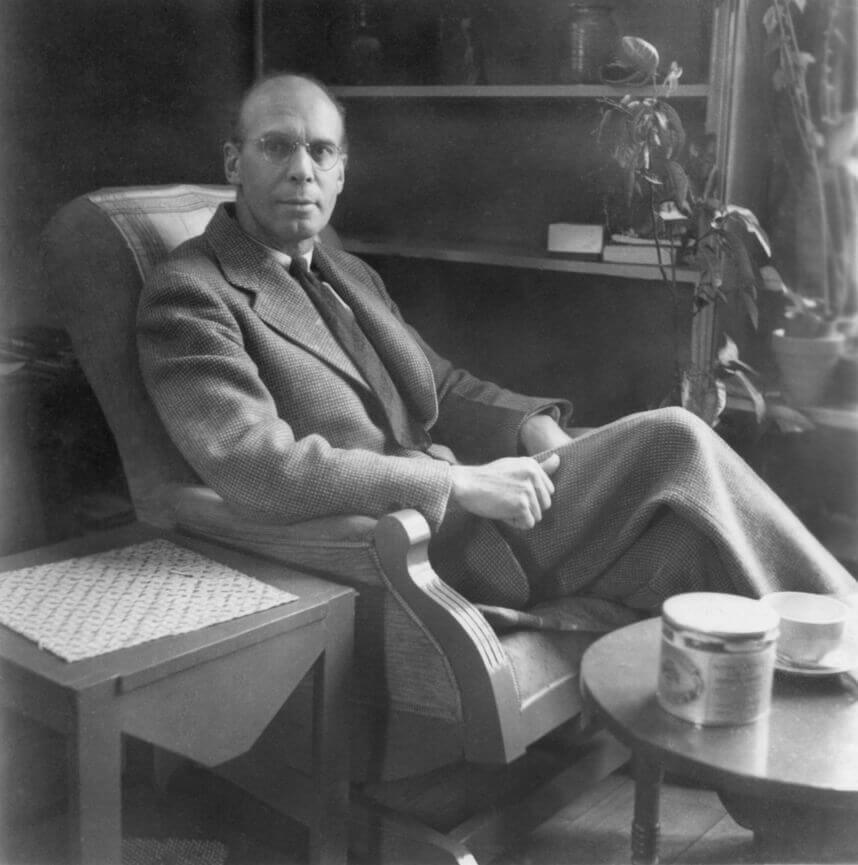

Rooted in his native city of Winnipeg, Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) worked almost exclusively in Manitoba, where he captured the essence of the prairie in his art. Although he accepted the Group of Seven’s invitation to become a member in 1932, FitzGerald was less concerned than the group was to promote issues of Canadian identity. Instead he explored his surroundings, delving deeply into the forces he felt animated and united nature in order to make “the picture a living thing.” Quiet in personality and passionate about art, FitzGerald inspired a generation of students at the Winnipeg School of Art.

Early Years

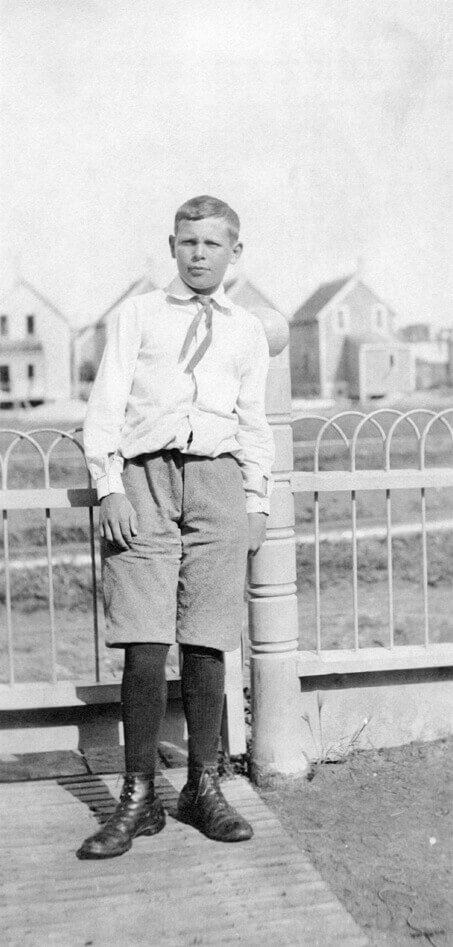

Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald was born March 17, 1890, in Winnipeg, Manitoba. While this prairie location is central to understanding his artistic universe, FitzGerald’s family roots were in Eastern Canada. His father, Lionel Henry FitzGerald (1864–1943), was raised by relatives in Quebec City with the surname Le Moine. In recognition of their kindness, Lionel Henry gave his eldest child their name as well as his own.

In 1888 Lionel Henry FitzGerald married Belle Hicks (1864–1940), who at age sixteen had moved with her family from Ontario to the southern Manitoba farming community of Snowflake. LeMoine FitzGerald’s parents often took him, his brother, Jack (b. 1893), and his sister, Geraldine (b. 1896), to the Hicks’s family farm. These visits would play a crucial role in the development of his relationship with nature. “Summers spent at my grandmother’s farm in southern Manitoba were wonderful times for roaming through the woods and over the fields and the vivid impressions of those holidays inspired many drawings and paintings of a later date.”

Winnipeg at the turn of the century was a burgeoning centre of Western Canadian commerce and agriculture, but it was still culturally isolated, having neither a public art gallery nor an art school—although the Winnipeg Theatre, which seated one thousand people, had opened in 1897. New initiatives in the visual arts, however, were beginning, with the founding of the Winnipeg branch of the Women’s Art Association of Canada in 1894 and the Manitoba Society of Artists in 1902.

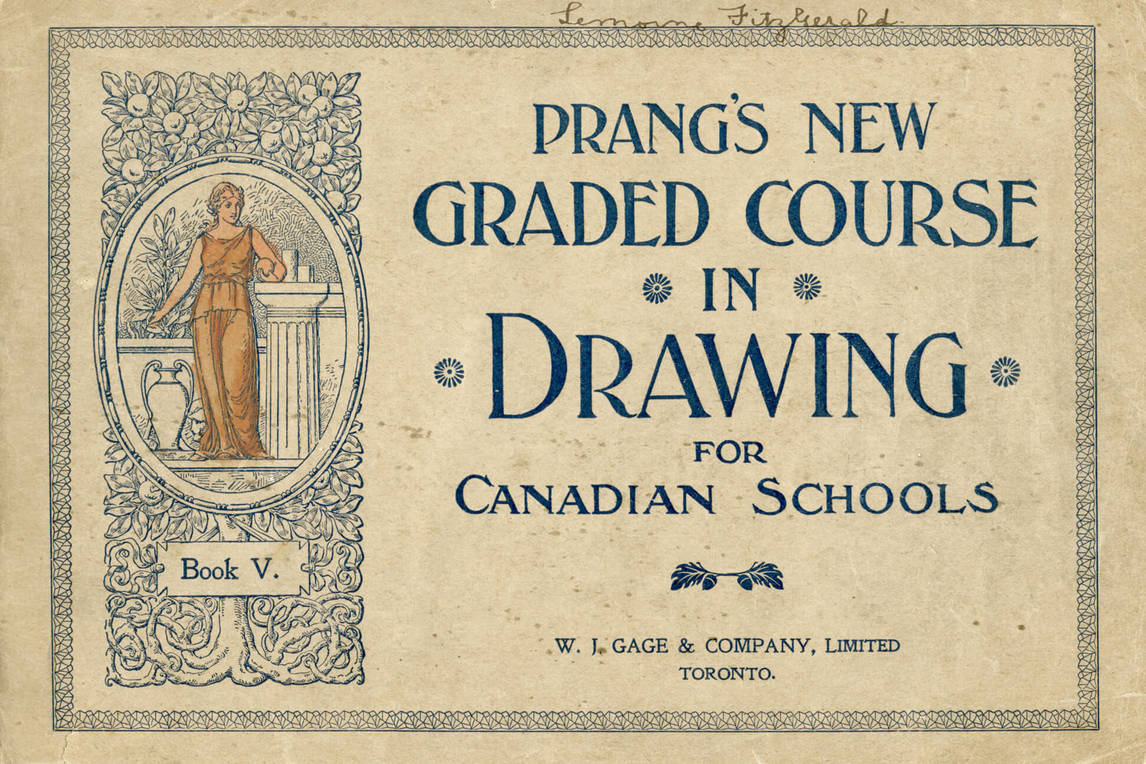

FitzGerald’s grade three teacher introduced him to Perry Pictures, reproductions of art masterpieces. In grade seven, at Somerset School, he enjoyed drawing lessons from a popular exercise book, Prang’s New Graded Course in Drawing for Canadian Schools. Based on interviews and conversations, art critic Robert Ayre imagined FitzGerald to be a “dreamy” child who loved to “watch the earth, not to study it as geology or botany, not to classify it, but to look at it, to soak it in, to experience it, to make the earth’s life part of himself.”

Artistic Formation

In 1904 fourteen-year-old FitzGerald graduated from grade eight at Victoria Public School and worked for the next two years as an office boy in the pharmaceutical company Martin, Bole and Wynne. Between 1907 and 1908 he was a junior clerk with the real estate and brokerage firm Osler, Hammond and Nanton, interrupting that job with a short period in a commercial art studio before returning to the brokerage firm. A restlessness with the daily routine of office work seems to have prompted his desire to draw. “One of the first efforts, out of doors, was the drawing of a large elm tree and I remember a friend and I making great preparations and walking a long distance to find a subject that appealed to us.” This was the starting point for an artistic career that would be based almost entirely on a close observation of nature in order to understand the underlying dynamic forces that FitzGerald felt animated all living things.

When the Winnipeg Public Library (then called the Carnegie Library) opened on William Street in 1905, new vistas opened for the precocious teenager. FitzGerald later remembered “strange books I read at that time trying to find out something about art.” The writings of the British artist and art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) were a formative influence and guided FitzGerald’s thinking about how a beginner could get started making art. FitzGerald practised drawing lessons suggested by Ruskin and pored over reproductions of paintings by John Constable (1776–1837) and J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), whom he considered “something of a god.” Watercolours by Richard Parkes Bonington (1802–1828) reproduced in The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine & Applied Art were of such fascination that the sixteen-year-old FitzGerald was compelled in 1906 to make a watercolour copy of A Street in Rouen.

The next step in FitzGerald’s art education was instruction from a trained artist. In March 1909 he enrolled in classes given by the Hungarian painter Alexander Samuel Keszthelyi (1874–1953), who had arrived in Winnipeg via Munich, Vienna, and the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A.S. Keszthelyi’s School of Fine Arts gave instruction in “Drawing and Painting from the living model, Decorating, Designing and Portraiture.” FitzGerald loved it. “The whole winter was a marvelous experience. I am still wondering how it was possible to find out so much in so short a time.”

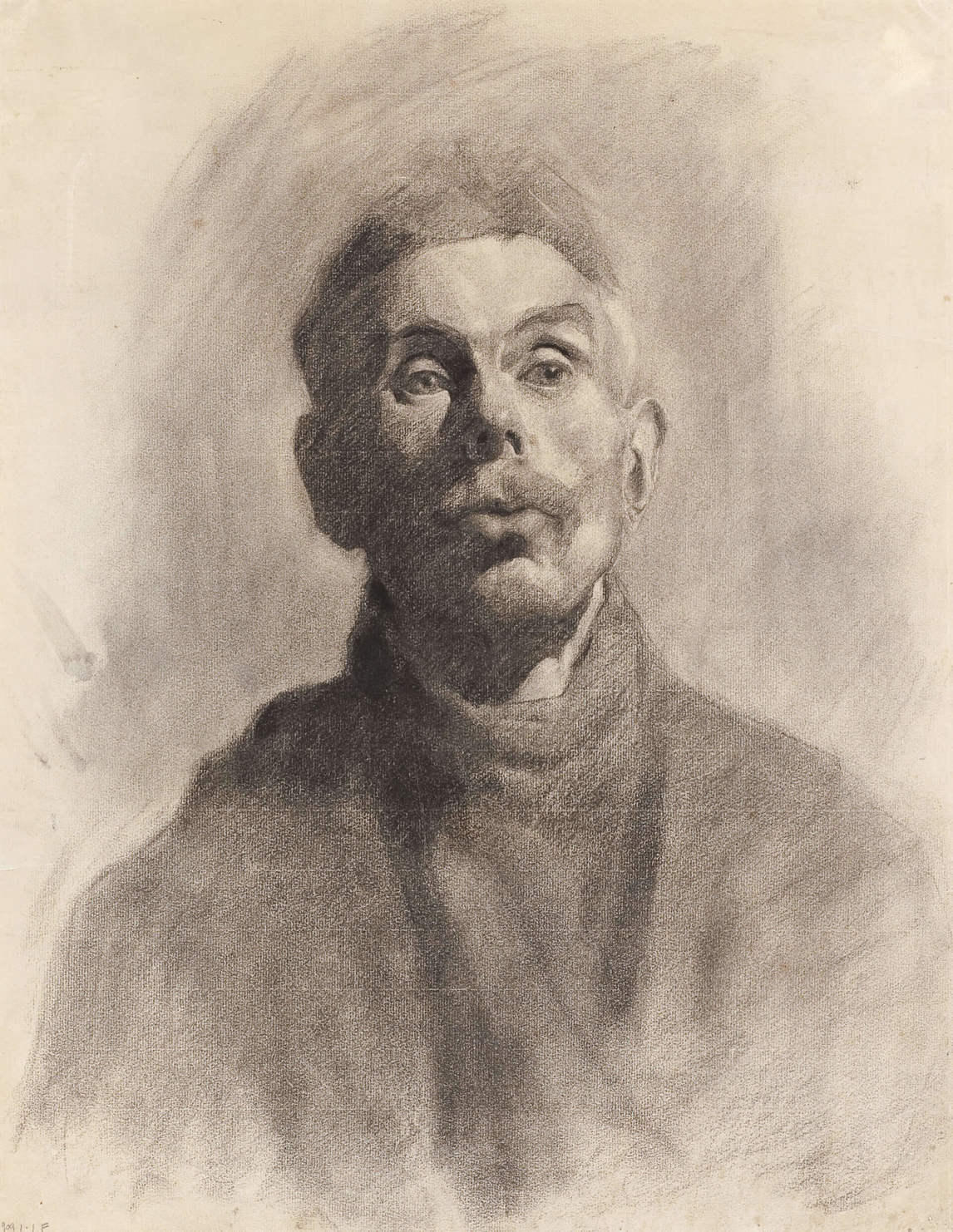

FitzGerald’s budding talent as a draftsman is seen in two 1909 charcoal drawings, Seated Man and Bust of a Man, believed to date from the life class at Keszthelyi’s school. Since drawing was the real foundation of FitzGerald’s artistic career, no matter what media he chose, his early training from life and still life allowed him to move forward as an artist.

Early Influences

The year 1912 proved to be a major turning point in FitzGerald’s life. In late November he eloped with Felicia (Vally) Wright (1883 or 84–1962), six years his senior, to avoid any interference from his parents. Vally was a trained soprano who made her living by teaching singing lessons and performing in church choirs. Employment opportunities for budding Canadian artists were limited, and around the time of his marriage FitzGerald began to work in the art department of an advertising firm in Winnipeg.

FitzGerald’s start in advertising was “the beginning of nine years spent in a wide variety of work, including advertising drawings, mural paintings and sketches for interior decorations, posters and window backgrounds, stage scenery, lettering and so on. As well as giving me a great deal of valuable experience, it was a congenial means to a livelihood.” Certainly the demands of commercial enterprise forced him to use a wide variety of media, but what was beginning to thrill FitzGerald most was working with oil paint. His response to the paraphernalia of painting was visceral. He recalled how excited he was to smell the oil, mix the colours on his palette, and use a brush, which felt so clumsy by comparison to the sharpness of a pencil. While he still worked in pencil and watercolour, oil paintings of landscape subjects began to dominate his work.

At the beginning of the First World War, FitzGerald’s viewing experience would have been informed primarily by Barbizon and Hague School pictures, both extremely conservative and popular types of nineteenth-century European landscape painting. His knowledge of such works probably occurred in 1910 during a brief stay in Chicago, where he likely visited the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1912 FitzGerald shared a studio with artist Donald Macquarrie (1872–after 1934), the first curator (December 1912–March 1913) at the fledgling Winnipeg Museum of Fine Arts (now the Winnipeg Art Gallery) and FitzGerald’s sketching companion during that summer. Macquarrie’s aesthetic predilection for the Barbizon artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) may have influenced a series of small monoprints of urban and landscape scenes that FitzGerald made in 1914.

But FitzGerald was also beginning to try his hand at Impressionism. He was now working sometimes en plein air, perhaps encouraged by his friend the Winnipeg painter Mary Ewart (née Clay) (1872–1939), who had studied in the 1890s with the American Impressionist William Merritt Chase (1849–1916). Nonetheless, FitzGerald’s knowledge of French Impressionism would have been second-hand, through his study of the black and white reproductions in The Studio magazine and its American counterpart, The International Studio, or mediated by a few paintings by Canadian Impressionist artists in Royal Canadian Academy of Arts or Ontario Society of Artists touring exhibitions. Reflections, 1915, is an early attempt at an Impressionist treatment of dappled light effects on water that suggests FitzGerald was aware of similar subjects, such as Railroad Bridge, Argenteuil, 1874, by the great master of French Impressionism Claude Monet (1840–1926). In 1918 FitzGerald sold an Impressionist-inspired painting, Late Fall, Manitoba, 1917, to the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. His understanding of Impressionism developed rapidly, and two vibrantly coloured paintings—Summer, East Kildonan, 1920, and Summer Afternoon, The Prairie, 1921—mark the high point of his early career.

New Directions

The advent of the 1920s signalled changes in FitzGerald’s artistic direction. The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, a response to skyrocketing increases in the cost of living and extremely low wages, illustrates the uncertainty of the times. Even so in January 1920 FitzGerald found employment with the American artist Augustus Vincent Tack (1870–1949), who had been commissioned to execute a mural in Manitoba’s Legislative Building in Winnipeg. The two worked together until the allegory was completed in July 1920. FitzGerald learned from Tack that drawing should be the underlying armature on which to build a painting, and in the 1940s FitzGerald sometimes adopted Tack’s technique of using small, overlapping, rectilinear slabs of colour.

Tack’s commission brought attention to FitzGerald in the local Winnipeg art scene and helped secure his first one-man exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1921. The show was a commercial and critical success: eighteen works were sold, including the most expensive, Summer Afternoon, The Prairie, 1921, which was bought by the Art Gallery Committee of the Winnipeg Museum of Fine Arts for $300. Literary critic and editor William Arthur Deacon wrote an enthusiastic review, concluding: “Winnipeg is going to be very proud that Mr. FitzGerald was born here, and should be so already.”

In November 1921 FitzGerald moved to New York to attend art school while Vally relocated near Montreal with their young children, Edward (b. 1916) and Patricia (b. 1919). Vally gained employment at a tea house/inn called The Rip Van Winkle while LeMoine took courses at the Art Students League of New York from December 1921 to the end of March 1922. The Canadian-born artist Boardman Robinson (1876–1952) taught him “Drawing and Pictorial Design” and Kenneth Hayes Miller (1876–1952) instructed him in “Life Drawing and Painting for Men.” Both Robinson and Miller were competent traditional figure painters who would have helped FitzGerald hone his skills in the drawing studio. However, his exposure to modern painting would have come from conversations with fellow students and visits to local museums and commercial galleries, such as the Wanamaker Gallery, where he would have seen the work of the American Precisionists in March 1922. This experience likely contributed to his later remark to art critic Robert Ayre that he got “a sudden jolt into everything.”

Modernism in Isolation

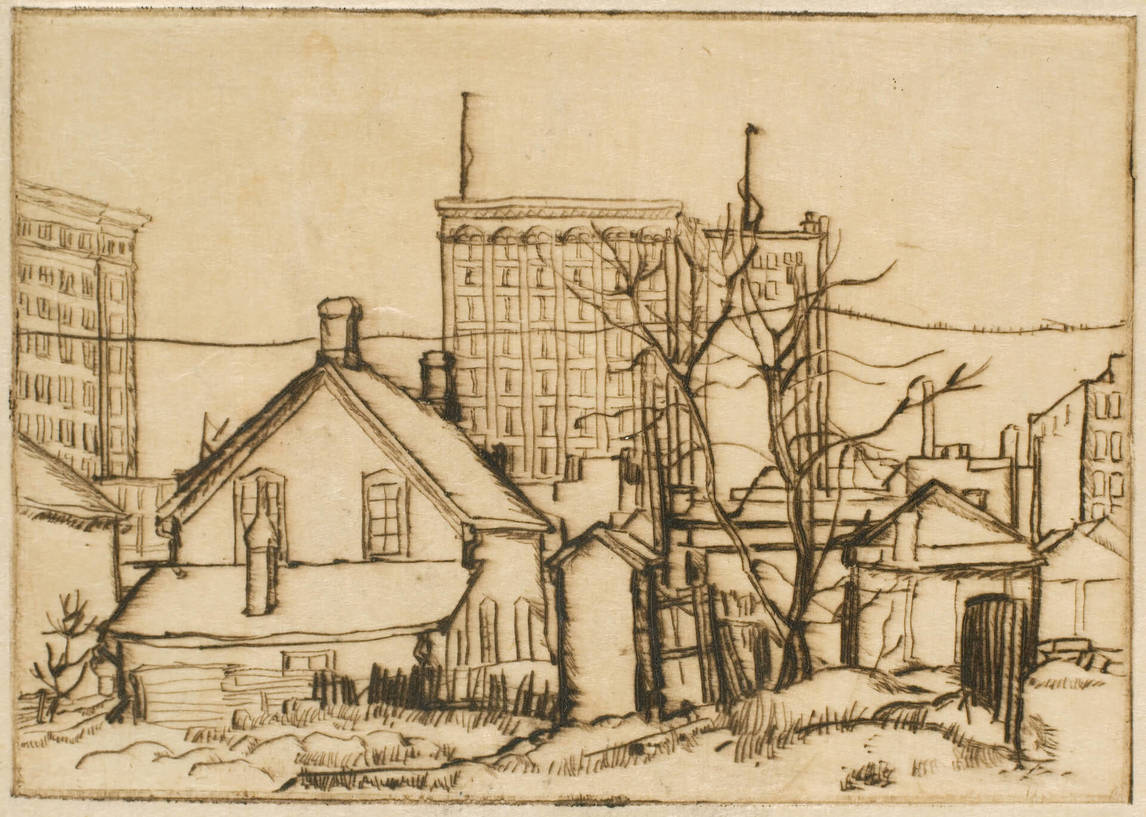

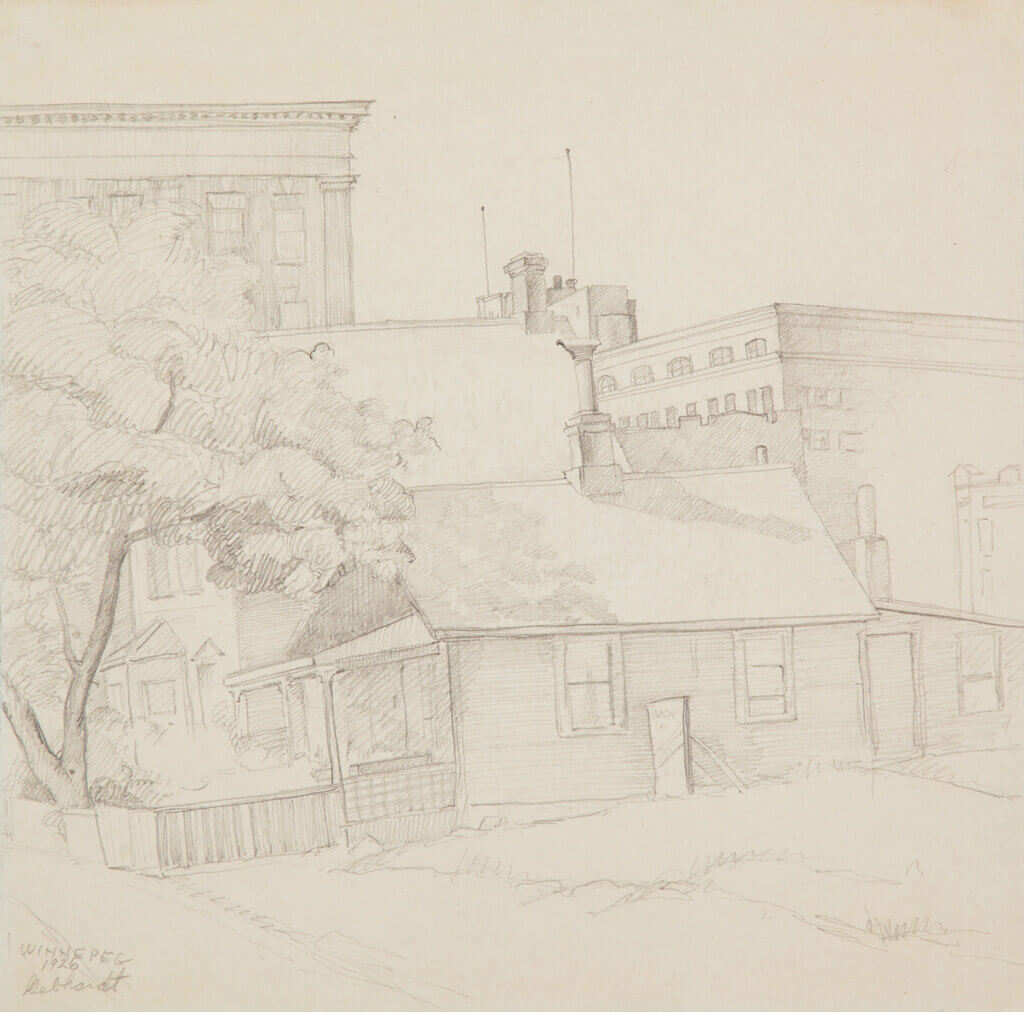

Back in Winnipeg in 1924, FitzGerald was offered a position teaching design, drawing from plaster casts after classical antiquity, and still life at the Winnipeg School of Art. C. Keith Gebhardt (1899–1982), an American who had taught in the summer program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, was principal. The two men forged a deep friendship built on mutual admiration and an intense devotion to drawing. Gebhardt’s delicate pencil studies of local landscape and urban scenes were to inspire FitzGerald to delve even more deeply into drawing as the medium he most preferred. For a few years, he concentrated primarily on drawing in pen and pencil while he searched for ways to consolidate what he had learned in New York. Printmaking in drypoint (for example, Old House and Buildings, 1923), and later linocut, proved to be important additions to his technical arsenal. He continued to do commercial work and also designed sets for the Community Players of Winnipeg, a local theatre group.

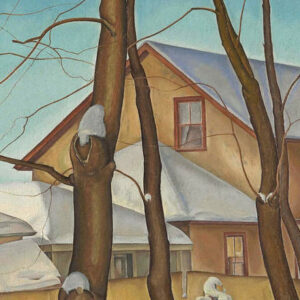

By 1927 FitzGerald had returned to painting with the small but significant Williamson’s Garage, 1927. In many ways this picture is the quintessential example of the artist’s belief that suitable subjects for painting might be found in one’s backyard. This modest winter scene anticipates by a year what might be termed the first major picture of FitzGerald’s career, Pritchard’s Fence, c. 1928. These paintings are characterized by a precise harmony of drawing and painting that would mark his mature style and secure his reputation within the Canadian art world.

Keith Gebhardt wrote: “Winnipeg during my residence was pretty dull artistically.” While isolation could have been a weakness, it had the virtue of allowing FitzGerald to develop his own artistic theories independent from others. By the time he met Toronto artist Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) in Winnipeg in July 1929, FitzGerald’s ideas were fully formed, although he took every opportunity to discuss art with this lively and astute colleague. Brooker was a link to the activities of the Group of Seven and the larger art scene in Eastern Canada. The two artists enjoyed a deep friendship, apparent in their extensive correspondence marked by FitzGerald’s elegant handwritten letters and Brooker’s typewritten, single-spaced, multi-page missives.

FitzGerald had admired the paintings and activities of the Group of Seven from a distance and knew group member Frank H. Johnston (1888–1949), who was principal at the Winnipeg School of Art from 1921 to 1924. By the late 1920s the group was taking notice of FitzGerald. Lawren Harris (1885–1970) in particular expressed enthusiasm for FitzGerald’s drawings and initiated correspondence to share his admiration following FitzGerald’s first solo exhibition in Eastern Canada at the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto in 1928. “I particularly like the way you extricate a suggestion of celestial structure and spirit from objective nature in your drawings.” This precipitated a lifelong friendship characterized by mutual encouragement and understanding between the two artists. When they finally met in Vancouver in 1942, Harris continued to admire what he perceived to be an evocation of the mystic in FitzGerald’s work. In turn, FitzGerald wrote about Harris’s “fine sense of design, beautiful restrained colour and exquisite craftsmanship.”

Beyond Winnipeg

In 1929 FitzGerald was appointed principal of the Winnipeg School of Art. One of the first challenges he faced was the stock market crash in October of that year and the possible impact of dire economic consequences on student registration, which he addressed in a January 15, 1931, report to the board of directors. “The number of students on the roll at the present time is 296 as against 320 of last year, on the same date. Although the enrollment is a little lower than last year, the attendance in the various classes is better than usual.”

In spite of the difficult times, it was with optimism that FitzGerald viewed his first task as principal, which he felt was to seek out the latest developments in art school instruction. From June to July 1930, he visited Minneapolis, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, New York City, Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto, familiarizing himself with art galleries and education programs at a number of major North American museums. For an artist who travelled rarely, the exposure to great works of art by modern masters, such as Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Claude Monet (1840–1926), Georges Seurat (1859–1891), and particularly Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), would have a profound and lasting effect. The diary that he kept during this period records his lively response to paintings by these artists, especially those at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where five Cézanne paintings from the Havemeyer bequest impressed him for their “terrific sense of unity…. And always a great sense of reality, no matter how abstract the thing may be.”

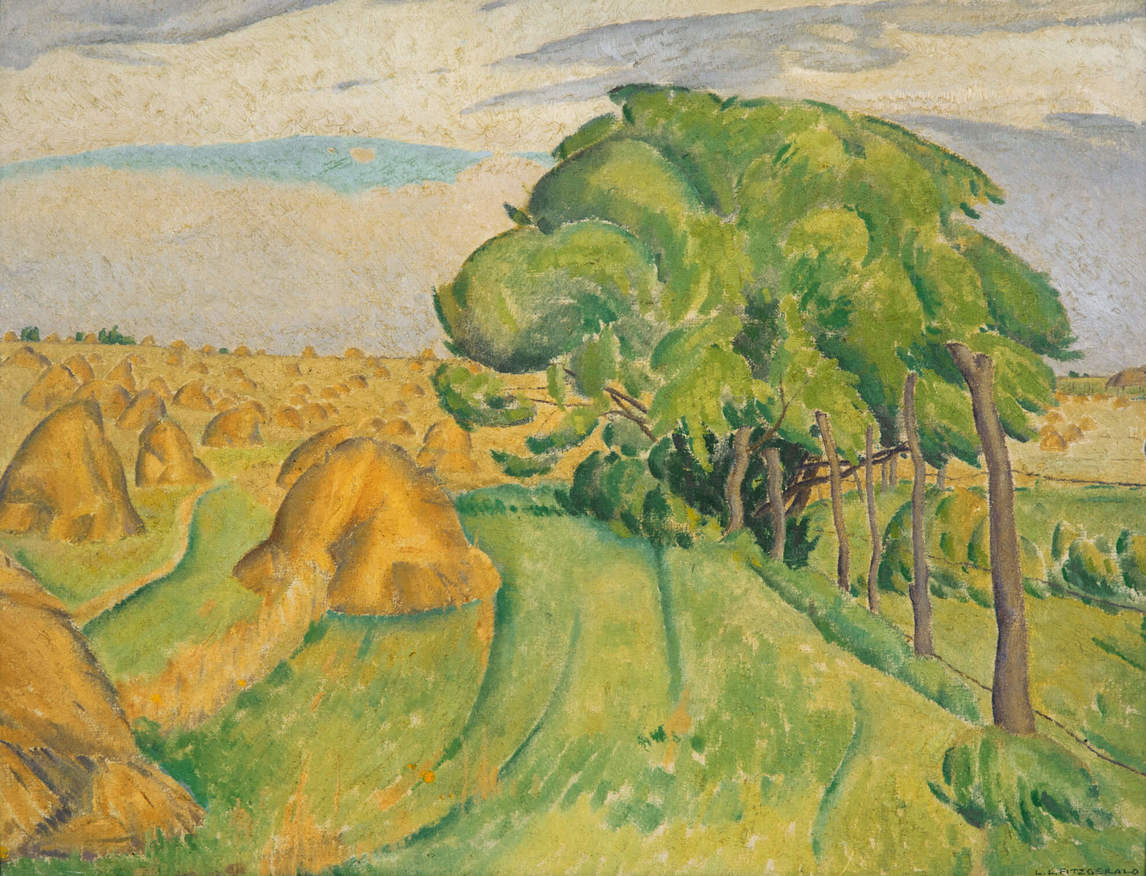

In 1930 and 1931 FitzGerald was invited to participate in Group of Seven exhibitions held at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). Untitled (Stooks and Trees), 1930, is the type of FitzGerald landscape from this period that the group would have likely admired for capturing the quintessence of the Manitoba prairie on a hot summer day. When the group decided to expand their membership in 1932, FitzGerald was their unanimous choice and the only Western Canadian artist they ever considered. FitzGerald’s acceptance made him the tenth artist to become a member since the group’s inception. Although this was a boost to his confidence, he remained removed from the group due to both geographical distance and his personal aesthetic, which did not consider the landscape primarily as a vehicle for Canadian nationalism. FitzGerald exhibited with them only once as a member before they disbanded in 1933 to reorganize as the Canadian Group of Painters, of which FitzGerald was a founding member.

For FitzGerald, the formal relationships of line, colour, and shape in a picture were fundamentally more important than subject matter. Unity, balance, and harmony were always the prime objectives of his art. In June 1931 he finally completed Doc Snyder’s House. This painting of his neighbour’s residence took substantial effort and a year and a half to complete but gave FitzGerald the satisfaction of knowing it was one of his best oil paintings. He hit his stride in his late thirties and early forties, creating at least a dozen oil paintings that are some of the finest of his career, such as Apples, Still Life, 1933, and culminating in The Pool, 1934. The abstract qualities of this picture were revisited when FitzGerald abandoned any notion of site-specific subjects in the 1950s.

A Change of Scene

The opportunity to “build another phase” occurred unexpectedly during the summer of 1942 when FitzGerald and his wife ventured beyond the familiarity of their home in Manitoba. Their daughter, Patricia, owned a cottage that they had never visited, on Bowen Island near Vancouver. While the trip was meant to be a break from his work, FitzGerald found the coastal and mountain landscapes compelling subjects for drawings that advanced his idea of the interconnectedness of all things in nature.

FitzGerald returned to Bowen Island the following two summers to sketch and paint. With watercolours and coloured crayons he concentrated on seashore subjects provided by rocks and driftwood. His focus was on the microcosm of nature, with its complex interrelationships of shapes, whereby the shore became a universe of elements to be ordered. FitzGerald considered nature to be a living and organic entity that required the artist to see it as an organized and unified whole, a perspective that is exemplified in the drawing Driftwood, 1944.

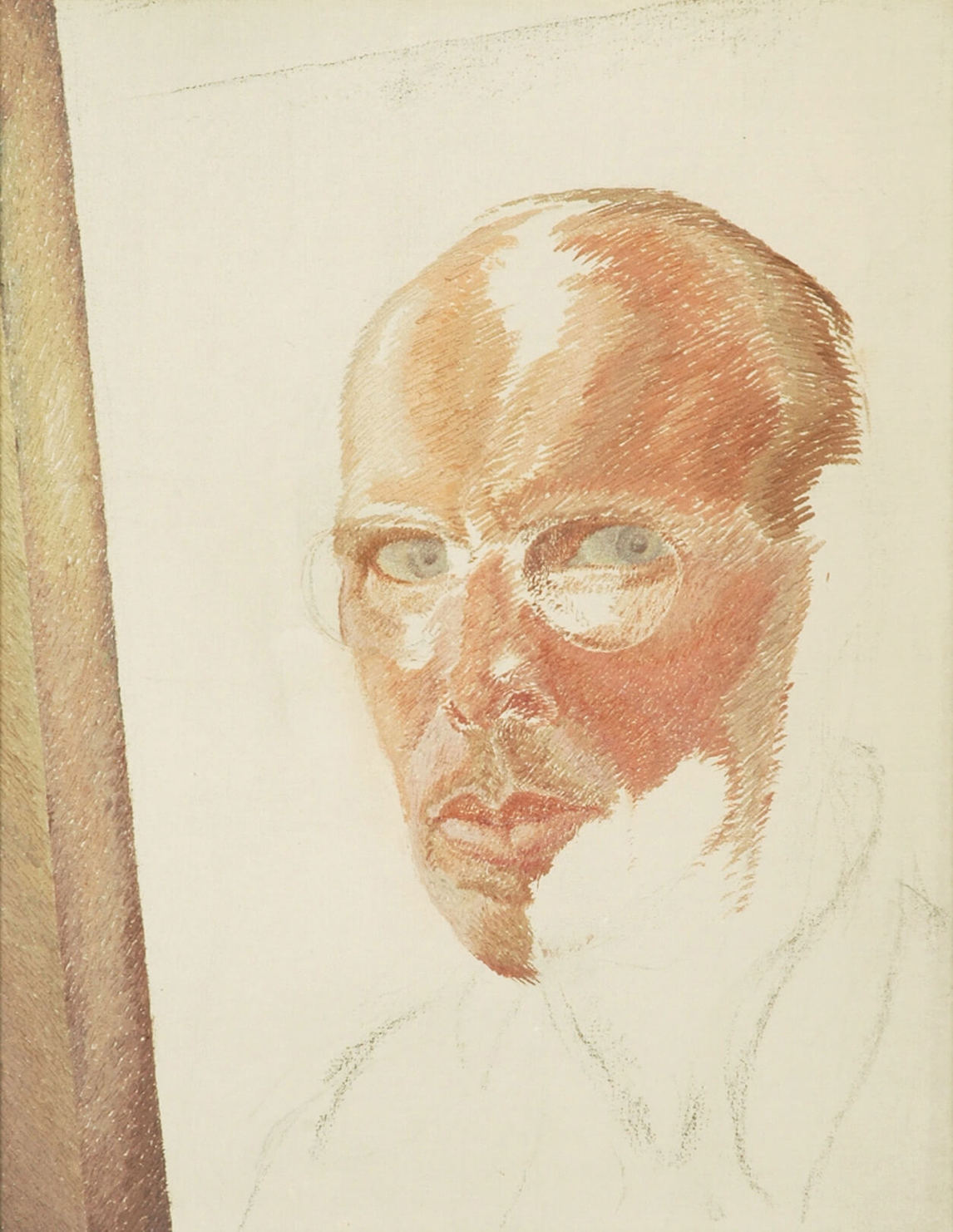

FitzGerald’s responsibilities at the Winnipeg School of Art were increasingly demanding, although the 271 students registered for the 1943–44 session were fewer than during the Depression years of the early 1930s. A sequence of twelve self-portraits, which probably date from 1945, reveal the artist as tormented and anguished, as found, for example, in the strained expression in the only work in oil (Self-Portrait, c. 1945) among eleven watercolours. While the reason for FitzGerald’s agitation is not certain, a contributing factor, apart from his frustration at not having more time for his art, may have been that his long-standing romance at the Winnipeg School of Art with former student Irene Heywood Hemsworth (1912–1989) was ending. His problems precipitated an illness that prevented him from teaching or accomplishing any work for about three months. He decided not to return to British Columbia in the summer of 1945, and he did not complete any major works in 1946 as his lethargy continued.

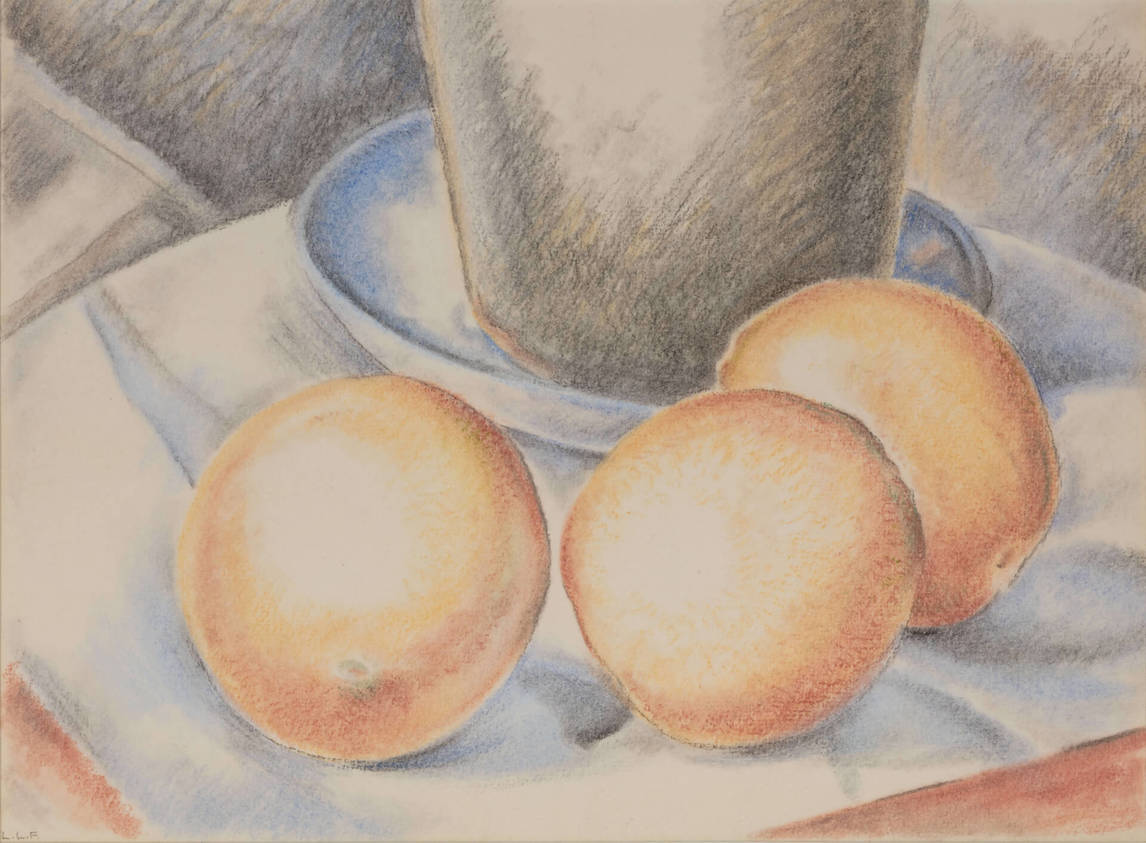

In September 1947 FitzGerald was able to take a year’s leave of absence from the school. He was given a year’s salary to pursue his art full-time, and that November the FitzGeralds left Winnipeg to spend the winter on Vancouver Island at Saseenos, about thirty-one kilometres west of Victoria on the Sooke Basin. They stayed in a cottage close to the waterfront that was perfect for working outdoors. The luxury of time away gave FitzGerald the impetus to consider new directions for his work. For example, the drawing Four Apples on Tablecloth, December 17, 1947, moves his work further into abstraction while maintaining references to the natural world—a trend that informs his practice after 1950.

A further year’s leave of absence was granted in April 1948 for the 1948–49 fall / winter term, and FitzGerald formally resigned from the Winnipeg School of Art in early 1949. Surprisingly, this new freedom prompted a period of doubt. Despite his early brilliance in oil, by the late 1940s FitzGerald questioned his ability to paint. Oil paint was certainly not his preferred medium, perhaps because the labour involved in applying small brush strokes to the canvas worked against his desire to capture the changing appearance of nature. FitzGerald wrote to his close friend Arnold Brigden (1886–1972) from Vancouver: “Have been working on a small (9 x 18) canvas having moments of ecstacy [sic] and hours of uncertainty with moments of being sure it is horrible—in other words the usual routine.”

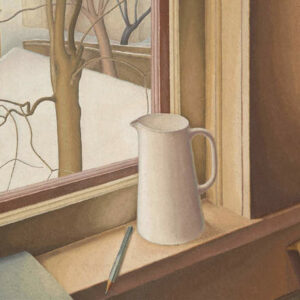

He faced the challenge head on in a studio set up in his garage. One result was the painstakingly executed Geranium and Bottle, 1949, with its meticulous attention to the distortions produced when looking through glass. Success on a small scale gave FitzGerald confidence to consider more ambitious paintings, leading to one of his crowning achievements, From an Upstairs Window, Winter, c. 1950–51. This superb painting demonstrates the harmony between abstract and naturalistic elements that he had sought throughout his career.

Plunge into Abstraction

FitzGerald had flirted with aspects of abstraction for years, but it was only in 1950, perhaps encouraged by the example of Lawren Harris, that he produced the first pictures that appear to depart from identifiable subject matter. “Abstraction offered the tempting opportunity to seize the almost incommunicable essence of the world—the forces of order that were manifested on a more mundane (visual) level in the petals of a flower or the spirals of a shell.” Now he was willing to work from memories rather than from observation. “I am now using this accumulated knowledge in some painting of an abstract nature where I can give more reign [sic] to the imagination freed from the insistence of objects seen, using colours and shapes without reference to natural forms.” Brazil, c. 1950–51, is one of FitzGerald’s earliest abstract paintings and was included in the National Gallery of Canada’s submission to the 1951 São Paulo Biennial exhibition.

In his late career FitzGerald toggled between abstract works and the type of figuration characteristic of his earlier work. In late 1954 and through 1955, FitzGerald created a number of still-life drawings and watercolours depicting apples, bottles, and jugs that recall his work from the 1930s and 1940s. These culminated in the last major painting of his career, Still Life with Hat, 1955. This picture may be considered a symbolic self-portrait—it is of the hat FitzGerald wore sometimes when he went sketching on the prairie. It must have come as a great disappointment when the picture was refused by a jury of his peers for the 1956 exhibition of the Canadian Group of Painters.

Despite this setback, FitzGerald received an acknowledgement of his contributions to the arts in Winnipeg when the University of Manitoba awarded him an honorary doctor of laws in 1952. And when he acted as a juror at the 1953 Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto, he was amazed to be treated with respect by his colleagues and accepted “as a living painter, and not ‘old hat.’”

FitzGerald died of a heart attack in Winnipeg, August 5, 1956, at age sixty-six. The memorial service in Winnipeg included a reading from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. According to FitzGerald’s wishes, his ashes were scattered over the prairie fields that he loved at Snowflake, Manitoba. The following year a Memorial Room in his honour was opened at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. This was followed in 1958 by the FitzGerald Memorial Exhibition organized by the Winnipeg Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Canada. In 1959 a public memorial plaque attached to a large rock was unveiled on the grounds of St. James City Hall near the Winnipeg neighbourhood where FitzGerald had lived. This memorial has subsequently been relocated to the northwest corner of Bruce Park, Winnipeg. But of the many tributes to this major Canadian artist, Lawren Harris’s perhaps best captured the quintessence of the man. “He was by nature and by necessity somewhat of a recluse…. He had a pervading gentleness which cloaked a constant inner firmness. He influenced others by his presence which was that of a saintly artist.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements