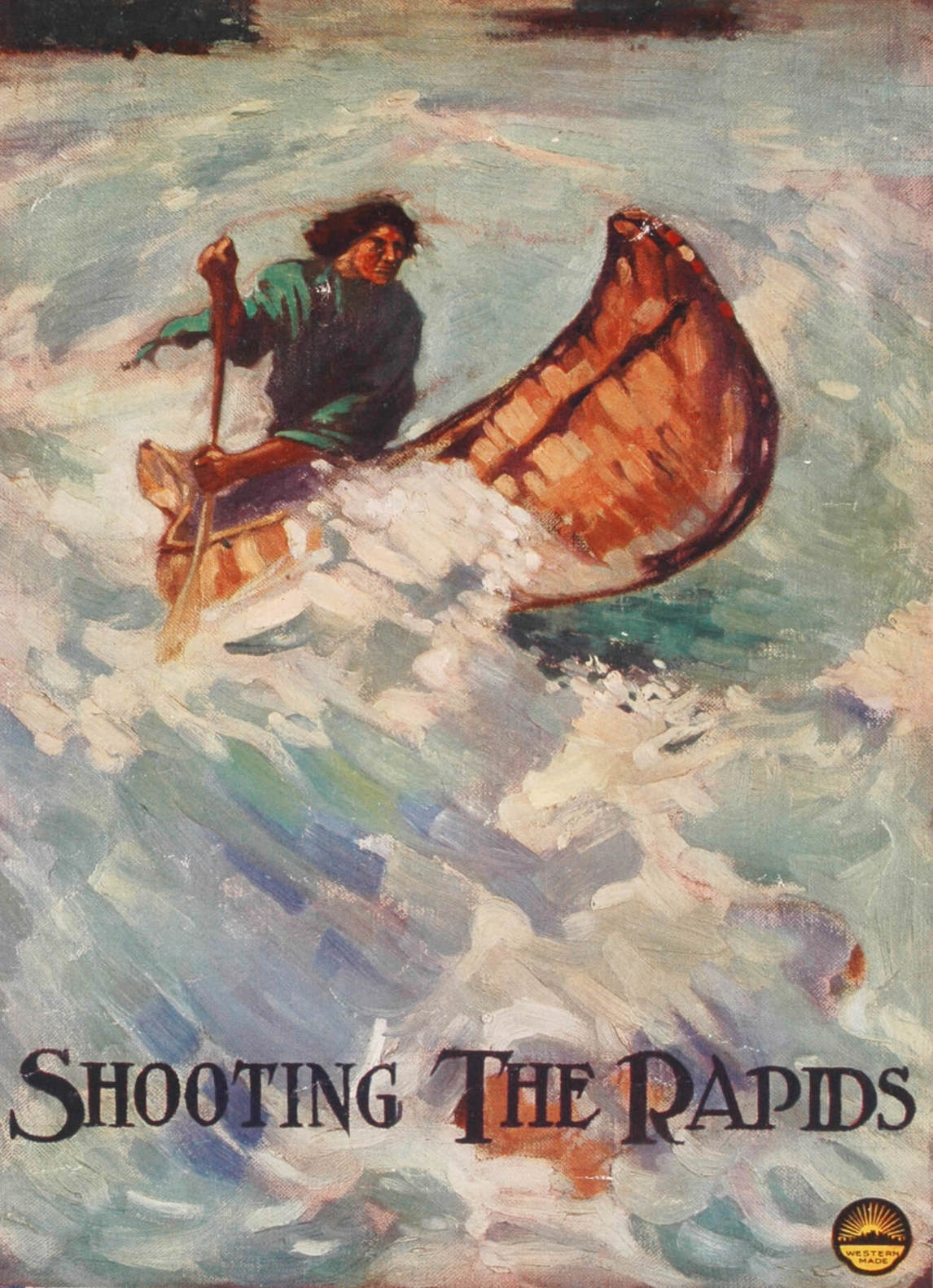

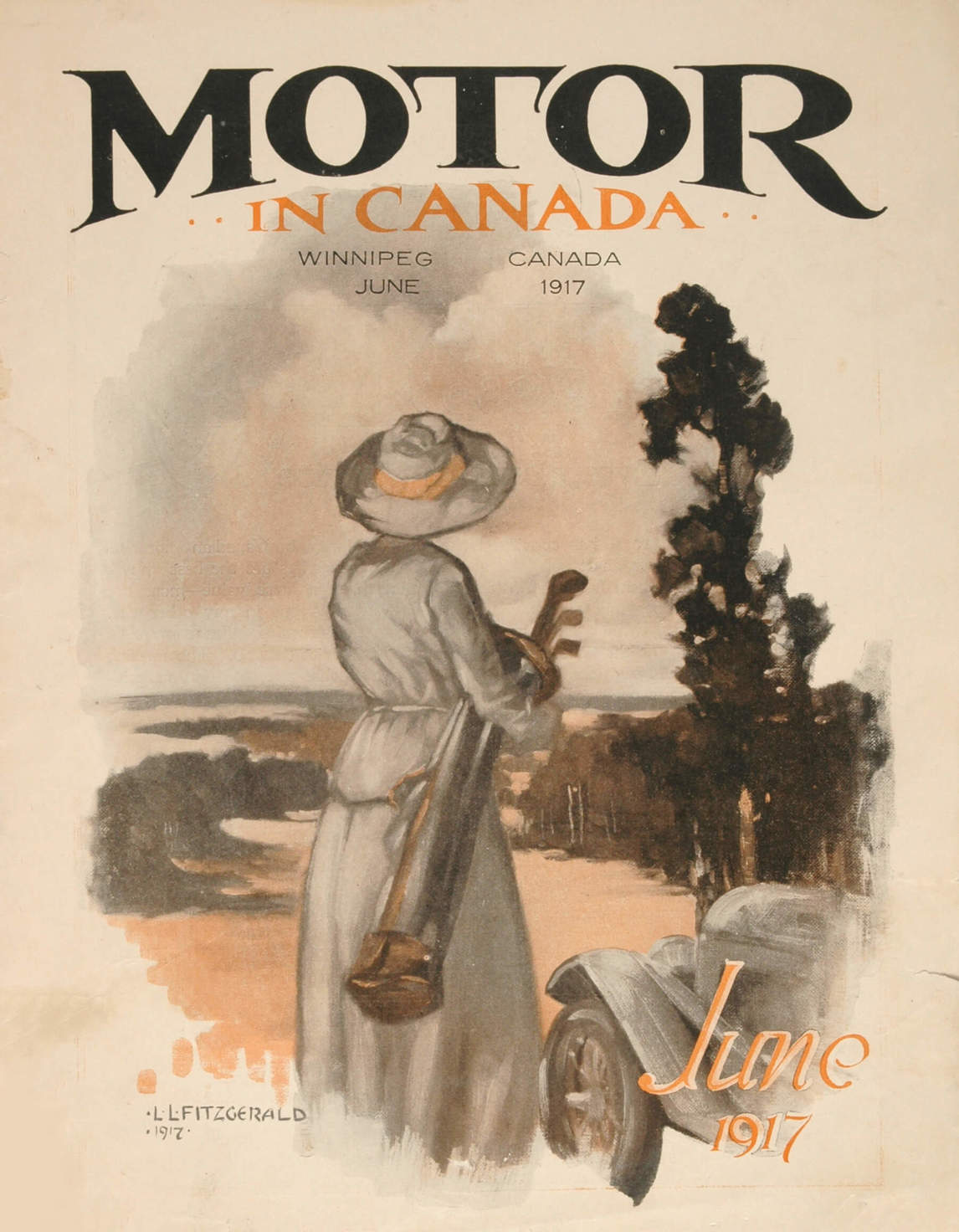

By February 1918, FitzGerald was employed in the display department of the T. Eaton Company Limited, where he worked designing window and interior displays as well as the annual Christmas parade. Although he considered his $30-a-week wage “slavery,” it is evident that he gained much valuable experience in various commercial modes of expression and media. The artist diligently recorded his freelance assignments from around this period in an account book. In December 1915 he designed a number of scribbler covers for John Gibb of Clark Brothers and Company and received $10 for Shooting the Rapids, c. 1915, copied from a painting he likely discovered reproduced in Harper’s Monthly by American illustrator Frank Schoonover (1877–1972). Magazine covers for Motor and Sport and Motor in Canada, which brought $20 each, followed in 1917. This increased significantly to $75 for the December 3, 1919, cover of The Grain Growers’ Guide. FitzGerald was also commissioned that year by the Canadian Pacific Railway, which paid him $15 each for posters with titles such as Lake Louise, Winnipeg Beach, Great Lakes Service, Lake of the Woods, Big Outdoors, Motor on Pacific Coast, and Golf on Pacific Coast—all yet to be identified, if they are extant.

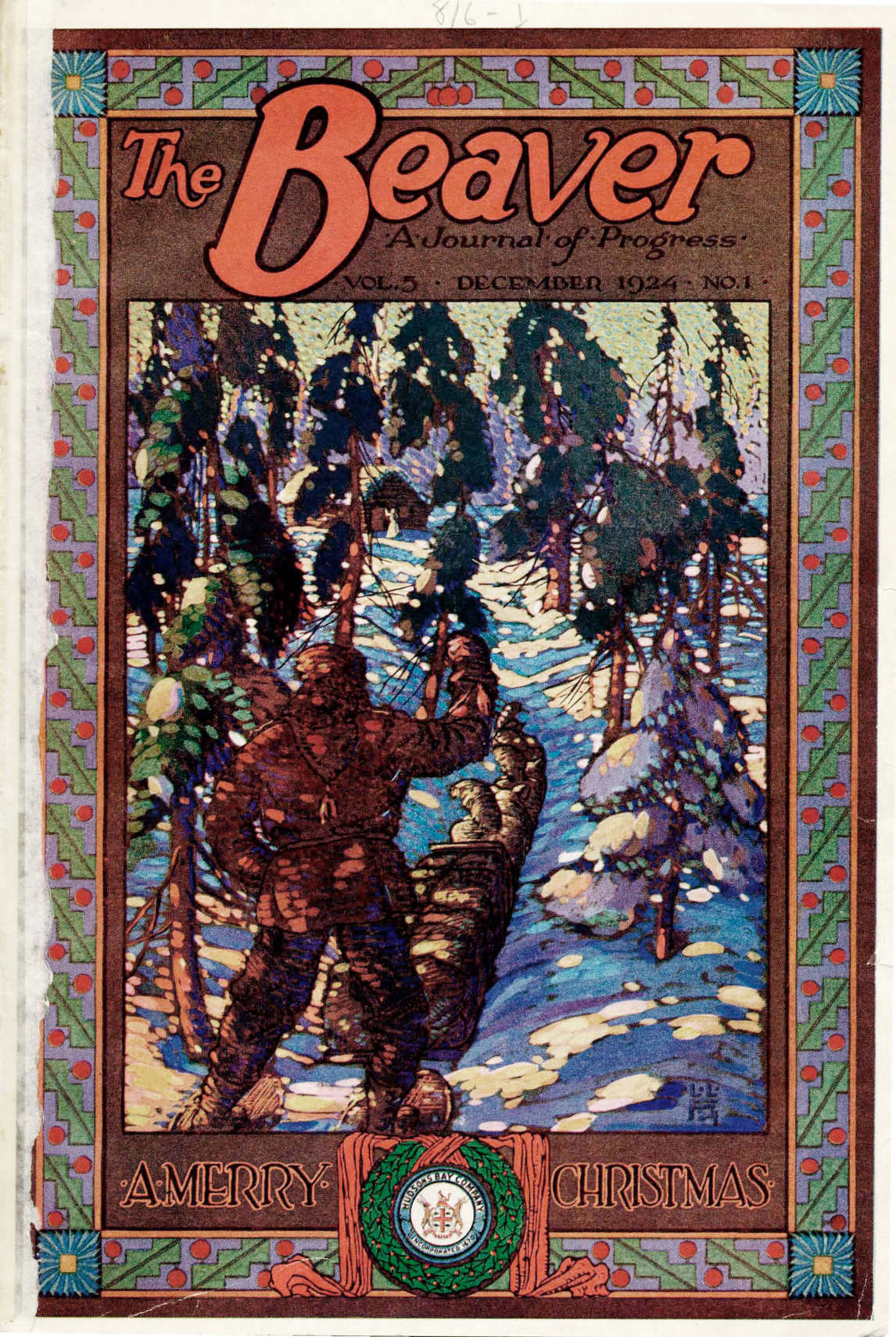

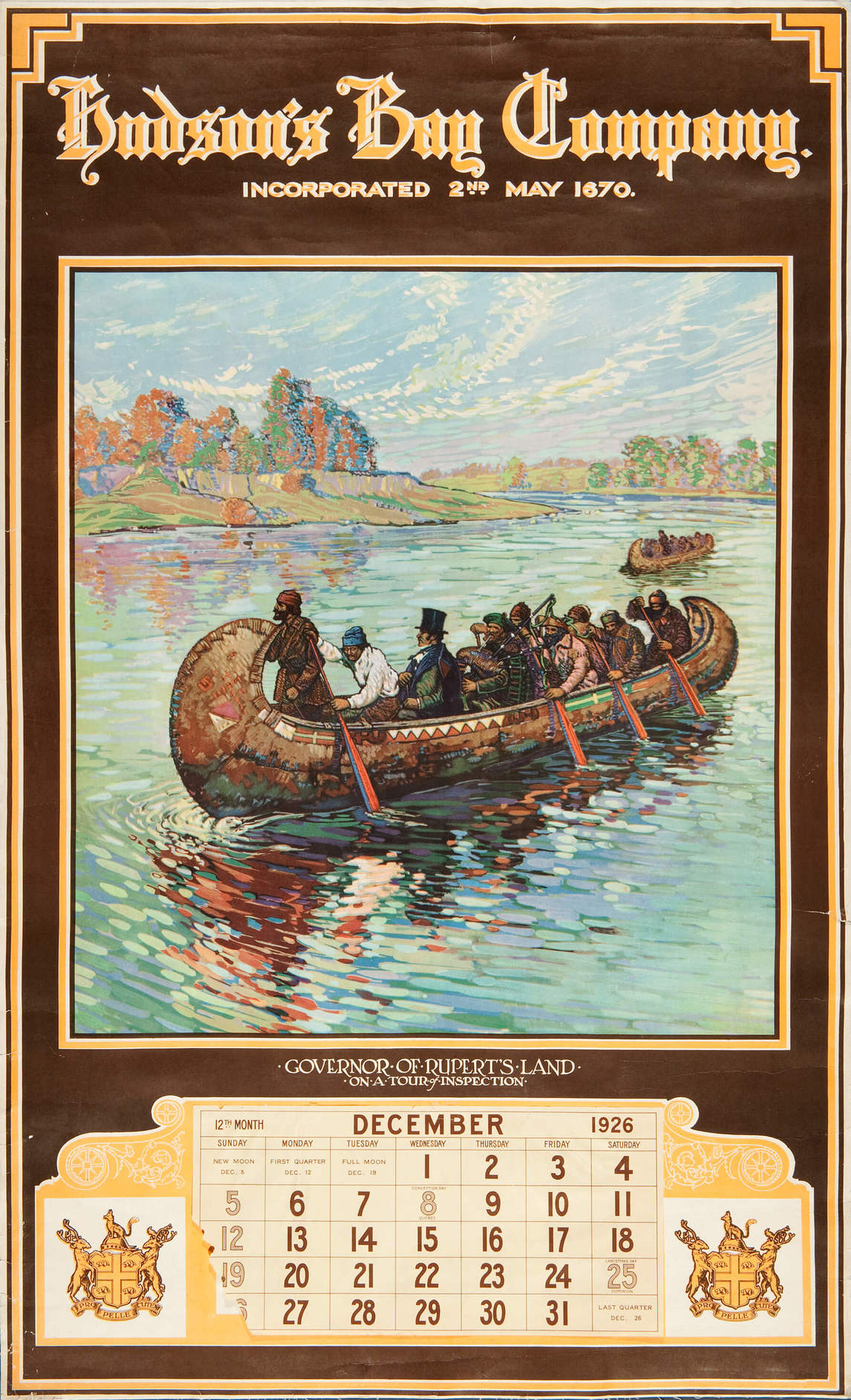

FitzGerald continued to freelance commercially after he began teaching at the Winnipeg School of Art in 1924, most notably for the Hudson’s Bay Company. He created the December 1924 cover of the company’s magazine, The Beaver; two years later, FitzGerald designed the Bay’s 1926 calendar with a Post-Impressionist-like interpretation of a painting by Cyrus C. Cuneo (1879–1916).

FitzGerald gained a tremendous technical knowledge of how to work in a wide range of media during his years in the commercial art world. Although he limited his repertory of fine art subject matter principally to landscape and still life, the artist was open throughout his career to investigating a vast array of modes and means of expression.

I have worked in many mediums, oils, water colors, pastels, pencil, pen and ink, etching and dry point [sic], lithography, engraving on wood and metal, wood carving and carving in stone and so on but the medium I prefer seems the one I am working with at the time. However, the greater proportions of my work has been done in oils, water colors and pencil, so if there is any preference these are the ones. Each medium has its special appeal and each has its short comings [sic] and particular advantages and it is good to experiment with them all if for no other reason than to find the characteristics of each one.

Avant-garde Modernism

FitzGerald expanded his knowledge of painting technique when exposed to advanced modern art while a student at the Art Students League of New York from 1921 to 1922. His New York experience was startling enough for him to describe it as “a sudden jolt into everything.” Up to that point, FitzGerald had worked through various European influences (Barbizon, Hague School, and Impressionism) before discovering the work of major Post-Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Georges Seurat (1859–1891), and Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). Although it is not known precisely what he saw in New York, it is highly likely that he gained some first-hand knowledge of Cézanne and other Post-Impressionist artists during this period, possibly at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (now the Brooklyn Museum of Art).

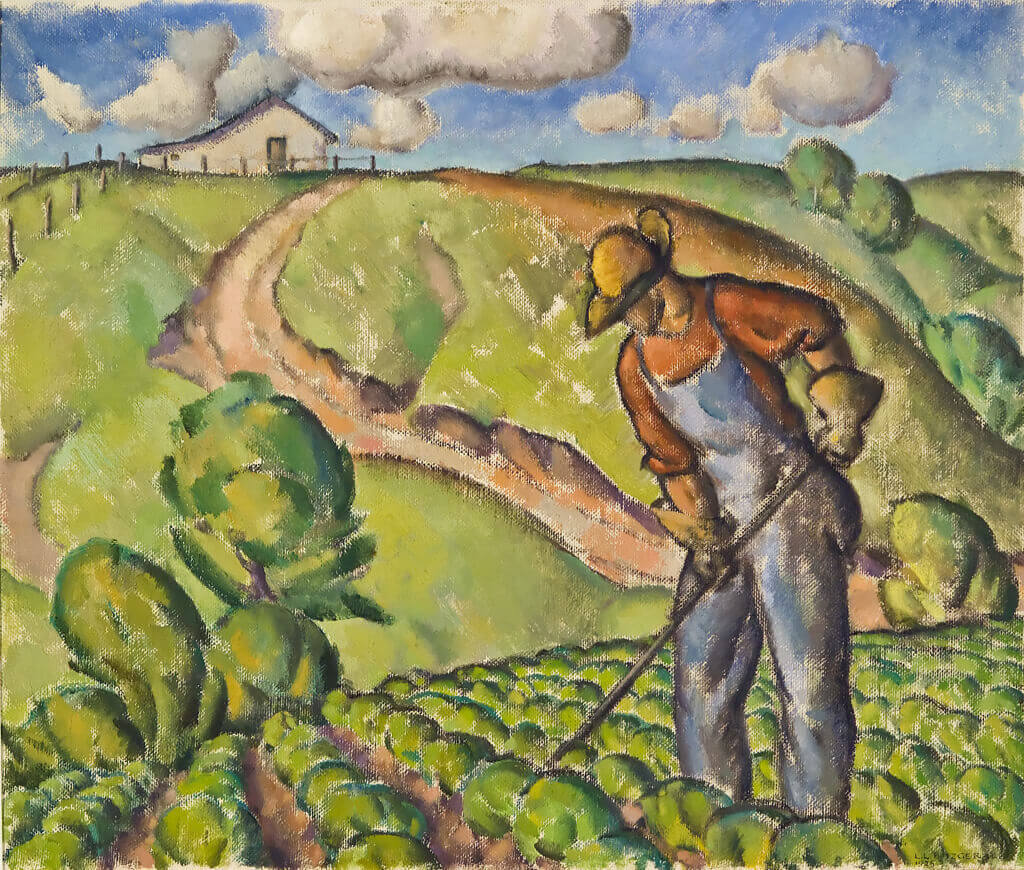

FitzGerald struggled to absorb these modern influences into his painting while finding his own way to be original. The Harvester, c. 1921, points to van Gogh not only in terms of subject matter but also in the way that colour is applied. Here, FitzGerald adopts van Gogh’s vigorous, slashing brushstrokes and his use of primary colours. The complementary contrast of blue and orange, also found in many paintings by van Gogh, is deployed boldly to define shadows.

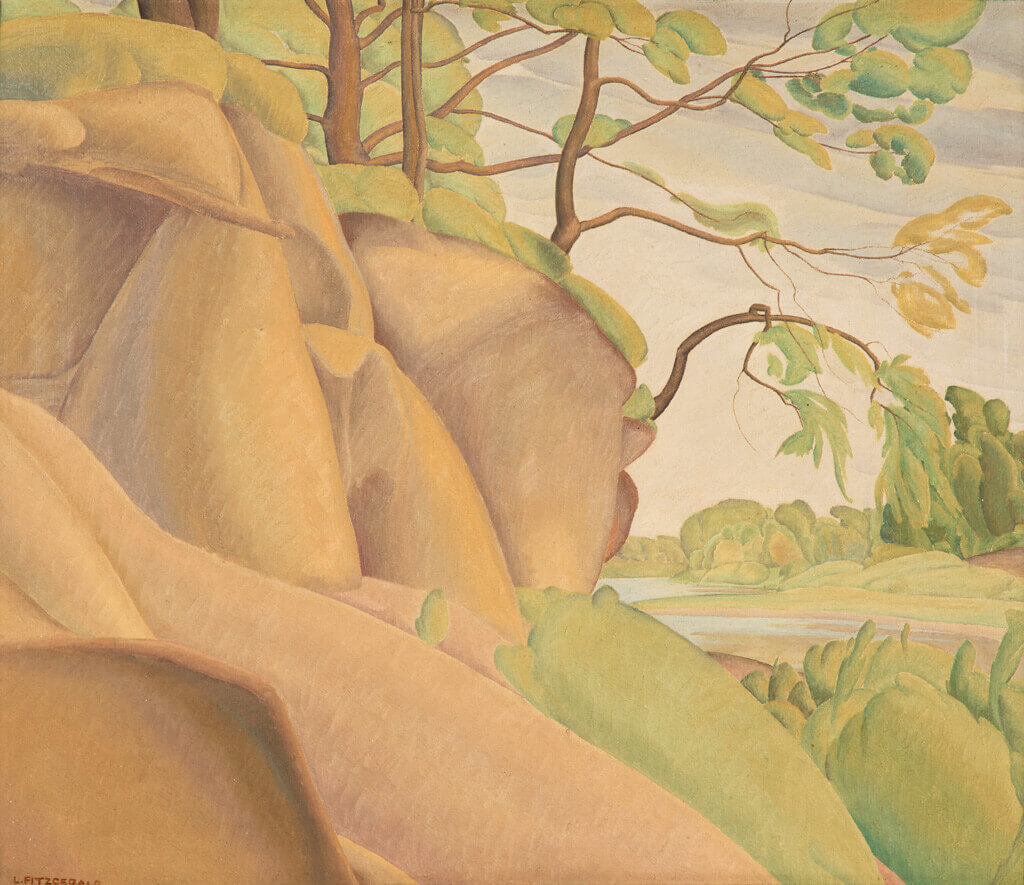

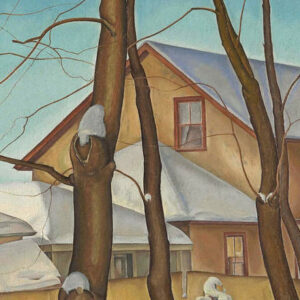

A few years later, Potato Patch, Snowflake, 1925, exhibits a limited range of colours scrubbed on to the canvas so that the bare weave shows through—an unfinished look characteristic of many paintings by Cézanne. By the early 1930s FitzGerald had developed his own style in works such as Doc Snyder’s House, 1931, and Assiniboine River, 1931. The latter painting is composed of a limited palette applied evenly so that no individual brush stroke is evident, a hallmark of his mature painting style from the early 1930s.

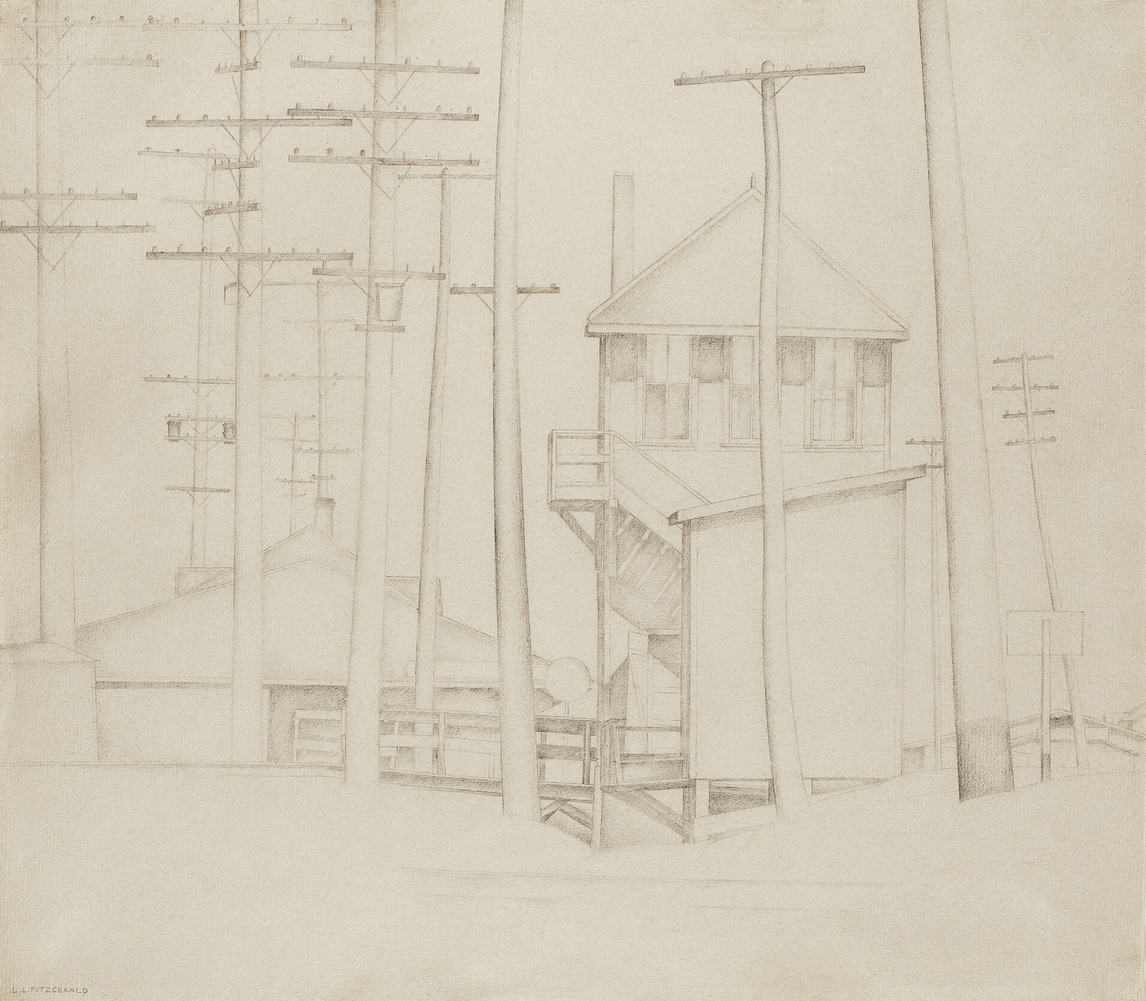

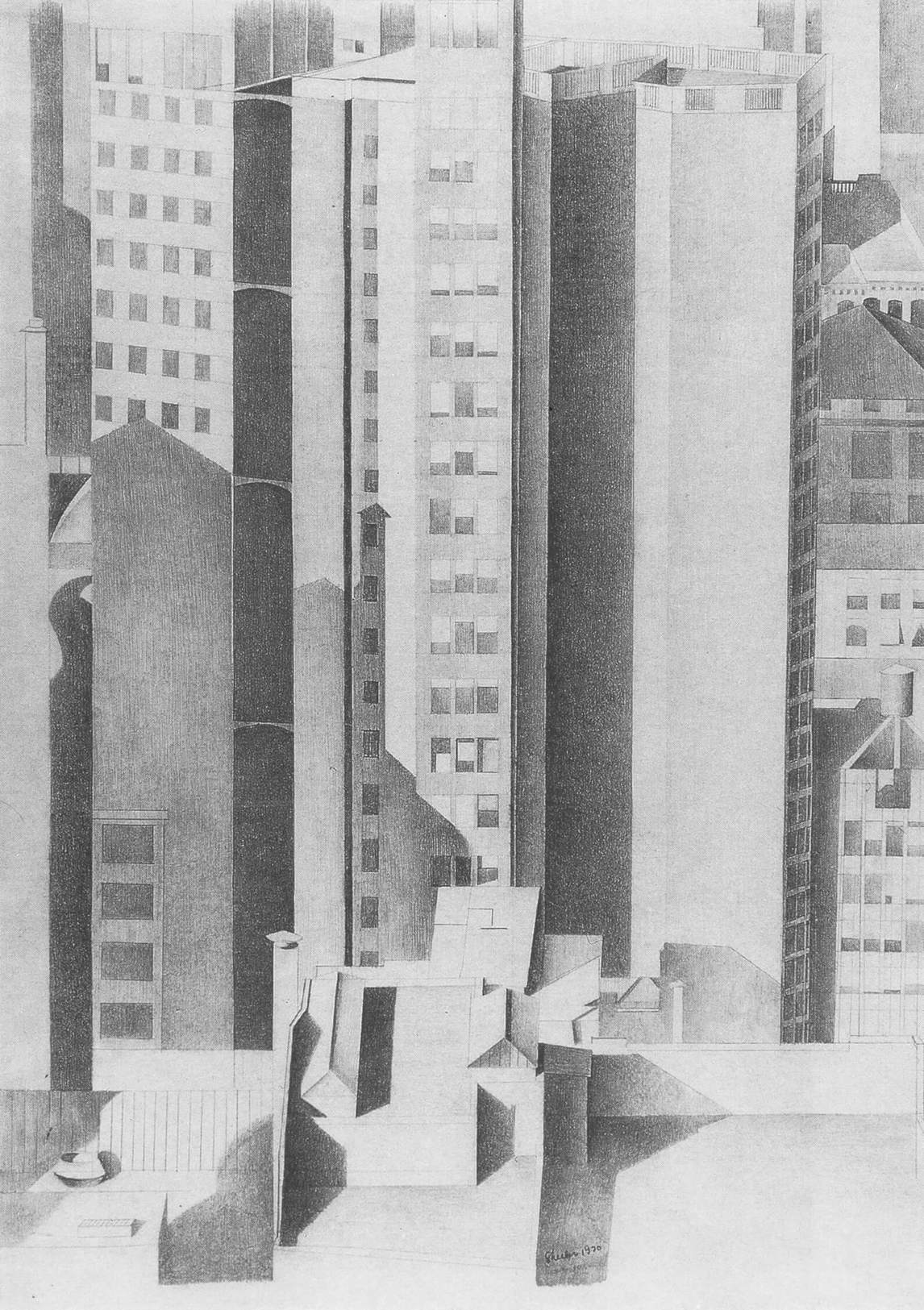

Railway Station, c. 1931–32, signals FitzGerald’s exceptional level of proficiency when sketching outdoors in lead pencil. In this example, FitzGerald employs a narrow tonal range to capture the effect of the blinding prairie light. Stylistically the drawing has affinities with the American Precisionists, a movement that came to the fore in the mid-1920s and was characterized above all by urban and industrial views conceived as precisely delineated geometric forms. FitzGerald likely first encountered the work of Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), Charles Demuth (1883–1935), and Preston Dickinson (1889–1930) in New York as early as March 1922 at an exhibition held at the Wanamaker Gallery. And later, in 1930, when visiting the Art Institute of Chicago, he recorded in his diary that Charles Sheeler’s drawing New York, 1920, struck him as “a very powerful extremely careful rendering.” FitzGerald would have appreciated how the American Precisionists used hard-edged forms to depict architectural features in terms of their structural essentials. Yet his Railway Station differs from the work of Sheeler and other Precisionists in that his forms seem to be made by human hands on a human scale rather than being giant constructions of the machine age.

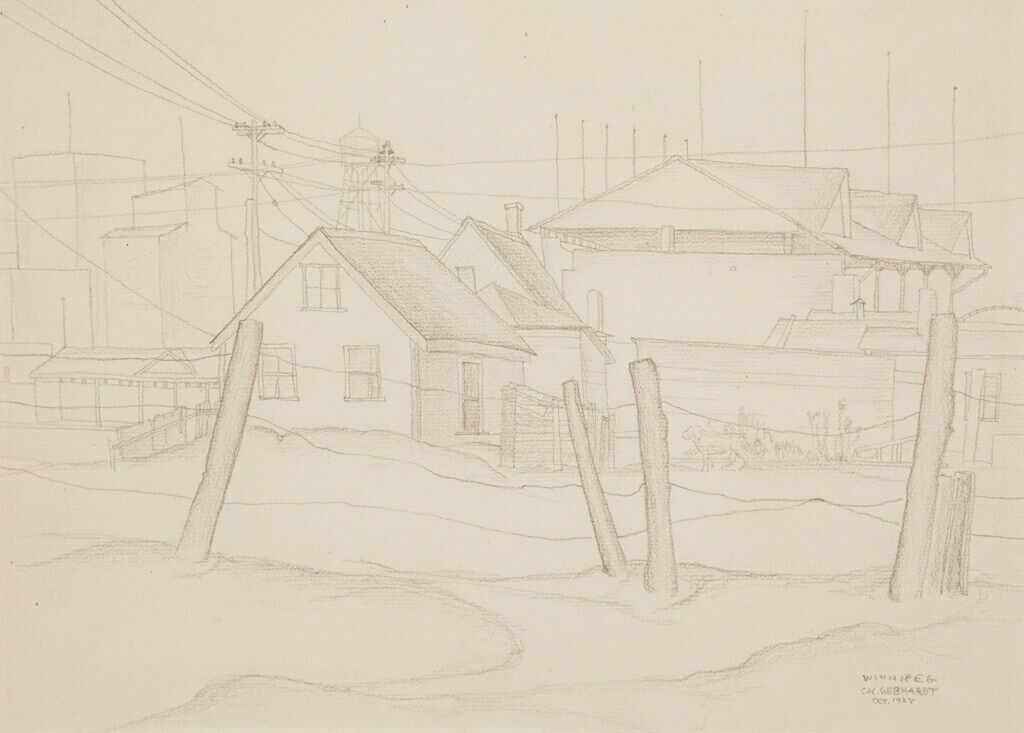

Another source of transmission of Precisionist influence came to FitzGerald via C. Keith Gebhardt (1899–1982), principal at the Winnipeg School of Art from 1924 to 1929. During this period, Gebhardt would have known about the latest developments in American art through close ties he maintained with his alma mater, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Furthermore, his background in architecture and engineering helped inform his hard-point pencil sketches, such as St. Boniface, Manitoba, 1928. While the two artists shared stylistic affinities and no doubt spoke to each other about Precisionism, FitzGerald was the more advanced due to his innate talent to select and edit only what was needed.

Drawn to the Essence

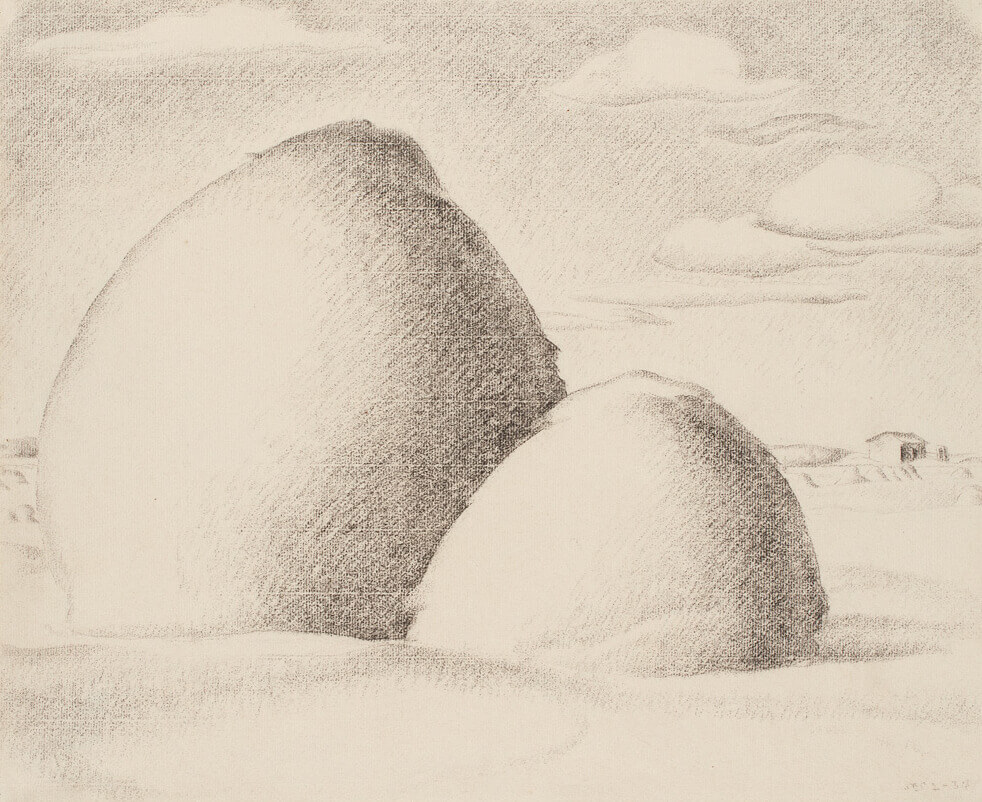

Drawing was ultimately the foundation for all of FitzGerald’s art, no matter what medium he chose. Even a study could assume as much importance for him as a finished work of art. One of his favourite activities was to sketch and paint outdoors in all kinds of weather. He is known to have fabricated a little hut on sled runners, warmed by a stove, so that he could work outside in winter when the temperature dropped well below zero (see Williamson’s Garage, 1927, and Doc Snyder’s House, 1931). And during the blistering heat of summer, FitzGerald would sit on the prairie exposed to the elements, except for the shade of an umbrella and sun visor. This was recorded in a photo documenting him at work on the drawing Haystacks, 1934, executed in charcoal on a sheet of laid paper. This type of textured support is ideal to enhance a transition from very light to intense dark tones that the medium of charcoal offers in particular.

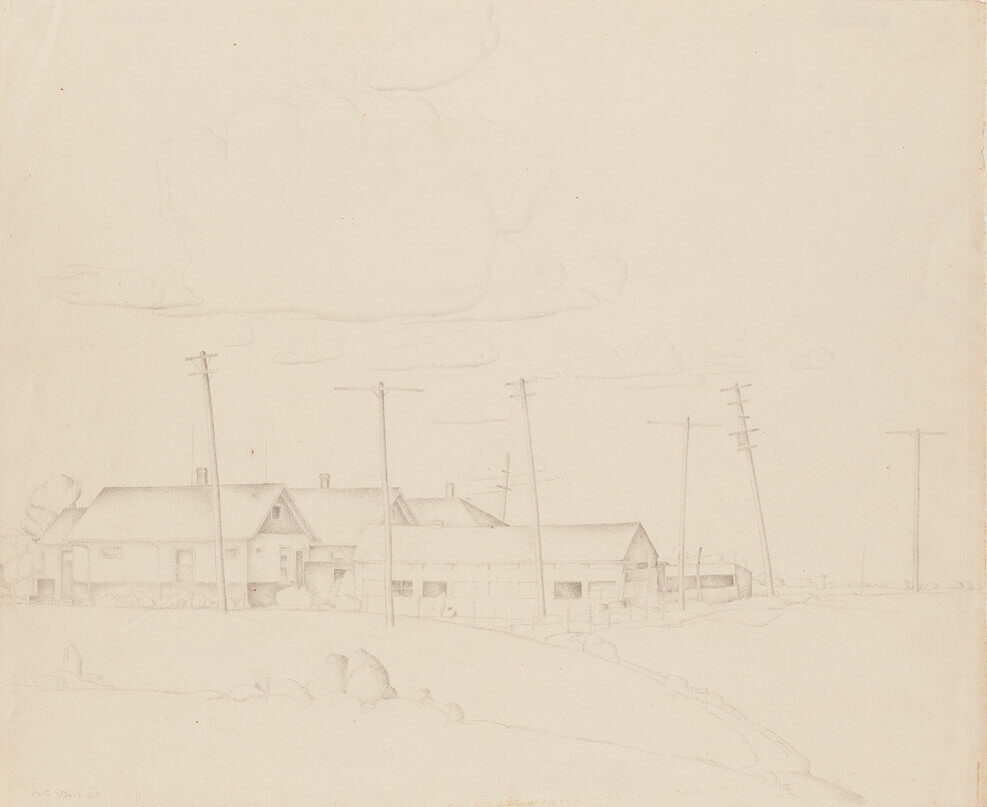

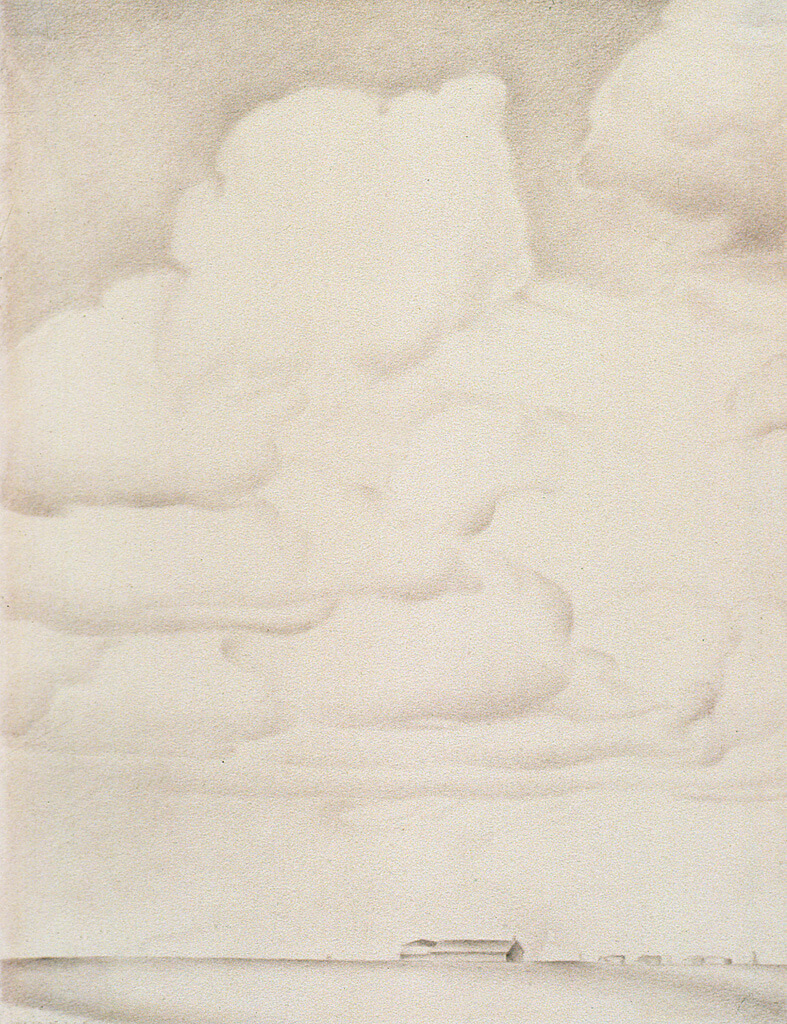

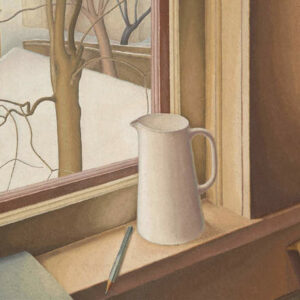

FitzGerald also used graphite, perhaps his favourite medium, to capture the outdoor prairie sky and penetrating brilliant light. The even pencil work of Prairie Landscape, June 27, 1935, where mark-making on the smooth wove paper is kept to a minimum (like oil paintings without brush strokes), helps convey the uniform envelope of light that often occurs on a sundrenched prairie day. “The only way I can account for the extreme delicacy of the pencil drawings is because of the terrific light we have here. The drawings always look strong enough when I am working on them outside, otherwise I would not be able to do them but when I get them home they have the feeling of having faded on the short trip.” For a more dynamic effect with a similar subject, FitzGerald turned to watercolour in Manitoba Landscape, 1941. Lively brush strokes describe the turbulent clouds that dominate the composition and suggest that prairie weather is powerful and ever-changing.

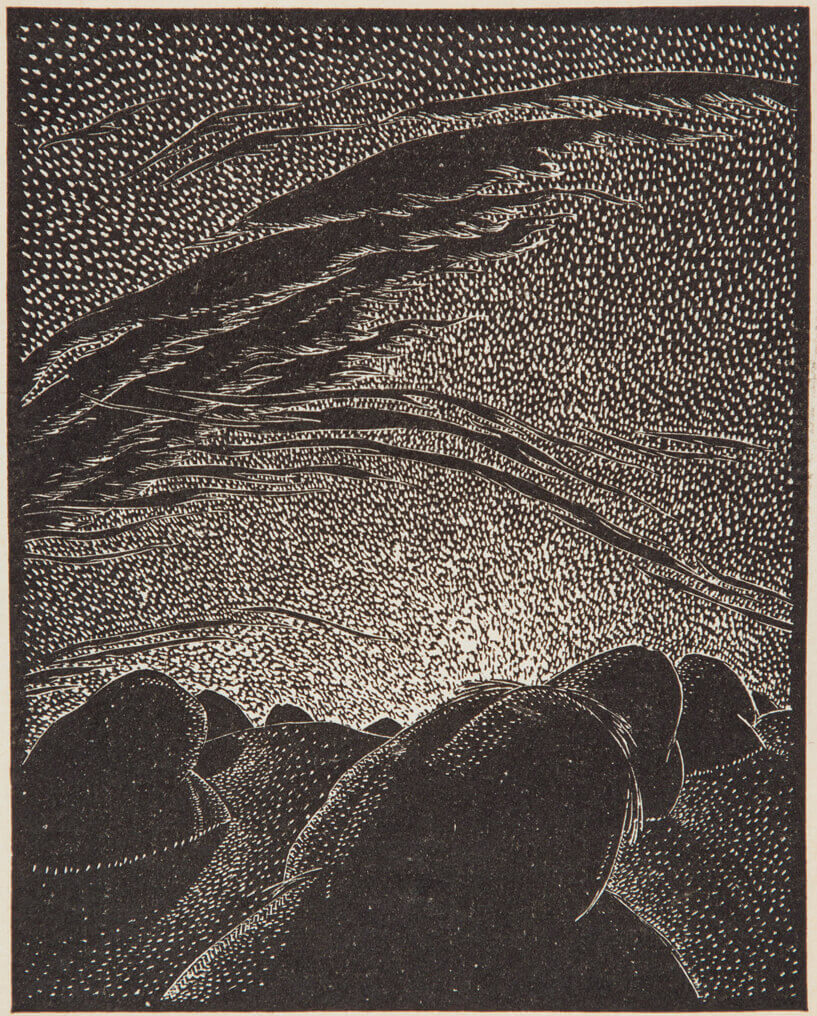

In addition to watercolours and drawings, FitzGerald found that he could also get unusual lighting effects from linocut prints. Harvest Season, c. 1935, was made by cutting flecks from a linoleum block with a sharp tool and then printing the matrix with a rich black ink. The dramatic, glowing night sky and animated stooks of wheat assume a living quality in nature that FitzGerald continued to explore in his later abstract work.

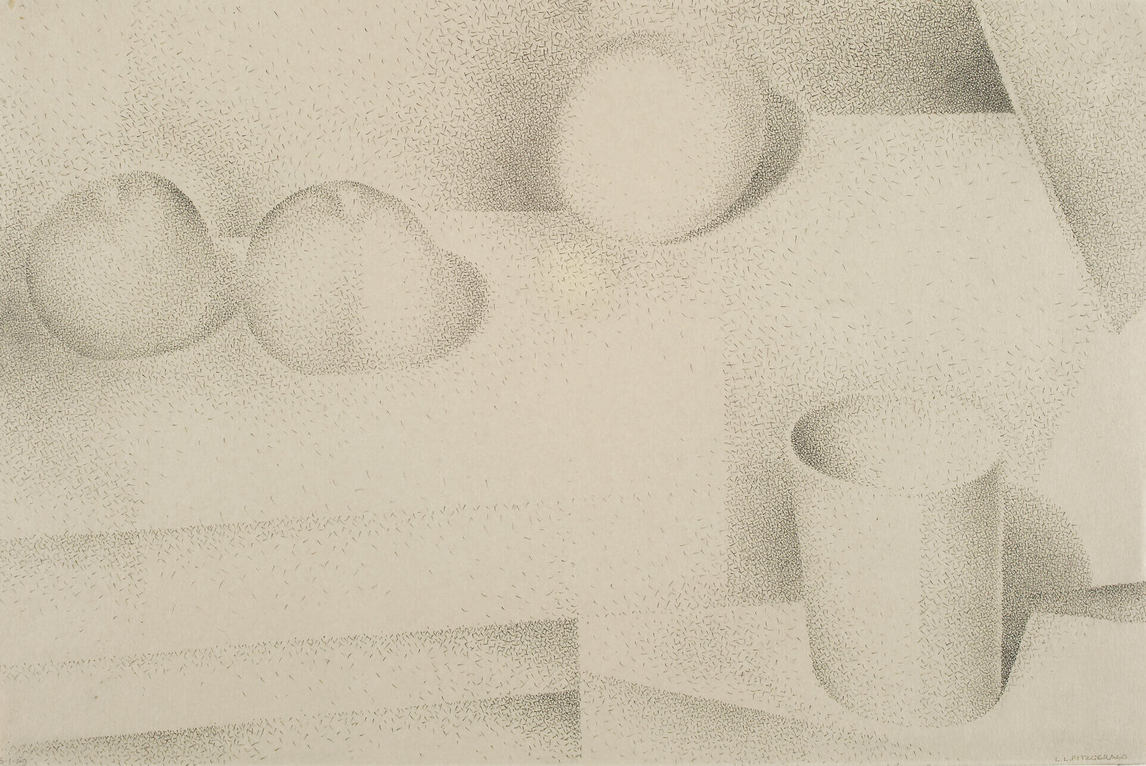

FitzGerald would often draw a still life in one medium and then recast it in another to explore different formal possibilities. In a picture like Still Life: Two Apples, c. 1940, he applied paint in small rectilinear slabs with ridged edges that combine the constructive strokes of Paul Cézanne and Augustus Vincent Tack (1870–1949) with the pointillist method of Georges Seurat (1859–1891). This technique allowed FitzGerald to create subtle transitions of light to impart solidity and volume to the apples. In the later 1940s, he found that dots and short cross-strokes in graphite, pen, coloured chalks, and watercolour could create similar effects, such as in Green Cup and Three Apples, 1949. Like Cézanne, he searched endlessly for ways to render the solidity of objects in relationship to each other through volume, space, and, most importantly, light.

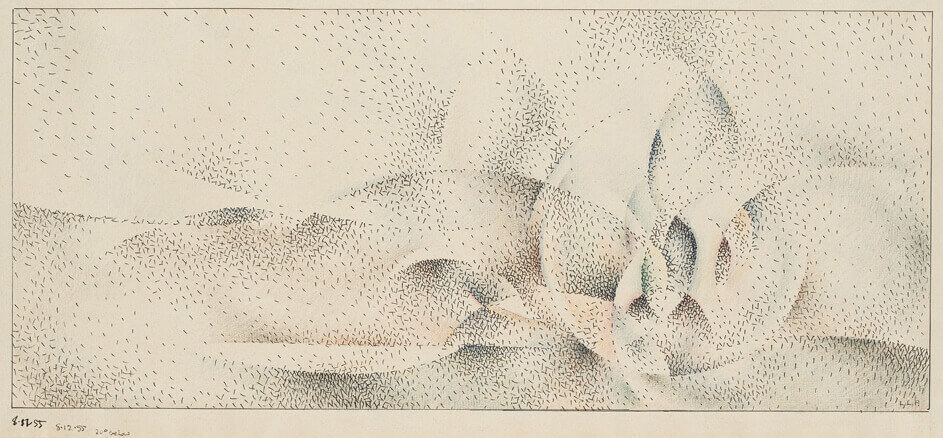

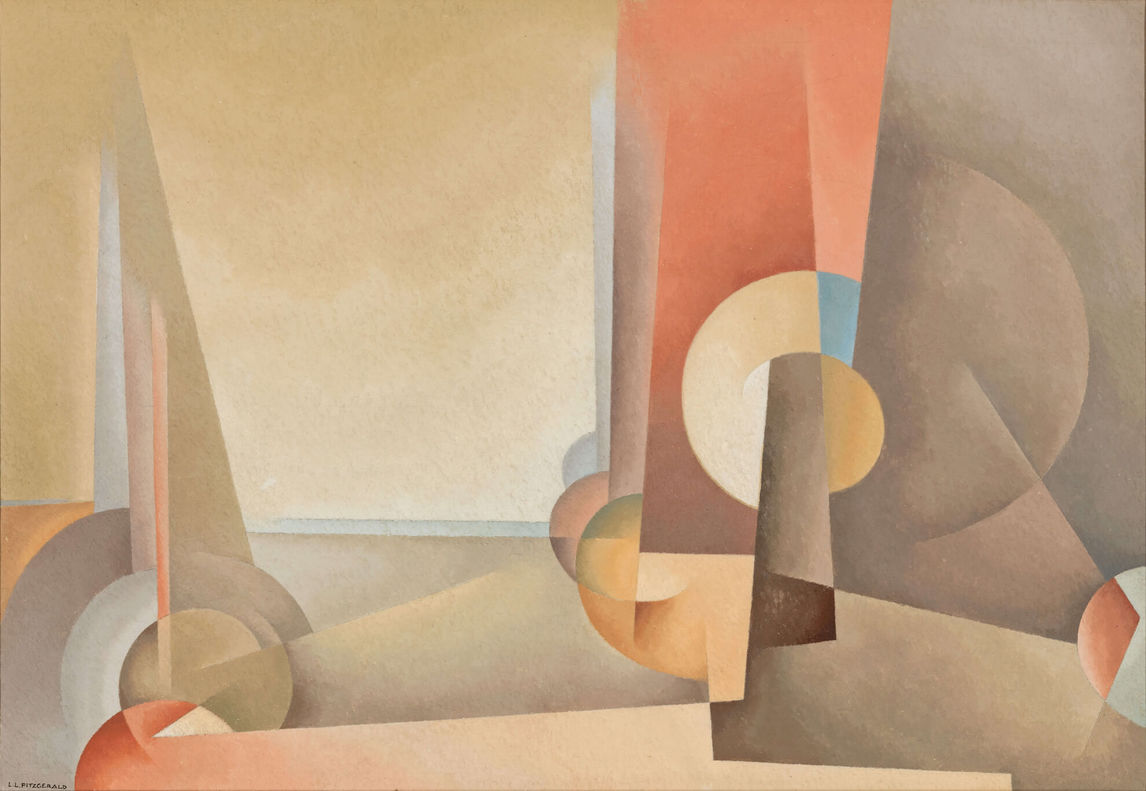

Ultimately the dot-and-stroke technique, if divorced from specific objects, could take on a life of its own. The pen-and-ink Abstract, 1955, is inscribed “20° below,” suggesting that FitzGerald continued to work outdoors en plein air to make this abstract evocation of landscape and still life. This approach led eventually to works during the 1950s in which a specific subject matter is no longer identifiable. “I am now using this accumulated knowledge [of natural forms] in some paintings of an abstract nature where I can give more reign [sic] to the imagination freed from the insistence of objects seen, using colors and shapes without reference to natural forms. It calls for a very fine balance throughout the picture requiring many preliminary drawings and color schemes, before beginning the final design.” In the late paintings of this type, such as Abstract in Blue and Gold, 1954, FitzGerald employed miniscule brush strokes to achieve subtle transitions of tone and colour between various zones.

FitzGerald clearly enjoyed the physical effort of making art, whether outdoors, in the studio, or at home. Shortly after his death, a visitor to his home observed numerous items carved or fabricated by FitzGerald, including a wooden gateway, a triangular pool with coloured tiles, a stone carving, a coloured bas-relief of two female figures, as well as “carved latches, door-knobs, etc. [which he made] as presents for friends or adornments for his own house.” These carvings represent the private world of FitzGerald, who was not afraid to create in any media at hand. A 1936 photograph documents the artist carving a sculpture in oak that appears to represent a female figure morphing into a plant and melding with a tree trunk. FitzGerald’s willingness to experiment in wood in order to explore this type of anthropomorphism is a prime example of his choice of a medium closely aligning with meaning.

Thus a technique such as carving and a medium such as wood were simply vehicles used by FitzGerald in his continual search to find the best means to communicate as an artist. How he worked on canvas, paper, or any other medium came with his warning that technique is only the handmaiden to meaning: “Consider technique as a means by which you say what you have to say and not as an end in itself. What you have to say is of the first importance; how you say it is always secondary.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements