Arnaud Maggs (1926–2012) had a decades-long career that brought him renown and success in the realms of both commercial and fine art. In his early years, he worked as a graphic designer and illustrator, which shaped his visual language and approach to artmaking. In the late 1960s, Maggs pursued commercial photography, working in editorial fashion and portraiture, but barely a decade later he had become devoted to fine art. The grid format characterized the presentation of both his black and white portraits and his artworks featuring found paper ephemera.

Early Life

Arnaud Cyril Benvenuti Maggs was born in Montreal on May 5, 1926, to Enid and Cyril Maggs. His first name came from his mother’s father, who had been a commanding officer in a Sikh regiment in British India, where Enid and her siblings spent the early part of their childhood. After their parents died, they were brought to Canada to live with their grandparents, who had retired to Windsor, Nova Scotia. Cyril Maggs was from Wallasey, England, but his mother was Italian and Benvenuti was her maiden name. “Her family claimed to be direct descendants of the Italian sculptor Benvenuto Cellini [1500–1571],” Maggs explained. After fighting in the First World War, Cyril immigrated to Canada, and eventually both he and Enid ended up in Montreal, where they met. They were married in 1925.

Cyril was a clerk at Sun Life Assurance for his entire career, a job that supported the family even through the Depression. The household was not without tension, however: Maggs believed that “my mother generally disliked my father,” suggesting her feelings shaped his own strained relationship with Cyril. Enid adored her son. “My mother would impress upon me that I was both different from other children and superior to them,” Maggs recounted. “As a consequence, I had a combined inferiority/superiority complex.” When Maggs was ten years old, his sister, Heather, was born. From the moment she arrived, the two were inseparable. His brother, Derek, followed five years later.

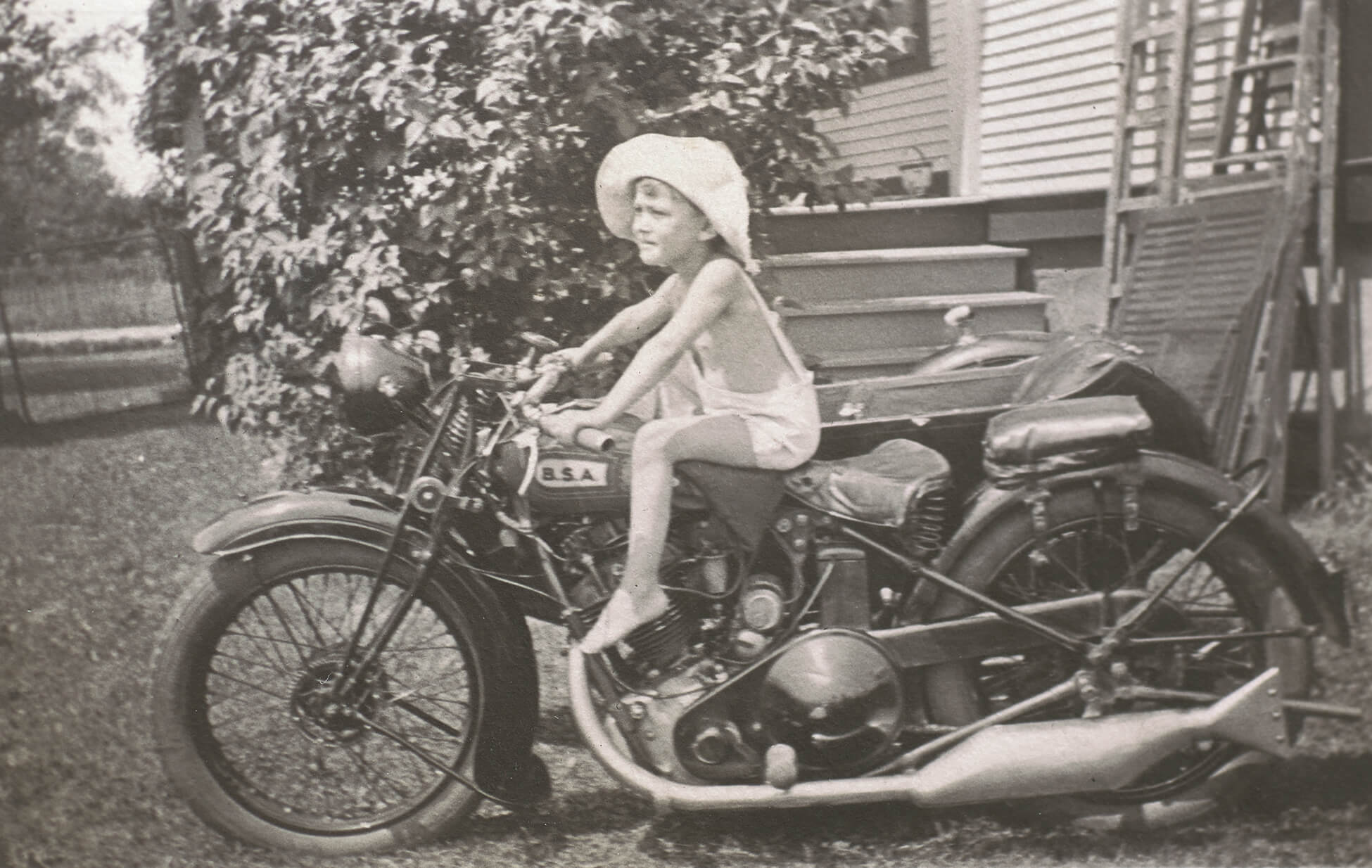

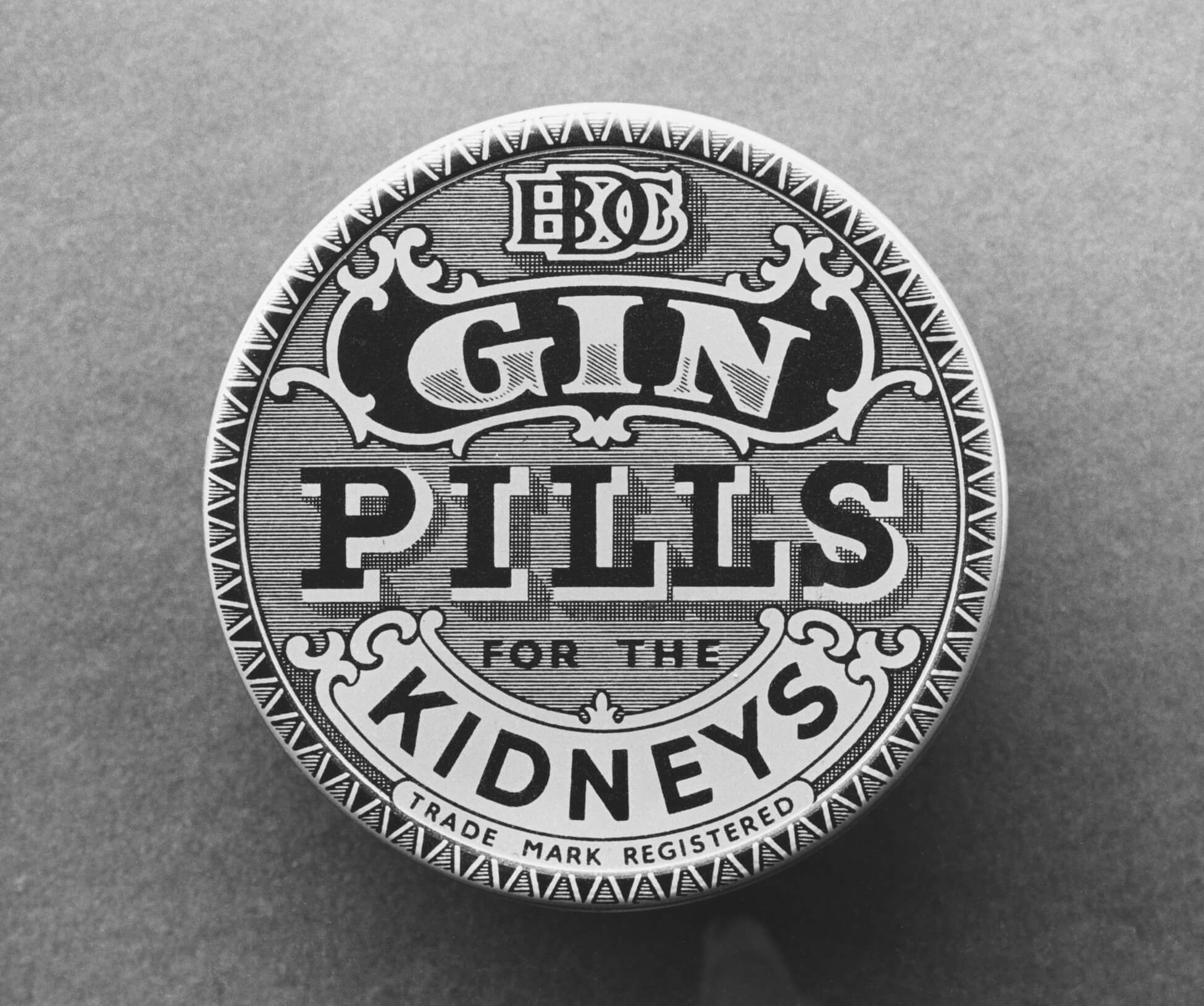

As a child, Maggs had a precocious appreciation for the formal qualities of everyday objects and an interest in collecting. At age four, he would eagerly await visits from the Popcorn Man: “He drove a motorcycle & sidecar, all white, [painted] with the words ‘Stop me & buy one.’ The top of the sidecar was a glass box, inside [of] which was kept popcorn, in rows of neat white bags.” Maggs was drawn to the little bags as aesthetic objects, and they were one of his first collections. He later recalled, “I was so fascinated I would forget to open the popcorn and eat it. There were rows of white paper popcorn bags in my bedroom on a shelf, which my mother finally threw out.” His emphasis on the visual details of the motorcycle and sidecar reflect his early recognition of the power of design and presentation. “That popcorn seller was my first art experience,” Maggs noted. “And I still love and am fascinated by vitrines.”

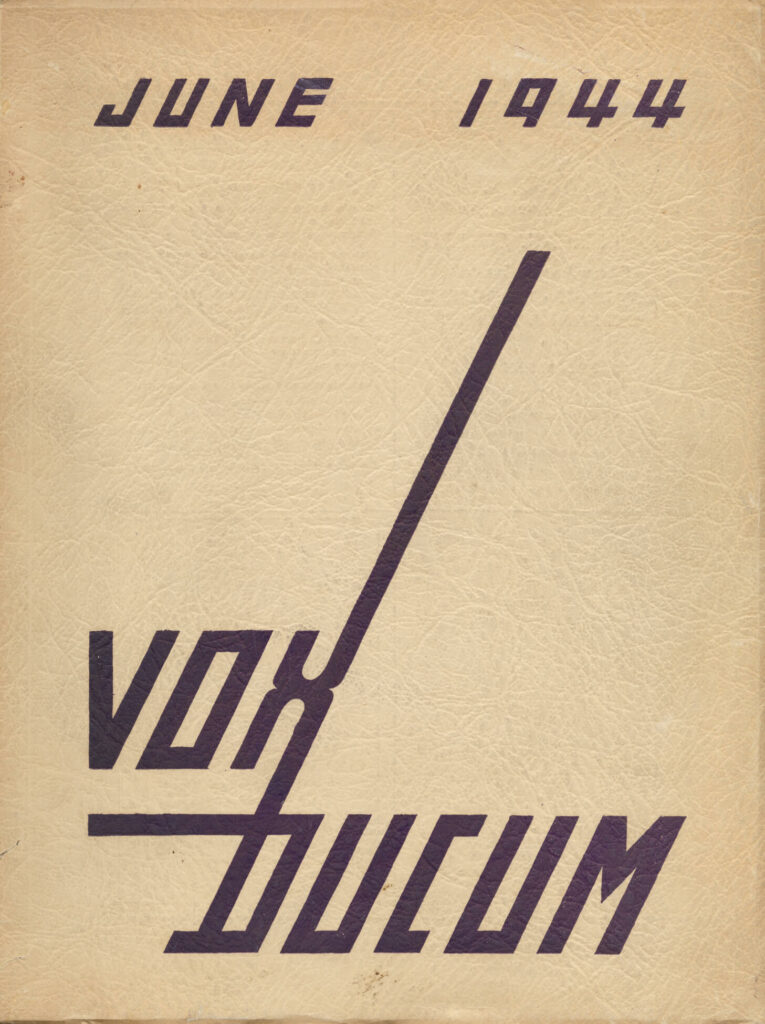

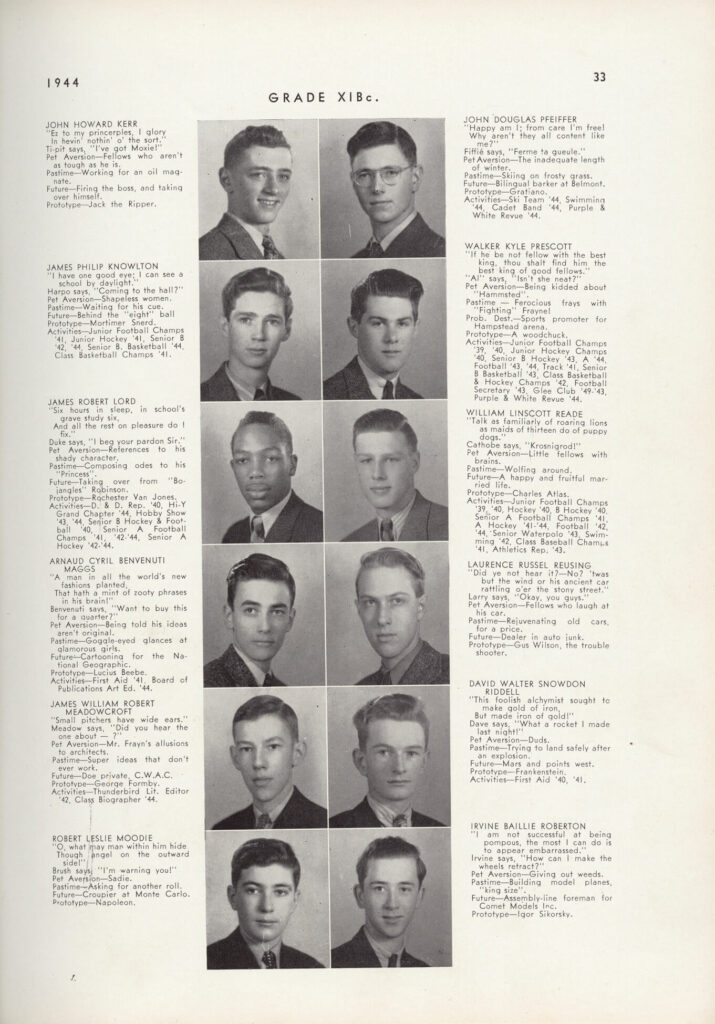

During his teenage years, Maggs showed an aptitude for design work. He made posters for high school dances, and in grade eleven, he was invited to create the yearbook cover―his first published work. In an interesting alignment with his own future multi-faceted career, in his yearbook entry Maggs cites American journalist, historian, food critic, and photographer Lucius Beebe (1902–1966) as his prototype. Beebe, himself an untrained photographer, is credited with inventing the railroad picture book genre with his 1938 publication High Iron: A Book of Trains.

Maggs also had a passion for music, forming a jazz club with friends. Spring Hurlbut (b.1952) recalls him telling stories of their antics, including how his mother shut down the jazz club because Maggs and his friends had started throwing records out his bedroom window. He would watch musicians such as Cab Calloway, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington, among others, at Chez Maurice Danceland in Montreal, a venue often packed with crowds of teenagers in the early 1940s. He and his friends also went dancing at Victoria Hall in Westmount. The Johnny Holmes Orchestra played there every Saturday night, and young Maynard Ferguson and Oscar Peterson got their starts performing with the band.

Maggs did not enjoy school and never graduated. Instead, toward the end of the Second World War he decided to join the Royal Canadian Air Force. His basic training began in 1944 in Toronto. He wanted to become a pilot, but failed the test and was instead sent to Prince Edward Island to train as a rear gunner with the No. 10 Bombing and Gunnery School. By the time he completed his training the war was nearly over. “I never saw action,” he explained, “which was fortunate, because the rear gunners were the first to get knocked off.” With the war’s end, Maggs decided to enrol at the Valentine School of Commercial Art in 1945. Although he quit after only a month, his interest in commercial art remained.

Design and Illustration Career

In 1947 Maggs was hired to work as an apprentice at the Montreal site of Bomac Federal Ltd., a studio and engraving house that also had locations in Toronto and Ottawa. At first he did a range of tasks, such as cutting mats and changing paint, to support the other artists. Impressed by their work, his design aspirations were cemented and he committed to developing typographic skills. “I quickly realized that I wanted to be a ‘layout man’,” he explained. “To do this I needed to acquire an excellent knowledge of typeface and the ability to execute them faithfully by hand.” While apprenticing, he designed an anniversary emblem for Sun Life Assurance Company. “I was 21 at the time,” Maggs noted, “and won a contest for best design plus $25.”

Maggs eventually went to Toronto, where he continued to hone his skills as a letterer at Brigden’s Limited. He also met Margaret (Maggie) Frew, a fashion illustrator at the studio. The two married in 1950 and moved to Montreal. There Maggs went to evening lectures given by Carl Dair (1912–1967) at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Having no formal education in design, he found lectures like these important.

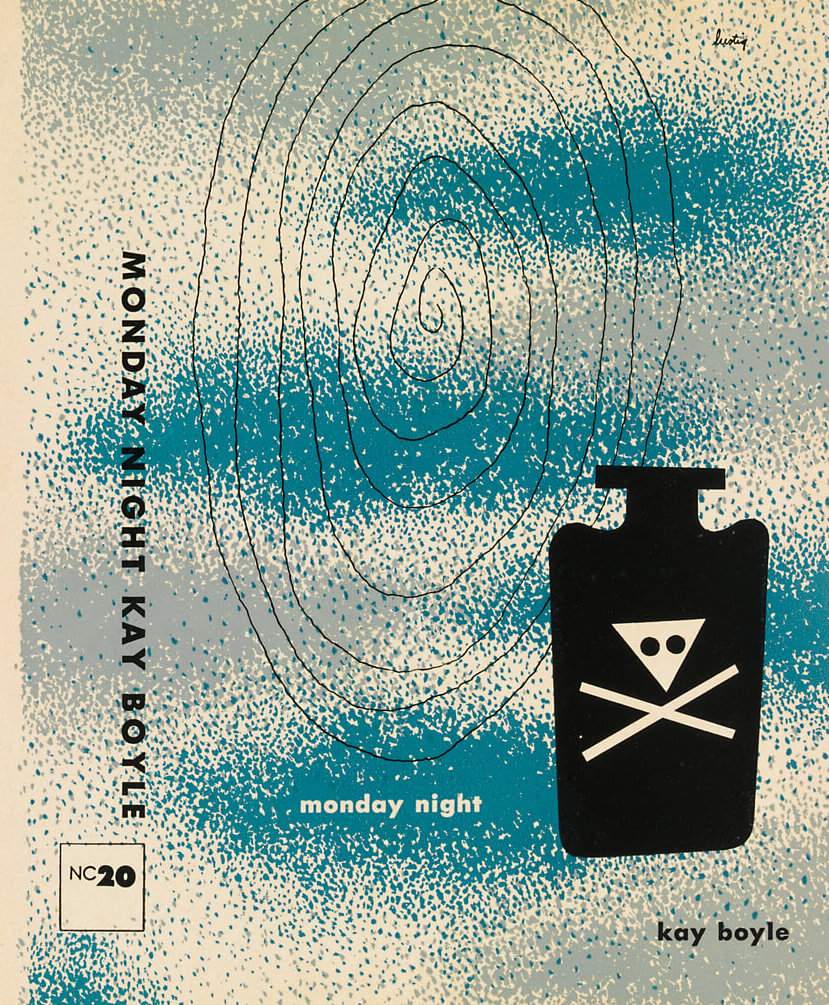

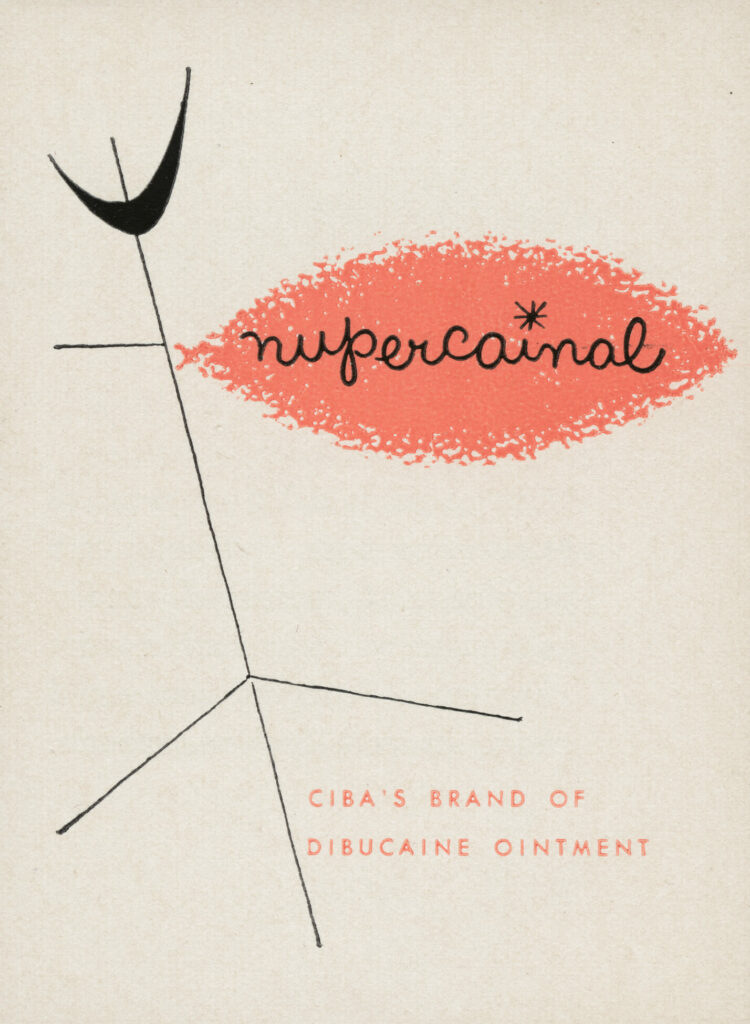

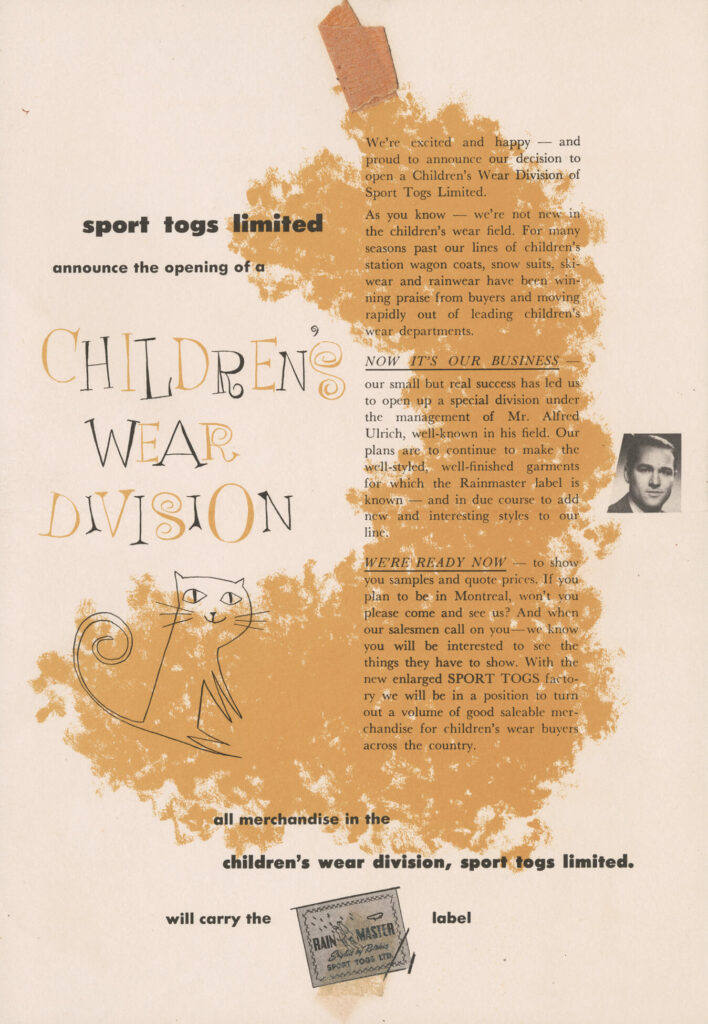

In 1951, Maggs’s first son, Laurence, also known as Lorenzo, was born. That same year, Maggs started work as a freelance designer and illustrator. He offered layout work and design and illustration services to a range of local clients, including Sport Togs and Ciba Company. As a member of the Montreal Art Directors Club, he encountered another noted graphic designer, Alvin Lustig (1915–1955), who delivered a lecture at a club meeting in 1951. “It was a thrilling experience,” Maggs wrote. “He helped my unarticulated thoughts become clear.” Lustig insisted, “If you’re going to be an artist it has to permeate every cell of your being, it has to inform all your decisions, day and night, 24/7.” In a pivotal moment, Lustig’s lecture inspired Maggs to move to New York City with his young family.

In New York, Maggs worked as an illustrator and freelance designer and took evening classes in design. His time in the city shaped his work ethic and attention to detail. “I think what influenced me the most,” Maggs explained, “was the professionalism and the drive to excel, which I hadn’t experienced in Montreal. Art directors would send me back again and again to my studio to make a drawing better.” He also met designer and illustrator Jack Wolfgang Beck (1923–1988), who influenced his work. Through Beck, Maggs connected with other New York designers, including Rudolph de Harak (1924–2002) and Jerome Kühl (1927–2016). Beck had established the Loft Gallery in his Manhattan studio, where he would show the artwork of local illustrators. Among them was Andy Warhol (1928–1987), who, like Maggs, began his career in commercial art. When Warhol’s drawings appeared on Beck’s gallery walls, Maggs purchased three of them for $5 each.

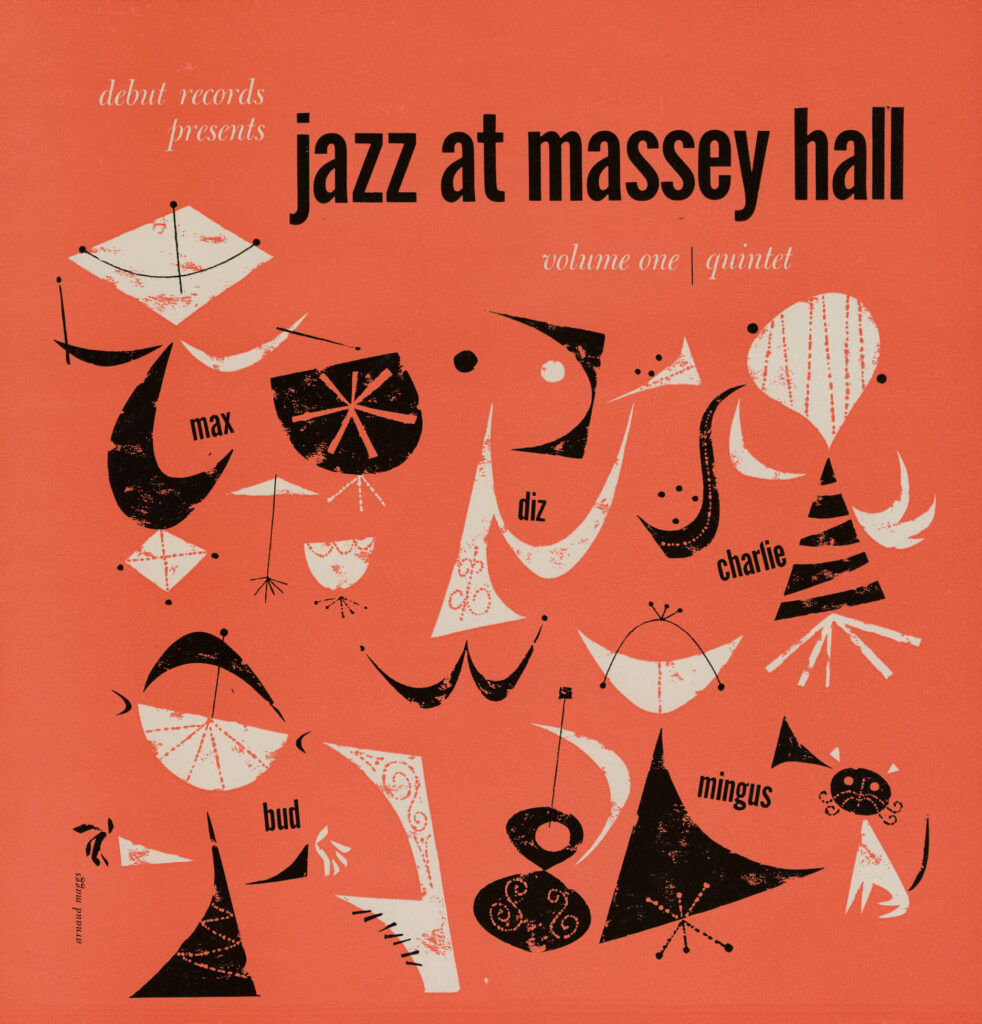

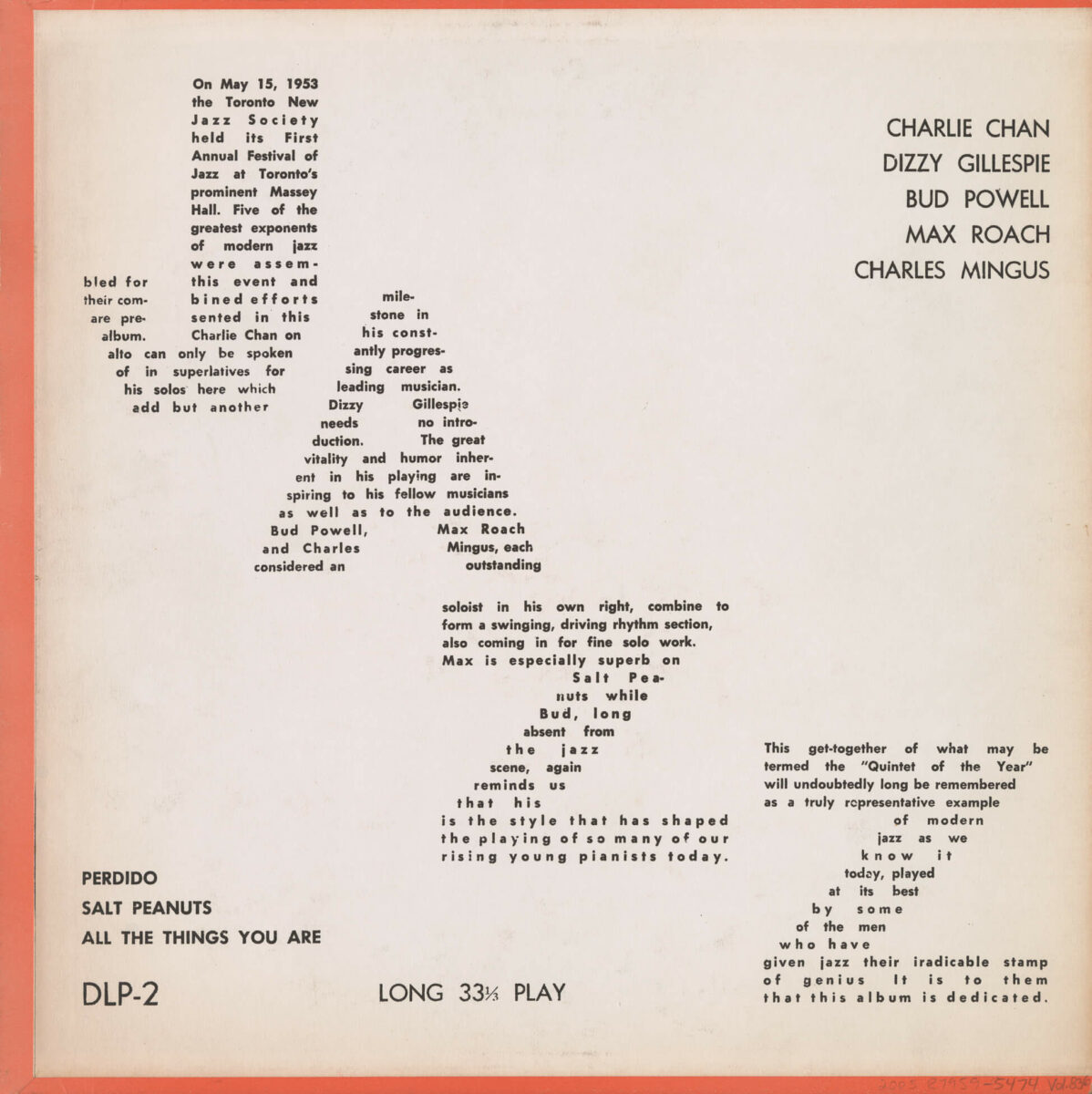

Maggs’s interests in design and jazz coalesced in New York. He produced album covers for Columbia Records and Prestige Records, including one for Jazz at Massey Hall. The now-legendary recording features “The Quintet”—Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, and Max Roach. Following a meeting with Mingus and Roach, Maggs mapped out the design on the L train back to his studio. The artwork of Jazz at Massey Hall exemplifies his playful approach. On the back of the album, Maggs explored space and typographic form by setting the copy inside large letterforms spelling “JAZZ.”

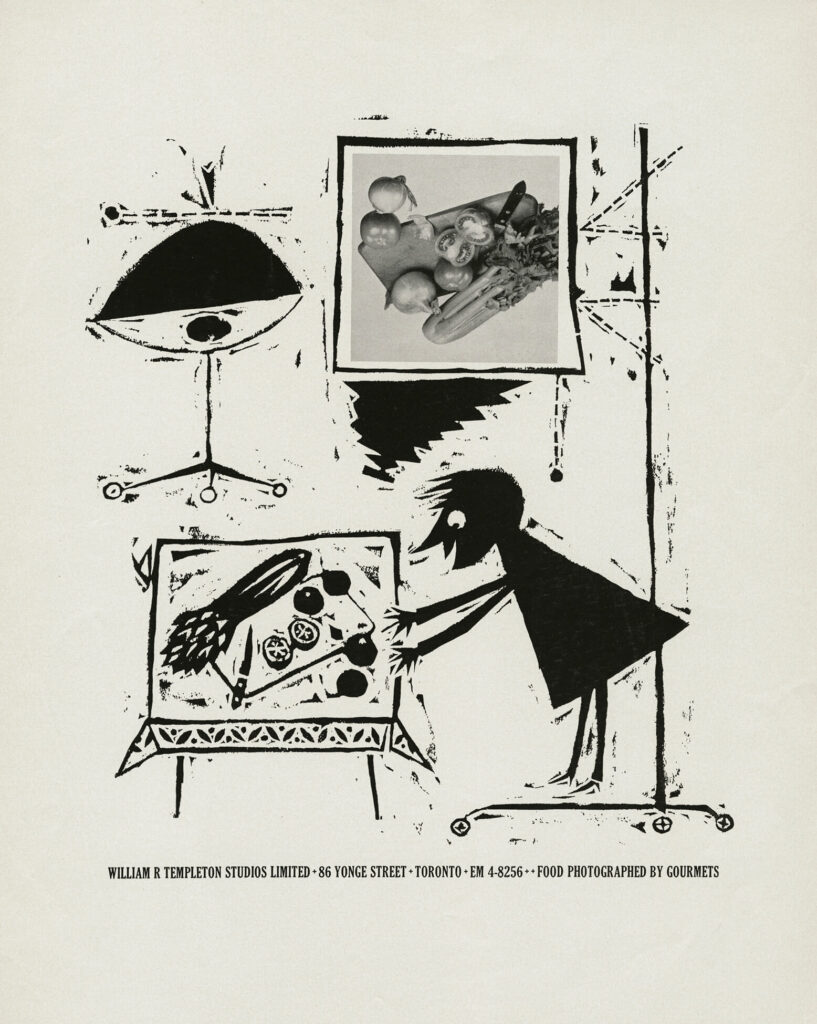

It was a challenging time, however. As Maggs later recalled, “We couldn’t afford to go to a movie, much less hear some live jazz. I pounded the pavement in the daytime looking for interesting work. At night I laid out full-page newspaper ads for out-of-town department stores.” Expecting their second son, Toby, the Maggses returned to Toronto in 1954, where Maggs took a post at Templeton Studios.

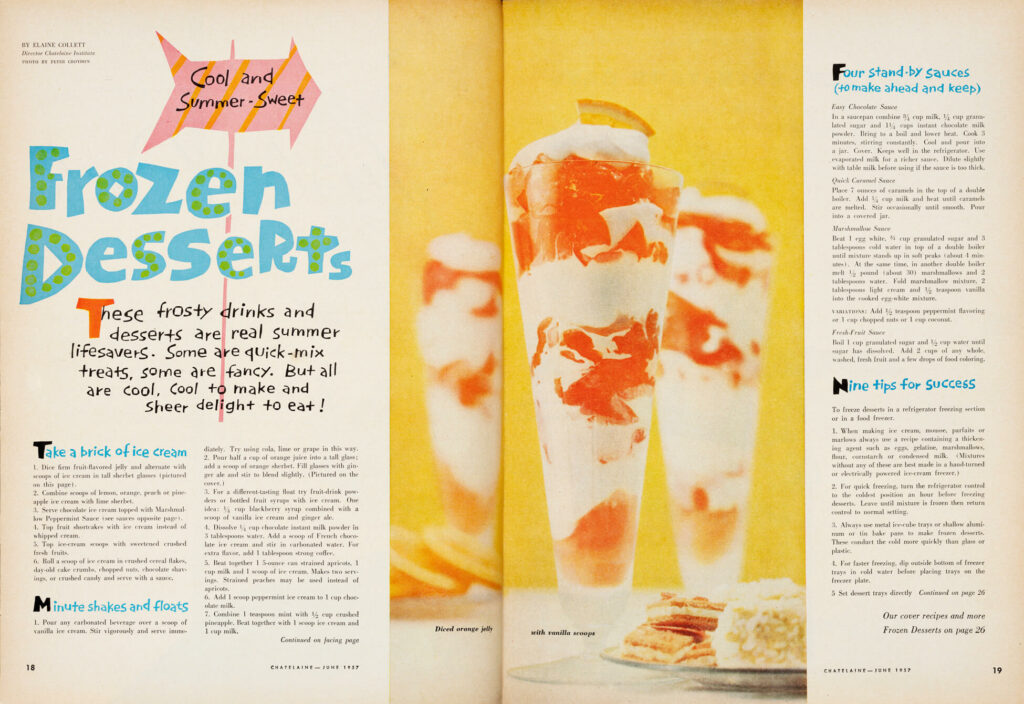

By 1957, Maggs had decided to freelance again, and he set up shop in the basement of the family’s Don Mills home. His daughter, Caitlan, was born that year. Maggs produced a range of design and illustration work, including two magazine covers in 1958 that were recognized in the 11th Art Directors Club of Toronto Annual (now the Advertising & Design Club of Canada). He also worked with photographers in his role as a designer. In 1957, for example, he collaborated with Peter Croydon (1924–2019) on an editorial project for Chatelaine. In the Art Directors Club of Toronto 1958 award listing, Maggs, who was billed as the designer, shared photographer and artist credits with Croydon.

Invited to work for leading design firm Studio Boggeri of Milan, Maggs moved to Italy with his family in 1959. Founded in 1933 by Antonio Boggeri (1900–1989), the studio had an international reputation. With a roster of design masters, including Boggeri, Aldo Calabresi (1930–2004), Max Huber (1919–1992), Bruno Monguzzi (b.1941), Bruno Munari (1907–1998), and Bob Noorda (1927–2010), the studio’s work exemplified Italian and Swiss modernism. During his tenure there, Maggs worked on designs for Pirelli and Roche Pharmaceuticals. He also took drawing classes at Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera. But his stay in Italy was brief and difficult. Maggs called the move “disastrous,” admitting that he and the family “seemed unable to cope with the change in lifestyle.” Caitlan Maggs recalls that some of the reasons the family struggled included difficulties getting paid and illness and injury befalling the children. Deciding to change course, they went back to Don Mills.

-

Arnaud Maggs, Bepanten Roche brochure for Roche Pharmaceuticals (front cover), 1959

Photomechanical print on coated wove paper, 41 x 41 cm

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa -

Arnaud Maggs, Bepanten Roche brochure for Roche Pharmaceuticals (interior), 1959

Photomechanical print on coated wove paper, 41 x 41 cm

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

-

Arnaud Maggs, Bepanten Roche brochure for Roche Pharmaceuticals (back cover), 1959

Photomechanical print on coated wove paper, 41 x 41 cm

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

-

Arnaud Maggs, Design for tire manufacturer Pirelli, 1959

Photomechanical print on coated wove paper, 31.9 x 23.3 cm

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

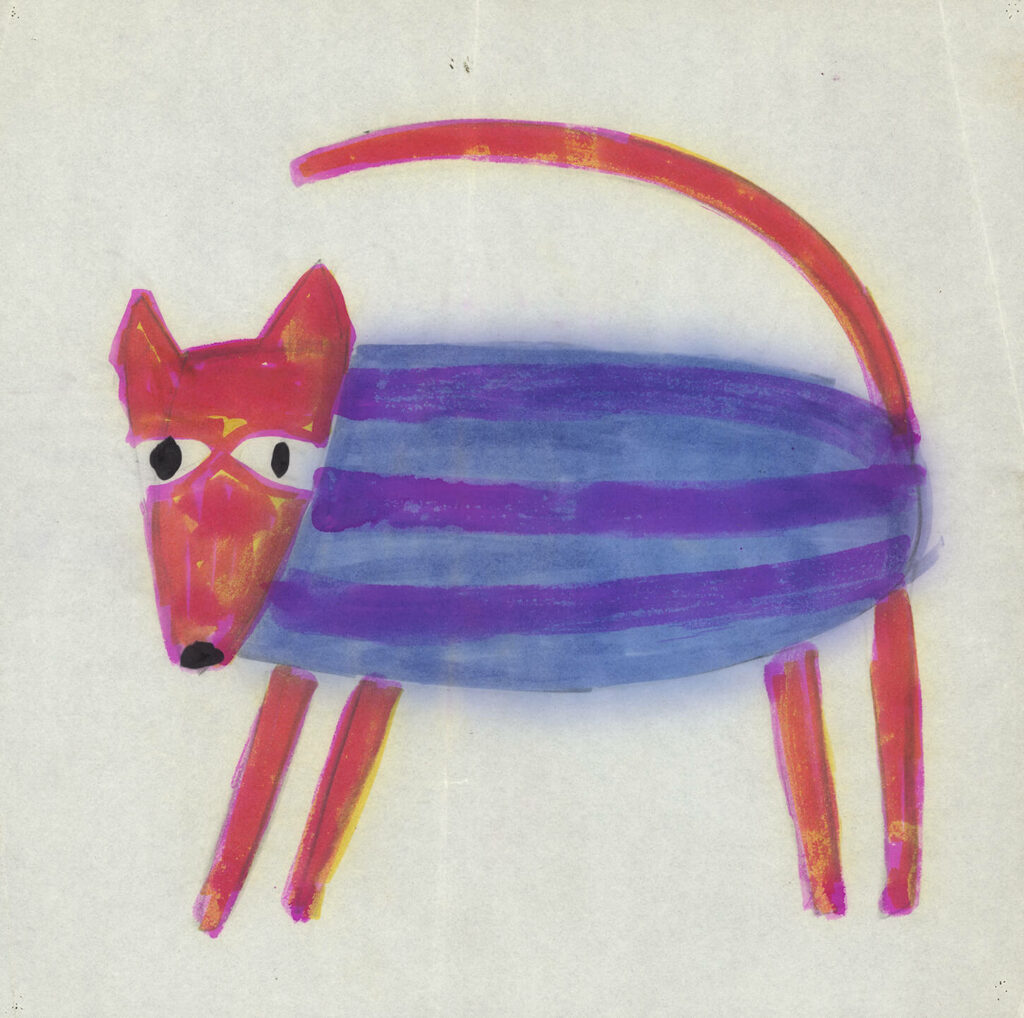

To announce his return, Maggs created a direct advertising promotional piece that depicts the artist, smiling, camera in hand. Around the same time, he became a graphic designer at Sherman Laws and Partners. Jim Donoahue (1934–2022) remembered, “My first time meeting him, he was a slick looking guy. He was tall and thin and wore really handsome suits.” His book jacket design and illustrations for Nunny Bag: Stories for Young Canada were published in 1962. These playful, childlike drawings express his ongoing fascination with the human head, and they point to a range of design and illustration influences, including Warhol and Alexander Girard (1907–1993).

In 1962, Maggs attended the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado. A long-time admirer of Girard, he stopped in Santa Fe on his way home to meet the American designer, who invited Maggs to work for him. This time, Maggs left Maggie and the three children in Canada. While in Santa Fe, he developed pillow designs for Herman Miller that, although not ultimately produced, convey the whimsy that characterizes both Maggs’s and Girard’s work.

After three months in Santa Fe, Maggs returned to Toronto where he joined notable Canadian designer and illustrator Theo Dimson (1930–2012) at Art Associates as a graphic designer. The influence of Push Pin Studios, an important firm in New York, is clear in work from this period. Later, in 1965, Maggs was appointed art director. With nearly two decades of experience in design and illustration, he frequently received accolades for his work, and was well-established as a key player in Toronto’s design scene.

Commercial Photography Career

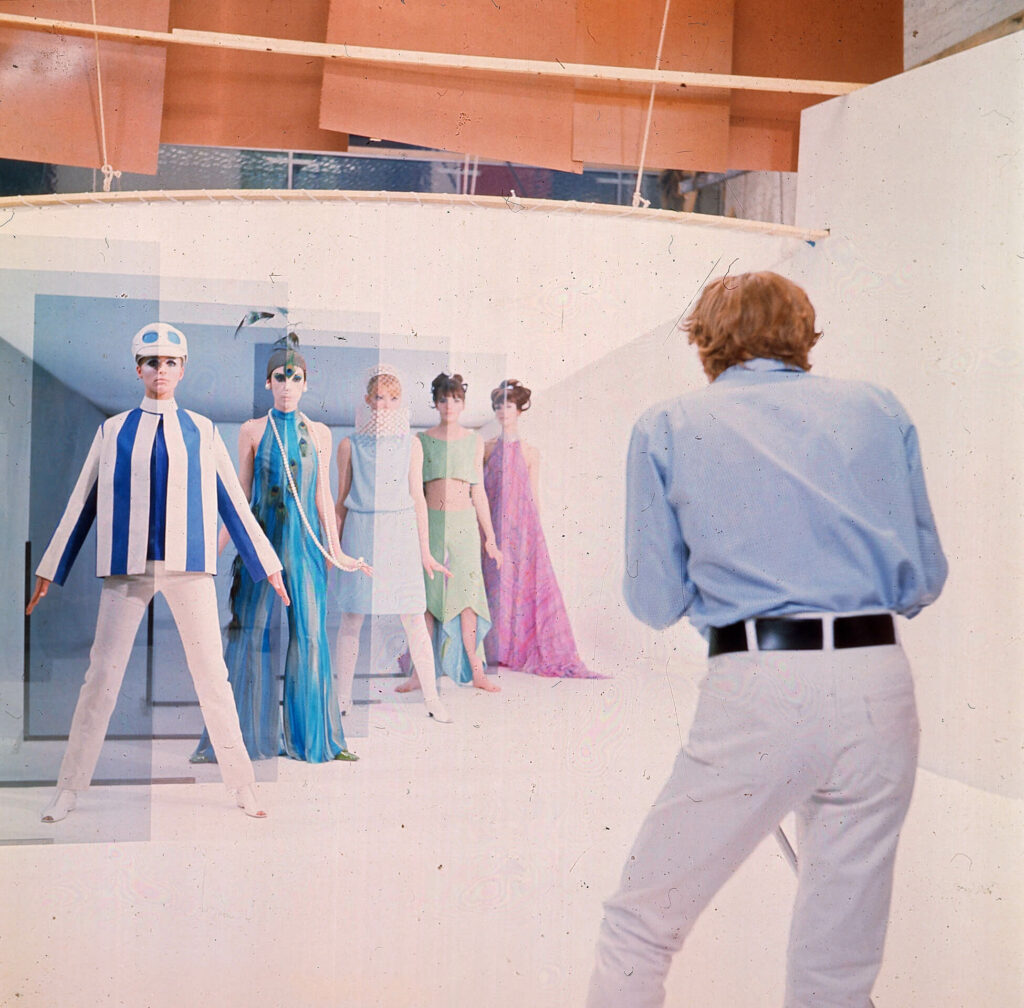

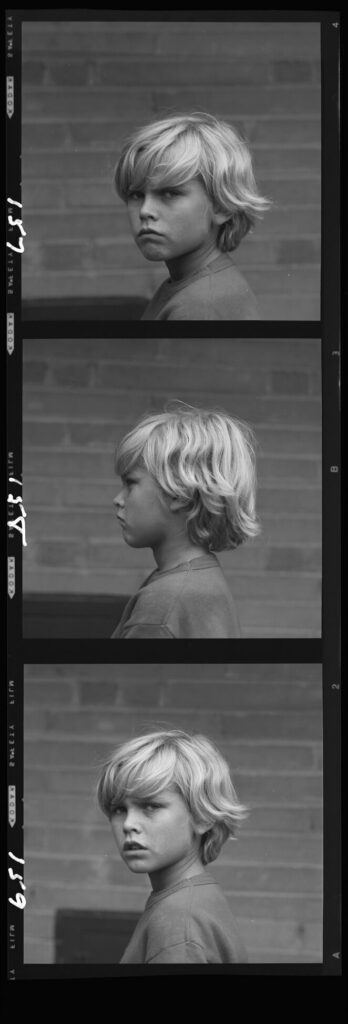

In 1966, Maggs left his job in graphic design to become a commercial photographer. It was a decision that developed out of industry exposure and a long-standing interest: since the early 1960s, Maggs had been noting film exposure times and camera settings for photographs. “He had a camera around his neck all the time,” Maggs’s daughter, Caitlan, remembers. “I had a camera and a light meter in my face my entire life!” By summer 1966 Maggs had a Hasselblad, a professional medium format camera. He took portraits during a visit to Elora Gorge and later used his children as his subjects. Without any formal training, he learned through experimentation and by watching others.

By the 1960s, views on photography were changing and it was being recognized as its own art form. In 1966 John Szarkowski, curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, published The Photographer’s Eye, in which he emphasized the inherent and particular qualities of the medium. His landmark 1967 exhibition New Documents, featuring the work of Diane Arbus (1923–1971), Lee Friedlander (b.1934), and Garry Winogrand (1928–1984), would draw important distinctions between self-expression and documentation in photography and underscore the significance of the photographer’s personal vision.

Around the same time, Canadian photography experienced a boom. Writer and photographer Paul Couvrette (b.1951) suggests that in 1967—the year of Canada’s centennial—“photography blossomed in Canada.” Public galleries were exhibiting photography, and artist-run centres were popping up across the country, offering alternatives to established exhibition frameworks. The National Film Board’s (NFB) Still Photography Division expanded its output and began a travelling exhibition program. In 1967 the National Gallery of Canada started acquiring photographs, a decision that was critical to the acceptance of photography as art in Canada.

The first English-language film of Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni (1912–2007), Blow-Up, was released in 1966. The thriller, whose protagonist is a fashion photographer played by David Hemmings, was responsible for expanding perceptions of photography in popular culture. After Blow-Up, Maggs told curator Charles Stainback, “it was quite cool to be a photographer at that moment in time.” Indeed, the marketplace was adjusting accordingly. Illustration fell out of fashion with art directors and advertisers who favoured photography in its place. As such, it could also be more lucrative. Jonathan Eby, an assistant art director at Maclean’s in 1967, maintains that “photography was attractive to a lot of designers because it was a quick and very good buck.”

Mirroring moves in the broader creative industry, change was afoot at Art Associates, where Maggs was working, and this contributed to his decision to take up photography. In 1965 Theo Dimson left the firm to start his own business. In Maggs’s autobiographical work 15, 1989, he asserts that following Dimson’s departure, “Art Associates began to cave in.” According to Maggs, it was the dissolution of the packaging department and the sell-off of their equipment that prompted his interest in the camera.

In March 1966, Keith Branscombe, then art director at Canadian Homes magazine, invited Maggs, a known collector of flea market finds, to participate in a story about decorating with objects to add personality to a home. Branscombe offered to let Maggs choose the photographer, but instead of suggesting someone, Maggs responded, “I was thinking maybe I could take the pictures.” Providing either inspiration or impetus, Branscombe’s story gave Maggs a reason to try photography in an editorial context.

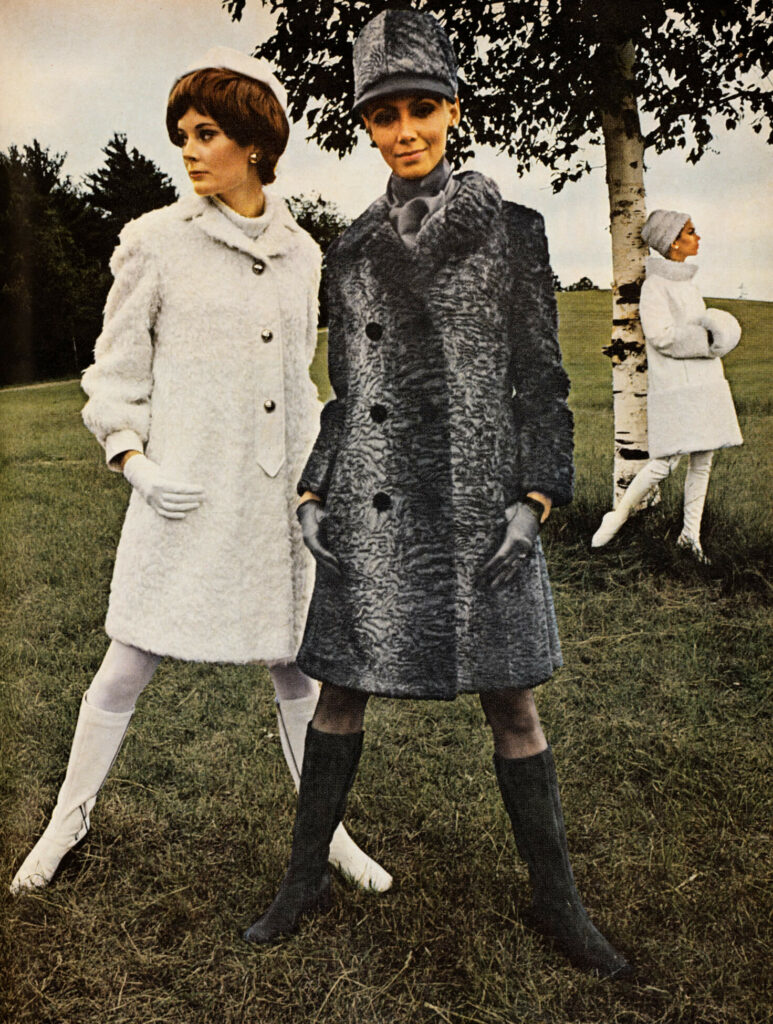

Maggs started out working primarily in editorial fashion for Canadian publications. Beginning in 1967, he regularly produced images for Maclean’s magazine, working with Modern Living editor Marjorie Harris. He was also hired by TDF Artists Limited, another respected advertising studio in Toronto, where he produced editorial fashion images and portraiture for magazines such as Chatelaine, Quest, Homemaker’s, Canadian Business, Saturday Night, and Toronto Life.

One of Maggs’s most important early photography projects was for Three Small Rooms restaurant at the Windsor Arms Hotel in Toronto. In 1968 Jim Donoahue was charged with doing “something unusual” for one of the main walls and decided on a selection of photographs to be chosen from Maggs’s existing collection. He was drawn to Maggs’s black and white images of objects, noting, “They were interesting. It would be like a really marvelous letter box that would be by the side of the road, and he’d shoot it. He shot unusual things.” Maggs’s negatives, however, reveal that he chose to photograph objects specifically for the project, and Donoahue allowed him to select the final images.

Donoahue hung the twenty-four evenly sized photographs in a grid formation, which may have been the first time Maggs’s images were presented that way. Maggs himself was unwell the day of the installation, so was not actively involved in their arrangement. Nonetheless, the project is an important precursor to the grid-based installations that would define Maggs’s later art practice.

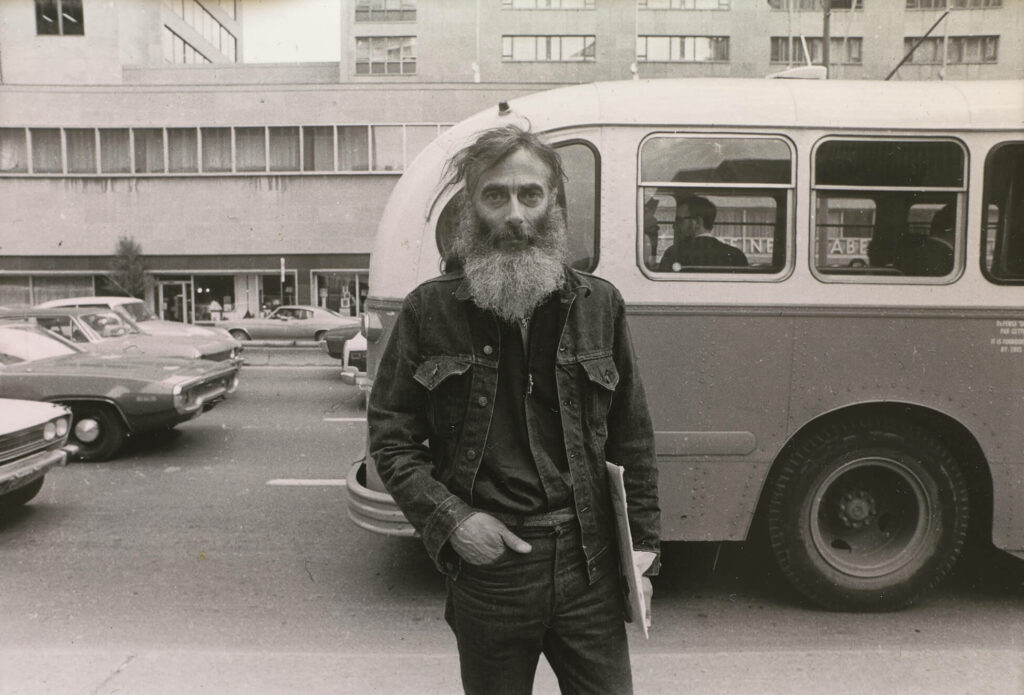

Maggs’s career switch paralleled changes at home. His marriage ended the same year he joined TDF and he moved from Don Mills to Cabbagetown, in downtown Toronto. As Caitlan remembers, “Every family we knew was splitting up. It was the new thing. It was the sixties . . . and suddenly everything shifted.” Going from ad man to wild man, Maggs’s identity also changed. Harris remembers a dramatic transformation:

He went from being really chicly dressed—fabulously up-to-date—to a guy with great, long hair and a huge beard. One time I remember the cops stopping us just because of his hair. We were on our way to do a shoot and the model was in the backseat of the car and there’s Arnaud getting stopped for driving while hairy! I mean it was unbelievable.

Though in his forties at this point, the youthful rebellion of 1960s counterculture clearly had an impact on Maggs.

Transition to Fine Art

In 1969 a Canada Council grant enabled Maggs to travel through France, Spain, and North Africa, a trip that marks the beginning of his transition to fine art. An opportunity for self-exploration, the aim was to connect with some of the photographers who had influenced him, and although that goal was not realized, Maggs felt it offered an important lesson. “For me, this was a voyage of discovery,” he explained. “I realized I had never stopped long enough to fully appreciate the world around me.”

Maggs left TDF in 1970 to work for himself, continuing to take on fashion and editorial photography assignments. In 1971, he mounted an exhibition at the Baldwin Street Gallery in Toronto entitled Baby Pictures. His artist statement for the project reads:

Arnaud Maggs has been known for many years in Toronto as an accomplished graphic artist and designer. Around three or four years ago he decided to get more directly involved in professional photography, mainly in the field of fashion. Most recently he has turned his attention partially toward a more serious treatment of his personal, non-commercial, photographic images. Thus resulted this exhibit, his first one man show of photographs.

Although he often addressed his change in career direction as an abrupt reinvention, his shift to fine art involved a period of evolution that included reflection, exploration, and overlap with his commercial practice. The text reveals an early interest in moving away from his commercial focus to explore photography as a medium for self-expression.

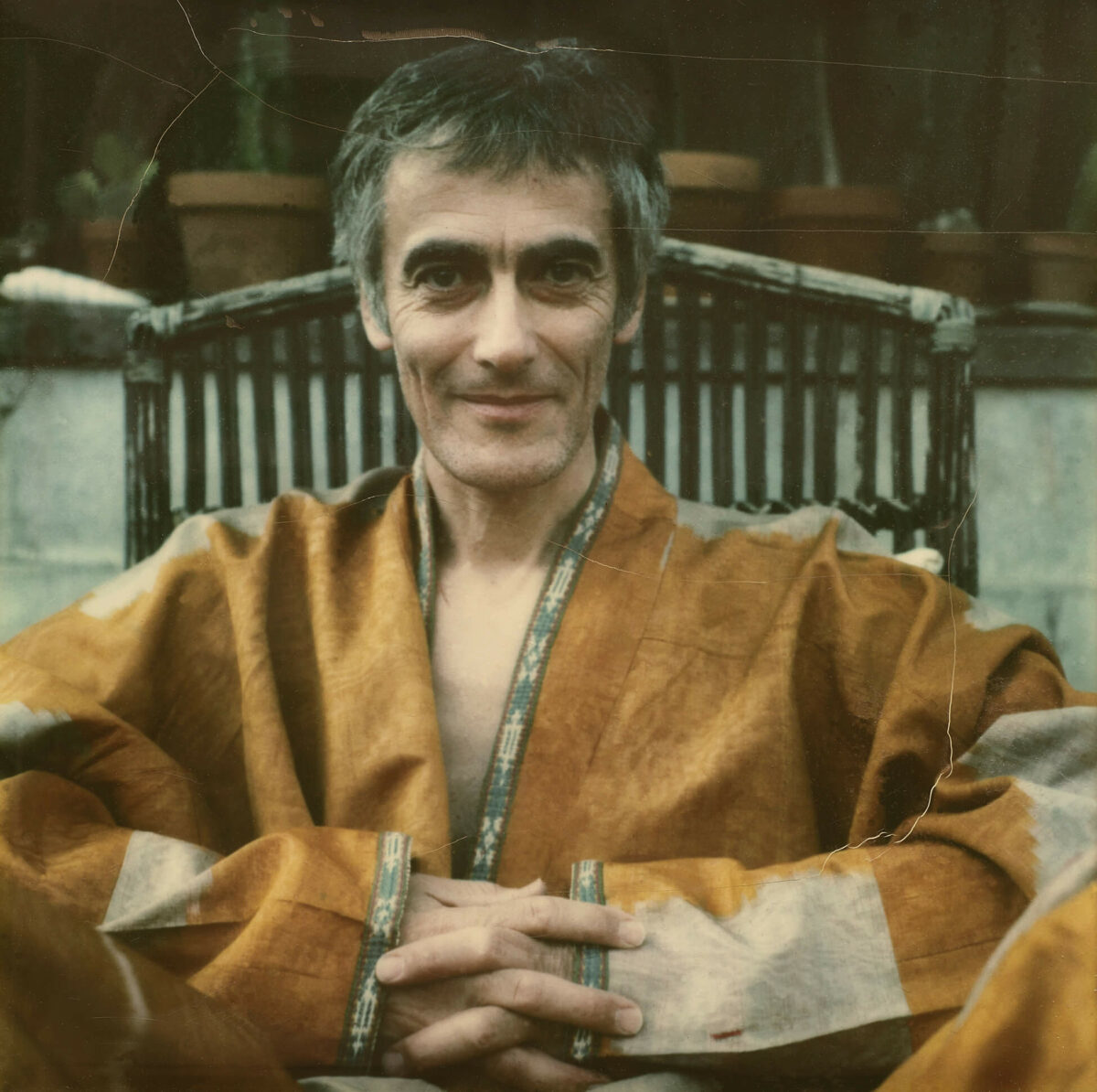

That same year, Maggs started teaching a course called Entertainment, at Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University) in Toronto. Artist Lee Dickson (b.1951) was one of his students. She remembers him showing Antoni Gaudí’s tile work in Barcelona and the Watts Towers in Los Angeles. “Everyone loved [the slides],” she explains. “We just thought it was fabulous seeing that stuff.”

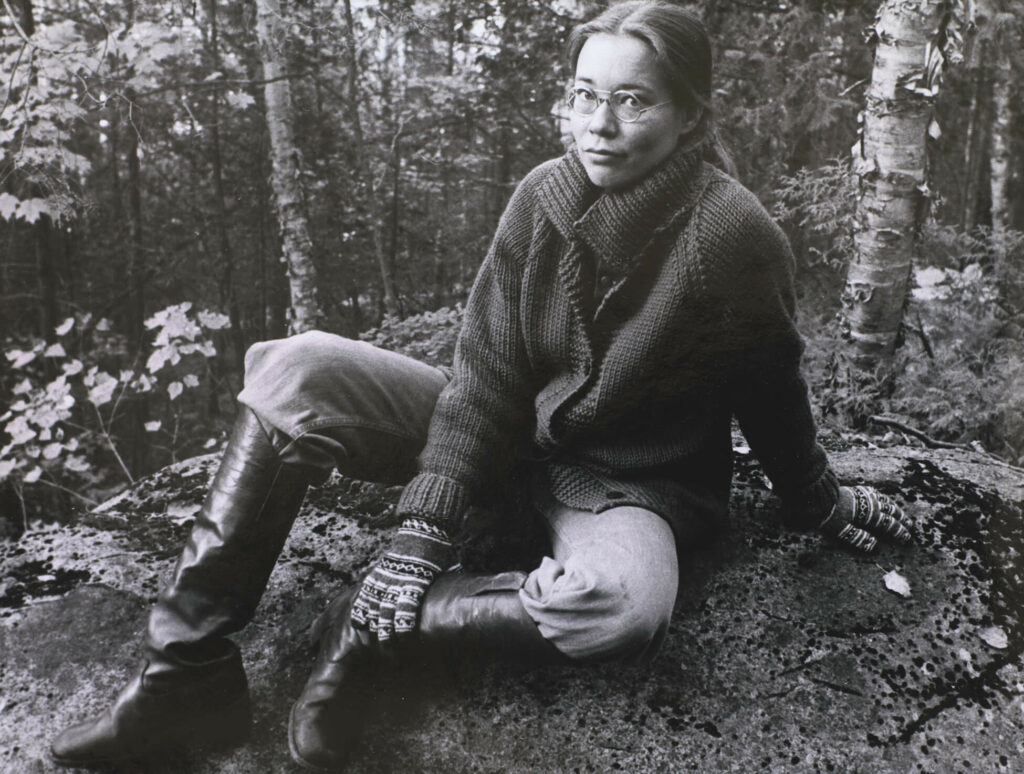

Eventually Dickson and Maggs lived together in his Cabbagetown house. “He didn’t like being a fashion photographer,” Dickson recalls. “He didn’t like trying to take pictures and having four people standing behind him.” The two would draw, write, study art, and practice tai chi. They talked about art constantly, and as Dickson notes, the decision to become an artist was a “difficult transition for him.”

By 1973, at the age of forty-seven, Maggs decided definitively that he wanted to be an artist. Commenting on his dedication and resolve, Caitlan Maggs suggests he had reached a point where he was ready to move away from client work and prioritize his own creative ideas. Significantly, this point of transition has become the persistent crux of his career narrative, where his shift to fine art is often positioned as a spontaneous reinvention. In part, this is the work of Maggs himself. He often relayed the story as a lightning-bolt moment:

Just as suddenly as I had become a photographer, I decided that I wanted to become an artist. Whatever that was. And, I sold my house, I sold my Hasselblad, and I sold most of my possessions.

The narrative was often repeated by Maggs and recounted by others in essays about his work. Aware from his days in advertising of the power of a good hook, Maggs helped to shape and define his career narrative as an artist. The reality was not quite so abrupt.

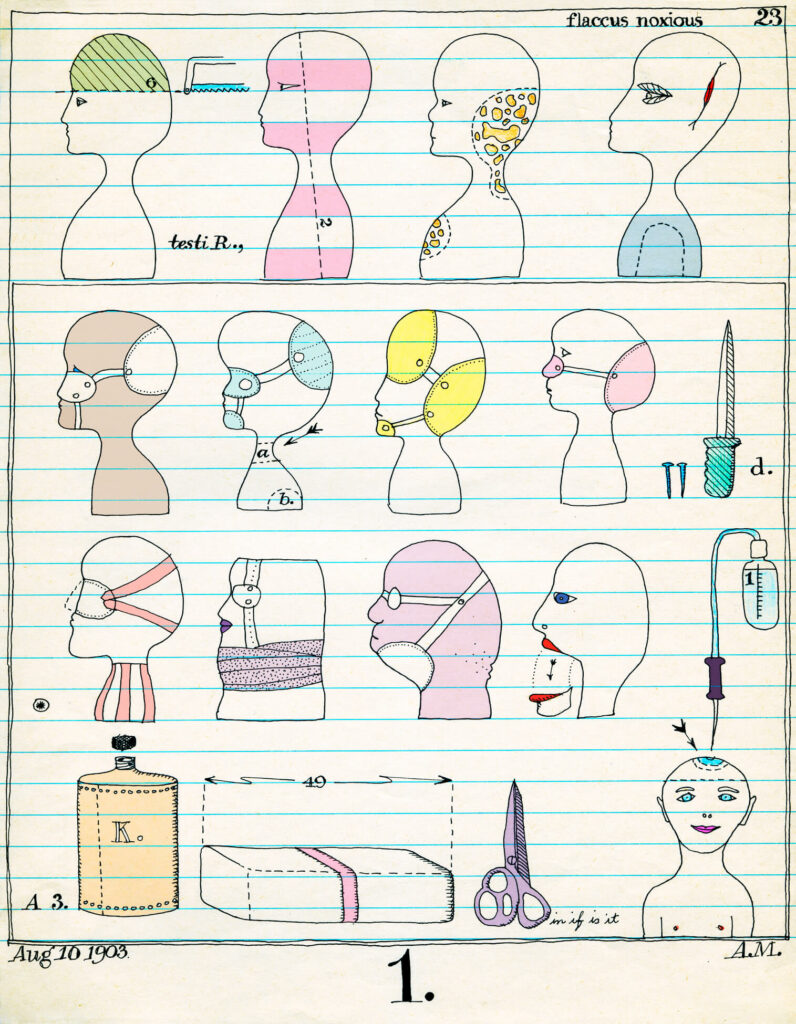

Thinking he would like to be a painter, Maggs enrolled in drawing and anatomy classes at the Artists’ Workshop. These lessons led to new ways of thinking and seeing:

One day I was drawing the model’s head, and I think it was in profile, and I thought if I drew a perfect circle the back of her head would fit the edge of the circle and her forehead would touch it and her nose would touch the circle and her chin would touch the circle. And I was suddenly just thunderstruck. I was made aware of the proportions of the human head. And, I started looking very closely at everyone from that moment on.

Though a revelatory moment for Maggs in drawing class, a preoccupation with the shape of the human head—particularly in profile—is evident throughout his career in his professional illustrations and sketches, as well as in his early photographic experiments, family photographs, and object collections.

Although Maggs felt drawing was a good place to start, he reverted to photography: “I went home and I thought well, I’ve got to show what I’m seeing, and the best way to do it is through photography because photography has an authority about it.” He bought a used camera and commenced a period of prolific photographic exploration of the human head.

Many years of overlap between his commercial and fine art photography careers emphasize the practical considerations involved in moving his focus to art. The financial struggle of working as an artist in Canada—a grant-dependent existence for many—required that Maggs maintain commercial editorial projects to subsidize his personal artistic work. “I’ve got to make a living in some manner,” Maggs explained in an interview in Photo Communique in 1982. “I’ve always needed an economic base, and it seems a good way to make a living to do photographs for magazines.” He would continue taking on select editorial work for decades.

In the early 1970s, Maggs purchased the coach house behind his large Victorian home at 384 Sumach Street with the intention of creating a separate studio space. He slowly pared down his belongings, deciding to make the coach house a live-and-work space and sell his house. Scaling back offered Maggs a sense of calm, and the sale of his house afforded some financial flexibility. In 1977, Maggs bought a building in the Aveyron region, a rugged area in southwest France where his sister had a home. Eventually, he spent his Septembers there. France—particularly its flea markets—would shape many of his creative ideas and provide the subjects for several of his later artworks based on found paper ephemera.

A Career in Art

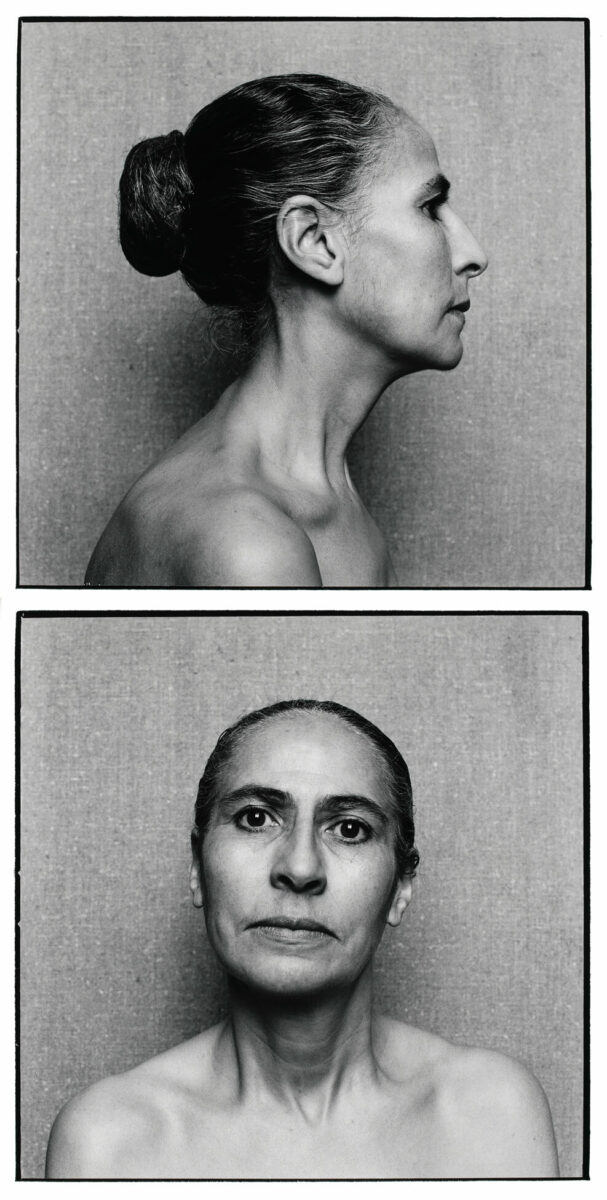

In his early years as an artist, Maggs’s work was sometimes exhibited in the context of portraiture. The exhibition Sweet Immortality, 1978, for example, showed his images alongside portraits by thirty-one others, including Tom Gibson (1930–2021), Clara Gutsche (b.1949), Gabor Szilasi (b.1928), and Sam Tata (1911–2005). At the same time, his output was aligned with Canadian artists whose creative investigations made use of conceptualist language and extended the possibilities for photography in art. Conceptual art had emerged in the late 1960s and defined a set of aesthetic strategies for artists that included repetition, seriality, procedural systems, and the use of photography.

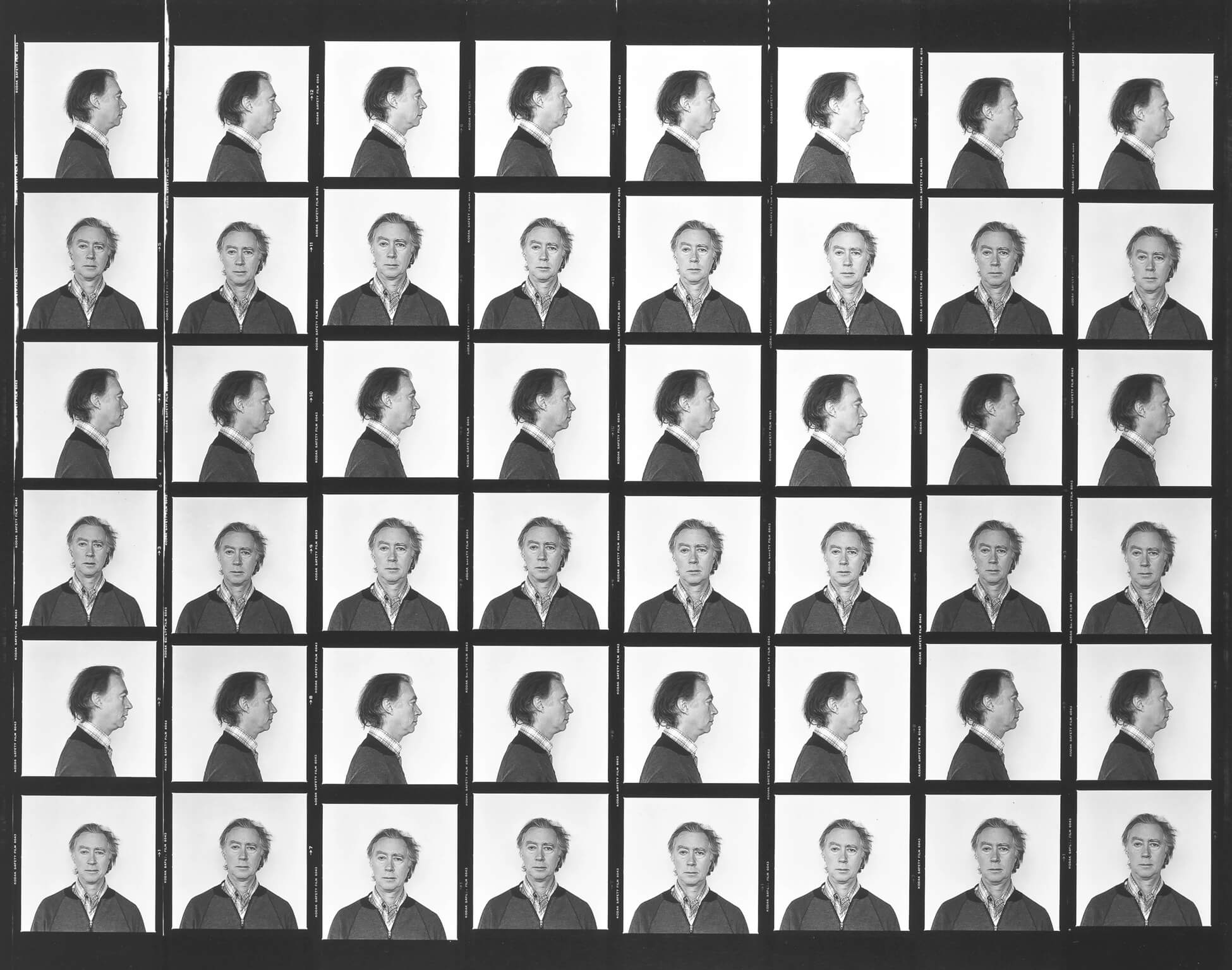

With projects such as 64 Portrait Studies, 1976–78, Maggs adopted these strategies in grid-based photographs that challenged conventional portraiture. The Winnipeg Perspective 1979—Photo/Extended Dimensions included some of Maggs’s early photographic explorations alongside conceptual projects by Sorel Cohen (b.1936), Suzy Lake (b.1947), Barbara Astman (b.1950) (who was also included in Sweet Immortality), and Ian Wallace (b.1943).

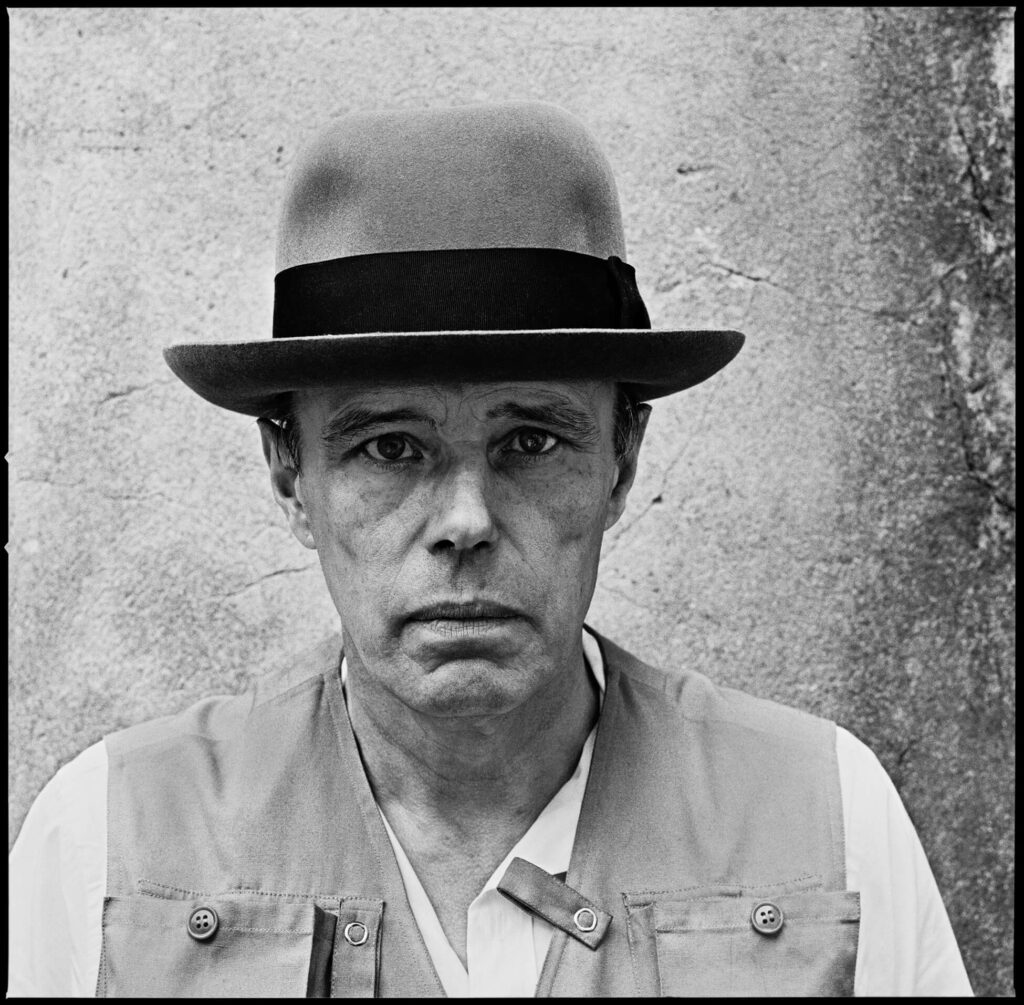

Maggs wanted to be an artist, and he consciously aligned himself with artists. In 1980, while in Europe for a solo show at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris, he sought out Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) for a portrait project. The previous year he had seen a retrospective of Beuys’s work at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. Deeply affected, Maggs felt compelled to travel to Düsseldorf to photograph him. Rather than contacting Beuys in advance, Maggs arrived unannounced at his doorstep. As Maggs explained, “I went to his house and rang the doorbell. And he answered the door himself wearing his hat.” Maggs showed him his work and explained that he would like to photograph him. But Beuys said that he was too busy. “I didn’t want to get turned down after coming all that way,” Maggs explained, “so I looked him dead in the eye and said, ‘Well, I have all the time in the world.’ It stopped him. ‘In that case,’ he said, ‘come by next Wednesday at 10:00.’” Maggs photographed the famous artist in both frontal and profile views, resulting in two massive portraits each comprising a hundred photographs: Joseph Beuys, 100 Frontal Views and Joseph Beuys, 100 Profile Views, both 1980.

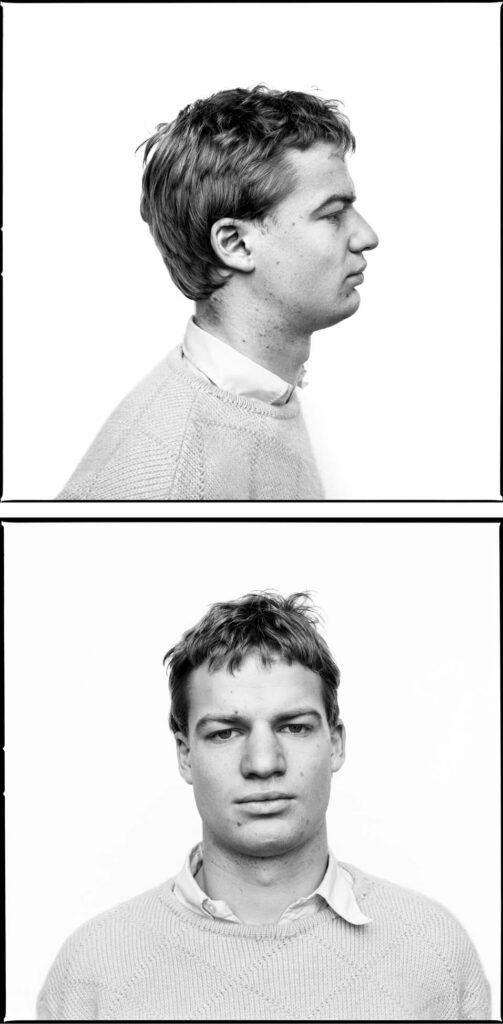

While in Düsseldorf, Maggs met and photographed Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931–2007, 1934–2015) at the Staatliche Kunstakademie in the city. He produced Kunstakademie, 1980, another serial portrait—444 exposures, or six views of seventy-four students. Now-prominent photographer of the Düsseldorf School of Photography Thomas Ruff (b.1958) was a student at the Kunstakademie when Maggs visited the school. While Maggs did not photograph Ruff for his project, his contacts were displayed in the halls and Ruff’s subsequent large-scale portraits featured some of the same students.

Back in Toronto, Maggs continued to document artists, which helped to position him within the community and strengthen his network of contacts in the art world. He photographed renowned Hungarian photographer André Kertész (1894–1985) later in 1980. The following year, Maggs worked on three grid-based portrait works using members of Toronto’s art and cultural community as his subjects: 48 Views, Turning, and Downwind. For 48 Views, 162 different subjects sat for Maggs, with each being photographed forty-eight times, resulting in a work comprising 7,776 images.

Amassed together, these portraits not only exemplify Maggs’s taxonomic interests, but also create an exhaustive visual archive—a kind of who’s who—of the Toronto arts and culture scene. Lee Dickson believes the body of work that Maggs began with 64 Portrait Studies and continued with 48 Views, Turning, and Downwind is his best precisely because of the record it affords. “It’s a great gift to the art community that he did it,” she asserts.

This period of exploration of the human head culminated in an important exhibition for Maggs at the Nickle Arts Museum (now Nickle Galleries) in Calgary in 1984: Arnaud Maggs Photographs 1975–1984. It included more than 13,000 exposures. His first touring exhibition, it travelled to Hamilton, Winnipeg, and Edmonton between 1986 and 1987. Maggs designed the show and the related publication himself, revealing the interconnections between his art and design practices, as well as the significance of space and scale to his conception of his work.

But that was a lot of faces! By the mid-1980s, Maggs sought new subjects and turned his attention back to typography. Though still directly informed by the same preoccupations with shape, scale, and classification, Maggs replaced the human head with number- and letterforms. During this time, he also explored painting, as can be seen in works such as 3269/3077, 1986, and printmaking, and experimented with different formatting strategies, including the book form. Arnaud Maggs Numberworks, which showcased a range of number explorations, was mounted at the Macdonald Stewart Art Centre in Guelph (now Art Gallery of Guelph) in 1989.

Maggs’s interest in systems of classification became more refined and overt during the 1980s and the 1990s, and he continued to use the camera as cataloguing tool. In The Complete Prestige 12″ Jazz Catalogue, 1988, for example, the images convey an existing classification system. In his Hotel series, 1991, by contrast, Maggs uses photography as a means to record cultural artifacts and invent his own typology—an archive of disappearing signs organized using letterforms as a classification scheme. Maggs’s interests in lettering, signage, and presentation and the formal and intellectual processes of design—including ordering, for example—were finding a place in conceptual art to be reconsidered. These works emphasize disciplinary overlaps in his career and the intersections between design and art more broadly. Importantly, they highlight that these connections are not just intellectual references, but rather are also rooted in his years of practice.

In 1994, Maggs was honoured with the Les Usherwood Award, a prize that recognizes exceptional contributions to the creative industry in Canada. Declaring his large-scale photographic portraits “stunning pieces of graphic design,” renowned art director Ken Rodmell pointed to both the analytical and affective qualities of Maggs’s artwork: “Seemingly clinical and detached, these marathon works of monk-like concentration and intellectual rigour told us something about ourselves that was at the same time brutal in its accuracy and yet touching.”

Taking his practice in new directions, Maggs began using found paper ephemera as his subjects, producing large-scale works that represent historical materials largely sourced in France. In 1997 Maggs married fellow artist Spring Hurlbut, who had been his partner since the late 1980s. Theirs was a creative relationship. Dividing their time between Toronto and France, the two spent their summers exploring French flea markets. Maggs and Hurlbut navigate similar thematic terrain in their work—time, life and death, and loss. In the 1990s Hurlbut commenced a number of projects that used antique cribs. Le Jardin du sommeil, 1998, for example, is a later project that features 140 antique metal cribs and cradles from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Maggs found the tags used in his work Travail des enfants dans l’industrie: Les étiquettes, 1994, when they were sourcing cribs for Hurlbut’s projects.

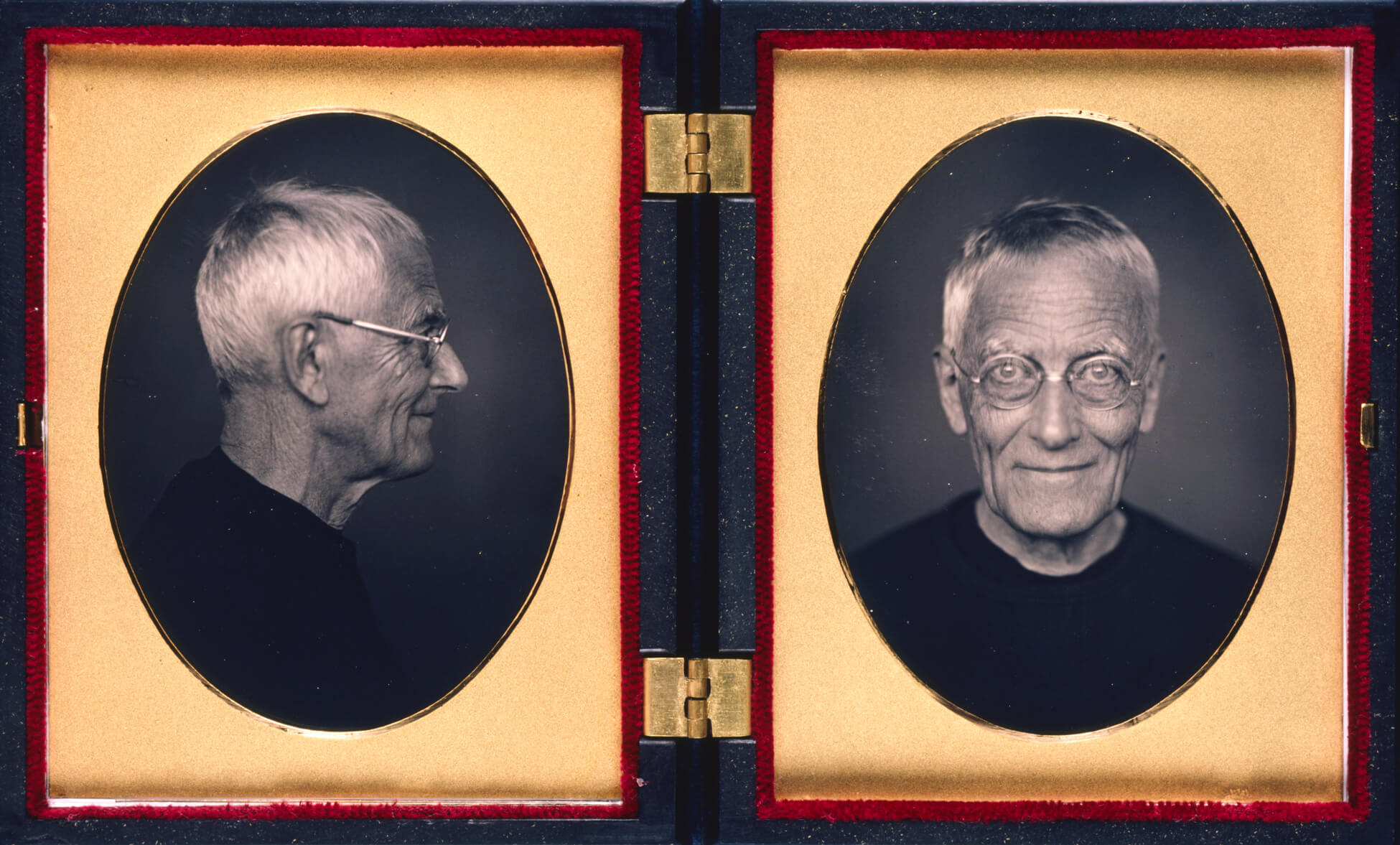

While death is a powerful thread that runs through Maggs’s artistic oeuvre, he was also mischievous. In 1998, Mike Robinson (b.1961), Maggs’s close friend and former assistant, wanted to take a tintype portrait of Maggs and photographer Gabor Szilasi, who was visiting Toronto from Montreal. He recalls Maggs arriving with Szilasi for the shoot with a rascally grin on his face: “Arnaud says, ‘We have an idea . . . We want to do it nude.’ . . . So that’s what we did.” The two men are pictured, fully nude, standing side by side.

By 1999 Maggs had been working as an artist for some twenty years. The breadth of his work was displayed in an important solo exhibition at The Power Plant that year. Beginning with 64 Portrait Studies, 1976–78, and ending with Répertoire, 1997, the exhibition showcased his dedication to systems of classification, the conceptual and structural use of the grid, and his fascination with letterforms. Maggs continued to show his work in Canada and abroad. Notes Capitales, a solo exhibition of his work, was mounted at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris in 2000. In 2006, Maggs was recognized with a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts. Four years later Maggs’s work was included in Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada 1965–1980, a travelling group exhibition that helped to define conceptual art activity in Canada.

Final Projects

Maggs died on November 17, 2012, at the age of eighty-six, at Kensington Hospice in Toronto. Before his death, his art career was recognized with a 2012 survey exhibition titled Arnaud Maggs: Identification at the National Gallery of Canada. He was also honoured that year with the second annual Scotiabank Photography Award. A related exhibition at the Ryerson Image Centre (RIC) was mounted in 2013. In 2012, Maggs completed his final artwork, After Nadar. Together, these final projects are the culmination of his interest in collections and history, and they emphasize how Maggs foregrounded the presentation of his work, particularly when using found materials.

The exhibition at the National Gallery included work from each stage of Maggs’s art career. It underscored collecting and presentation as central to his way of thinking and working as an artist. As curator Josée Drouin-Brisebois stresses, examples of Maggs’s archival source material were incorporated to “evince the shift that occurs as Maggs photographs and further transforms found objects by altering their scale and ordering them to create typologies.” To advance this aim, Drouin-Brisebois developed plans for three vitrines at the gallery, but pitched the idea to Maggs that he could organize one of them himself. “He got very excited about that,” she explains. “We shipped boxes of material from his studio… and [during installation] Arnaud just started playing like he was a little kid.” Although Maggs’s collections were featured in home decorating magazines in the 1960s, these vitrines connected his personal collection with a viewing public in physical space. The inclusion of archival material and items from his collection emphasized the significance of objects and space to his work. As Drouin-Brisebois asserts, the vitrine arrangement was “a work of art in and of itself.”

Maggs was well attuned to the role of exhibition design in shaping the experience of his artwork. In the months preceding his death, he was intimately involved in planning the design of the Scotiabank Photography Award exhibition. Participating in the exhibition layout was a final creative act.

The RIC exhibition highlighted Maggs’s return to portraiture, featuring The Dada Portraits, 2010, and the self-portraits After Nadar, Pierrot Turning, 2012. Though Maggs would appear before the camera throughout his career, these are among the rare self-portraits that Maggs deemed artworks. When Maggs first turned to fine art, he consciously aligned himself with artists. In After Nadar, he makes explicit historical references. In so doing, he similarly asserts a position for himself within the context of the history of photography.

Following Maggs’s death, Hurlbut created several artworks using his ashes as part of a larger series titled A Fine Line, 2016. At once precise and evocative, Hurlbut’s images are a fitting tribute.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements