From the age of twenty-three, Bill Reid was on a lifelong journey to learn what it truly meant to be Haida. He was deprived of the fundamental experience of growing up Haida or living in the village of Skidegate during early childhood. Unable to learn the language, he initially struggled to relate to the Skidegate community. While the degree to which he achieved his personal quest for identity remains a topic of critical discussion, his contributions to Northwest Coast art and culture, as well as to environmental and social issues on Haida Gwaii, show his remarkable ability to harness the privilege he had as an outsider. These contributions were significant and should be underscored when discussing his legacy today.

Canadian Political and Cultural Dynamics

To understand Bill Reid’s art it is critical to consider the political and cultural dynamics that were in play in Canada when he began his career in the late 1940s. For Indigenous people, intergenerational knowledge and ways of life had been nearly destroyed by the effects of colonization, beginning with the implementation of the draconian Indian Act. The colonial government and its legislative policies had a direct effect on Reid’s mother, Sophie Gladstone. She was a survivor of the residential school system, having been sent to a year-round Methodist residential school in Coqualeetza, British Columbia, when she was ten years old. Students were prohibited from speaking their Native language. As well, she was indoctrinated with Christian beliefs and taught skills, such as sewing, that would enable her to assimilate into Euro-Canadian society. To add further shame, her marriage to a non-Native man meant that, while she could in theory retain her Haida identity, her “Indian” status was legally revoked and by extension she lost the automatic right to live in her village of Skidegate. Consequently, Bill Reid did not learn the Haida language or culture from his mother, who chose to ignore or hide her Haida-ness, believing that being “Indian” would not benefit her children. What she did carry instead was determination, inventiveness, and pride—qualities that would clearly have a positive effect on Reid.

As his awareness of colonial dynamics and history developed, Reid was able to discern the tragedy that had befallen his mother and her people. A total assault on Haida culture had been enacted through the potlatch ban. The potlatch is a ceremony that is essential to creative practices and cultural integrity among the Haida and other Northwest Coast Nations. But while the potlatch ban essentially banned Indigenous artistry, other colonialist initiatives aimed to promote Native arts and crafts with assimilationist and capitalist objectives in mind. For example, the B.C. Indian Arts and Welfare Society (BCIAWS) worked in collaboration with the residential school system and the churches to encourage students to produce Indigenous-style arts and crafts in ways that were detached from their traditional culture. Conflicting agendas were in play. As Scott Watson has noted, residential and day schools that were “mandated to assimilate Native children into the labouring classes of Canada and to erase Native culture, language, and land claims, would [also] promote Native arts and crafts.” Though Bill Reid was not educated in this system, he later copied designs from a publication by Alice Ravenhill, who was the non-Native leader of BCIAWS, to produce some of his early jewellery pieces, such as the Woman in the Moon Pendant/Brooch, c.1954.

In 1948 the BCIAWS and the British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria (now the Royal BC Museum) held a conference at the University of British Columbia, with a session addressing arts and handicrafts. Ellen Neel (1916–1966), a Kwakwaka’wakw artist, woodcarver, and entrepreneur, made a plea to the assembly of anthropologists, government officials, church leaders, and Native groups for the lifting of the potlatch ban. She stated that Native art was a “living art,” and that “the production of art was so closely coupled with the giving of the potlatch that without it the art withered and died.” She strongly advocated for reform, exclaiming, “If the art of my people is to take its rightful place alongside other Canadian art, it must be a living medium of expression. We, the Indian artists, must be allowed to create!”

While the commodification of arts and crafts continued to be seen as a potential way for Native peoples to generate income, an amendment to the Indian Act in 1951 lifted the potlatch ban. Traditional ceremony and artistic expression could continue anew. At this point, Reid was thirty-one years old and emerging as an artist. In time, his unique position as a highly skilled speaker, artist, and activist of mixed ancestry would come to play a pivotal role in asserting the relevance of Northwest Coast art in ways both audible and visible to Native and non-Native alike.

The Paradox of Preservation and Continuance

While in his late twenties and living in Toronto, Bill Reid quite by accident made a remarkable discovery that changed the course of his life. During a visit to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, he encountered a totem pole from his grandmother’s village. Reid’s mother, Sophie Gladstone, was born into the Kaadaas gaah Kiiguwaay, Raven-Wolf Clan of T’aanuu, and her mother, Suudahl (Josephine Ellsworth Gladstone), was from the ancestral village of T’aanuu itself. Poles from this village were removed in the early twentieth century and taken to museums; one such pole went to the Royal Ontario Museum, collected by the ethnologist Marius Barbeau (1883–1969). Reid saw this pole, known today as House 16: Strong House Pole, when he was searching for ideas to incorporate into his jewellery. It was located in the centre of a stairwell, which meant that Reid was able to examine the qualities of this Haida masterwork closely and in full detail. He had grown up on the West Coast, yet thousands of miles away in Toronto he came into close contact with the artwork of his ancestors. This masterwork would become a gateway into his Haida identity and a key object as a study in “deep carving”—a concept Reid understood as intrinsic to objects that constitute a physical embodiment of traditional Haida values.

Reid’s experience at the Royal Ontario Museum was made possible by anthropological endeavours that were fundamentally problematic. Collection and preservation were done with the intention of preserving the memories of a way of life that was under threat, but cultural materials were often taken from and sold by Indigenous people under duress, in a dynamic tantamount to stealing. These endeavours can be criticized for unjustly alienating Indigenous people from their own material culture. Though the term “salvage paradigm” was yet to be coined, the practice in which anthropologists and museum curators collected the material culture of Indigenous societies in order to preserve it from destruction was still supported, even at the beginning of Bill Reid’s career.

In 1947 two passionate anthropologists, Audrey Hawthorn (1917–2000) and Harry Hawthorn (1910–2006), specialists in Northwest Coast art, were brought to the University of British Columbia. In 1950 Wilson Duff (1925–1976) became the curator of anthropology at the British Columbia Provincial Museum (now the Royal BC Museum) in Victoria. Together, they continued the trend of collecting and preserving poles. Reid himself participated in trips to collect poles from abandoned Haida villages—first from T’aanuu and Skedans in 1954, and then from Ninstints (Nans Dins, SGang Gwaay Llnagaay) in 1957. These trips, especially to his grandmother’s village of T’aanuu (T’aanuu Llnagaay), affected Reid profoundly, as he was able to envision the splendour of Haida life in former times. He saw the “rescuing” of the poles as a successful achievement that was necessary as an act of preservation and continuance. “Badly weathered as most of them are,” he wrote, “the Haida poles show such a high standard of artistic achievement that their loss would have been tragic.”

Reid could see how useful these poles would be for contemporary carvers to copy. Yet he would never forget the “desolate beauty” of the poles as they “stood or lay among the ruins of the abandoned villages.” The pull to bring the old Haida ways into contemporary view sat at odds with the deep respect Reid had for the wisdom and beauty evident in the natural conditions that gave birth to Haida culture in the first place.

Reid may have felt that since he was a descendant of the Haida he was entitled to take part in the collection of poles—perhaps even that he had a moral obligation to save this part of his heritage. These acts of preservation were paradoxical because, on the one hand, taking the poles was unjust and problematic in many ways; the poles should have been left in their original locations, in keeping with respect for the integrity of the culture, though Reid did not know this. Yet, on the other hand, the collections that resulted, such as those at the Royal BC Museum and the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology, have been employed by many people today, including Haida, to support cultural activity and knowledge in the aftermath of colonization.

In 1952 Kwakwaka’wakw artist and Elder Naka’pankam (Mungo Martin, 1879–1962) was hired by the British Columbia Provincial Museum to carve new poles. Reid worked with Naka’pankam in 1957. This experience was of pivotal importance for Reid, because Naka’pankam was determined to keep the old ways from being forgotten and Reid could witness what remembering and enacting the traditions entailed. Naka’pankam told stories that he emphasized with songs and, smitten with Reid’s daughter Amanda, initiated a series of exchanges of handmade gifts that echoed the potlatching ceremonies integral to Northwest Coast societies. For Reid, Naka’pankam’s greatness was “projected as a matter of inner conviction.”

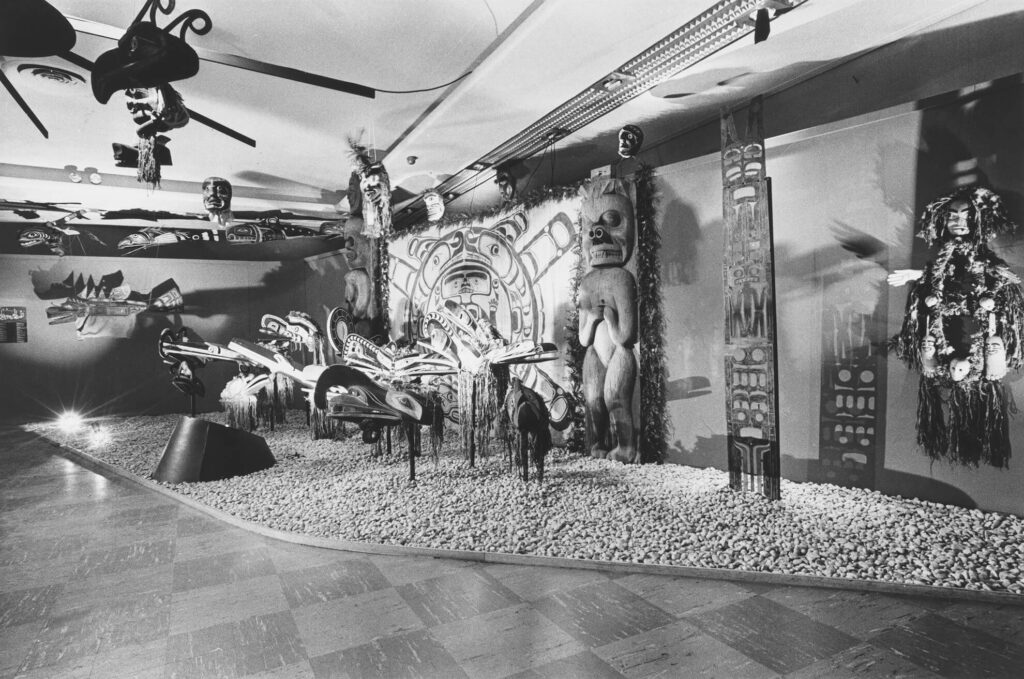

After this experience, Reid was hired by the University of British Columbia, initially with the assignment of restoring salvaged poles. However, it quickly became evident that preserving them in their authentic, weathered condition would not be possible. Carving copies made more sense. In due course, Reid and Kwakwaka’wakw carver Doug Cranmer (1927–2006) were commissioned to build the Haida Village, 1958–62. Suddenly, Reid himself was one of the contemporary carvers who would copy the old poles and bring them into the present day. Having prolonged access to works of old masters allowed Reid to copy them directly. This experience was invaluable to his artistic evolution. He was becoming skilled enough to develop his own artworks and still be confident that what he was producing was authentically Haida.

Haida Art and the Museum

During the 1950s Reid began to interact more directly with the Haida community. In attending his grandfather’s funeral in Skidegate in 1954 he gained a first-hand impression of the effects of colonialism that permeated the community. Reid became increasingly concerned for the fate of the Haida people during these years and was sensitive to the impact of the losses they had experienced, even though he had grown up in far different conditions. Though he began his career in a predominantly Euro-Canadian world and was educated to see through a privileged and Westernized lens, such views came into question as his career unfolded.

The Euro-Canadian world Reid had lived in was one in which Native cultural studies took place in museums and universities. The cultural “experts” were highly trained academics—historians and anthropologists whose methods of collecting and storing cultural knowledge were supported and endorsed by colonially founded governments. Many people who came to be Reid’s professional colleagues and friends, such as anthropologists Harry Hawthorn and Wilson Duff, were so-called academic experts. The relationships Reid formed in these institutional settings were central to his recognition as an important artist. He was both involved in museum endeavours and supported by them.

In 1954 Hawthorn directed a comprehensive “Indian research project,” which aimed to articulate the contemporary issues facing Indigenous peoples in Canada. The Hawthorn Report, as it came to be known, included a section on the economic role of Native arts and crafts, and focused on the potential of implementing instructional programs to increase the efficient output of “Indian [cultural] products.” The report explored marketing strategies that would promote the well-being of Native communities through the monetization of their art. The crafts considered to have potential were only those that had formed “a steady component of Indian-White exchange from the time of first contact.” The report demonstrated the colonial government’s ongoing insistence that detaching the handmade object from community and cultural functions was ultimately beneficial to the economic prosperity of Native people. Artists were encouraged to create works only to sell outside their communities, and their practices were seen as removed from their own culture.

In the decades to come, society’s understanding of the role of art in Indigenous cultures developed in parallel with Reid’s work and that of many other Indigenous artists. Despite all that the museum offered, Reid became aware of the fundamental difference between works produced in response to institutional initiatives and those rooted in lived cultural communities. In 1978 he finished carving the Skidegate Dogfish Pole in honour of his mother and the Haida community. He did this in relationship with the people of the community, who in turn raised the pole. “The other carvings were done all for the University, and under the direction of the museum people so they were actually museum pieces before they were even made,” he said. “This one will have some slight ceremonial symbolic significance, I guess.” Testimonies from the community confirm that the significance was profound.

Revival and Resistance

In 1956 Bill Reid wrote and recorded a monologue that appeared on CBC radio articulating his perspectives on what was then termed as “Indian art [being] dead art.” Those artists, he said, who were producing things in the traditional form, like Naka’pankam (Mungo Martin) and himself, were “atavists groping behind us toward the great days of the past, out of touch with the impulse and social pattern that produced the art.” (Atavists are those who revert to something ancient or ancestral in their way of thinking or being.) Reid’s statement reflected his belief in there having been a “classic” period that culminated in the nineteenth century, when Haida culture reached an apex of great expressiveness before being destroyed by colonial imperatives.

Reid felt that modern-day attempts to create authentic Haida art were essentially impossible and therefore needed new paradigms. He thus advocated that the only valid approach in the current time was to view the artwork, as it is shown in galleries and exhibits, “for its own sake,” for the universal qualities of beauty, strength, and emotional impact one would find in “any great art.” Among the many non-Indigenous scholars and historians, the way in which Reid framed this perspective gave rise to the notion that those who were making art and took inspiration from this classical past were part of a “renaissance.” In other words, they were rebirthing something that had died. Outside the Haida community, Reid came to be seen as this revival’s leader.

When Reid began his career in the 1950s, the art world, for the most part, had little interest in Indigenous art. This was mostly because within the framework of Western art a language for understanding art through an Indigenous lens had not yet been developed and, by extension, Indigenous makers were not recognized as artists. Up to this point, the field of art history viewed Indigenous output in “primitive art” terms and the study of it as little more than an ethnological endeavour. Anthropologists who had long been interested in historical Indigenous cultures wrote about, analyzed, and exhibited the work of contemporary artists within their distinct cultural frameworks. Others, however, viewed Indigenous artworks from the “classical” past within the context of other great universal art traditions. The renaissance perspective aligned with the revivalist objectives of curators, academics, and practitioners who wished to draw attention to the value of Indigenous art and its current-day creators. The Vancouver Art Gallery’s 1967 exhibition Arts of the Raven: Masterworks by the Northwest Coast Indian was an important moment: it had a part in a crucial shift in perspectives on Indigenous art.

Aldona Jonaitis has noted that the “renaissance metanarrative” can be seen as an invention of non-Native experts, many of whom were associated with museums and influenced by the art market. The story of the classical past dying and being reborn made the objects in collections more valuable and those who could give them their rebirth more powerful. Reid, in complex, interconnected ways, operated both as one of the experts and as an artist who benefited from his own works being valued as “archetypal for the renaissance.” The resilience and adaptability of Indigenous people during this time, however, has come to be viewed as change and continuance more than ending and new beginning. Indigenous art movements of the time, such as the Gitanmaax School of Northwest Coast Art, emphasized continuance and innovation, believing that “Native art has always been slowly evolving through education from the beginning of time.” As a result of these ideas, Reid is now considered to be part of a continuum, which includes him and his contemporaries, such as Naka’pankam, Doug Cranmer (1927–2006), and Tony Hunt Sr. (1942–2017) and Henry Hunt (1923–1985).

The phrase “contemporary art” is rather more apt than “renaissance” to describe the way Indigenous art began circulating on the periphery of the mainstream. Indeed, this very same situation was happening across Canada and the United States. What artists such as Reid were creating was intended for new audiences and contexts, which were significantly different from those of their ancestors who lived prior to the devastating impacts of the Indian Act. With time and the willingness of Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists, curators, scholars, and historians to see through an Indigenous lens and to develop a language for addressing Indigenous art, the voices of Haida artists and their ever-evolving artworks began to be seen and heard again.

Tensions of Being

As Haida/Tsimshian scholar Marcia Crosby argues, Bill Reid was neither at the end nor the beginning, but rather in the middle of Haida history; his perpetual state of being and becoming triggered tensions and contradictions in how Reid understood his own position. Because Reid’s Canadian and Haida identities were entangled, any story that assigns Reid to one “leaves too little room for the paradoxes and complications of Reid’s personal history, much less the multiple histories of Haida culture and society.”

Reid embodied many voices, and he was a kind of nomad, moving betwixt and between cultural contexts, be they artistic, conceptual, social, or physical. This mobility expanded the possibilities available to him and concurrently perpetuated ongoing internal and external questions about his identity. Sometimes Reid described himself as “a good WASP Canadian” and articulated a “non-Indian viewpoint,” while at other times he self-identified as Haida by taking the stance that he had “some right to be telling the story.” He described the Haida as “my folks” or “my only relatives,” while recognizing he had a “remote” relationship to the culture. He never permanently lived in Skidegate, the Haida village his mother came from, though he visited it many times as an adult.

Reid’s position as an artist of mixed ancestry was an often-shifting one, and he wrestled with what that meant. He embraced and enjoyed being able to perceive the world and his creative process in more than one way, explaining, “I do believe that the figures on that totem pole I am carving in Skidegate, for instance, grew inside that tree, as it was growing. And all I have to do is peel away the outer layers and there they’ll be. And, on the other hand, my mind tells me that’s complete nonsense and romantic balderdash. I can live with both points of view. And enjoy them both.” In terms of identity, Reid was an important catalyst for an ongoing critical inquiry into rigid categorizations and the fluidity of perceptions.

Reid was often said to embody the trickster Raven (Xhuuya), as seen in The Raven and the First Men, 1980, a potent and complex character in Haida mythology who is a magician, a transformer, a moody, self-indulgent bringer of chaos, and a Cultural Hero. Author and historian Robert Bringhurst views Reid’s position through a mythological lens. In Haida literature, he points out, it is difficult to discern if “the stories create the characters, the spirits who inhabit them, or the other way around.” The Raven is described as being greedy and mischievous, but also helpful and creative. He not only released humans into the world from a clamshell but also brought light (knowledge) to the world. He reminds humans that things are not always as they appear. Reid likened himself and was likened by others to the Raven because his path to becoming a well-known artist and of service to the Haida people was full of twists and turns that could not have been foreseen.

As Reid was formulating his identity, so was Canada. The development of the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal provides a tangible example of the tumultuous political dynamics of the day. Reid was invited to join a group of a dozen or more Native artists, including Alex Janvier (1935–2024), George Clutesi (1905–1988), Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007), and Henry Hunt, who were exhibiting their work in the Indians of Canada Pavilion. The exhibition in this pavilion would prove to be provocative and groundbreaking in shifting public perceptions of Indigenous art, history, and culture. Because Reid disagreed with the advisory committee, he chose instead to exhibit his work, Eagle and Bear Box, 1967, in the Canadian Pavilion, a building that aimed to portray the complex diversity of Canada from a different angle.

Formalism, Modernity, and Indigeneity

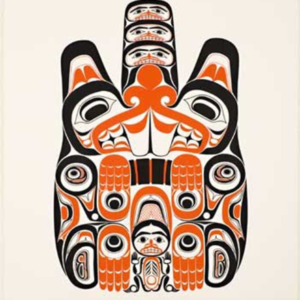

Around the mid-twentieth century historical Indigenous artworks began to be viewed through the lens of the modernist movement in art and formalism more broadly. In 1946 Surrealist artists Max Ernst (1891–1976) and Barnett Newman (1905–1970) mounted the exhibition Northwest Coast Indian Painting at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York City, which focused solely on the formal and stylistic qualities of the works. Thus, by the time Reid entered the Canadian art scene, the first show of Northwest Coast art employing formalism as a framing method had already been held. As curator and art historian Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse has explained, by the 1960s interest in the formalist aspects of Indigenous art had “supplanted all cultural concerns, setting the artwork adrift from its ties to territory or chiefly privilege.” As a result, on the Northwest Coast some art historians and curators began shifting Indigenous art objects from “the dusty halls of ethnography to the pedestals of the art gallery.”

For Reid, Bill Holm (b.1925), and Wilson Duff, who curated the 1967 exhibition Arts of the Raven: Masterworks by the Northwest Coast Indian, the use of formalist language helped to position Northwest Coast art within a universalist framework and as an expression of an “essential humanity.” This aligned and elevated the artworks to a position of status in the high art world, thereby increasing their global, cultural, and economic value. Highlighting individual master artists, such as Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw, 1839–1920), and clarifying the attributions to them—one of the great benefits of formal analysis—also aided the transition.

Reid had a part to play in almost every facet of this endeavour. Alongside creations made by Daxhiigang, his artworks were highlighted in exhibitions. With Duff, he wrote texts that promoted the appreciation of Northwest Coast art. And for Holm, he developed the language of formal analysis. Together with other artists, gallerists, and collectors, Reid benefited from the increased commercial value and viability of Northwest Coast art production.

Reid and his colleagues had envisioned the recasting of Indigenous objects as “art” as an act of cultural independence, recognition, and praise. However, from the standpoint of some of those engaged in Indigenous resistance and activism, it came to be recognized as an “act of suppression.” Producing art objects that could be detached from lived experience was counter to the goal of many artists, particularly those operating within Indigenous frameworks. The early 1980s spurred debates over access to Indigenous knowledge in the presentation of artworks, the need for it, and the sovereign right of First Nations artists to determine the context in which their work is shared. The notion that Westerners could locate universal values in artworks based on generalized standards was seen as leading to the effacement of local knowledge. As Marcia Crosby argues, foregrounding the aesthetics of an object over its social and political meaning results in a “depoliticized Indian artist.” In other words, assigning meaning to an object without being familiar with the exact context or conditions in which it was made leads to misinterpretations and takes authority away from its makers.

Though Reid had supported the inclusion of Northwest Coast art in the institutional “white cube” venues of the international modern art world, by 1983 he was wrestling with exactly that question, stating, “I don’t think you can take the design and the art without taking the people as well.” At this time, the voices of Haida people were ringing out in resistance to ongoing colonial oppression and control. Within a few years, many people of Haida ancestry were literally in Reid’s art, paddling Loo Taas, 1986.

As Reid’s reputation developed, he became increasingly engaged with the political and social issues of the Haida Nation. In 1976 he began work on a seventeen-metre house-front pole for the Band Council office in Skidegate, his mother’s home village. Reid worked on site in Kay Llnagaay (Sea Lion Town) with Haida artists Guujaaw (b.1953), Robert Davidson (Guud San Glans, b.1946), and Gerry Marks (1949–2020), and Nuu-chah-nulth carver Joe David (b.1946). Reid hoped to garner both community financial investment and the participation of locals in the project. Although Reid did not receive the monetary donations and attention he hoped for, by the time the pole was raised in 1978 the community expressed a great deal of appreciation and held a ceremonial celebration and feast. A few decades before, in 1954, Reid had been given the Haida name Iljuwas (Manly One, or Princely One), and at the time of the pole raising this was publicly confirmed.

Between 1985 and 1987 Reid lent his fame in both words and work to Haida resistance against the industrial logging that was destroying Gwaii Haanas, the southern region of Haida Gwaii. The Haida Nation had resolved to reject the government-endorsed project, leading the Haida community and their allies to form a respectful blockade at historic Athlii Gwaii (Lyell Island) to stop forestry companies from logging on their ancestral homeland. In February 1986 Reid stood before the government’s Wilderness Advisory Committee and expressed his contempt for the ongoing logging that was being permitted on Haida Gwaii.

The following year Reid decided to withhold work on the full-scale version of Spirit of Haida Gwaii, 1986, his major commission for the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C. He chose to use his influence to attempt to persuade the government to comply with the people’s wishes, telling the officials that the use of Haida symbols as “Canadian window dressing in Washington” was inappropriate when the Haida people were being denied the right to preserve their natural homeland and heritage. Later that spring, he responded to the request of Haida Chief Chee Xial (Miles Richardson Sr.) to help maintain the blockade. When Reid was brought in, he sat in the middle of the road by himself, whittling a piece of wood. At the time, many Haida had dedicated months to participating in the blockades and needed to get back to their regular jobs. When the loggers arrived and realized it was Bill Reid blocking their way, they turned around and left, never to return. Bill Reid had become the “last blockader.”

Reid’s final significant activist gesture came with the creation of Loo Taas, 1986, a project that aligned the cultural revitalization of the Haida community with the political and environmental concerns of the day. The Haida movement to save Gwaii Haanas had been a major focus of activism since 1985. Concurrently, Loo Taas was brought to life in and with the Skidegate community. After her appearance at Expo 86, the graceful ocean-going canoe was paddled up the coast, visiting many communities along traditional trade routes and reigniting knowledge and pride in Haida ways of life. Organizers agreed that this journey would be a “mission of peace,” but if the government’s position did not change it would become a “war run.” When Loo Taas reached Skidegate, a huge homecoming celebration got under way. It was July 11, 1987, and, just as the feast was beginning, a helicopter landed in the ball field, carrying Canada’s minister of the environment, Tom McMillan. To the joy of all, he announced that the province and Canada would be joining the Haida in the protection of Gwaii Haanas.

Today, Loo Taas proudly sits at the Haida Gwaii Museum at Kay Llnagaay and continues to be involved in ceremonies and other local activities. She was probably Reid’s most profound achievement because of the role she has had and continues to play in the health of the Haida Nation. Reid was born into a time when Indigenous cultural practices were illegal, yet the end of his life witnessed him entrusting the Haida Nation with a beating heart—a Wave Eater—a canoe that would be nourished by being on the water and actively paddled by generations of Haida people.

Legacy to a Thriving Spirit

Bill Reid is unquestionably a major figure in Canadian and Haida art history. Both as a person and as an artist, he wrestled with many of the difficult and beautiful aspects of Haida-ness and Canadian-ness that were arising alongside agendas of decolonization in the later twentieth century. At the core of his life’s project, whether spiritual, political, social, or artistic, was a question of identity: how, in an ever more complex global dynamic, do we come to see, know, and understand ourselves and each other?

Reid received many accolades during his lifetime, including the National Aboriginal Lifetime Achievement Award, appointment to the Order of British Columbia, and the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada’s Allied Arts Medal. He would also turn down appointment to the Order of Canada to proclaim his support for the Haida. Several institutions have been founded in his honour, such as the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art in Vancouver, the Bill Reid Centre for Northwest Coast Studies at Simon Fraser University, and the Bill Reid Teaching Centre (Yaahl SGwaansing Naay, or Solitary Raven House) at the Haida Heritage Centre at Kay Llnagaay in Skidegate. At the teaching centre, studios and classrooms provide “a new generation of Haida apprentices” with facilities to “learn their craft from master carvers and designers, ensuring the continuation of Haida art forms and techniques.”

In the words of Martine J. Reid (b.1945), “Reid was instrumental in introducing to the world the great art traditions of the Indigenous people of the Northwest Coast of North America.” His legacies, she writes, include “infusing those traditions with modern techniques and new conceptual forms of expression, styles, genres and media; [and] teaching and influencing emerging artists.”

The ancestral narratives and formal techniques that energized Haida art gave Reid a framework within which to articulate his identity and beliefs with both reverence and playfulness. His art came to embody a way of being that was both principled and adaptive, both structured and fluid—and, above all, well crafted and joyful. He believed that one’s identity was most profoundly constructed by what one does or makes.

Beyond the accolades and awards, Reid’s legacy successfully drew attention to Haida Gwaii and the way in which its artists and traditions are recognized. Younger generations of Northwest Coast artists such as Don Yeomans (b.1958), Jim Hart (7idansuu, b.1952), Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (b.1957), and Gwaii Edenshaw (b.1977) acknowledge the impact of Reid and his legacy. Meanwhile the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art, which opened its doors in 2008, provides support to the next generation of artists and maintains a crucial link between Haida Gwaii and the city of Vancouver. In 2013 Daxhiigang (Charles Edenshaw) was given a major retrospective at the Vancouver Art Gallery; and in 2018 the Toronto International Film Festival screened Edge of the Knife (SGaawaay K’uuna), directed by Gwaai Edenshaw, the first feature film to be made entirely in the Haida language. Today, Haida Gwaii is a vibrant place where art, song, and ceremony are once again practised. The spirit of the people thrives.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements