Abstract Landscape 1942

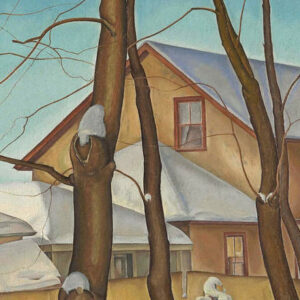

Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald, Abstract Landscape, 1942

Coloured chalks on wove paper, 61 x 46 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

The summer of 1942 was a particularly creative time in FitzGerald’s career. Visiting British Columbia’s West Coast for the first time, he stayed at his daughter’s cottage on Bowen Island. There, the new environment, so different from Manitoba, proved to be a tremendous visual stimulus for the artist.

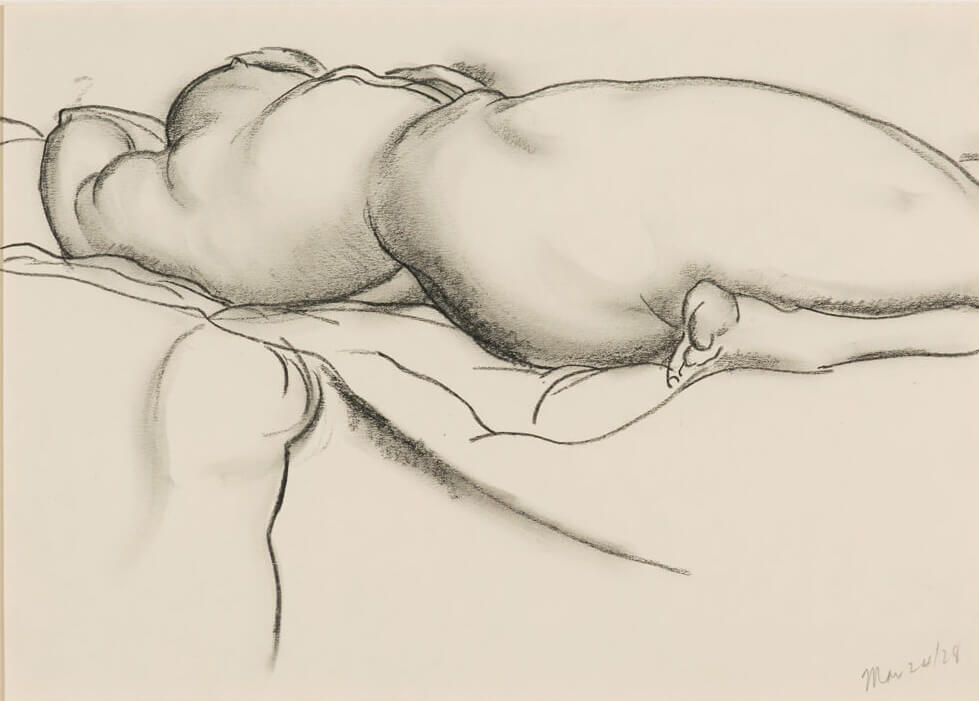

Abstract Landscape is one of the earliest drawings in which FitzGerald builds forms using masses of short-flecked strokes of coloured chalks. This technique, where mark-making does not necessarily describe an identifiable subject, was to inform his work at times for the rest of his career. Abstract Landscape is a challenge to read given the shallow space and climbing perspective of cropped and jumbled forms that may represent a rock face with a tree in the foreground. The tree that dominates the picture from left to right and the diagonal rock element just behind it on the right suggest affinities with parts of the human body. These similarities can be seen in an earlier drawing, Nude Reclining on Bed, 1928.

FitzGerald described his anthropomorphic approach to nature in a 1937 letter to Bertram Brooker (1888–1955): “The seeing of a tree, a cloud, an earth form always gives me a greater feeling of life than the human body. I really sense the life in the former, and only occasionally in the latter. I rarely feel so free in social intercourse with humans as I always feel with trees.”1

As art historian Brian Foss has observed: “The depiction of natural phenomena—the meticulous capturing of ephemeral tonal gradations and minute details—was not an end in itself, but rather a gateway leading to the potential discovery of the underlying oneness of all things.”2 FitzGerald viewed nature as living, growing, and never static, and so his willingness to invest inert forms with a life of their own is in keeping with his concept of the universe. Back in Winnipeg in September of 1942, he summed up his experience of the past summer: “I was just becoming aware of the possibilities of the material and getting a sense of power that I don’t remember ever being so strong. Two or three of the last things contained a living quality that was tantalizing…. I felt them so much of myself.”3

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements