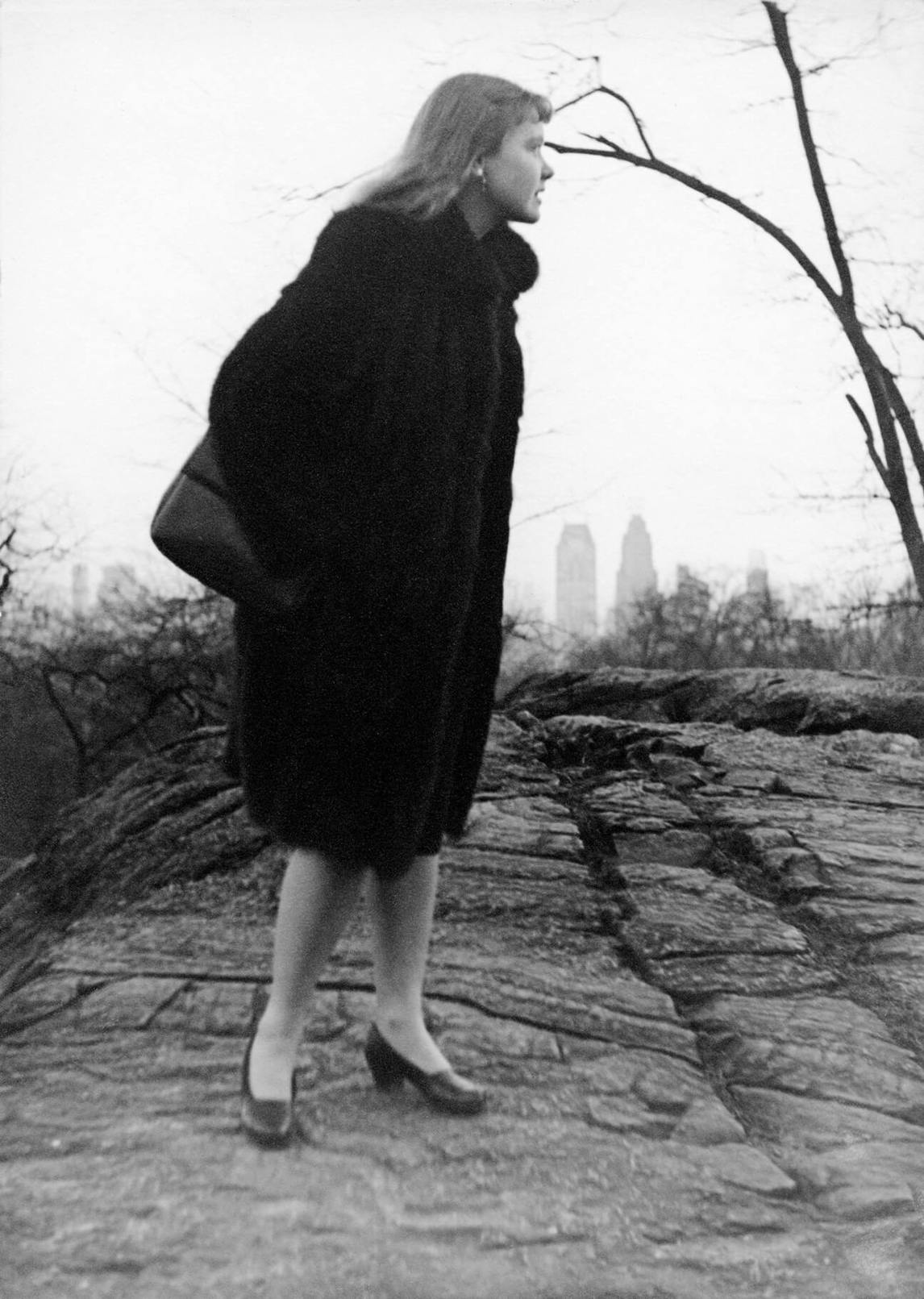

Françoise Sullivan (b. 1923) is best known as a pioneering figure of modern dance and one of the signatories of the 1948 manifesto Refus global (Total Refusal). But Sullivan also produced an extensive body of performance and installation works, photographs, sculptures, and paintings that coalesce around issues of primal energy, movement, improvisation, and art’s relationship to its environment. With a career that spans more than seventy years, Sullivan is one of the most versatile and enduring artists of her generation.

Early Life

Born on June 10, 1923, in Montreal, Françoise Sullivan was the youngest of five children and the only daughter of Corinne (Bourgouin) and John A. Sullivan. Sullivan’s father practised law and occupied numerous political posts throughout his career.

Sullivan wanted to be an artist from an early age. Her parents appreciated art and encouraged their daughter in her pursuits. Her father especially loved poetry and wrote the occasional poem. Her mother enrolled her from the age of eight in various classes: dance, drawing, music, and acting. She was passionate about dance and started creating choreography in her early teens, putting on recitals for the neighbourhood children.

At that time, pursuing the arts was seen as a respectable pastime for young women, one that provided them with a cultural education. She had begun to develop friends with whom she exchanged ideas on intellectual and artistic subjects: Sullivan met Pierre Gauvreau (1922–2011) and Bruno Cormier (1919–1991). She considered them her first intellectual encounter. Her parents were familiar with art and did not object when she expressed the wish, at the age of sixteen, to register at the École des beaux-arts in 1940.

At the École

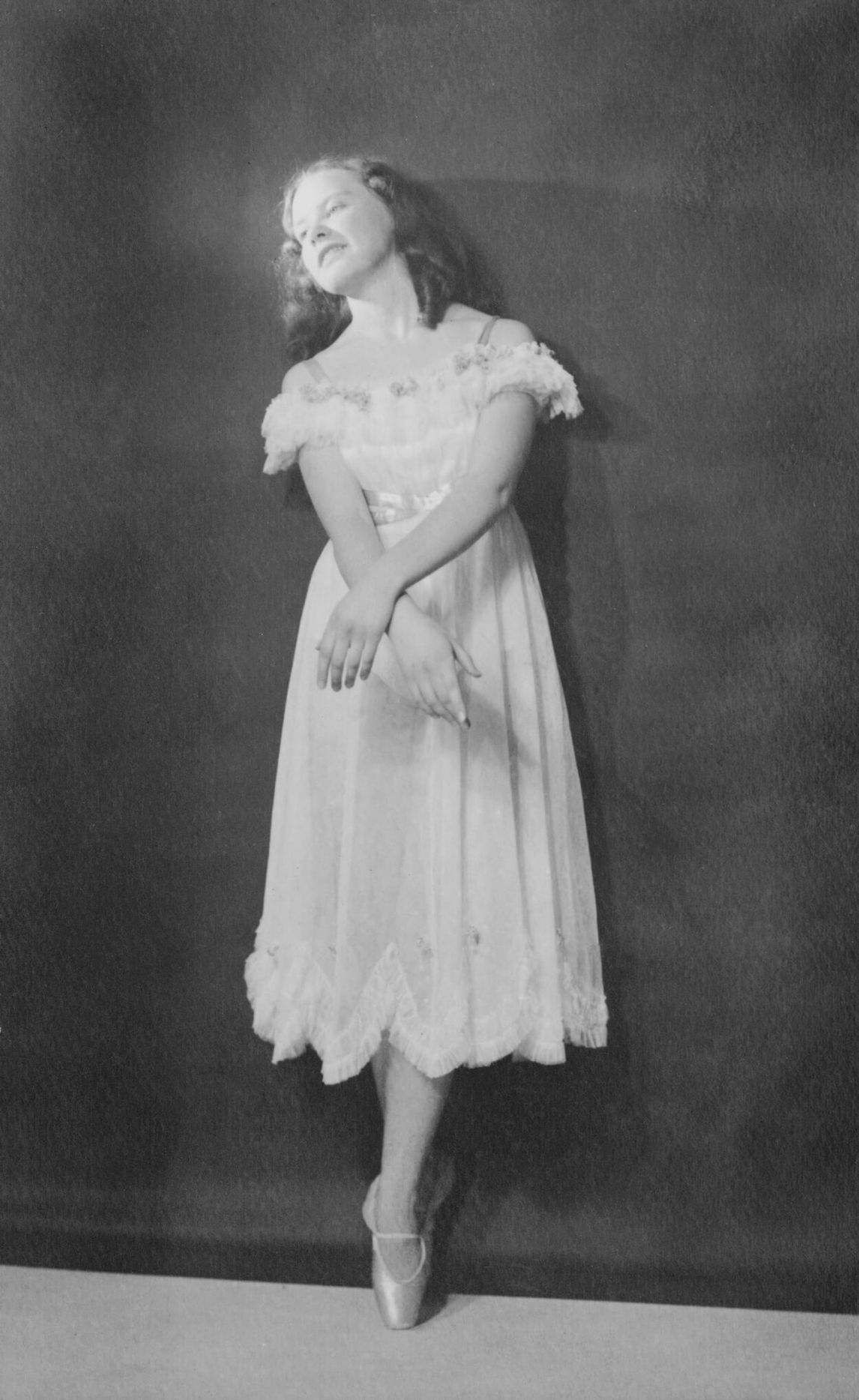

At a time when higher education was not accessible to most women, the École des beaux-arts accepted both male and female students, pending an entry exam, and was free. Sullivan registered in drawing and painting classes, and she excelled. She won the school’s first prize for drawing in 1941, the first prize for painting in 1943, and the Maurice Cullen prize for painting, also in 1943. Throughout this time, she continued to dance, training with Gérald Crevier (1912–1993), a classical and tap dancer who went on to found Quebec’s first classical ballet company in 1948.

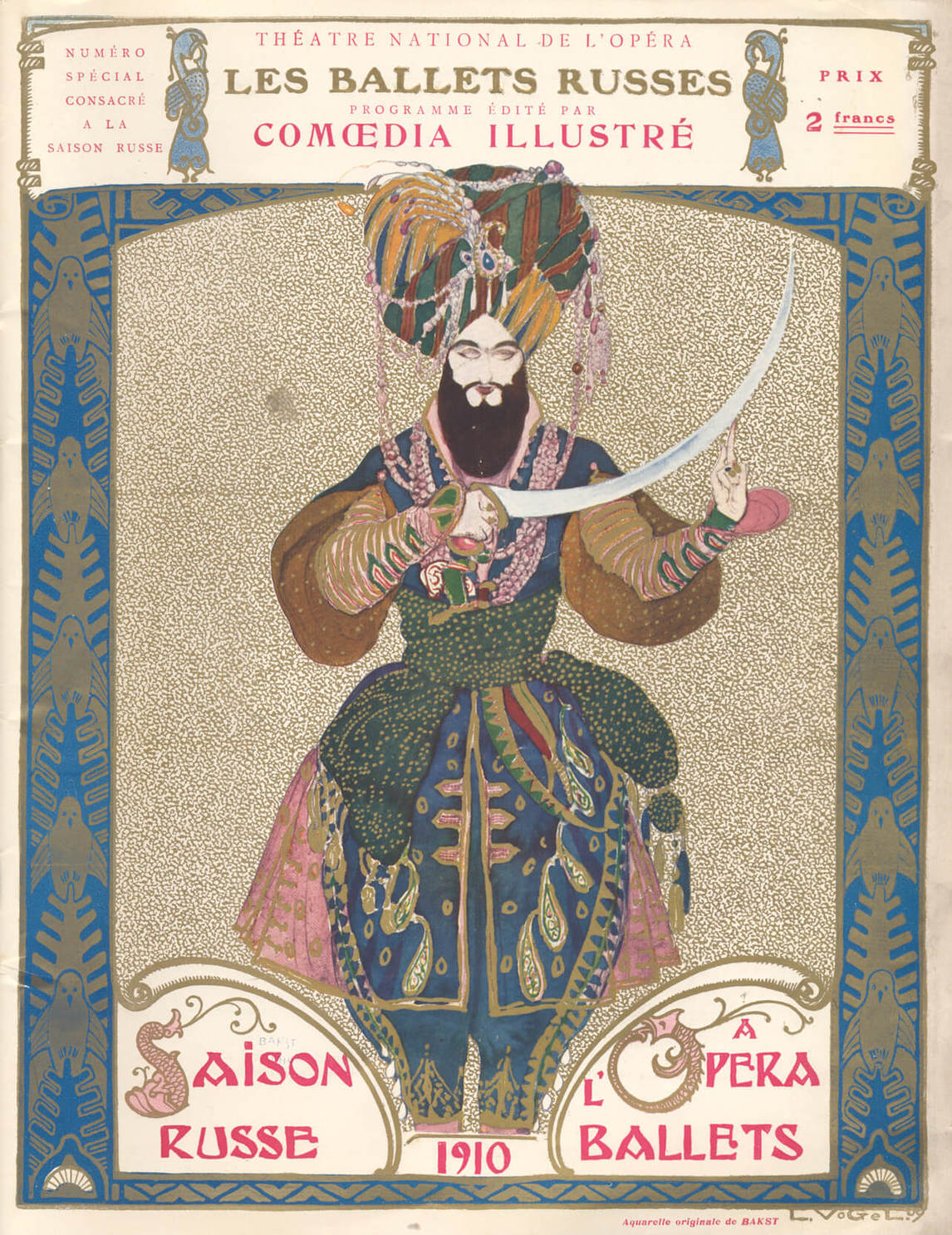

The pedagogical program at the École des beaux-arts, like those of traditional European academies, was based on drawing from classical plaster moulds and the study of the human figure. Imitation was key, and creativity was frowned upon. But Sullivan was curious about new trends in art and complemented her education by studying reproductions of the works of modern artists such as Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Marc Chagall (1887–1985), and Henri Matisse (1869–1954). She read the poetry of William Blake (1757–1827), Émile Nelligan (1879–1941), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891), and William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), whose interest in dreams and myth provided their works with an aura of disreputability in Catholic Quebec. With school friends Louise Renaud (b. 1922), Fernand Leduc (1916–2014), and Pierre Gauvreau, she also listened to the music of avant-garde composers Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) and Edgard Varèse (1883–1965), and attended the lavish performances that the Ballets Russes gave at His Majesty’s Theatre in Montreal.

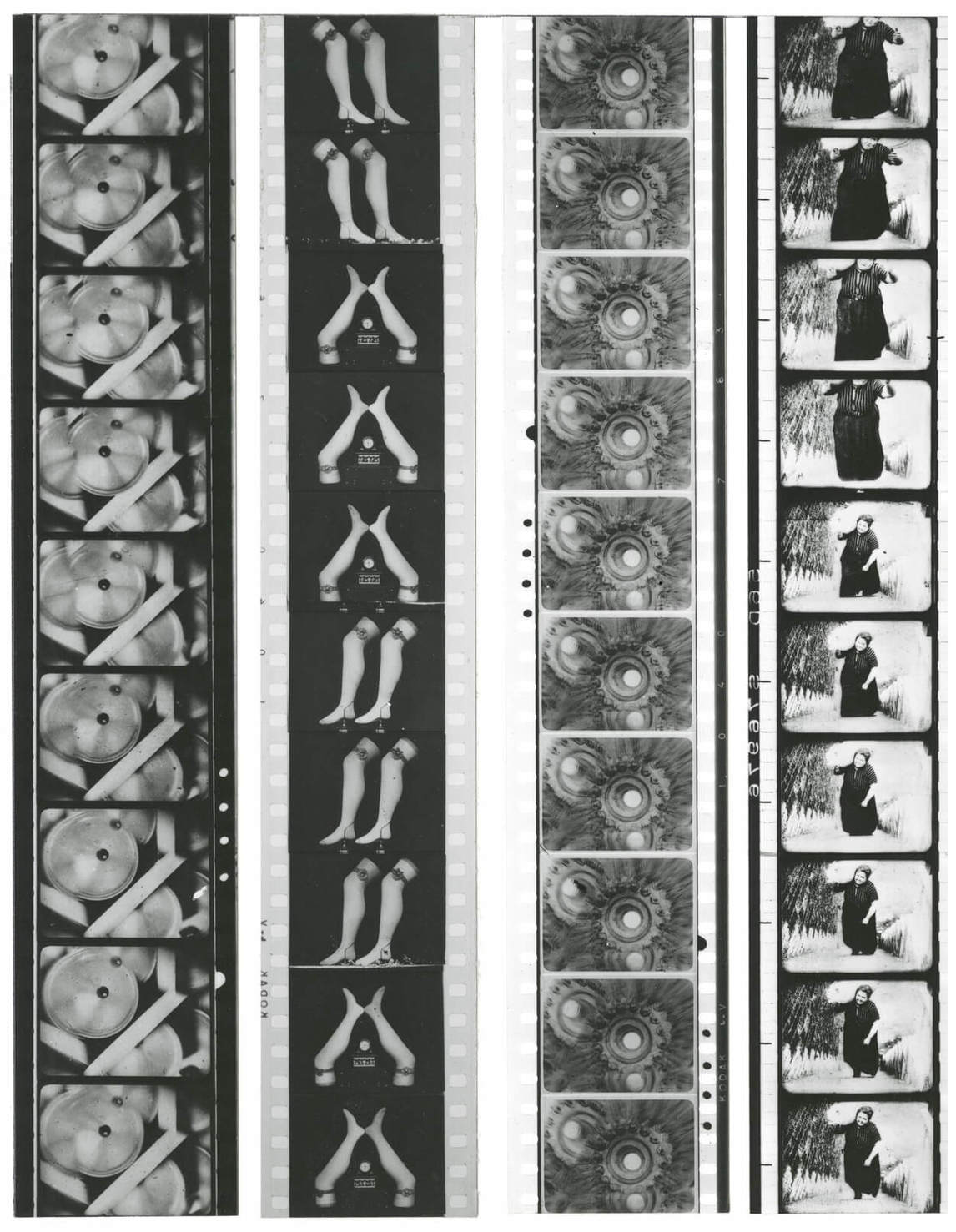

Although the Second World War had begun in 1939 and wartime policies often meant rationing and restrictions on the home front, the cultural scene in Montreal was becoming more dynamic than ever. Painters such as John Lyman (1886–1967) and Alfred Pellan (1906–1988) had recently returned to the city after years spent abroad, where they had participated in movements such as Fauvism, Cubism, and Surrealism. They advocated for the development of modern art in Quebec through art criticism, lecture series, and exhibitions of modern European art. Sullivan sought out these events: in 1939 she saw the Art of Our Day exhibition organized by Lyman through the Contemporary Arts Society, which included works by Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), André Derain (1880–1954), and Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920); and in 1941 she met and befriended French painter Fernand Léger (1881–1955) at a showing of his 1924 experimental film Mechanical Ballet (Ballet mécanique).

Borduas and the Automatistes

In 1941 Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) saw one of Pierre Gauvreau’s paintings at a student exhibition. Impressed with the work, Borduas invited the young painter to his studio. Sullivan accompanied her friend, along with Louise Renaud and Fernand Leduc. In the years that followed, the group expanded to include several students from Montreal’s École du meuble, where Borduas was teaching. They met every two weeks on Tuesday evenings in Borduas’s studio on Mentana Street in Montreal, and later in Fernand Leduc’s and Jean-Paul Mousseau’s (1927–1991) studios. Starting in 1943 the group also made periodic outings to the town of Saint-Hilaire, where Borduas moved with his family. During these meetings, they talked about art and the creative process, and they discussed the works of Pierre Mabille, whose writings on wonder and the imaginary, at the crossroads of anthropology, sociology, and medicine, had a profound influence on Sullivan. Borduas rejected the traditionalism of academic art, with its conventional themes and style, and valued above all creativity, spontaneity, and free expression.

Quebec was then entrenched in what has become known as La Grande Noirceur (The Great Darkness), a period of its history characterized by conservative politics, firm religious dogma, patriarchal values, and censorship. Concerned for their society, the group also discussed philosophy, politics, religion, and psychoanalysis. “It was about breaking with social values. We wanted to overthrow established rules.… We had to strike a blow at our reactionary society.” Because the group was influenced by the French Surrealists’ concept of automatism, which was based on Freudian theories of free association, Borduas and his young friends soon became known as the Automatistes.

The paintings Sullivan made in the early 1940s draw mainly from Fauvism. In works such as Portrait of a Woman (Portrait de femme), about 1945, she explored non-naturalistic use of colour and developed a broad and expressive brush stroke reminiscent of Henri Matisse’s manner. Sullivan’s introduction of subjects that were unconventional at the time, such as Indigenous people in Amerindian Head I (Tête amérindienne I), 1941, and Amerindian Head II (Tête amérindienne II), 1941, testifies to her desire to escape bourgeois social constraints and tap into what was then called “primitivism,” a sensibility that preferred aesthetics and values unspoiled by modernity and Western cultures.

In the following years, Sullivan took a class at the École des beaux-arts with Alfred Pellan, a painter who worked in the wake of Surrealism. With him, she mainly studied figure painting, and with his other students she participated in the Surrealist game of the Exquisite Corpse, which she also practised with members of the Automatiste group. In the spring of 1943, Sullivan participated in her first group exhibition. Les Sagittaires was organized by art critic Maurice Gagnon at Montreal’s Dominion Gallery of Fine Art, founded by Rose Millman in 1941 to showcase and promote Canadian art. The goal of the exhibition was to introduce a new generation of Quebec artists to the Montreal public. Twenty-three painters under the age of thirty participated in the event, which is now recognized as the exhibition that launched Automatism.

Later that year, Sullivan published a short article titled “La peinture féminine” (“Feminine Painting”) in Le Quartier Latin, the Université de Montréal student newspaper. It reflected on the progress made by women in the arts over the previous fifty years in Canada and abroad. It also inaugurated a lifelong writing practice, which Sullivan would use to situate her work within current artistic debates.

Graduating from the École des beaux-arts in 1945 put Sullivan at a crossroads. She had become frustrated with painting; she felt unable to create works that reflected her understanding of Automatism or communicated the energy she put into them. She decided to focus her attention on dance.

The New York Period

Quebec in the early 1940s had no established modern dance schools or troupes. Sullivan’s friend from the École des beaux-arts, Louise Renaud, had moved to New York in the fall of 1943 to study theatre lighting with German director Erwin Piscator (1893–1966). In 1945 Sullivan decided to join her and study modern dance in New York.

Renaud also worked as an au pair in the family of Pierre Matisse, an art dealer and the son of the painter. Matisse’s gallery was a chief meeting place for the Surrealists who had fled Europe and taken refuge in New York after the beginning of the Second World War, and through this connection Sullivan heard stories about artists whose work she had sought out while a Beaux-arts student.

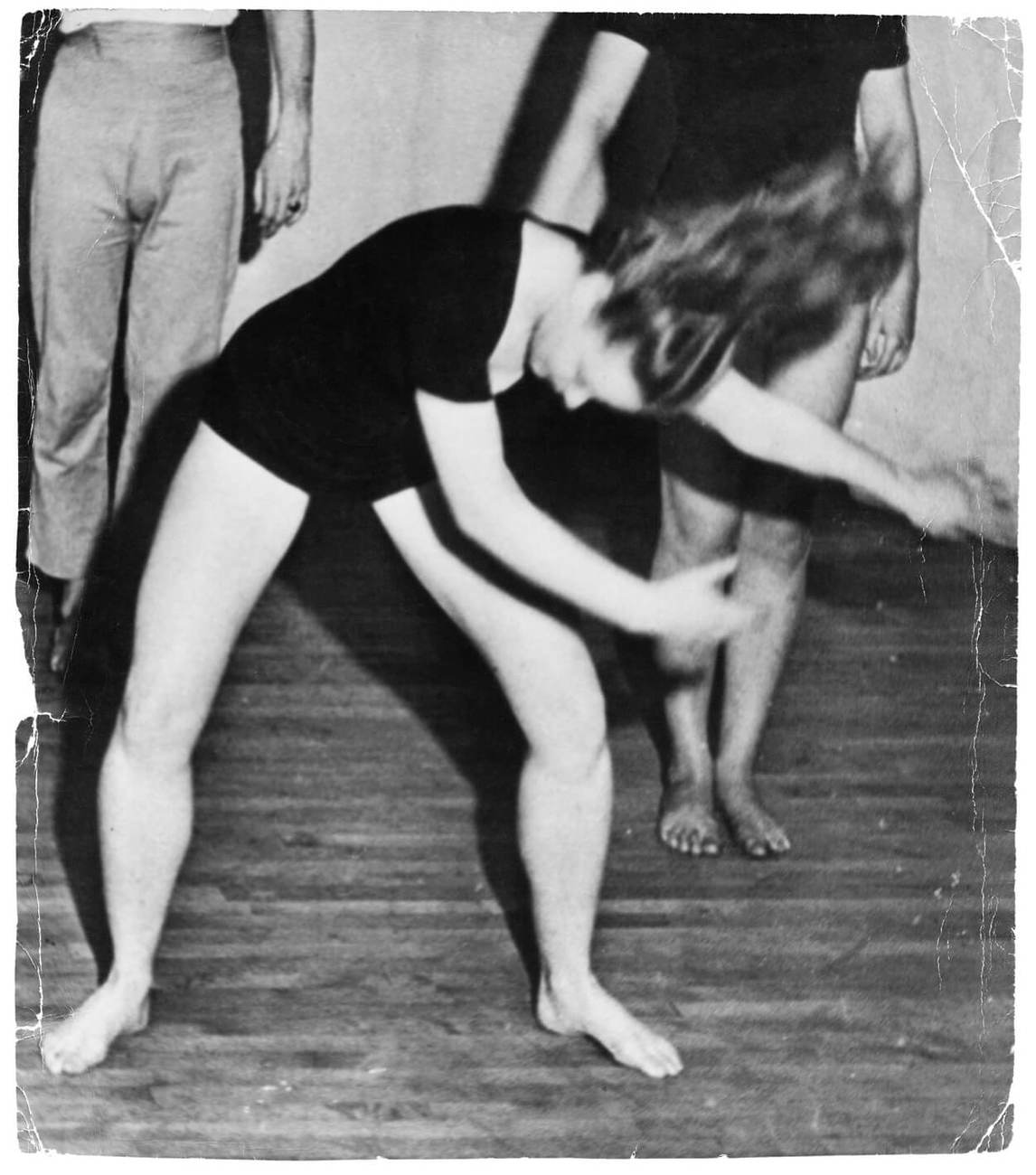

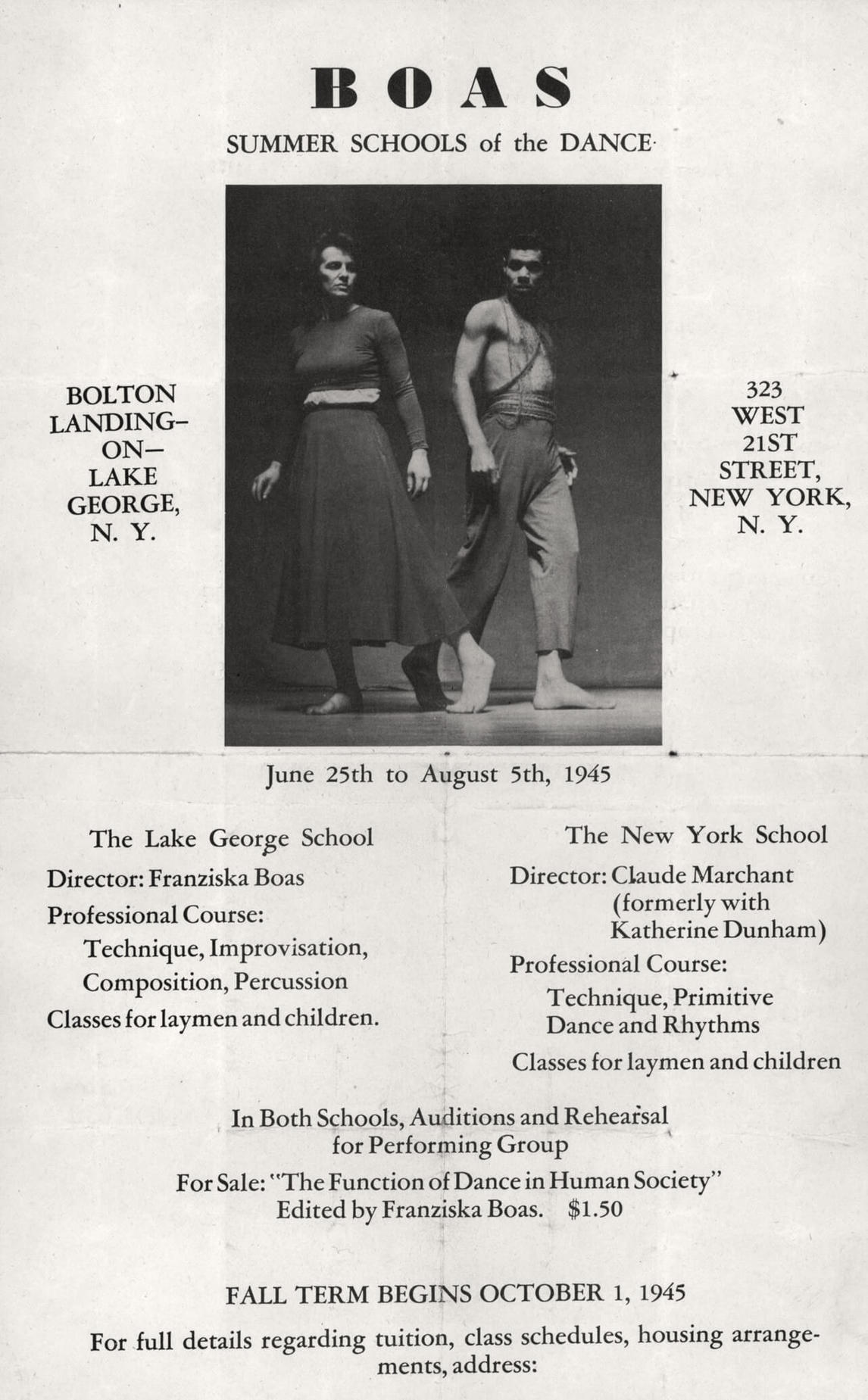

Between the fall of 1945 and the spring of 1947, Sullivan trained with several troupes and teachers, including the New Dance Group, Hanya Holm (1893–1992), Martha Graham (1894–1991), Pearl Primus (1919–1994), Franziska Boas (1902–1988), and La Meri (1899–1988), of whom Boas was certainly the most influential. Boas was the daughter of Prussian-born American anthropologist Franz Boas, who had revolutionized anthropology by challenging the racially biased premises that had shaped the discipline. Like her father, Franziska Boas understood her craft as a means for social activism, and worked throughout her career to facilitate the social integration of marginalized groups through dance.

In this context Sullivan was introduced to non-Western music and dance patterns. She also learned improvisation, which was the backbone of Boas’s pedagogical practice. This approach, designed to free the body and allow it to follow its own impulses, echoed Borduas’s teachings and resonated deeply with Sullivan. During this period she met composer Morton Feldman and the renowned anthropologist Margaret Mead.

The time Sullivan spent in New York was of crucial importance to her own artistic development, but it also had a decisive impact on that of her Montreal colleagues, with whom she kept in contact. The role she, along with Louise Renaud, played in bringing to Quebec recent ideas and reports of the artistic debates happening in New York should not be overlooked; during the Second World War, it was more difficult for her male friends to travel for extended periods, since young men had to remain available for the war effort.

Sullivan was also instrumental in making Quebec art known outside its borders. She organized the Automatistes’ first New York exhibition in January 1946. The exhibition, titled The Borduas Group, was shown at Franziska Boas’s studio. It showcased paintings by Borduas, Pierre Gauvreau, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), Guy Viau (1920–1971), and Fernand Leduc. Sullivan did not include her own works—she had left painting behind in Montreal.

Return to Montreal: Refus global

When Sullivan returned to Montreal in 1947 after completing her training with Boas, she found a society shaken economically and socially by the war and making a return to its prewar ways under the conservative government led by Maurice Duplessis (the period known as La Grande Noirceur [The Great Darkness]) after the short respite of Joseph-Adélard Godbout’s Liberal government between 1939 and 1944. Provincial politics were marked by a foregrounding of Catholic ideology that recalled Quebec’s earlier Survivance period. Continued involvement of the Church in publicly funded French-language schools and hospitals reinforced the idea that Quebec was, above all, a Catholic society, and that the Church had power over the course of people’s lives.

Duplessis’s government took advantage of broad-reaching censorship laws to limit the activities of cultural, religious, and political groups not in line with its policies. Since 1937, Quebec’s Padlock Act (Loi du cadenas) had allowed the provincial government to censor and destroy “subversive” materials deemed to have communist or Bolshevik leanings, with the definitions of “communist,” “Bolshevik,” and “subversive” open to interpretation by those in power. Public discussion of social issues was severely restricted, and individuals and groups opposed to the dominant ideology, such as the Automatistes, struggled to bring their ideas to a public forum.

The relative cultural freedom that had characterized the war period had, however, left its mark. It had allowed progressive social forces to consolidate, in particular with regard to women’s rights, workers’ solidarity, and emancipation from religious dogma. In smaller journals and in open letters in Quebec newspapers (particularly the left-leaning Le Devoir), artists and intellectuals such as the Automatiste writer Claude Gauvreau (1925–1971), the poet and spokesperson of the group, responded to attacks on the art and politics of a growing progressive and modernist movement centred in Montreal.

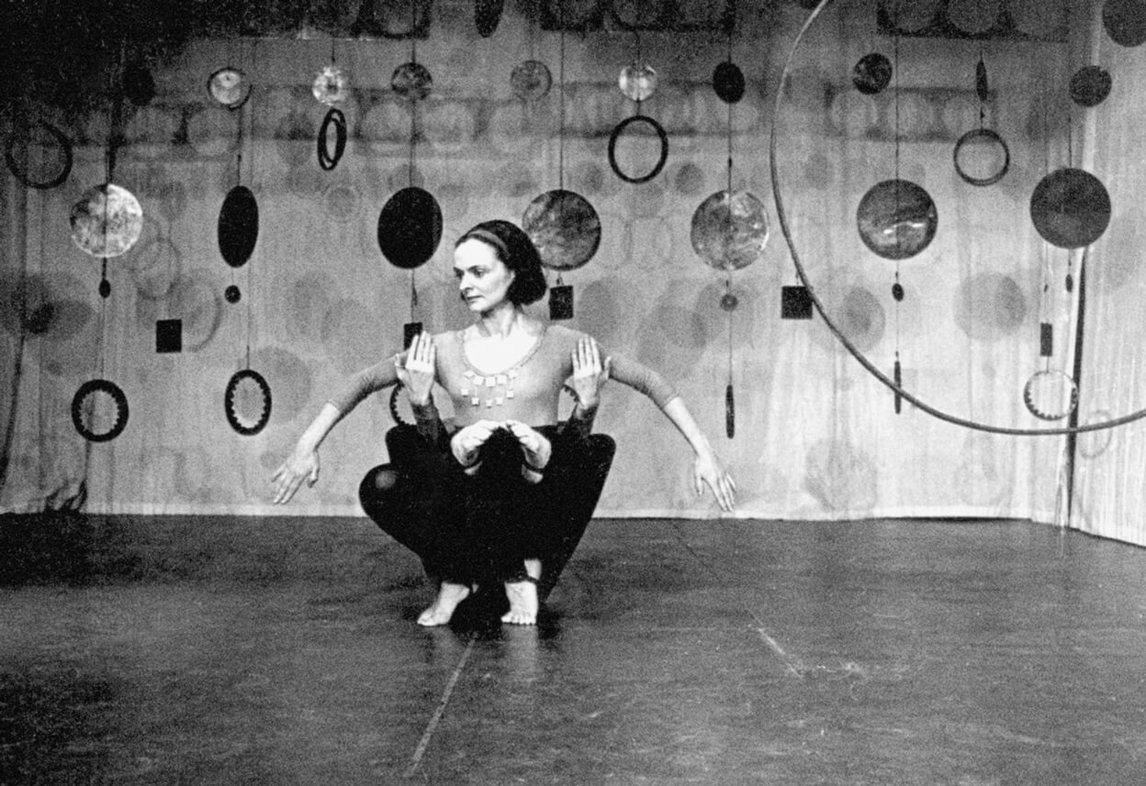

Sullivan set herself up to teach modern dance in 1947. Her classes were strongly influenced by Boas’s methods, and improvisation and openness to other cultures became the cornerstones of Sullivan’s own pedagogy as she gradually shifted from the role of student to that of mentor. In the summer of 1947, she decided to create a cycle of improvised solo dances to be filmed on the theme of the four seasons. The only remaining traces of this work are the haunting photographs taken by Maurice Perron (1924–1999) in February 1948 of Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige).

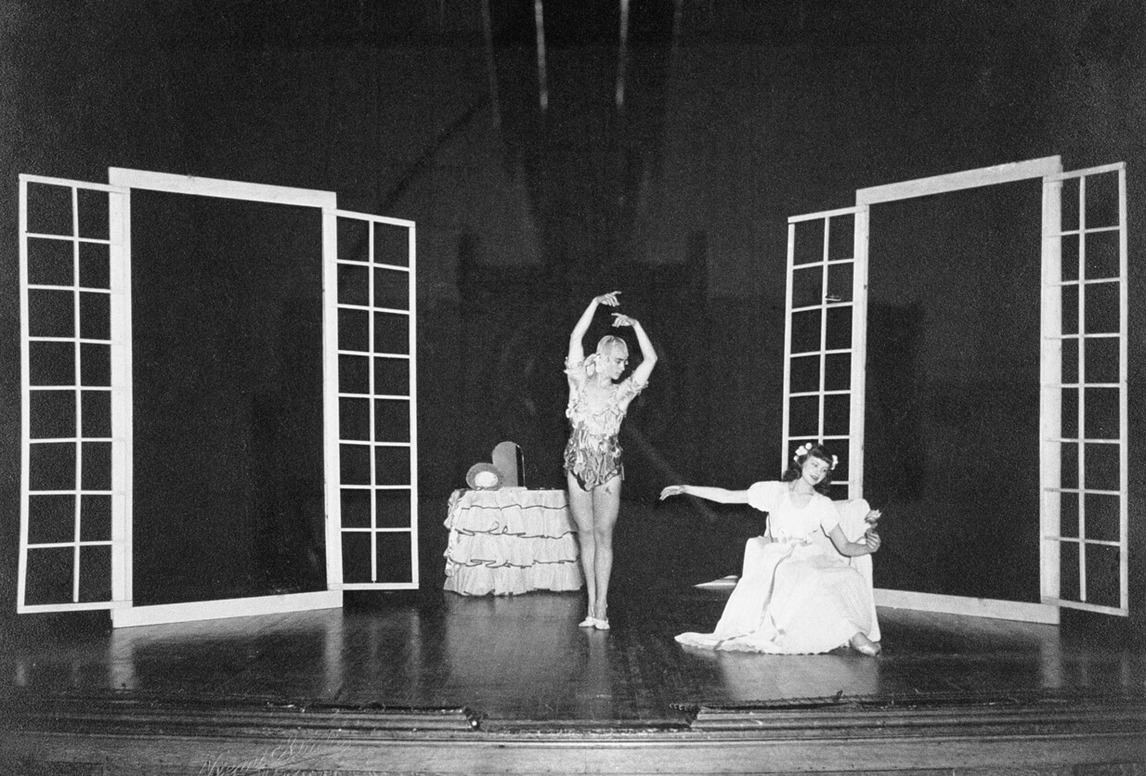

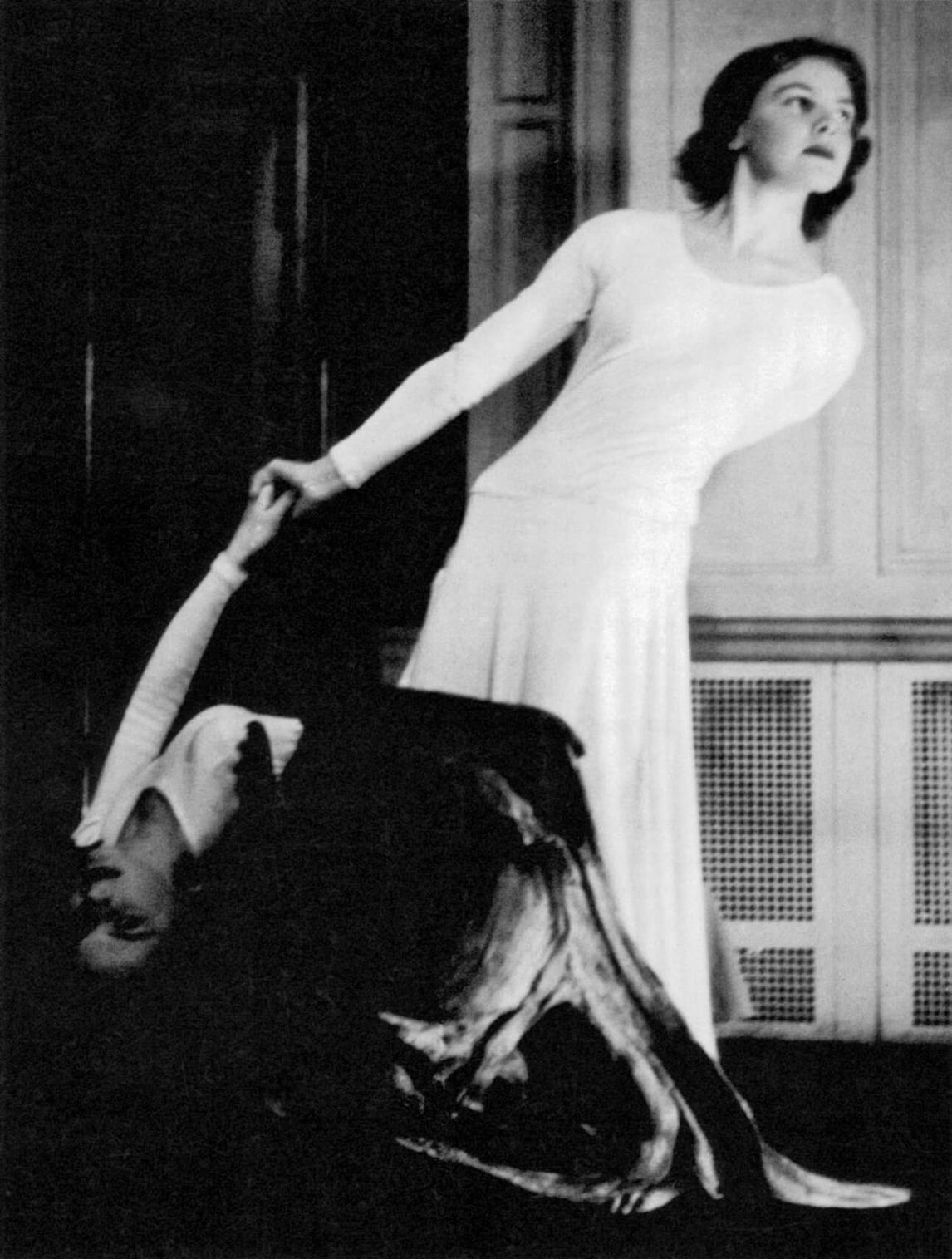

On April 3, 1948, Sullivan teamed up with Jeanne Renaud (b. 1928), Louise Renaud’s younger sister, who had just returned from New York, where she too had been studying dance. At Ross House, a mansion on Peel Street where military officers held their meetings, they performed a recital comprising eight works they had choreographed to a public composed of friends and local artists; it is considered to be the first modern dance performance in Quebec. Drawing from their modern dance training as well as from the ideas developed with Borduas and the group, they tried to translate Automatiste principles into movement. They did this by favouring expression and creativity, and freeing their bodies from classical conventions. Motivated by their enthusiasm for projects by artists from the group, Maurice Perron proposed to do the lighting, while Jean-Paul Riopelle served as stage manager and Jean-Paul Mousseau created set designs and some costumes. The attending public raved about the innovative quality of Sullivan and Renaud’s work. The dance performance did not, however, attract the critical attention they had hoped for, but it drew an informed and very enthusiastic public.

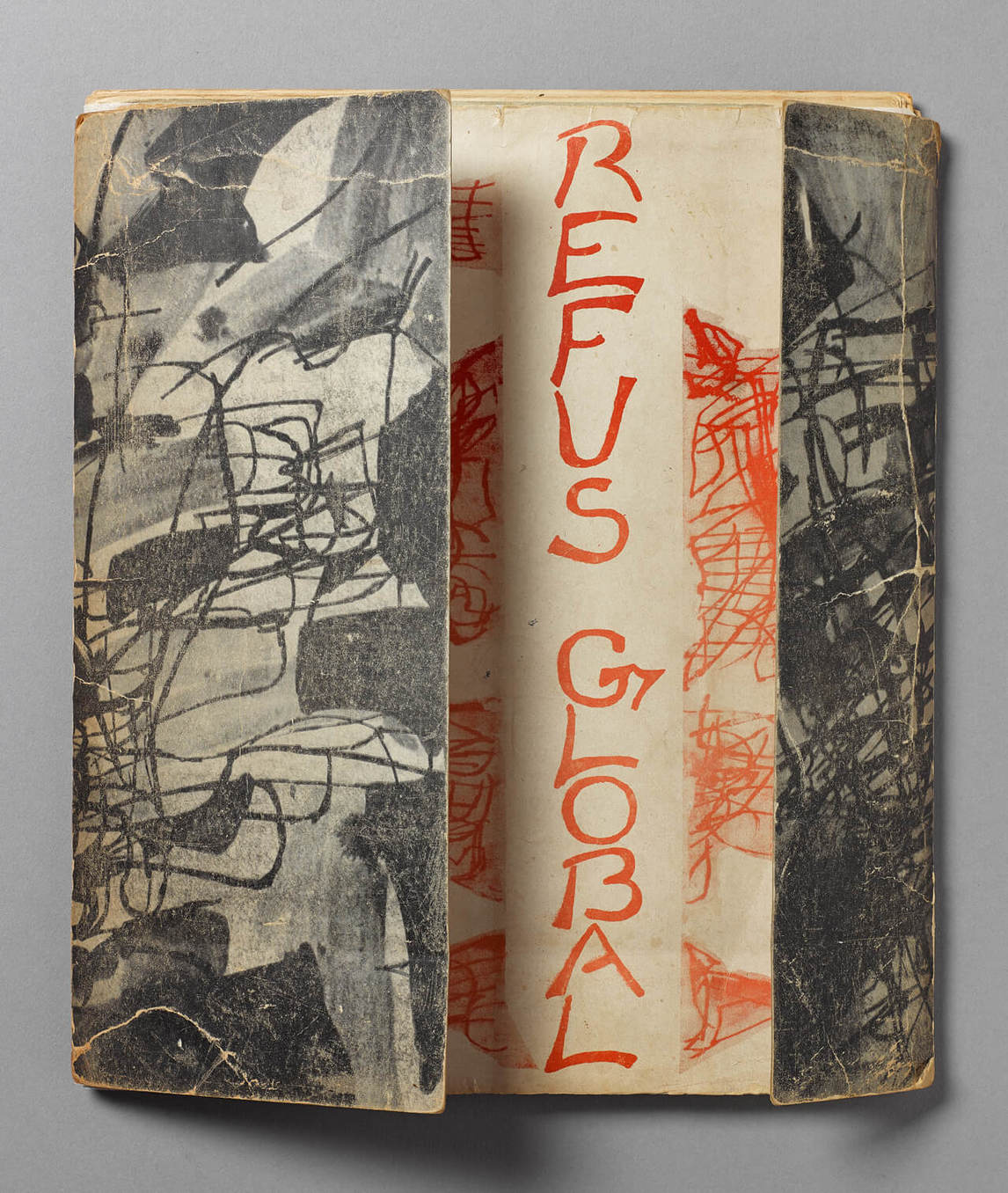

A few months later, Sullivan became one of the sixteen signatories of Refus global (Total Refusal), the famous manifesto penned by Borduas that contributed significantly to Quebec crossing the threshold of modernity. The declaration tackled much more than art; it denounced conservative and religious values, and called urgently for a social transformation that would occur through creativity. It insisted on the inherent relationship between art, social emancipation, and the unconscious, and openly challenged Quebec’s traditional values, fears, and prejudices.

Four hundred copies of the manifesto were made, and it was launched on August 9, 1948, at the Librairie Tranquille, a small bookstore that sold non-conformist and prohibited literature and was a meeting place for Montreal’s intellectuals and artists. The publication featured a cover designed by Jean-Paul Riopelle and contained, in addition to the manifesto itself, two other texts by Borduas, three plays by Claude Gauvreau, as well as contributions by Bruno Cormier (1919–1991), Fernand Leduc, and Françoise Sullivan.

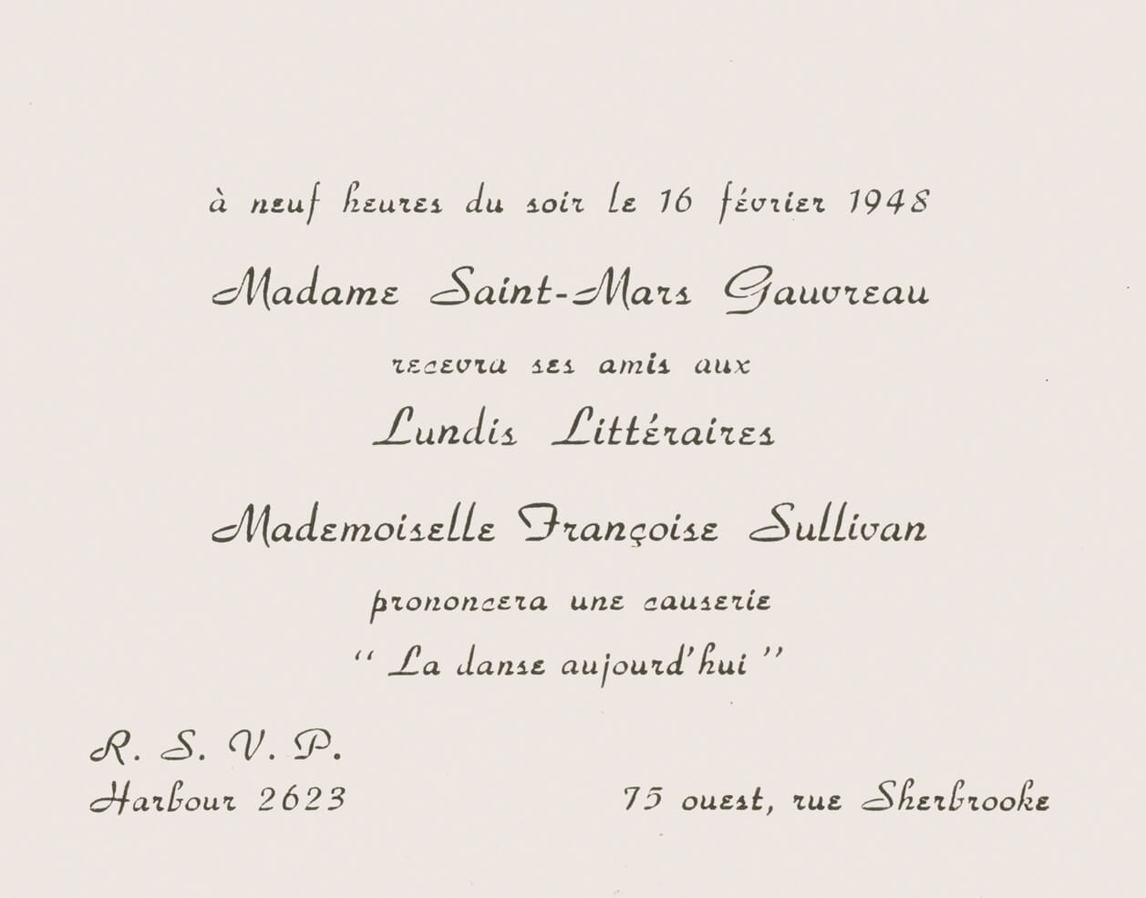

Sullivan’s piece focused on the emancipatory potential of dance. “La danse et l’espoir” (“Dance and Hope”) had originally been presented as a public talk on February 16, 1948, as part of a conference series titled Literary Mondays (Les lundis littéraires), organized by Julienne Saint-Mars Gauvreau, mother of Sullivan’s friends Pierre and Claude Gauvreau, in her Sherbrooke Street home. The text bears the traces of Sullivan’s exchanges with Borduas, as well as of the two years she spent in New York. It proposes an understanding of dance as “a reflex, a spontaneous expression of intense emotion” that is always in dialogue with the material world and primal forces.

It took courage and conviction for Sullivan to participate in this outright challenge to Quebec society. Her family was traditional, with close links to conservative politics. As she recalled, “At that time, my father was a commissioner at the Montreal Catholic School Commission, and he always talked about me with great pride. One day, the president of the commission arrived with Refus global and said, ‘Is that your daughter?’ That evening, when my father came home with the manifesto, there was a storm. But my family loved me enough to get over it.”

The publication of Refus global paradoxically marked the beginning of the end of the Automatiste movement. A few weeks after its launch, Borduas was fired from his position at the École du meuble, and several of the signatories left Quebec soon after to pursue their calling in France. Sullivan remained in Montreal to develop her career as a dancer.

1950s and 1960s: From Dance to Sculpture

In 1949 Françoise Sullivan wed painter Paterson Ewen (1925–2002). They had met on the February 1948 evening when Sullivan had read “La danse et l’espoir” to a group of Montreal artists and students in Julienne Saint-Mars Gauvreau’s living room, and had soon become inseparable. The year 1950 marked the birth of their first son, Vincent. Three more sons soon followed: Geoffrey in 1955, Jean-Christophe in 1957, and Francis in 1960.

At this time, motherhood and work were largely understood to be incompatible, but Sullivan kept up for a few years with the demands of her career as a sought-after dancer and successful choreographer, working on independent projects as well as for the CBC from 1952 to 1956. But she soon realized that she needed to change her path:

It was not possible [to continue dancing] because when you dance, you need to be away for classes, rehearsals, television shows.… At first, I remember, I had a lot of time to myself. I was playing housewife and I found it amusing. But, after a while, I got the impression I was losing my identity, and I became terrified. I felt the need to return to work, but it had to be work that would not take me away from home, that would allow me freedom to decide how to use my time. I did not want to go back to painting because my husband was a painter, and I felt this art belonged to him. So I started to make sculptures.

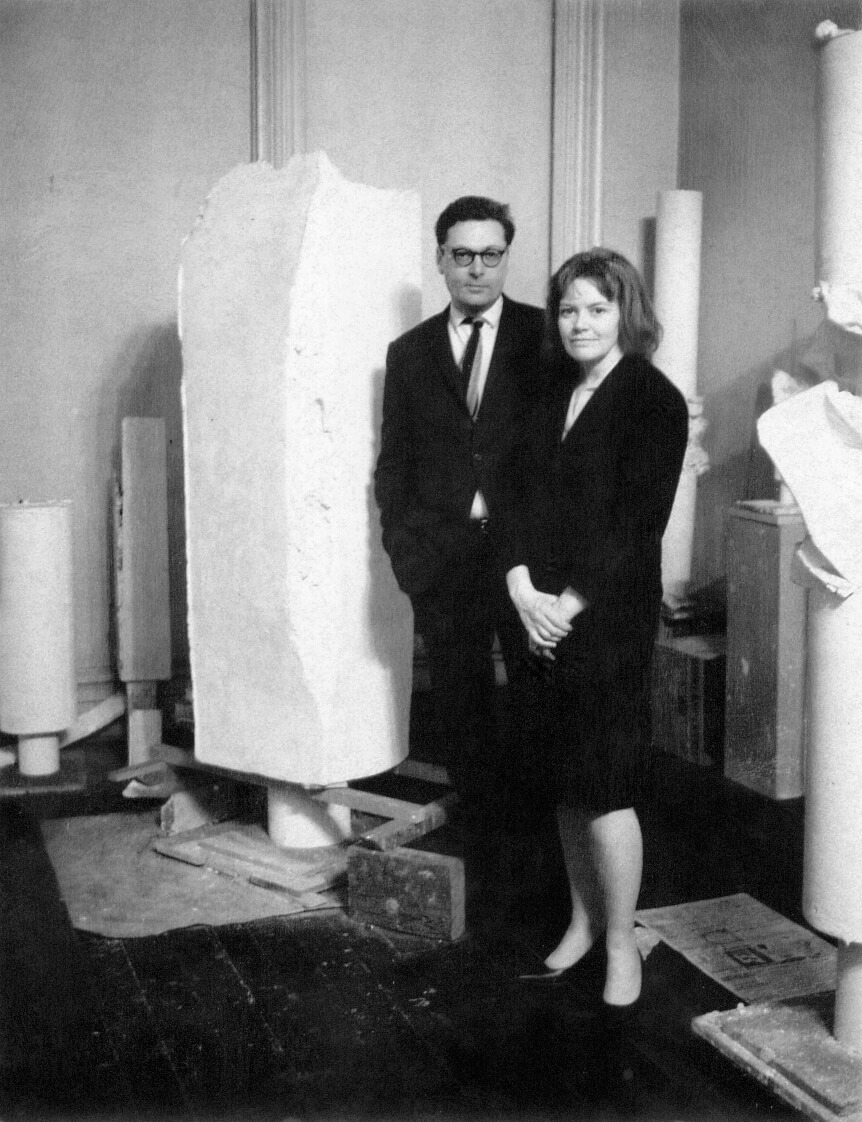

In 1959 Sullivan set up a studio in the family’s garage. Sculpture allowed her to work from home and be with her children, while also providing her with a new creative challenge. After moulding a few clay pieces, she turned to metal, assembling materials that she found in scrapyards. At this point she was self-taught. She also took professional welding lessons at the École des métiers in Lachine.

Her first sculpture exhibition took place in 1962 at the Salon du Printemps de Montréal, and the following year Sullivan received the first prize in the Concours artistique de la province de Québec, for Concentric Fall (Chute concentrique), 1962. The visually dynamic work is made of small metal shapes, a square, and several circles that are welded around a vertical axis, displaying equilibrium, energy, and graceful movement—and revealing a certain continuity with her dance work. Throughout the 1960s she also created large dynamic sculptural installations that functioned as sets for Jeanne Renaud’s and Françoise Riopelle’s (b. 1927) dance performances.

Sullivan rapidly became known as an important Canadian sculptor, showing her works in Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Paris, Milan, and Middelheim in Belgium. In 1966 she was asked to create a work that would be displayed on the grounds of Expo 67. For the occasion, she produced Callooh Callay, 1967, her largest work to date. Later that year, no longer satisfied with the mere suggestion of movement, she started introducing mobile elements into her works. She also experimented with light synthetic materials, such as Plexiglas, that offered the possibility to create fluid shapes and play with transparency.

1970s: Conceptual and Performance Art

Sullivan’s marriage to Ewen fell apart at the end of 1965, and they separated soon after. The breakup prompted her to take stock of her personal life and re-evaluate her goals as an artist. In 1970 Sullivan visited Europe for the first time, and upon her return, in spite of her success as a sculptor, she decided to embark on a new trajectory.

This was a period when artists were decrying the commodification of art and the complicity of the art world with social and economic inequalities. In order to resist the art market, many Canadian artists, such as Michael Snow (b. 1928), Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), and General Idea (active 1969–1994), developed approaches that were difficult to commercialize: performance, land art, installation. This path resonated with Sullivan, who had already explored the social potential of art through her involvement with the Automatistes and Franziska Boas. In 1973 she joined Véhicule Art, a Montreal-based artist-run centre that exhibited and promoted experimental art. It is there that, in 1976, she met sculptor David Moore (b. 1943), with whom she would often exhibit.

Sullivan’s practice from this period is infused with conceptual art ideas and techniques. She was particularly interested in experimenting with ways of making works that didn’t rely on the production of objects. In an interview given to the journal Vie des Arts in 1974, she explained: “I am returning to zero, to silence. I need to rid myself of the old art forms that no longer correspond to our reality.” Yet her art always remained embodied and sensual: she performed, for example, a series of walks during which she ambled through various parts of the city, including its industrial sites. These were carefully documented with photographs that were later exhibited. Walk between the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Fine Arts (Promenade entre le Musée d’art contemporain et le Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal), 1970, in particular, has become key in the history of conceptual art in Canada.

In 1976 Sullivan designed a guided walk for Corridart, a public exhibition organized by Melvin Charney in conjunction with the Montreal Olympic Games. Jean Drapeau, Montreal’s mayor at the time, was offended by the image of Quebec society that the works presented; many overtly exposed Montreal’s social and economic problems. To Sullivan’s chagrin, the event was shut down four days before the Games’ opening ceremony, in what was one of Canada’s most notorious episodes of artistic censorship.

Between 1976 and 1979 Sullivan began to travel more frequently. Her children were grown by then and, freed from most of the daily requirements of parenting, she again immersed herself in her work. On her own or with the assistance of Moore and other friends, she created series of photographs that documented her blocking and unblocking doors and windows of derelict houses with stones and twigs (Blocked and Unblocked Window [Fenêtre bloquée et débloquée], 1978); collecting rocks and organizing them in circles in the landscape (Accumulation, 1979); or using her body as a sundial to cast shade on ancient stonework (Shadow [Ombre], 1979). These works, which required repetitive labour and physical engagement with her environment, were inspired by Sullivan’s recurrent travels to Italy, Greece, and Ireland, where she visited rugged sites, and were created in these locations as well as in Canada. They also testify to her encounters with Arte Povera, an Italian movement that opposed artistic traditions and commodification by creating art out of non-valuable, non-traditional materials. She had met, in Rome in the summer of 1970, several members of the movement, including Yannis Kounellis (1936–2017), Emilio Prini (1943–2016), Germano Celant (b. 1940), and Mario Diacono (b. 1930), and found that their shared sensibility matched her own.

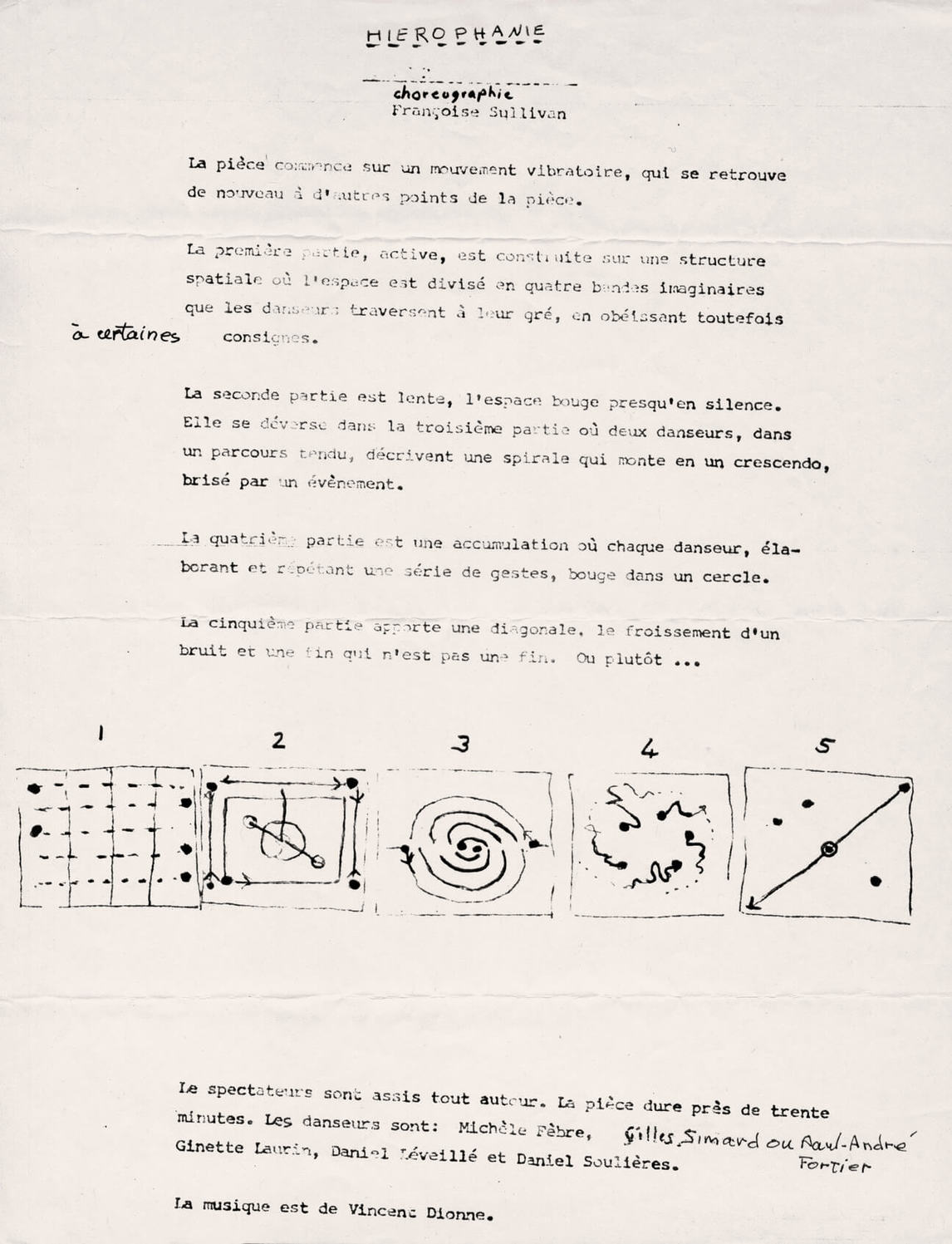

The use of her body in the production of these works, at the crossroads between ephemeral art, documentation, and performance, led Sullivan to renew her relationship with dance. After a twenty-year hiatus, she began to choreograph again in 1978, with a piece titled Hierophany (Hiérophanie). She also embarked on a new career, teaching dance, sculpture, and painting in Concordia University’s Department of Studio Arts in Montreal, from 1977 to 2010.

Return to Painting

At a time when influential art critics and artists such as Lucy Lippard (b. 1937), Donald Judd (1928–1994), Hal Foster (b. 1955), and Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945) were claiming that painting was dead, Sullivan made her way back to it. Although she found joy in conceptual art, she missed the crafting of objects and spending time in the studio. As she explained, “I yearned for the long and sometimes arduous process of making works. And I had always wanted to come back to painting.”

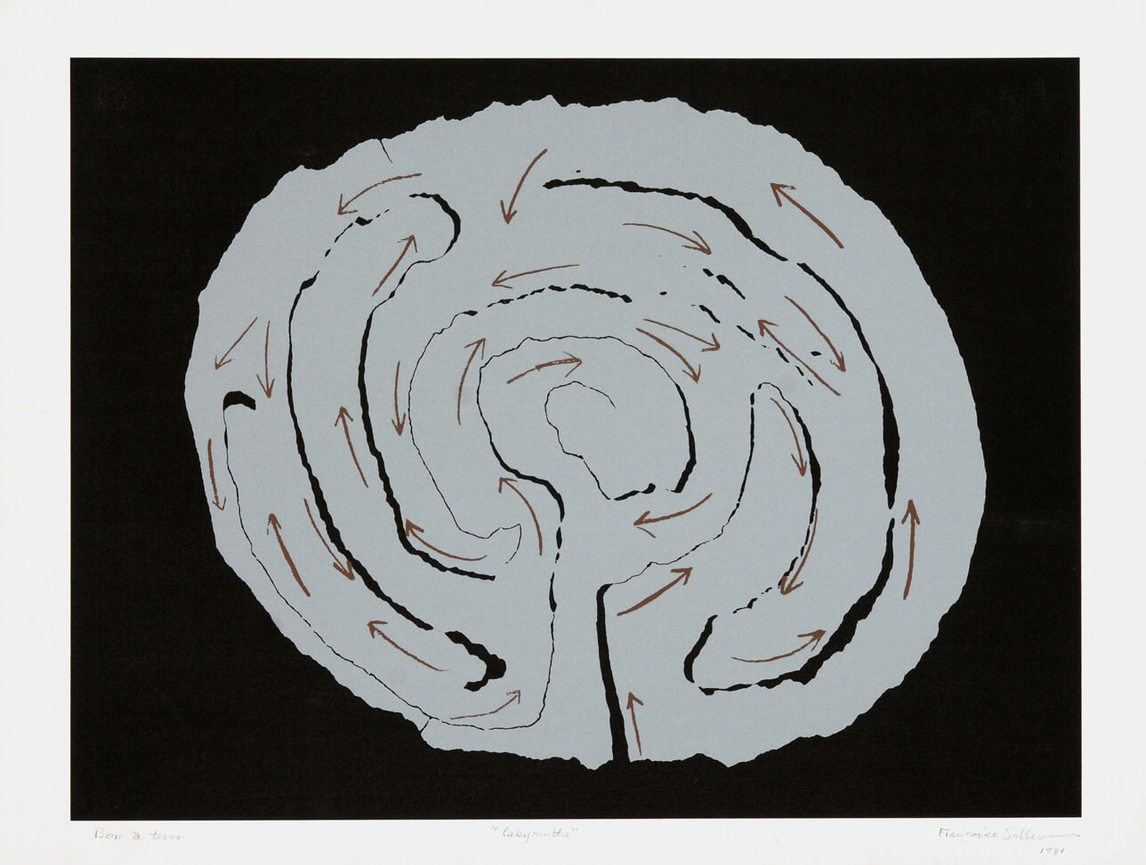

The paintings she created from the 1980s onward were clearly marked by all the experience she had garnered since her beaux-arts period as a dancer, choreographer, sculptor, and performance artist, as well as by her travels, and by her encounters with conceptual art and Arte Povera in the early 1970s. Her first exhibited series, the Tondo cycle, 1980–82, consisted of large circular canvases that had been cut up and reassembled, and to which were sometimes affixed ropes, branches, or pieces of metal. Sullivan followed this with the Cretan Cycle (Cycle crétois), 1983–85, a series that she realized on the island of Crete, where she and David Moore lived in 1983–84. These paintings are large irregular canvases populated with beast-like figures with mythological overtones, inspired by Greek history, literature, and landscape, and the archaeological sites Sullivan visited during her stay.

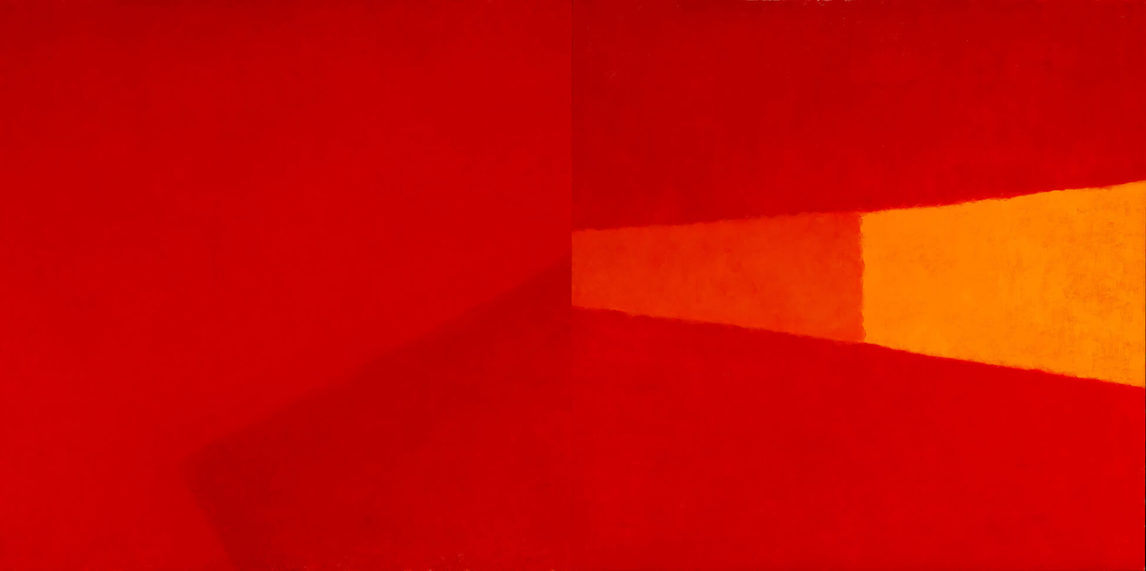

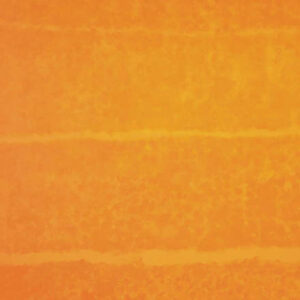

From the beginning of the 1990s, Sullivan’s painting gradually moved toward abstraction and the monochrome. Through mastery of colour and brush stroke, she developed a technique that produces the illusion of vibrations on the surfaces of her works and makes her paintings appear to glow from within. Although at first glance the large-scale canvases recall Minimalism and the work of artists such as Fernand Leduc, Agnes Martin (1912–2004), and Richard Tuttle (b. 1941), they always retain the movement and the sensuality that characterize Sullivan’s dance, performance, and sculpted works. They are also mainly improvised, or rather crafted, as though in a dialogue between the artist and her canvas. As Sullivan explains, “It’s good to have an idea to start with. But the best paintings happen when you are in a state of awareness.”

Recognition

The last few decades of Sullivan’s career have proven to be very productive and have been marked by regular exhibitions of recent works. She has also become known as one of the most enduring artists of her generation, with a professional art practice that spans more than seventy years. This recognition has generated important retrospectives of her work, including Françoise Sullivan: Rétrospective at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in 1981; Françoise Sullivan at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec in 1993; Françoise Sullivan (Rétrospective) at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal in 2003; Françoise Sullivan at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2008; Françoise Sullivan: Hommage à la peinture at the Musée d’art contemporain de Baie-Saint-Paul in 2016; Françoise Sullivan: Trajectoires resplendissantes at the Galerie de l’UQAM in Montreal in 2017; and a retrospective exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in the fall of 2018.

Sullivan has been widely acknowledged for her impact on the Canadian art world, including with the Prix Paul-Émile-Borduas in 1987, a Governor General’s Award in 2005, the Medal of the Academy of Arts and Humanities in 2006, the Gershon Iskowitz Prize for Canadian art in 2008, and the Diplôme d’honneur from the Canadian Conference of the Arts in 2009. She has been admitted into the Order of Canada (2001), the Ordre National du Québec (2002), the Royal Society of Canada (2005), and the Ordre de Montréal (2017).

Throughout her career, Sullivan has believed in constant and fearless experimentation. There is nevertheless a remarkable coherence in her work: her dance, sculpture, performance, and painting all coalesce around issues of primal energy, movement, improvisation, and art’s relationship to its environment, whether that be natural, urban, psychological, cultural, or social, always affirming life and freedom. As she herself remarked, “Everything must be connected, only the inevitable must be.”

Françoise Sullivan continues to paint in her Pointe-Saint-Charles, Montreal, studio, and she still develops performance and choreography projects.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements