Françoise Sullivan actively participated in the Montreal art scene for more than seventy years and was a key player in its cultural events. As a leading woman member of the Automatistes, she brought a new visual sensibility to art in Quebec, and her writings and lectures were pivotal at a time when criticism focused primarily on the painting practices of male artists. Although she constantly experimented and often changed her approach to art making, she remained committed to self-expression and to improvisation as a way of unleashing creative energy.

Being an Artist and a Woman

Gender was rarely discussed in the writing about art in Quebec before the 1970s. From the 1920s on, however, the presence of women’s work in art exhibitions was often seen as worth noting because it was unusual. Even when their work was considered innovative and significant, as was that of Prudence Heward (1896–1947), Sarah Robertson (1891–1948), and Anne Savage (1896–1971), it was nevertheless qualified as “feminine” and therefore different in nature from that of their male counterparts. In an early essay, “La peinture féminine” (“Feminine Painting”), written in 1943, Françoise Sullivan shared this popular bias about the female artist: “Painting, under her fairy-fingers, is transformed; we are far from male painting, his art is of a different sensibility.”

In her own artistic career, however, Sullivan never seemed limited by stereotypes. In fact, women were unusually well represented in the Automatiste group, of which Sullivan was a member in the 1940s: seven of the sixteen signatories of the Refus global (Total Refusal) manifesto were women, and they thrived within the context of the movement’s rejection of established artistic traditions. Sullivan also avoided resorting to the essentialist strategies that became popular in feminist circles in the 1970s with the work of Judy Chicago (b. 1939), Nancy Spero (1926–2009), and Mary Beth Edelson (b. 1933), who drew heavily on female genital imagery or the figure of Gaia, the ancestral mother of all life, for subject matter. Sullivan didn’t think of herself as a feminist, or even as a woman artist, but as a human being working with whatever capabilities she has. As she explained in a talk at the National Gallery of Canada in 1993, “I never thought of refraining from doing something because I was a woman; I just did it.”

An Artist of Many Practices

Few artists have worked across as many media platforms as Sullivan has; she was a pioneer in how she moved so freely from one discipline to another. As a teenager she studied painting at the École des beaux-arts in Montreal from 1940 to 1945; pursued a very successful dance career as a young woman; became a renowned sculptor after the birth of her children; practised conceptual and performance art throughout the 1970s; and then finally returned to one of her first loves, painting, in 1979.

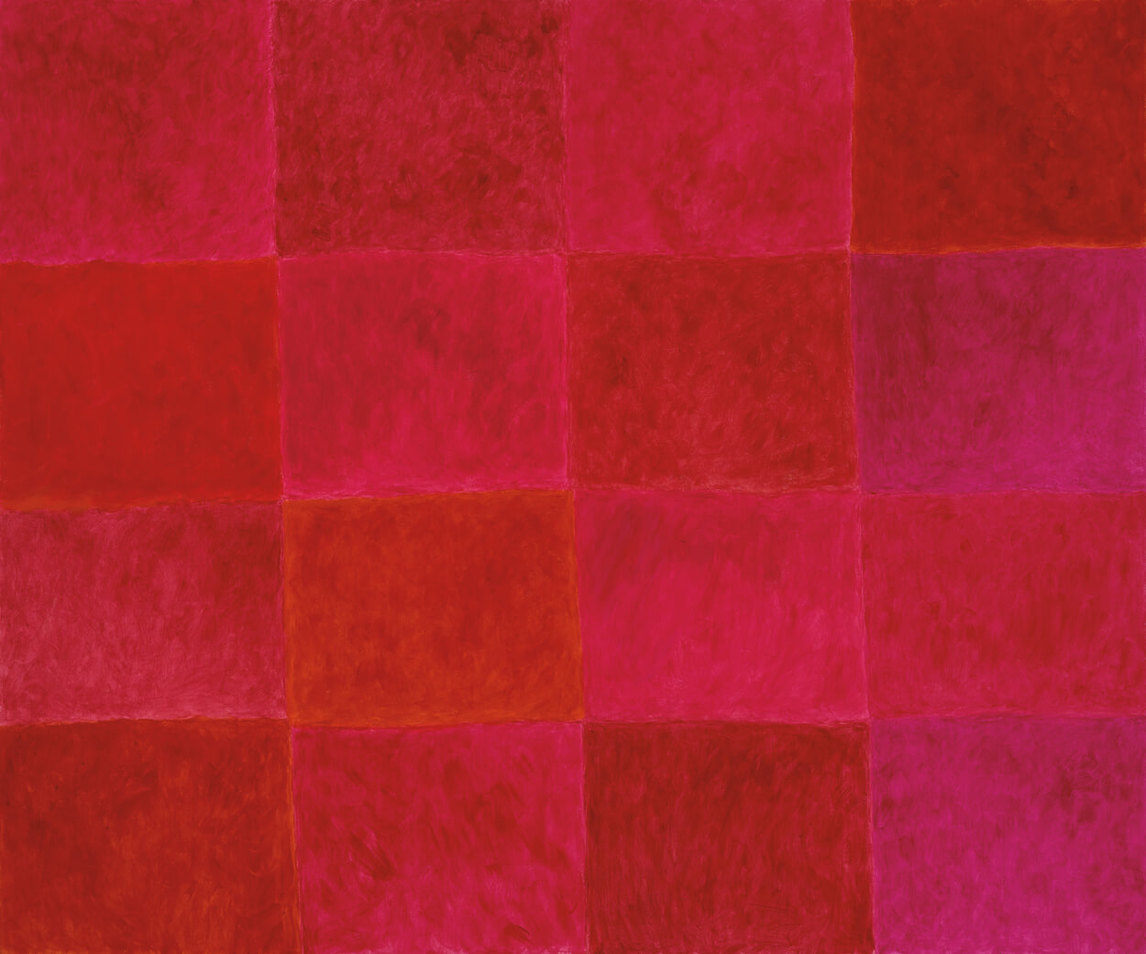

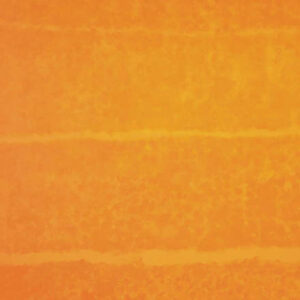

These varied mediums call for different skills and techniques, which Sullivan honed, demonstrating dedication, focus, and boundless creativity. But clear guiding threads weave in and out of all of her work and show the growth of the artist over the span of her career. Sullivan’s Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige), 1948, for example, an improvised piece that allowed the dancer’s body to follow its impulses and freely express emotions, was clearly influenced by the discussions about automatism and creative freedom she had with Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) in the early 1940s. Her sculptures, whether they were assembled from steel, as was Callooh Callay, 1967, or moulded from Plexiglas, as was Of One (De une), 1968–69, seem to defy gravity, giving an impression of movement and weightlessness, no doubt indebted to Sullivan’s dance training and her understanding of movement in three-dimensional space. Sullivan’s conceptual work, and particularly her walking performances such as Walk between the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Fine Arts (Promenade entre le Musée d’art contemporain et le Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal), 1970, brings together body motion and a sculptural sensibility, attuned to the environment in which it unfolds. And her later paintings draw from all the artistic experiments she conducted throughout her career: the Tondo paintings from 1980–82 incorporate three-dimensional elements, monochromes from the Homages (Hommages) series made in 2002–03 rely on improvisation and record the gestures the artist makes with her body as she paints, while the Only Red series of 2016 draws from the methods of conceptual art; Sullivan gave herself a simple task that she repeated, with only slight variations from one work to the next, making each with a variety of red paints.

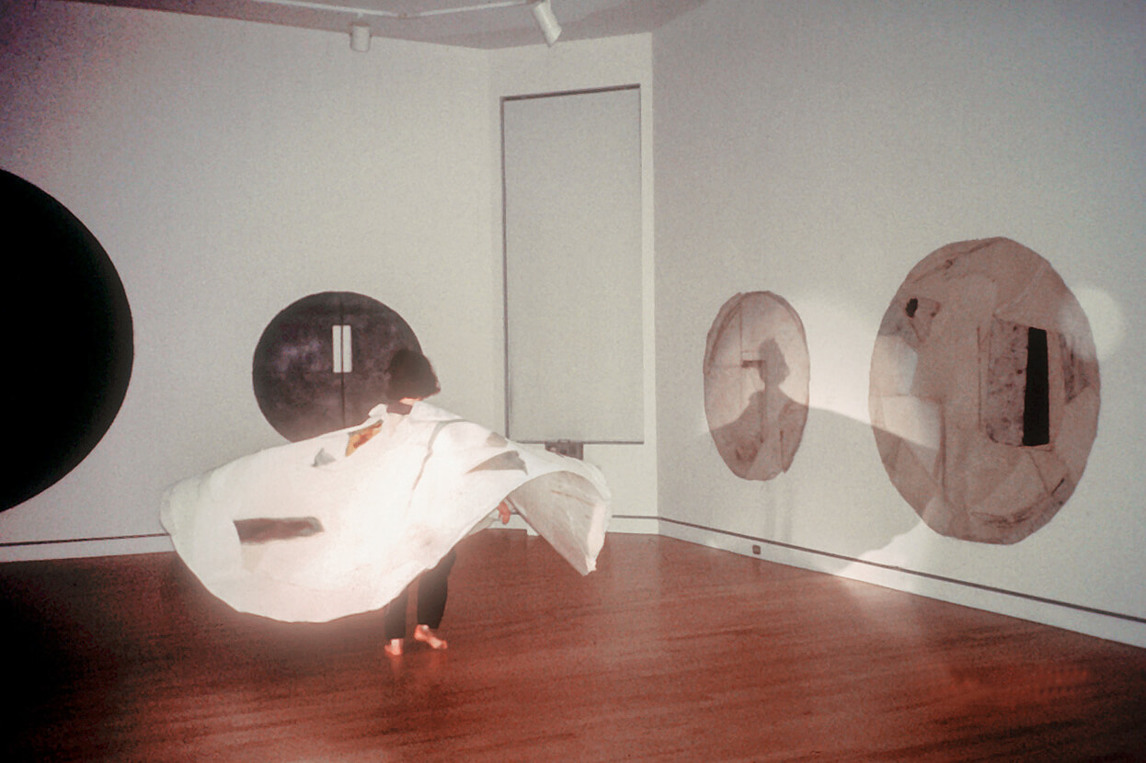

In a few instances, Sullivan’s ease in crossing from one medium to another translated into interdisciplinarity; in these cases she made works that do not belong to dance, sculpture, conceptual art, or painting but rather create entirely new relations between them. She and Jeanne Renaud (b. 1928) were indeed at the leading edge of interdisciplinary work when, in the 1948 Ross House recital that featured eight choreographies by Sullivan and Renaud, they brought together dance, music, poetry, and the visual arts in ways that had rarely been seen before. They integrated music by Pierre Mercure, Duke Ellington, and Edith Piaf, with costumes and set designs by Automatiste painter Jean-Paul Mousseau (1927–1991) and Surrealist poetry by Refus global signatory Thérèse Renaud (1927–2005), read during the performance by Automatiste poet Claude Gauvreau (1925–1971). In 1979, in a Happening titled Accumulation that took place at the Ferrare museum in Italy, Sullivan moved stones that blocked a door and arranged them into a large circle while Paul-André Fortier, Daniel Soulières, Daniel Léveillé, Michèle Febvre, and Ginette Laurin were dancing in it. Laurin performed Daedalus (Dédale), a choreography first danced by Sullivan at the Ross House recital in 1948. And in 1993, she choreographed I Speak (Je parle) for a retrospective exhibition titled Françoise Sullivan at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, during which Ginette Boutin, clothed in one of Sullivan’s Tondo paintings, swirled, with the canvas rising and falling according to the speed of her rotation. As the dancer spun, she called out, “I speak the pine, the fir, the poplar … I speak the path of dawn … I speak the hand of the wind … I speak the night made with the raven …” and so on. These unclassifiable works are all fusions of visual art, dance, and poetry, and they encourage viewers to let go of their expectations of art and its time-honoured disciplinary traditions.

While art critics did not pay as much attention to these practices as they did to more established genres such as painting, Sullivan’s innovative approach to art making and her readiness to cross disciplinary borders has nevertheless influenced a new generation of Canadian artists who gained knowledge about her work through photographic documentation, the texts she wrote, and retrospective exhibitions of her work. Among these are painter Monique Régimbald-Zeiber (b. 1947), who feels a particular kinship with Sullivan’s multifarious practice; painter Lise Boisseau (b. 1956), who created a series of ink drawings inspired by Sullivan’s choreographies; dancer and visual artist Lise Gagnon (b. 1962), whose video titled Elegy: The Dance in the Snow (Élégie: La danse dans la neige), 2015, constitutes an homage to Sullivan; and performance and installation artist Luis Jacob (b. 1970), who also revisited Sullivan’s Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige), 1948, in a very personal manner in his 2007 multi-channel video installation, A Dance for Those of Us Whose Hearts Have Turned to Ice, presented at Documenta 12 in Kassel, Germany.

Unleashing Creative Forces

An interest in the art of non-European peoples was prevalent in European and North American artistic circles during the first half of the twentieth century, and it influenced the work of Cubists, Expressionists, Surrealists, and many others. The word “primitivism” was used as a catch-all term for the appropriation by formally trained artists of motifs, techniques, or composition from African, Asian, or other non-European artistic traditions. It implied that these artists tapped into primal energy and emotions, unmediated by modern society or by their own training and culture.

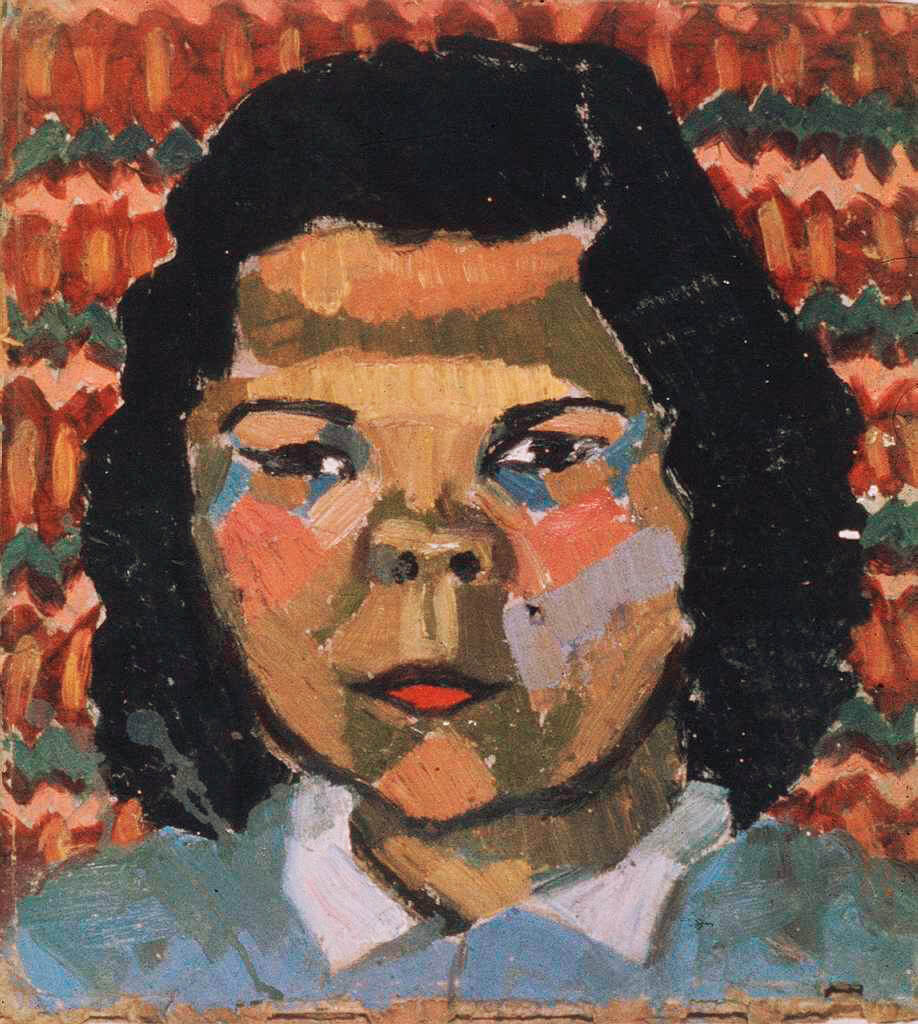

Sullivan acquainted herself with this trend while studying at the École des beaux-arts in the early 1940s. Dissatisfied with the academic training she was receiving, she became interested in French modernist painting, in particular that of Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and the Fauves, who looked to African and Japanese art for inspiration. In some of her earliest paintings, Amerindian Head I (Tête amérindienne I), 1941, and Amerindian Head II (Tête amérindienne II), 1941, Sullivan borrowed their coarse brush stroke and unconventional use of colour to depict her subjects in a way that emphasized their Otherness.

Automatism, influenced by Freudian conceptions of free association and of the unconscious, was meant to unleash subjectivity and allow artists to reach toward a truer, original self. Sullivan’s grasp of theories of the unconscious as they relate to the “primitive” further developed through her contact with Franziska Boas (1902–1988), with whom Sullivan studied dance in New York during the 1940s. Boas organized anthropology seminars for her students, to encourage them to learn more about dance in different cultures. She also introduced them to non-European music as she beat out rhythms on the instruments she had collected from around the world. In this context, Sullivan and her cohort read the writings of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung. Jung was extremely influential in New York artistic circles at that time, in particular for his understanding of archetypes—universal, archaic patterns and images that derive from the collective unconscious. Jungian psychoanalysis marked the production of Abstract Expressionist painters such as Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) and Mark Rothko (1903–1970), as well as that of dancers and choreographers such as Boas, Martha Graham (1894–1991), Pearl Primus (1919–1994), and Merce Cunningham (1919–2009), who in turn became models for Sullivan. As she recalled, “We thought that studying ‘primitive people’ could help find new things to say as a choreographer.”

In Sullivan’s dance work, improvisation served the purpose of tapping into the collective unconscious, and choreographies such as Daedalus (Dédale), 1948, Hierophany (Hiérophanie), 1978, and Labyrinth (Labyrinthe), 1981, culminate in dancers frenetically spiralling in a way that echoes ritual dancing. The spiral is an archetype, in Jungian terms. It is a symbol of perpetual return to the origins and transcending of self. It reappears in various media throughout Sullivan’s career, sometimes modified into a circle, a coil, a labyrinth, or a cycle. It is most explicitly seen in her spiral Plexiglas sculptures, the circular accumulations of stone she created in Greece in the 1970s, her 1981 print series titled Labyrinth, and her round paintings of the Cretan Cycle, 1983–85, populated with mythological figures inspired by her visits to archaeological sites.

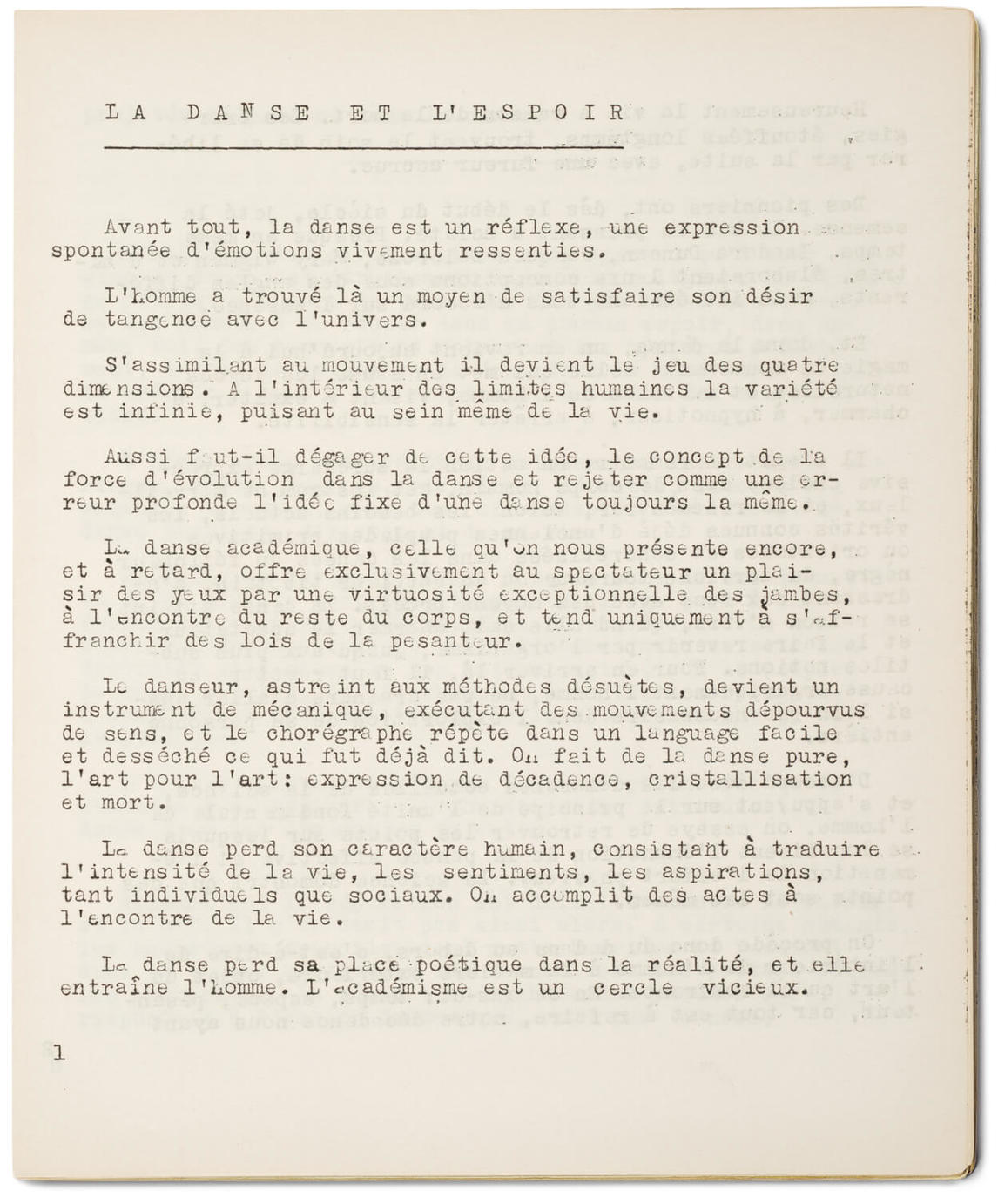

In her 1948 essay “La danse et l’espoir” (“Dance and Hope”), Sullivan reflects on how the primal energy that ancient and Indigenous cultures valued could give art a new breath and fuel a challenge to established rules, both of the academy and of society. But Sullivan also understood the futility of reproducing expressive forms created by other societies. For her, it seemed necessary to invent new ones, ones capable of channelling creative energy in a way that was intelligible to a contemporary public. As she explained: “It must be clearly understood that the dancer does not choose a type of dance; this is not a question of ethnology, but of contemporary life. Art can only flourish if it grows from problems which concern the age, and is always pushed in the direction of the unknown.”

Manifestos and Writings about Art

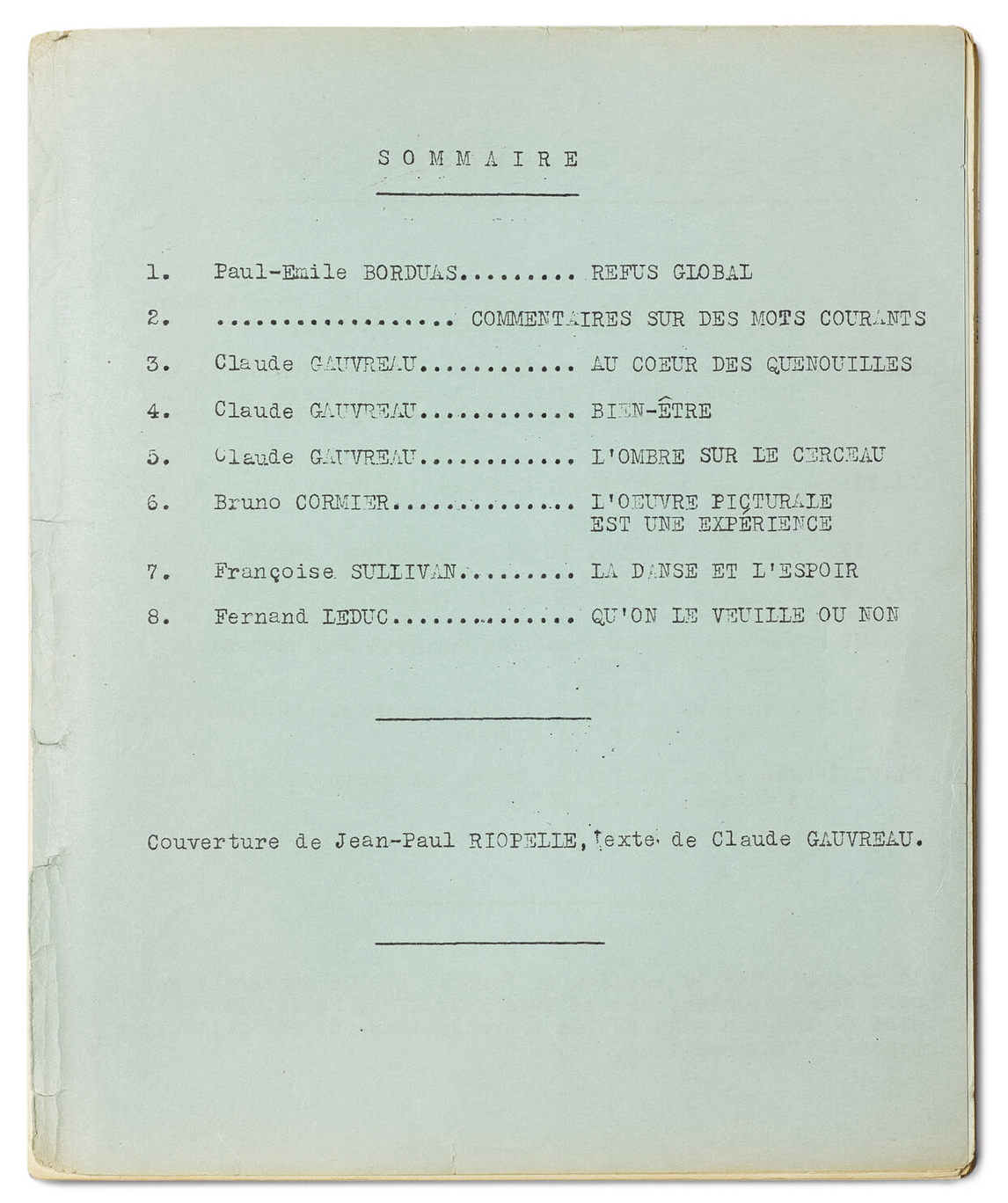

Several artists’ manifestos were written in Quebec in the twentieth century. The most famous and controversial is without doubt Refus global (Total Refusal), launched in Montreal on August 9, 1948. Sixteen artists known as the Automatistes signed the manifesto that completely rejected the social, artistic, and psychological values and norms of Quebec society and proposed that social and individual emancipation could be attained through creativity and openness to the unconscious: “Let those moved by the spirit of this adventure join us. Within a foreseeable future, men will cast off their useless chains. They will realize their full, individual potential according to the unpredictable, necessary order of spontaneity—in splendid anarchy.”

Refus global caused an uproar in Quebec society. Paul-Émile Borduas, leader of the Automatistes, lost his teaching job and several of the other signatories left the country to pursue their careers elsewhere. It is now considered a pivotal text that contributed significantly to how Quebec entered cultural and social modernity.

Françoise Sullivan did more than sign Refus global; she contributed a text to be published with it. “La danse et l’espoir” (“Dance and Hope”) explains her conception of modern dance, and her belief that it can inspire personal freedom and awareness of one’s environment. Throughout her career, Sullivan published writings that described her work, her influences, and her understanding of the role art could play in contemporary society. In her first, “La peinture féminine” (1943), she discusses recent and contemporary painting by women; in “Je précise” (1978), she reflects on her earlier dance work; in “Salue Zarathoustra” (2001), she insists on the individual nature of the artistic process. She integrated short texts and poems into exhibition catalogues and made others available during exhibitions. Sullivan also spoke at public events. A talk on the subject of conceptual practices she gave at the Université du Québec in April 1975, during which she explained why contemporary artists were then turning away from the making of objects to better focus on thought process, is now considered a key moment in the history of Quebec art.

As art historian Rose-Marie Arbour has pointed out, writing by female artists, particularly those working in non-traditional media, played a crucial role in the early twentieth century. This is because art criticism tended to favour painting, and the work of male artists. Without Sullivan’s writings, many of her ideas and the significance of her earlier works would have been lost. But for Sullivan, writing was not simply a way to document or explain her art practice; it was another way of exploring creativity and communicating.

Documenting and Recreating Artworks

When, in 1947, Françoise Sullivan set out to create an improvised dance cycle based on the seasons, she knew she needed to innovate by documenting it in a new way. Traditional notation systems used for dance choreography were not appropriate for improvisation, and she wanted to leave a record of the ephemeral event that was to occur without an audience.

Summer (L’été) was danced at Les Escoumins in the Côte-Nord region of Quebec in the summer of 1947. It was captured by Sullivan’s mother with a 16mm camera, a technology that had been around since the mid-1920s but had not yet made its way into the art world in a substantial way. Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige) was performed in February 1948 outside the town of Otterburn Park, southeast of Montreal. Sullivan had arranged with Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002) to film the event, using the Sullivan family camera. It was only by chance that Maurice Perron (1924–1999) happened to be there. Perron had studied at the École du meuble with Riopelle and was part of the Automatiste group, whose members he photographed frequently as they enjoyed social events or worked in their studios. Standing shoulder to shoulder with Riopelle, he took stills of the dance. Unfortunately, the film reels shot by Sullivan’s mother and by Riopelle have been lost. Perron’s beautiful photographs remain the only record.

Nearly thirty years later, Sullivan chose seventeen images shot by Perron in 1948 to represent Dance in the Snow in a 1978 solo exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and for a limited-edition loose-leaf portfolio published for the occasion. Aware of how documentation can influence reception and the historical understanding of art, she selected the pictures for how they synthesized the energy and flow of the dance, arranging them to reflect the sequence of movements as they had occurred. Perron exhibited the photographs several times, changing their order and adding more original stills to the series. This difference in how Sullivan and Perron presented the photographs highlights the double role that the images play, as documentation of Sullivan’s performance and as artworks in their own right.

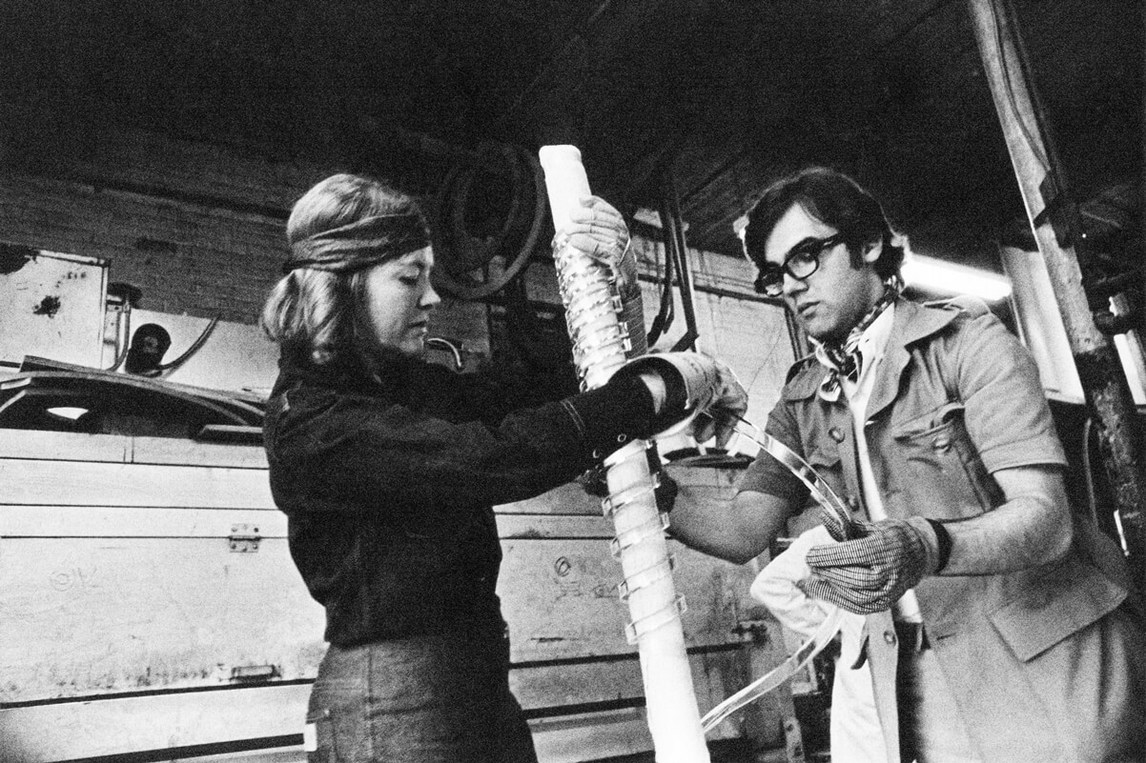

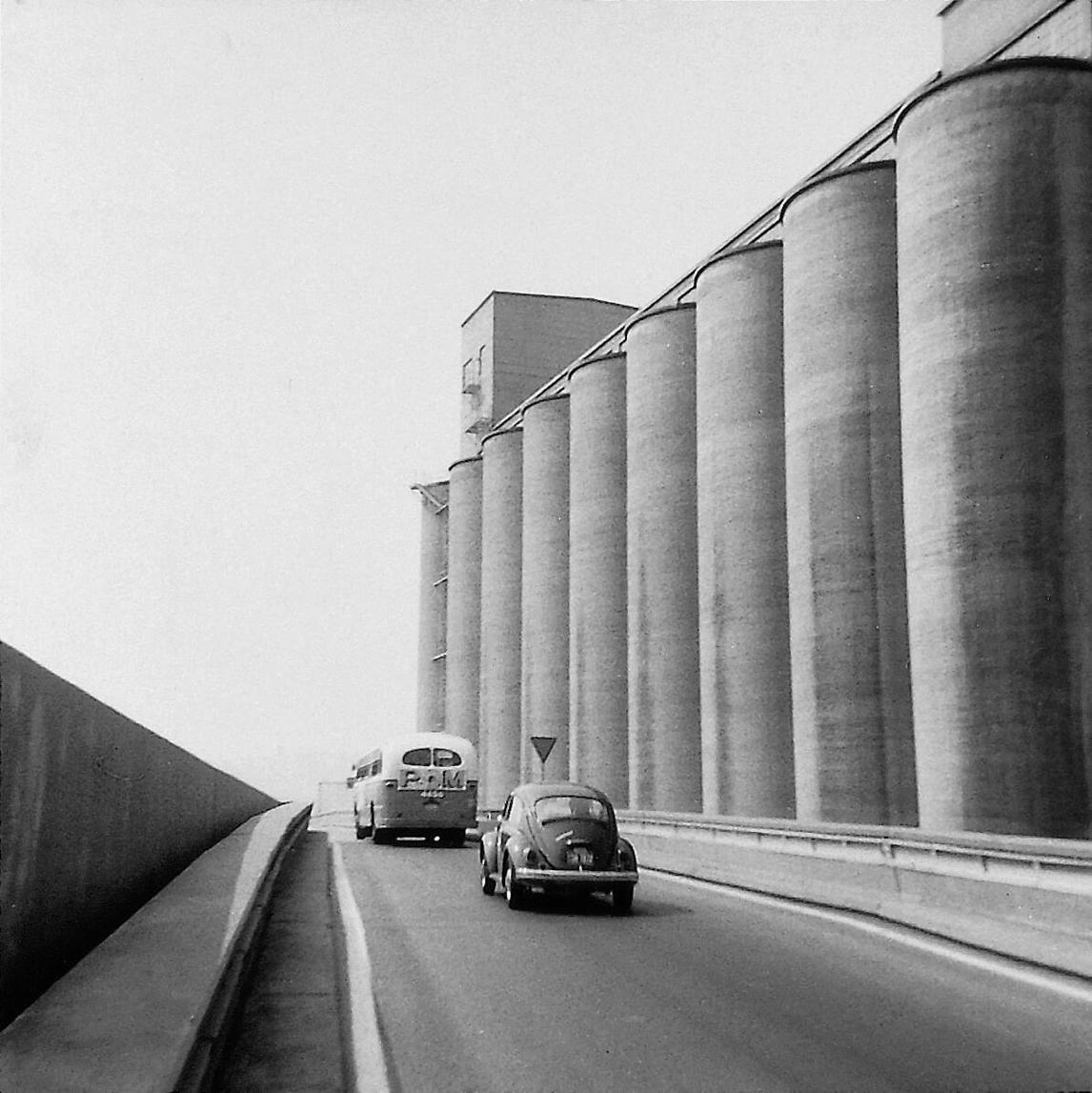

Following this early experiment, Sullivan made it a habit to record her work. She documented her point of view with a camera as she crossed the city in a performance titled Walk between the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Fine Arts (Promenade entre le Musée d’art contemporain et le Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal), 1970, and, when she didn’t do it herself, she asked friends to film and take pictures of her 1970s Happenings that resulted in accumulations of stone and other found materials. The stills were later exhibited, and some found their way into museum collections. The artist’s careful selection of the documents to be shown allowed her to control her image herself and manage, to a certain degree, how her works would be received by critics and by the public. In the second half of the twentieth century, many Canadian artists, such as Tanya Mars (b. 1948), Istvan Kantor (b. 1949), and Johanna Householder (b. 1949), experimenting with time-based or conceptual art practices, took up the same habit.

The documentation of Sullivan’s performances is of critical importance to her body of work as a whole, since it often constituted the only experience the public could have of a piece, and sometimes generated subsequent artworks. The photographs taken in 1973, for example, to record Walk among Oil Refineries (Promenade parmi les raffineries de pétrole), found their way a year later into a 1974 photomontage titled Encounter with Archaic Apollo (Rencontre avec Apollon archaïque). But the clearest case in point is The Seasons of Sullivan (Les saisons Sullivan), 2007, a film with four parts accompanied by a limited-edition photographic portfolio. The project, initiated by Louise Déry, director of the Galerie de l’UQAM, was meant to complete and give a second life to Sullivan’s ambitious 1947–48 dance cycle. Sullivan had performed summer and winter, but the planned improvisations on the themes of fall and spring never occurred. Sixty years later, working from memory and from Perron’s photographs, she choreographed all four dances and hired dancers to perform them. These were in turn photographed by Marion Landry (b. 1974) and documented in four short films, co-directed by painter and videographer Mario Côté (b. 1954) and Sullivan, that are also artworks in their own rights.

If some spontaneity was necessarily lost in the 2007 recreation, what was truly important for Sullivan was that the spirit of the piece, the relationship between the dancer and her environment, be as close as possible to the original. The preservation through film of Sullivan’s dance work is an ongoing project. In 2008 Mario Côté recreated Daedalus (Dédale), 1948, and, in 2015 Black and Tan, 1948, interpreted by Ginette Boutin. The reactualizations of the two choreographies created and performed by Sullivan in 1948 in the recital she organized with Jeanne Renaud at Ross House were based on photographs, choreographic notes, and discussions with Sullivan, who worked with the dancers.

If, through filmed re-enactment, these works can now be appreciated, Dance in the Snow was given a new lease on life when Luis Jacob (b. 1970) appropriated it in 2007 as the inspiration for a multi-channel video installation. A Dance for Those of Us Whose Hearts Have Turned to Ice pays homage to the seminal 1948 performance in a way that also allows it to speak to gender, cultural diversity, and other artistic concerns that are crucial to many artists of Jacob’s generation.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements