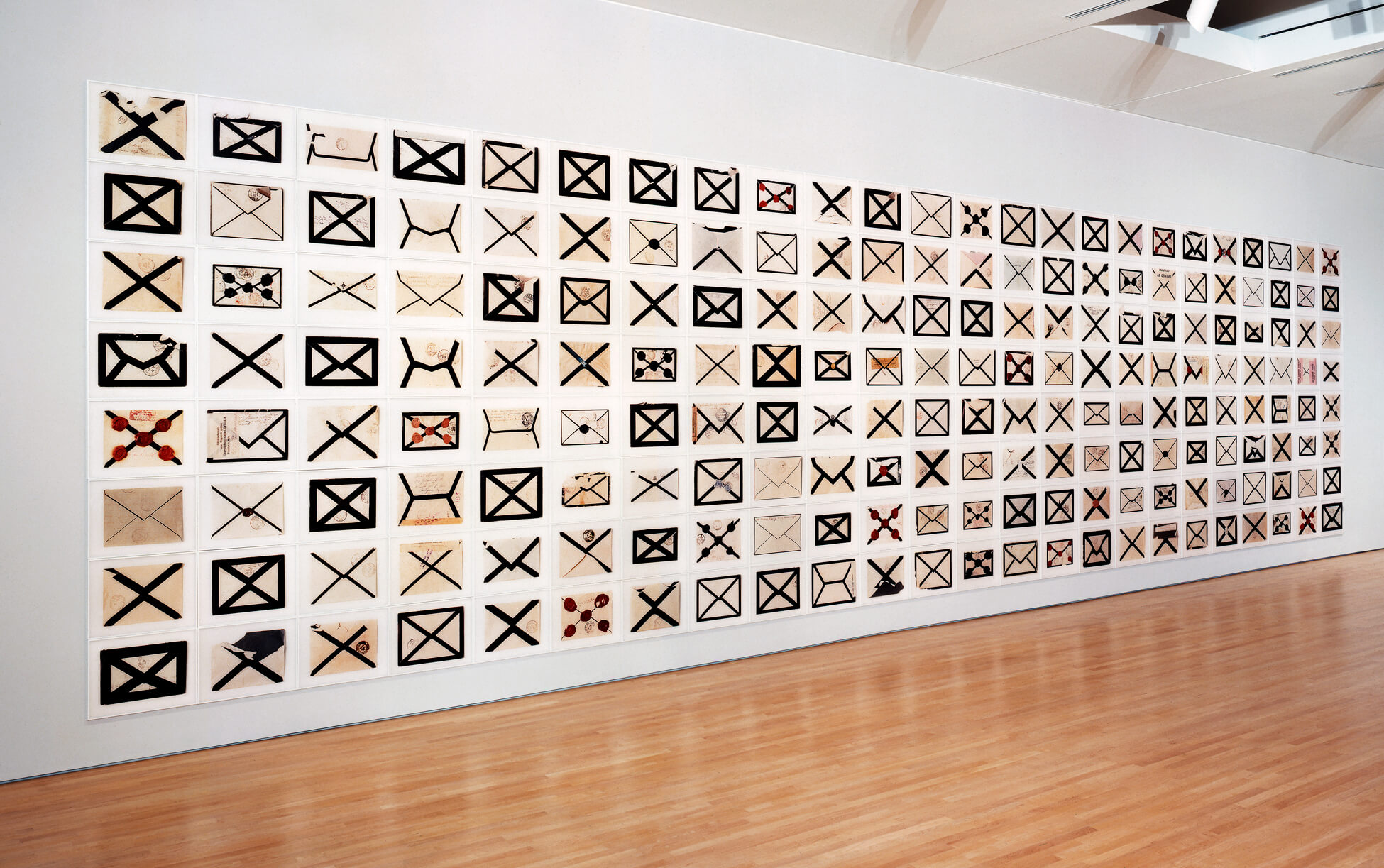

Notification xiii 1996

Arnaud Maggs, Notification xiii (detail), 1996, printed 1998

192 dye coupler prints (Fujicolor), laminated to Plexiglas, 323 x 1224 cm (installed)

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Notification xiii consists of 192 chromogenic prints, arranged in eight rows of twenty-four. It is one of three versions of a work that Arnaud Maggs made using late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century mourning stationery envelopes that he found at Parisian flea markets, shops, and through dealers. Part of a public demonstration of grief, these black-edged envelopes signalled that the sender was in mourning. Notification xiii is a particularly poignant example of Maggs’s use of found objects and photography to create a visual archive, and it is representative of his large-scale colour work that documents the graphic design of and marks of age on found paper ephemera.

Structured in a grid formation, the work uses repetition to encourage an analytical reading of the mourning envelopes. The resulting patterning and the enormity of the installation contribute to a striking graphic presence, which is amplified by the limited and high-contrast palette of black, white, and red. Maggs’s analytical eye—his interest in slight variations in form—compelled him to collect the envelopes. “I had always admired their design,” he told art critic Robert Enright, “and then one day in a shop I found 10 of them . . . I noticed that they were all different in little ways, and it immediately dawned on me that I had a piece.”

Maggs sought out as many mourning envelopes as he could find. Bold and dramatic, they offer an obvious connection to his interest in form. On the back sides of the envelopes the black edging meets to form an X. As Maggs noted, “For me, this signals a crossing out, a sign that this person no longer exists. Graphically speaking, there is nothing stronger than an ‘X.’” The Xs—punctuated on some of the envelopes with round wax stamps, as shown here—present a visual representation of death.

Maggs only photographed the backs of the envelopes in Notification xiii, denying the viewer access to the envelopes in their entirety. We cannot see the names of the sender or the recipient. “Someone has died but we cannot know whom,” writer Russell Keziere contends. “The identity is erased.” Though the human presence is felt in the work, photography renders it anonymous.

The framed Xs in Maggs’s Notification xiii wait to be filled in by the viewer. According to art historian Sarah Bassnett, the anonymity compels viewers to “substitute their own loved ones for the absent bodies.” Notification xiii and an earlier work, Travail des enfants dans l’industrie: Les étiquettes, 1994, both present paper ephemera as stand-ins. Travail des enfants dans l’industrie: Les étiquettes is a collection of early-twentieth-century labels documenting the work of child labourers in France’s textile industry. Created at a time of increased scrutiny around contemporary labour practices in the clothing industry, Travail des enfants offers political critique. In both Travail des enfants and his Notification works, Maggs calls attention to loss and puts found historical content in front of contemporary eyes—a re-remembering.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements