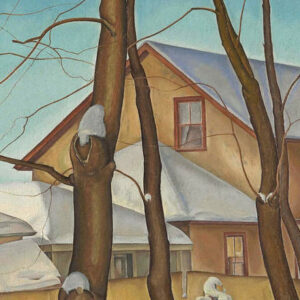

The Little Plant 1947

Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald, The Little Plant, 1947

Oil on canvas, 60.5 x 45.7 cm

McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario

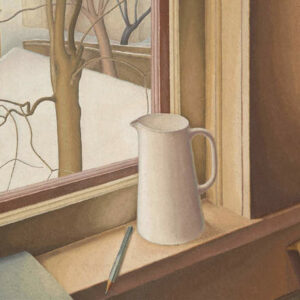

FitzGerald’s idea to take as a subject a begonia sitting on a windowsill with a view to the wooded backyard behind his house may have derived from a 1943 photograph. The Little Plant combines elements of both still life and landscape in a single picture—a strategy the artist pursued in particular from around this time (Four Apples on Tablecloth, December 17, 1947) to the early 1950s (From an Upstairs Window, Winter, 1950). With its harmonious balance of realism and abstraction as well as beautiful colour and design elements, The Little Plant may be considered one of FitzGerald’s greatest achievements in paint. Here, the exuberant growth of the flowering plant indoors is counterpoint to the animated energy of the thick screen of trees outside.

FitzGerald applies paint with a palette knife so that the entire surface appears like a ridged mosaic. This is reminiscent of the way that Augustus Vincent Tack (1870–1949), many years earlier, painted his murals in the Manitoba Legislative Building, Winnipeg. The technique might also have been derived, as Helen Coy, former curator of the FitzGerald Study Collection at the University of Manitoba, has suggested, from A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884, 1884/86, by Georges Seurat (1859–1891), which FitzGerald saw at the Art Institute of Chicago during his 1930 trip to the United States.

The Little Plant was begun in 1946 for FitzGerald’s longtime friend Arnold Brigden (1886–1972) and finished by the spring of 1947. Since he worked directly from nature, FitzGerald would have had to put The Little Plant aside in the spring of 1946 due to the change of seasons, when the background trees would have been coming into leaf rather than denuded as he painted them. He then finished the picture the following year. While he complained of frustration at not being able to create works of art on a full-time basis, FitzGerald often struggled with painting, a medium that was so much more demanding for him than drawing, in part due to the time element involved.

FitzGerald’s greatest concern was to express a unity in all the elements of the picture so that indoors and outdoors were joined together as one living entity. By wresting a rhythmic geometry from the tangle of nature, FitzGerald creates a world at once more animated and more tranquil than what appeared before his eyes. Perhaps it was this dream-like coexistence of movement and stillness that made this painting the favourite of his daughter, Patricia.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements