Françoise Sullivan achieved recognition as a dancer, sculptor, conceptual artist, performance artist, and painter. She pursued formal training in most of these areas but also continued throughout her career to develop her practice in response to encounters with important artists of her day, and also through her travels and friendships. Her openness to new ideas and her willingness to experiment have helped make Sullivan one of the most enduring and innovative artists working in Canada.

Dance

Françoise Sullivan started taking classical dance lessons at the age of eight. Her teacher, Gérald Crevier (1912–1993), encouraged her, along with his other most talented pupils, by taking them to see the Ballets Russes when the troupe stopped in Montreal during its North American tours. During these early years, Sullivan and her friends lived and breathed dance, regularly putting together recitals for the neighbourhood children.

Sullivan attended the École des beaux-arts in Montreal from 1940 to 1945, focusing on painting. In spite of her success at the École, she temporarily put painting aside after graduating, and she decided to concentrate on dance. She had become familiar with modern themes and techniques in art through her encounters with painters such as Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), Alfred Pellan (1906–1988), and Fernand Léger (1881–1955). Now she sought to transfer what she had learned into movement, drawing in particular from the discussions she had had with the Automatiste group about overcoming the gap between mind and body and expressing feelings in a way that was as direct, as unmediated as possible. But there were no established modern dance schools or troupes in Quebec at that time, and in 1945 Sullivan moved to New York to follow her passion.

There she took classes from several prominent dancers, including Hanya Holm (1893–1992), Martha Graham (1894–1991), Pearl Primus (1919–1994), and La Meri (1899–1988), and the choreographer Louis Horst (1884–1964). But her most important mentor was Franziska Boas (1902–1988). Boas favoured improvisation as a pedagogical tool; she would pick up a drum or other exotic instrument from her vast collection to mark rhythms and encourage her students to move spontaneously. This approach, diametrically opposed to classical training, was designed to free the body and allow it to follow its own impulses. Sullivan studied with Boas for two years and became a charter member of the groundbreaking, if short-lived, interracial company, the Boas Dance Group (1945–46).

After Sullivan returned to Montreal, she and her friend Jeanne Renaud (b. 1928) performed their first modern dance recital in 1948. It included Daedalus (Dédale), Black and Tan, and Duality (Dualité), works in which the dancers shunned classical dance movements and explored simple expressive gestures born out of improvisation exercises. Sullivan soon made a name for herself as an innovative and prolific choreographer, and in the 1950s she benefited from the early days of television by creating choreographies for Concert Hour (L’heure du concert), a classical music television program that aired in English on CBC Television and in French on Radio-Canada from 1954 to 1958.

Sullivan’s best-known dance project remains Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige), created in February 1948 outside the town of Otterburn Park, southeast of Montreal. It was planned as a component of a cycle representing the four seasons. In each segment of the overall project, Sullivan intended to improvise a dance in nature, interacting with the elements. The first of the four, Summer (L’été), was danced in June 1947 on a beach strewn with pink granite boulders that reached into the sea at Les Escoumins in the Côte-Nord region of Quebec. In a bright red bathing suit, Sullivan jumped from rock to rock, let herself be animated by the wind, and finally disappeared over the hills. The winter dance, Dance in the Snow, was a dialogue with snow, performed in silence except for the crunching of Sullivan’s steps on the brittle surface. Spring was meant to be danced in the morning rain in Old Montreal, and fall in a forest among fallen leaves, but these seasons were not realized at the time. Scheduling was tricky, always dependent on favourable weather, and Sullivan had begun to turn her attention to new projects.

Throughout her later career, Sullivan continued to dance and choreograph when opportunities arose, and she had a strong impact on a new generation of dancers and choreographers, including Paul-André Fortier (b. 1948), Robin Poitras (dates unavailable), Daniel Léveillé (b. 1952), Manon Levac (b. 1958), and Ginette Laurin (b. 1955). Her practice was always marked by improvisational techniques, sweeping and unrestricted gestures, and the use of the whole body, including the face, to express emotions.

Dance was arguably the medium in which the Automatiste movement was most fulfilled, by breaking the duality between mind and body and giving free rein to raw energy. As Sullivan explained in “La danse et l’espoir” (“Dance and Hope”), the 1948 essay that was included in the Refus global (Total Refusal) manifesto, “The dancer must liberate the energies of his body.… He can do so by putting himself in a state of receptivity similar to that of a medium.”

Sculpture

Françoise Sullivan began sculpting because it afforded her the opportunity to work in close proximity to her children. She and husband Paterson Ewen (1925–2002) had their first son in 1950, and three more boys followed over the decade. Sullivan set up a studio in the family’s garage in 1959, and started experimenting with clay and metal.

Sullivan’s friend Jeanne Renaud (b. 1928), a dancer and choreographer, often asked avant-garde artists to design sets for her recitals. One day Sullivan accompanied Renaud on a visit to sculptor Armand Vaillancourt’s (b. 1929) studio. Sullivan was immediately fascinated by the large sculptures and heaps of metal scraps crowding the workplace. At that first meeting, Vaillancourt took a few minutes to give her a demonstration of how he worked. He showed her the rudiments of arc welding and how to cut metal with a blowtorch. He then placed a welding helmet on her head, inviting her to experiment. While Renaud and Vaillancourt discussed their collaboration, Sullivan managed to produce two small works. In 1960 she registered as a part-time student at the École des beaux-arts to learn more, and took a sculpture course from Louis Archambault (1915–2003), a Quebec artist influenced by Surrealism. To further hone her skills, Sullivan took welding lessons designed for plumbers and construction workers at the École des métiers in Lachine.

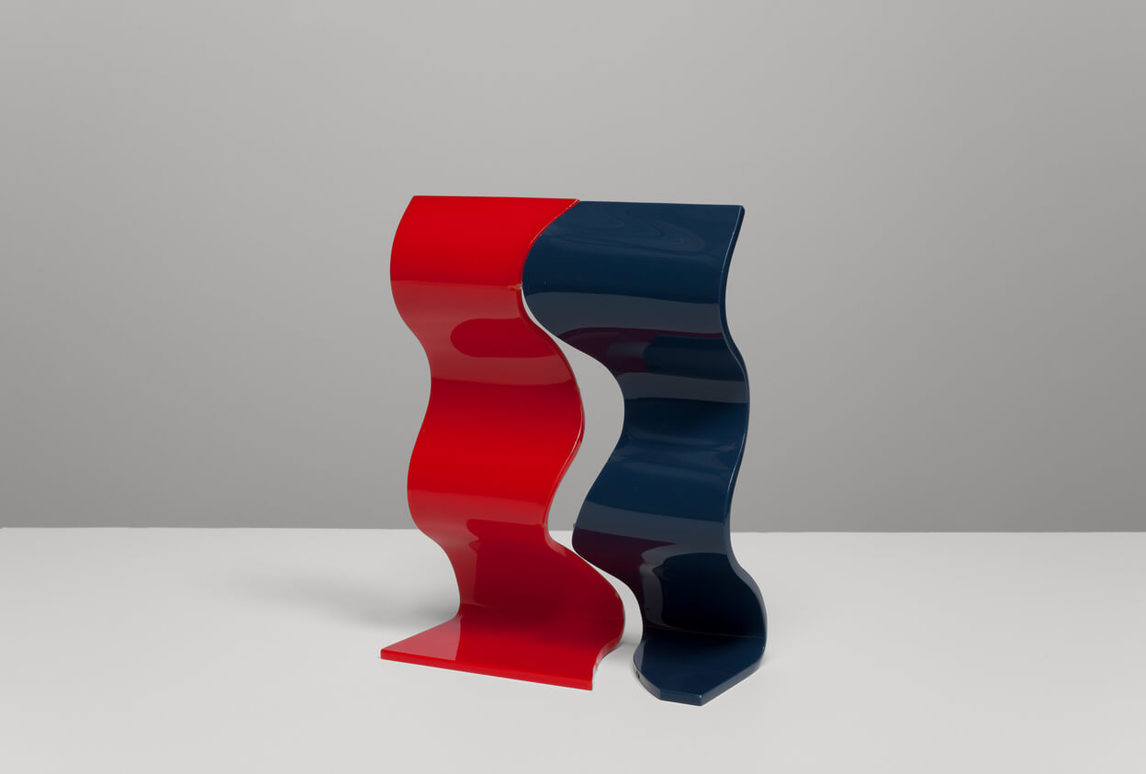

Sullivan liked the corporeality of sculpture, which reminded her of dance: “Sculpture, for me, was a physical thing. It followed the Automatiste thought.” And her first efforts highlight the physical engagement sculpture relies on, as well as the materiality of the medium: she folded metal shapes and welded them together, leaving the joints visible. In Concentric Fall (Chute concentrique), 1962, and in The Progress of Cruelty (Le progrès de la cruauté), 1964, for example, she managed to preserve the rawness of metal while making the industrial material look surprisingly light and infused with energy. The effect results from the interplay between matter and negative space, and the contrast between stability and asymmetry, showing a keen understanding of three-dimensional space on the part of the artist. Even after 1964, when Sullivan started painting sculptures such as Callooh Callay, 1967, and Aeris Ludus, 1967, in bright colours, the process of cutting, bending, and assembling continued to show through.

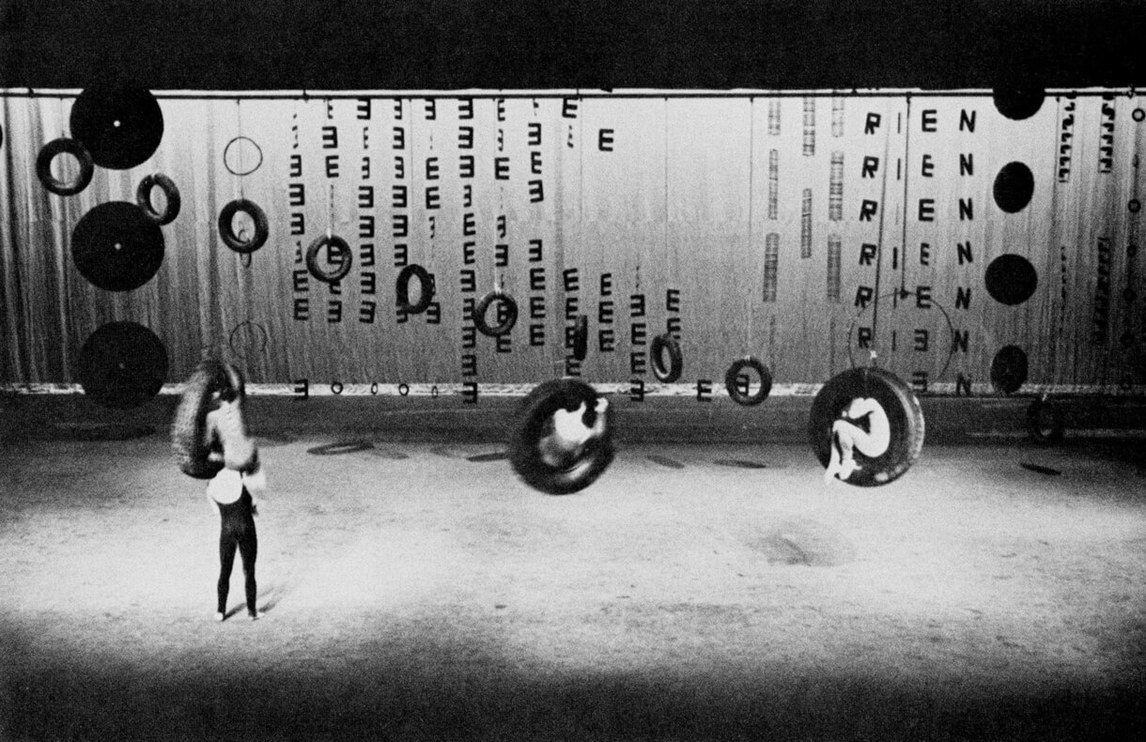

Through the 1960s Sullivan created large-scale installations that served as dynamic sets for dance works by Jeanne Renaud and Françoise Riopelle (b. 1927). In 1965, for Curtain (Rideau), choreographed by Renaud, Sullivan conceived a screen of suspended metal pieces that dancers knocked against each other to create a soundscape. In 1967, for the set for Centre-Momentum (Centre-Élan) by Le Groupe de la Place Royale, Quebec’s first modern dance troupe that was under the artistic direction of Renaud, Sullivan ingeniously integrated tires on which the dancers climbed and swung.

By the mid-1960s malleable synthetic materials such as Plexiglas afforded a range of new possibilities for creators. The move to plastic, increasingly used to make furniture, toys, and household goods, seemed natural for Sullivan, who wanted to integrate the art objects she created into the everyday. As she explained, “Sculpture is the concrete and rigorous expression of my evolving grasp of the atmosphere and tone of our time.”

Working with plastic required a whole new set of techniques. Sullivan had heard that the owner of Hickey Plastics, a company specializing in the production of plastic housewares and gift items, appreciated art. She contacted him and was soon allowed on the factory floor, where she observed employees crafting their products and started to experiment with materials and tools, getting tips from the workers she rubbed shoulders with.

While her first untitled Plexiglas sculptures made use of vibrant colours, with works such as Of One (De une), 1968–69, Sullivan soon moved to translucent plastics that could best evoke weightlessness. Surprisingly, Sullivan’s use of industrial materials and processes never eradicated a sense of the human touch. The sensuality that characterized her dance performances was always present in the shapes and the dynamism of her sculptures.

Conceptual and Performance Art

The 1970s was a period of experimentation for Françoise Sullivan, as for many artists of her generation. One of the preoccupations they shared was the commodification of art and what they considered to be its senseless accumulation in institutions. As Sullivan explained in 1973, “I have in my heart a great love for art, but I am uncomfortable when I say that word. The artist devotes his life to doing a job that is becoming impossible. Our world is saturated with art objects. What should he do then?” Reading Hal Foster (b. 1955) and others, it seemed to Sullivan that the art world was falling apart.

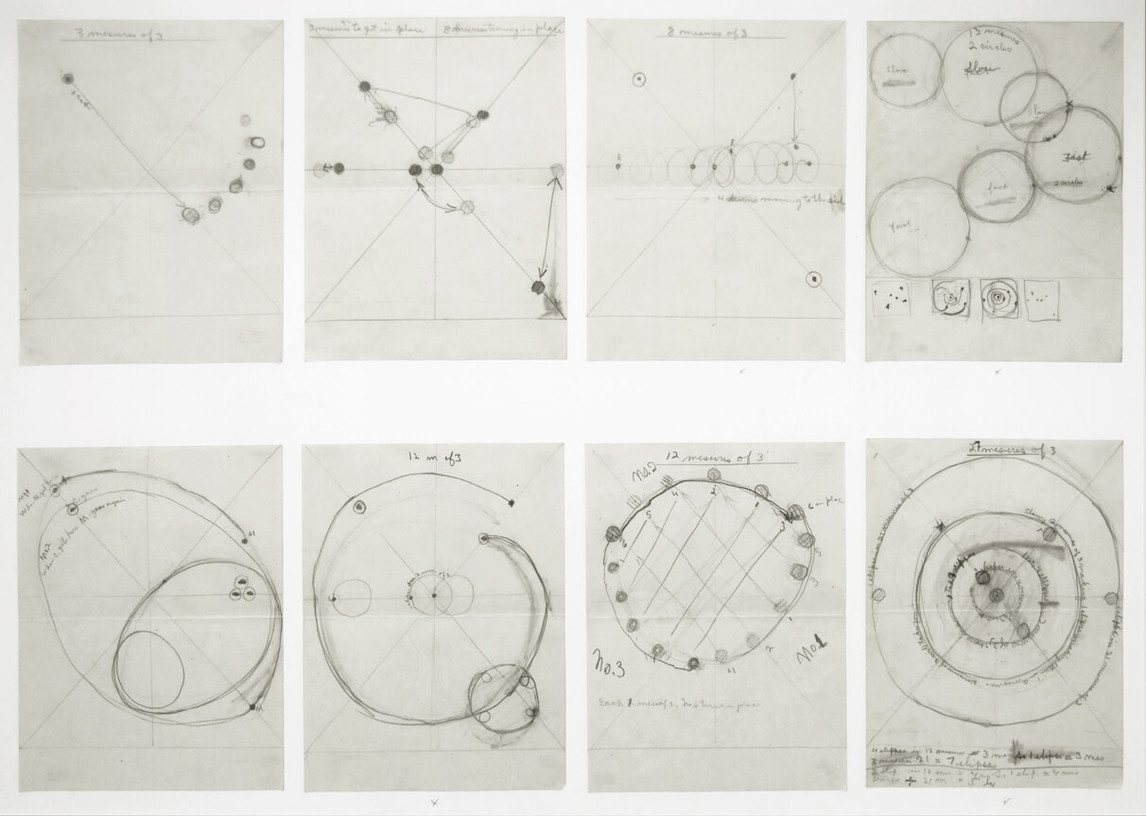

Sullivan defined conceptual art as a “mental approach on the part of the artist.” For her, “the means and materials by which [artists] concretize this approach [are] of secondary importance. This attitude gives priority to attitude over achievement.” This experimental position gave her the latitude to freely explore photography, photomontage, writing, and performance art. She also showed personal mementoes and notebooks from a recent trip to Italy, as well as her bodily fluids, at Galerie III in Montreal in 1973, in an exhibition simply titled Françoise Sullivan. In her work in all these media, she highlighted the poetry that traverses everyday life, the blurring of the lines between art, life, and dream, and the ways archetypes and myths still find echoes in modern concerns. She did this most vividly with her use of archetypal forms, such as the circle in her performance work, and with her integration of figures from Greek mythology in her photomontages.

Some of Sullivan’s best-known works from the period are performances. They belong to what Allan Kaprow (1927–2006), a pioneer in establishing the concepts of performance art, had described in the early 1960s as Happenings, art events that did not fit in the established traditions of visual arts, theatre, or dance but nevertheless allowed artists to experiment with body motion, sounds, the environment, and written and spoken texts, as well as to interact with other performers or the public. Sullivan’s first performances consist of loosely scripted walks that were documented photographically. In 1970 she walked from the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal to the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal. As she strolled she took pictures of what she saw. In 1973 she had herself photographed as she explored an industrial park populated with oil refineries in Montreal’s east end. In 1976 she created a guided walk for the public through Montreal’s cultural past, involving exhibition cases and panels she had placed on the sidewalks. And in 1979 she produced Choreography for Five Dancers and Five Automobiles (Chorégraphie pour cinq danseuses et cinq automobiles), a piece to be walked and danced, and during which five performers and five automobiles interacted in Old Montreal.

Around 1971, inspired by a dream of being shut out of her own home, Sullivan began to photograph doors and windows in condemned buildings. While in Italy and Greece, she created photomontages of suburban houses and phone booths filled with large stones. During a trip to Ireland, Sullivan embarked on a series of intensely physical performances in which she painstakingly moved stones of different sizes to block and unblock doors and windows (Blocked and Unblocked Window [Fenêtre bloquée et débloquée], 1978). This was a reference to a social history in Ireland, when British lords applied a housing tax on a home’s number of apertures and the Irish resisted by blocking their windows and doors. In 1979, in a Happening titled Accumulation that took place at the Ferrare museum in Italy, she cleared a doorway by removing the stones that blocked it, arranging them into a large circle in an open space. Meanwhile, inside the museum, a young woman was dancing Daedalus (Dédale), Sullivan’s choreography from 1948. She also made works that integrated the ruins at Delphi, in Greece, using them as a material more than as a backdrop: for example, in Shadow (Ombre), 1979, she had herself photographed by David Moore (b. 1943) as she walked through them, creating shadows with her body on the wide expanses of stones.

The same ideas recur in many of these works in a variety of mediums, and the line between performance and documentation blurs. At this point in her career, the medium was secondary for Sullivan: “What really counted was the idea.”

Painting

As a child Françoise Sullivan loved painting and regarded it as “the greatest of all the arts.” That is why she chose to study painting when she enrolled at the École des beaux-arts in 1940, but her academic training left her wanting more. She was attracted to the European modernist works she saw in books and at exhibitions, and she integrated broad brush strokes and a non-naturalistic palette reminiscent of the work of Henri Matisse (1869–1954), André Derain (1880–1954), and others into early paintings such as Amerindian Head I (Tête amérindienne I), 1941, and Portrait of a Woman (Portrait de femme), about 1945. Her meeting with Paul-Émile Borduas and the other artists who would become the Automatistes also had an important impact on her work. She never considered herself an Automatiste painter, however: “I never managed to make Automatiste paintings. But I could do it with dance.” She decided to pursue dance while she was young, hoping she would return to painting one day.

Sullivan did not pick up her brushes again until the late 1970s. The art world was then focused on new types of practices, such as performance and installation art, which Sullivan had been exploring for a decade. Going against the current, she returned to her first love. “I chose to work in painting, with its traditional materials, as a means of resistance, because this is the medium that had been most denigrated over the past thirty years.”

Sullivan’s mature paintings bear the traces of her experience as a dancer, sculptor, and performance artist. Organized in series, they highlight the specific artistic issues Sullivan was working through at the time. The Tondo Cycle, 1980–82, for example, consists of large circular canvases. By being visibly cut up and reassembled, they emphasize the human labour needed to make them. The Cretan Cycle (Cycle crétois), 1983–85, by its use of imaginary figures with mythological overtones, reflects Sullivan’s ongoing interest in myth and archetypes.

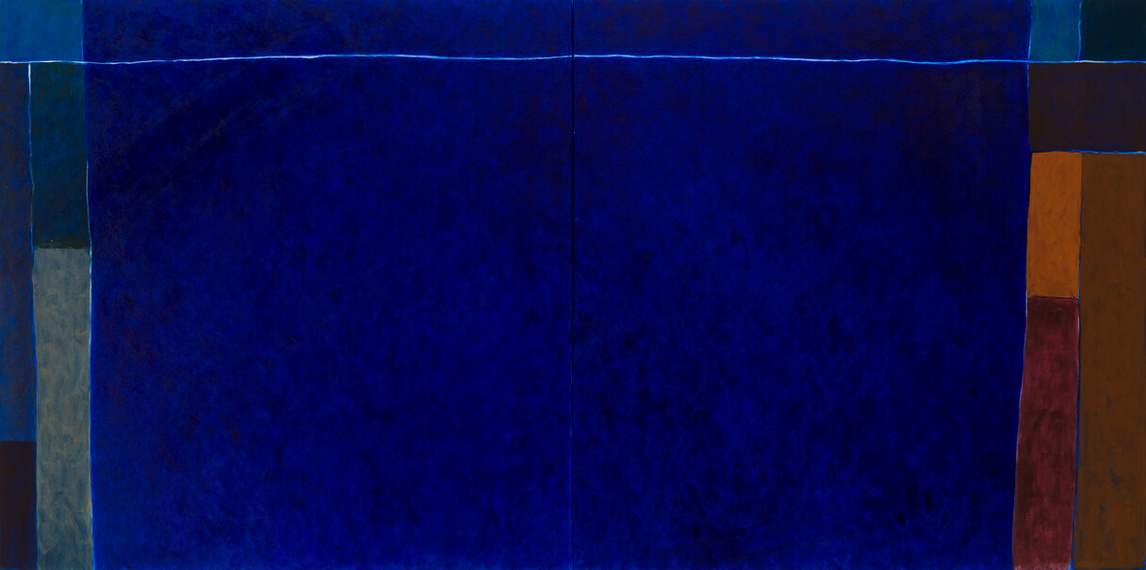

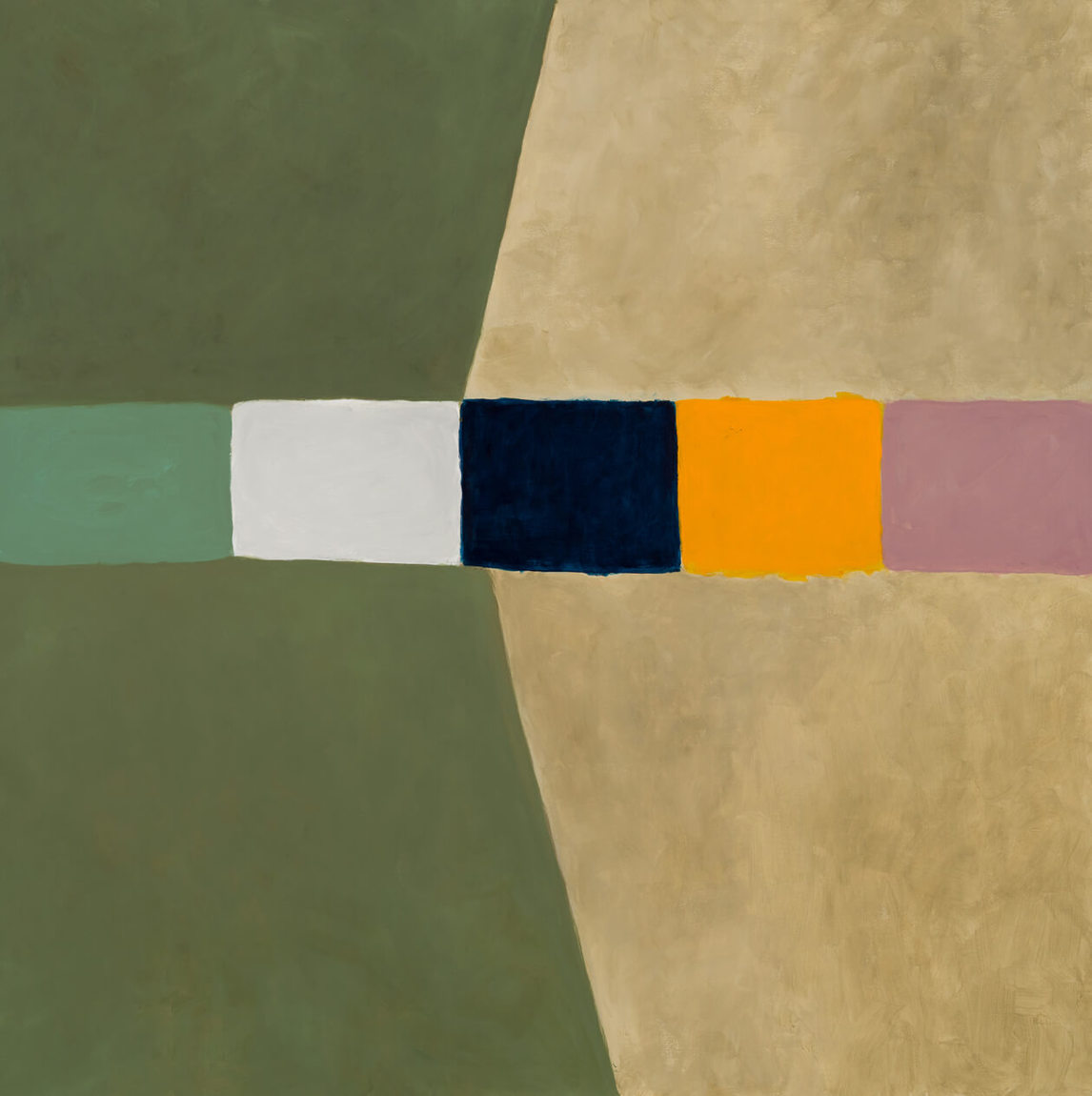

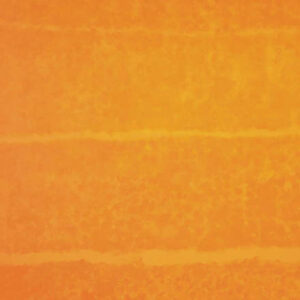

From the early 1990s, Sullivan’s painting gradually moved toward abstraction. Series such as Reds (Rouges), 1997–2016, Homages (Hommages), 2002–03, and Oceanic Series (Série océane), 2005–06, present monochromatic surfaces that are animated by slight variations in hue and brush stroke, creating a pulsating effect. In the series Edge, 2007; Games (Jeux), 2013–15; Proportio, 2015; and Bloom, 2015–16, interior subdivisions and relations between asymmetrical fields create visual tension and drama while preserving a fragile harmony. Sullivan approached the series Only Red, 2016, in much the way she created conceptual art: she gave herself a simple task, making paintings from a selection of reds, and developed it through repetition.

Sullivan’s mastery of colour is remarkable. Her works in subtle camaïeu, or those constructed from strident, idiosyncratic juxtapositions of colour fields, appear to glow from within. For Sullivan, colour is pure emotion, meant to resonate on a primal level. “I would like,” she explains, “to recover the vibration that occurs in the instant when life is felt intensely, and provoke this sensation of the self in a present and ephemeral moment.” This effect is reinforced by Sullivan’s expressive brush strokes and her predilection for large-format paintings that create an immersive viewing experience.

The greatest challenge that painters face with abstraction is to continuously renew their work and create engaging surfaces without the help of recognizable motifs. For Sullivan this means working through improvisation. She never paints from sketches, but rather tries to generate a dialogue between herself and the work. As she puts it, “The true satisfaction of art is found at the level of experience. The work is constructed as it is being made, in dialogue between the artist and the painting, between the brush stroke and the form that emerges from the process.” With her dance training, Sullivan is probably more aware than most other painters of the effect of her movement, at once spontaneous and controlled, as she creates. This is one of the unique characteristics of her paintings and an important source of their energy.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements