Répertoire 1997

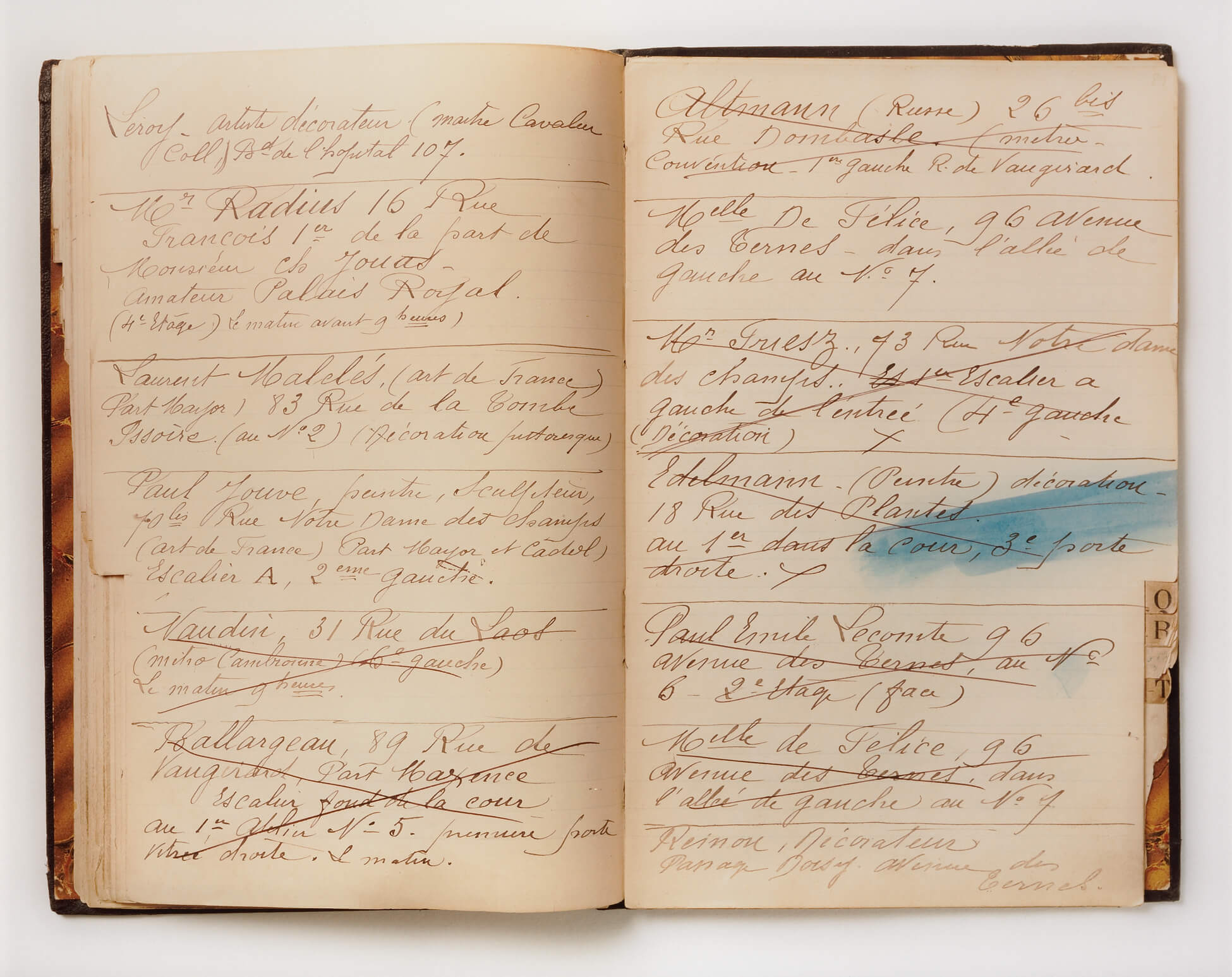

Arnaud Maggs, Répertoire (detail), 1997

48 chromogenic prints (Fujicolor), laminated to Plexiglas and framed, 250 x 720 cm overall

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Répertoire is a grid of forty-eight chromogenic prints, each one documenting a spread from an address book of nearly a hundred pages that belonged to Parisian photographer Eugène Atget (1857–1927). Arnaud Maggs’s documentation begins with the exterior front cover and ends with the exterior back cover. Each 20-by-24-inch print is framed, and when installed, the thin white frames are right up against each other, emphasizing the structure of the grid. Challenging the concept of a portrait, Maggs offers a picture of Atget—a hero of his—not through his likeness but through documentation of the photographer’s handwritten notebook. “Répertoire,” Maggs explained, “provides us with a revealing and intimate trace of the man.”

Just like Maggs, Atget got a late start as a photographer―it was his second career following some years as an actor. Though today heralded as a pioneering artist, Atget was a working photographer who saw himself as a documentarian, creating images for artists, illustrators, designers, architects, and librarians, among others—many of whom are listed in his notebook. He also documented the streets, buildings, and gardens of Paris, creating an enduring photographic record.

-

Arnaud Maggs, Répertoire, 1997

48 chromogenic prints (Fujicolor), laminated to Plexiglas and framed, 250 x 720 cm overall

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Installed at Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto, photographed by Isaac Applebaum -

Hanne Darboven, Existenz, 1989

2,261 sheets, ink and photographs on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm (each)

Collection Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation

Installed at Espace 17, 1991, photographed by Robert Keziere

Atget’s book is a business record. “It tells us what kind of clients Atget had and wanted,” Maggs wrote. “Many of the names have been crossed out with large ‘X’s, leading us to speculate on the reasons why.” Maggs would have been drawn to the X as a symbol—the ultimate cancellation. The X functions powerfully as a symbol of death. However, as art historian Martha Langford asserts, the cancellations in Atget’s book are equally about life in that they are very much connected to mundane realities of business operations. “Atget’s cancellations might have meant ‘moved,’ or ‘out of business,’ or ‘waste of time,’” she explains.

Though the project underscores mundane details, in so doing it offers a powerful rumination on time, a theme that recurs in Maggs’s work. Répertoire also shares thematic and formal considerations with the work Existenz, 1989, by Hanne Darboven (1941–2009), which was shown in Toronto in 1991 at Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation. Each photograph in Existenz represents a spread from Darboven’s diary notes from a twenty-two-year period, resulting in a massive minimalist representation of the passage of time.

Maggs draws attention to the practicalities of working as an artist and insists on their significance to understanding Atget and his practice. “Répertoire shows us another side of Atget, one we don’t usually think about—his day-to-day existence, his rejections and disappointments, his need to keep solvent,” he explained. “We see him as a human being, probably very weary.” This intimacy lends the work its power. Upon seeing it when first exhibited at Susan Hobbs Gallery in Toronto in 1997, critic Gary Michael Dault declared Répertoire “a stunningly handsome and deeply moving document.” It is a recognition of an enduring tension between art and commerce and the fine and applied arts―something with which Maggs himself was quite familiar. “I think Arnaud understood that in his early life the commercial work that he had to do prevented him from pursuing his own vision,” Maggs’s wife Spring Hurlbut (b.1952) asserts, “but at some point he gave up the former and devoted himself exclusively to his art. Of course, the skills he had acquired as a graphic designer and a commercial photographer played an important role in his work as an artist. The two things merged together.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements