As a defender of an aesthetic that refuted traditional artistic forms, Alfred Pellan contributed to setting Canadian painting free from restrictive ideology and delivering it into the modern era. He left his mark on Quebec at a time when the province had become suffocatingly conservative. His radical style, his exhibitions, his work with the group Prisme d’Yeux, his activities as a professor at the École des beaux-arts during the 1940s, and his efforts to resist censorship offered the possibility of creative liberation to those yearning for more than their oppressive environment would allow.

The Father of Quebecois Modernism

Pellan was a pivotal figure in introducing modernist ideas to the Quebec art scene. He encountered a relatively welcoming climate when he returned from Paris in 1940—a striking change from his experiences four years earlier, when he was refused a teaching position at Montreal’s École des beaux-arts due to his radical style. At the time of his homecoming, many of his contemporaries had never seen work with Cubist or Surrealist elements, but the prevailing attitude was one of curiosity, both among his fellow artists (such as John Lyman, who founded the Contemporary Arts Society in the late 1930s), and within the broader culture, thanks to a process of modernization that had been launched by the Provincial Secretary.

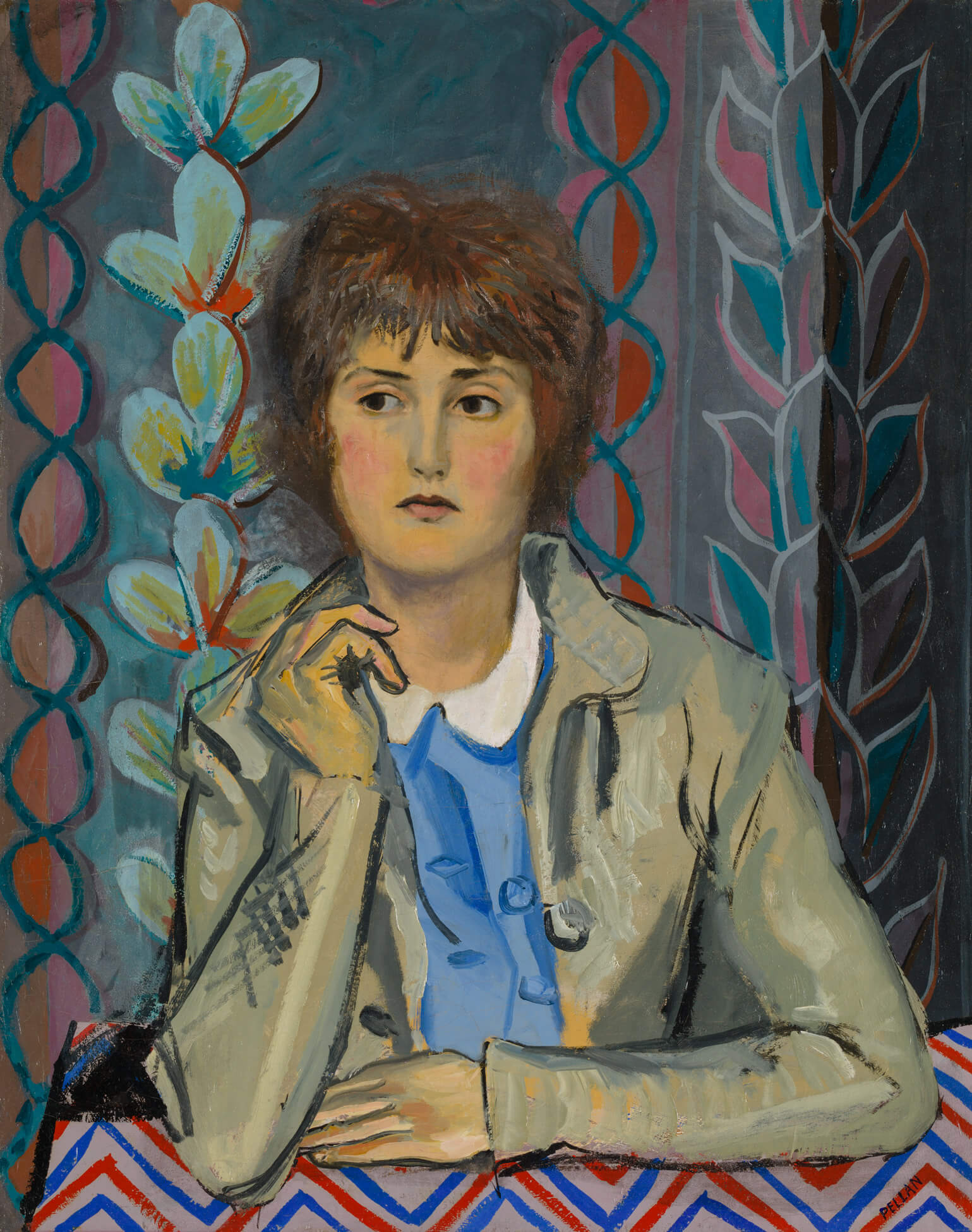

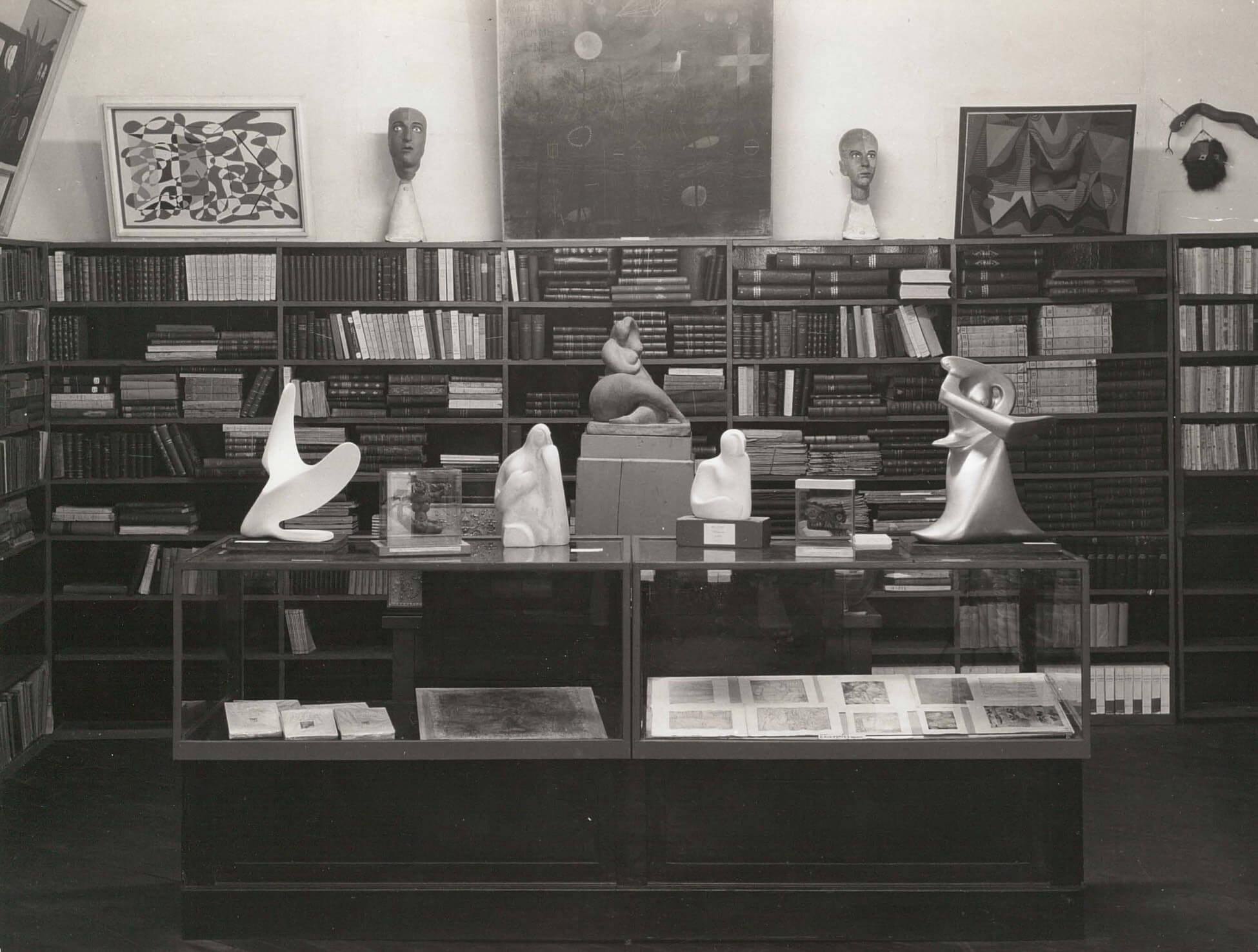

Against this political backdrop, in 1940 the Musée de la Province mounted the artist’s first solo exhibition, Exposition Pellan, under the patronage of provincial MLA Henri Groulx. While Pellan had regularly participated in salons at the École des beaux-arts during his time in Paris, the public in Quebec had only a vague sense of his art. As a result, this show marked the first opportunity for many of those around him to directly engage with his daring forms, colours, and compositions, which featured “elements of style from most of the modern masters.” Among the works on display were Jeune fille aux anémones (Girl with Anemones), c.1932, Jeune fille au col blanc (Young Girl with White Collar), c.1934, La table verte (The Green Table), c.1934, and Fleurs et dominos (Flowers and Dominoes), c.1940.

The 161 paintings, sketches, drawings, gouaches, and aquarelles included in Pellan’s Musée de la Province exhibition introduced Quebec to the “liveliness” of the “new” French art, and challenged the conformity of creative norms in the province. While the show was met with some enthusiastic reactions, only a few reviews were published after it opened. Moreover, many viewers were unsure whether to admire or condemn Pellan’s aesthetic. Among those confounded was painter Marc-Aurèle Fortin (1888–1970), who, upon surveying the exhibition, declared that the work on display confirmed his sense that he lived in a “century of follies.”

It was only after the show moved to Montreal later that year that artists such as Jean Paul Lemieux (1904–1990) spoke up on Pellan’s behalf. Although he recognized that the abstract compositions might be challenging for many visitors (as works on display in Montreal included Pensée de boules [Bubble Thoughts], c.1936, and Mascarade [Masquerade], c.1939–42), Lemieux encouraged people to look closer. One could be surprised, unsettled, or even disconcerted by Pellan’s paintings, but the artist’s avant-garde approach also provided the opportunity to spark the imagination and expand the horizons of creative possibility.

Art historians have identified this exhibition as one of critical impact in Quebec. François-Marc Gagnon (1935–2019) argued that through Pellan, “Canadian painting was catching up with international movements.” To be sure, despite art historian Dennis Reid’s assertion that the artist “was received as a returning hero,” Pellan’s paintings were not universally embraced; he continued to grapple with many prevailing prejudices about modern art. Although fierce in his stance against academic traditions, Pellan realized that he needed to build bridges between accepted norms and the new approaches he proposed through his art. This attitude was crucial in defending his modernist expression in a society that was only just beginning to embrace new tendencies.

Legacy as a Teacher

In 1943, Pellan accepted a teaching position at the École des beaux-arts in Montreal, perhaps partly motivated by the desire for a steady and reliable income. He openly denounced the rigid atmosphere of the school and the restrictions imposed on the students. By 1952, when he reached the end of his tenure, the institution boasted an atmosphere that was far more liberal and open.

According to Pellan, art in itself wasn’t teachable, because it encompassed questions of “personal sensibility, imagination, research and invention.” Instead, he sought to create an environment in which student creativity could flourish, explaining, “I did my best to come up with a free class, because I think it necessary if one wants students to do sincere work. For my part, I give them free rein to do what they want. What really matters is that a student finds himself, that he is able to express his personality in full.” He was careful not to impose any specific aesthetic, not even his own style, on those who took his classes.

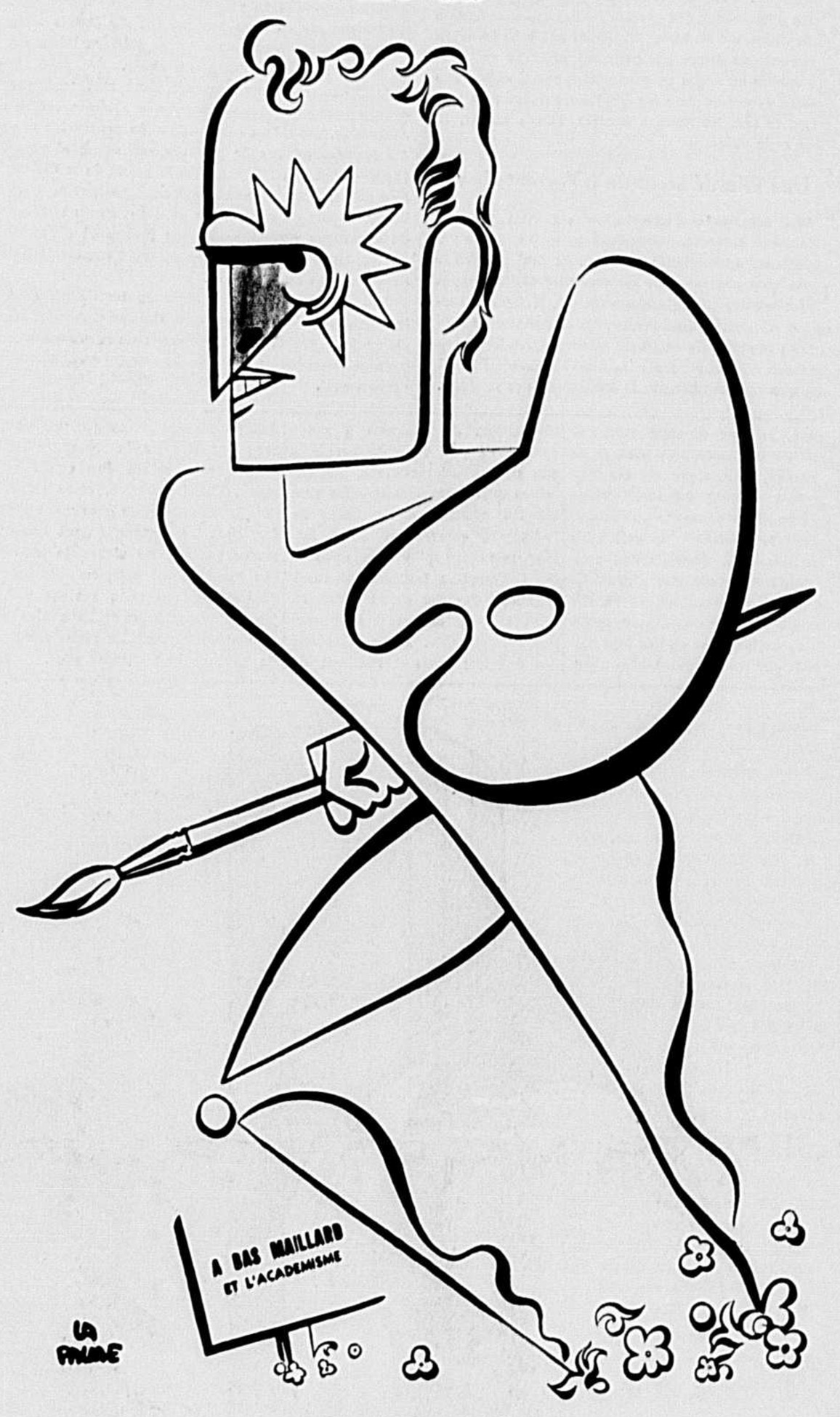

Pellan’s ideas on art and teaching provoked conflict within both the faculty and the student body. He and the school’s director, Charles Maillard (1887–1973), experienced some tension from the outset; their difference of opinions came to a head in 1945. While surveying the annual Salon de l’École des beaux-arts shortly before it opened, Maillard demanded that two pieces by Pellan’s students be taken down for “moral reasons”—one painting of a nude by Mimi Parent (1924–2005), and one that was intended as a parody of Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452–1519) The Last Supper, c.1495–98. The director insisted that the exhibits needed to be “irreproachable.” Instead, Pellan advised his students to amend the specific aspects that seemed to disturb Maillard’s sensibilities. The works were ultimately removed from the show, despite Pellan’s objections.

That decision led to a protest by members of the student body, who opposed “narrowness, [special] interests and authoritarianism in art.” The official student association (MASSE) opined that the uprising compromised “the good reputation of all [the association’s] members.” But the mainstream press saluted the students’ actions as belonging to a generation frustrated by cultural dictatorship and the reactionary spirit that still reigned at the school.

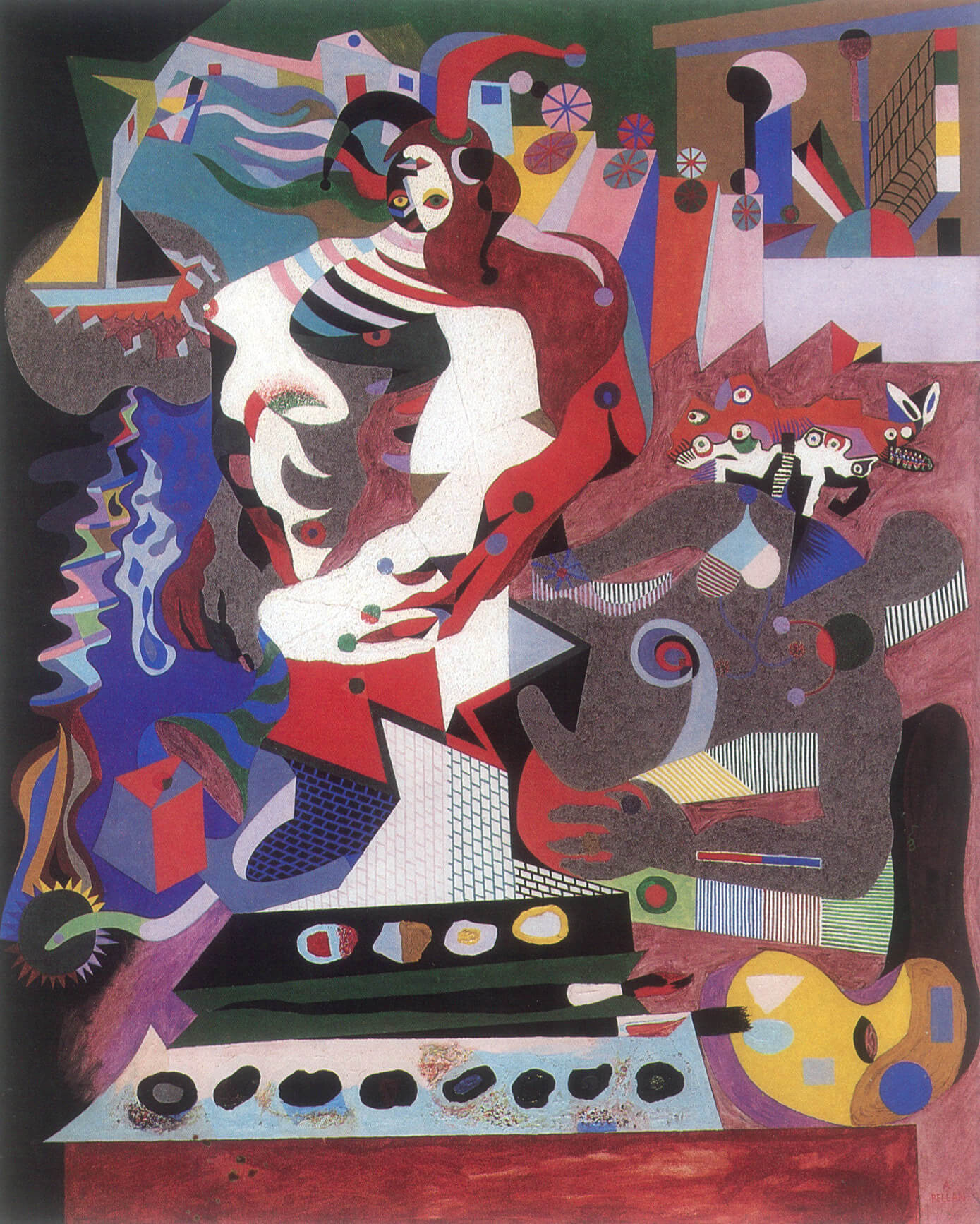

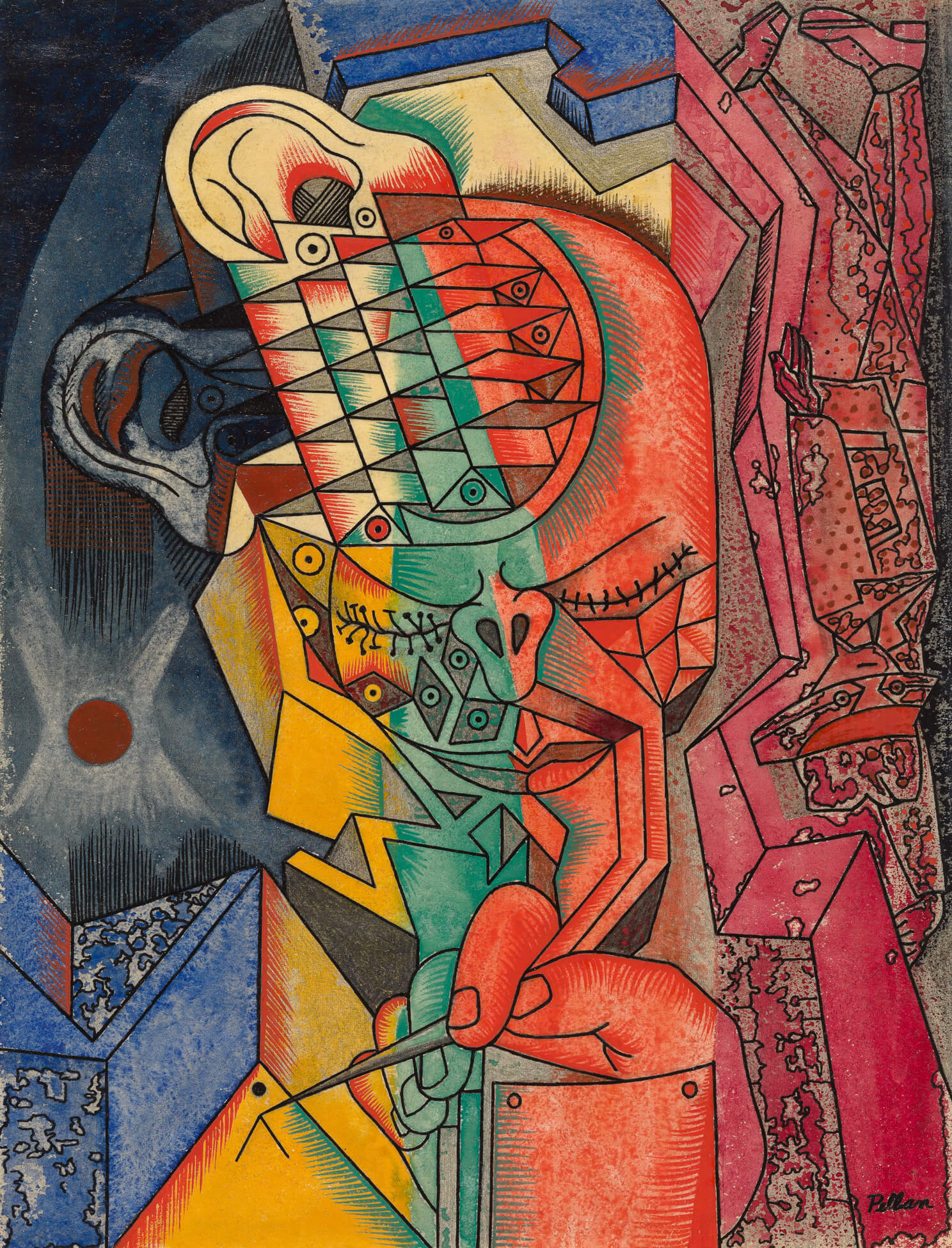

In a personal statement, Pellan declared, “To my knowledge, this is the first time censorship of this sort has been imposed in a fine arts school. M. Maillard deems the incident finished. I want to tell him that it is actually not finished.” And as it turned out, the controversy was not yet resolved. The Affaire Maillard, as it is known today, became a key event in the gradual cultural revitalization of Quebec society during the 1940s. In the end, Pellan and his students emerged victorious—and he created a painting inspired by the incident, Surprise académique (Academic Surprise), c.1943. An allegorical take on the event, the canvas shows a Surrealist-inspired scene with tools for painting in the foreground, along with architectural elements and a central character who resembles a harlequin. This figure’s head is positioned upside down; it seems to have recoiled in a state of panic. The composition is chaotic, a riot of disparate elements in an uneasy relationship to one another. Although the painting is intended to convey discomfort, it also contains an element of whimsy, signalling Pellan’s amusement at the situation. In the wake of the scandal, Maillard resigned, opening up new possibilities for the École des beaux-arts.

Pellan vs Borduas

In the history of Quebec art, Pellan is known as a figure who heralded the advent of modernity as part of a wave of social and cultural progress. But he was not alone in this endeavour. Another name that became synonymous with modernism is that of the painter Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960). While Borduas’s outspoken political stance made him a symbol of the separatist movement during the Quiet Revolution, Pellan, who found most arguments in favour of separation to be one-sided and excessively dogmatic, remained on the sidelines of these discussions. (His moderate views were out of step with the political climate at the time.) Nevertheless, Pellan’s critique of tradition and commitment to innovation were instrumental in setting the stage for modern art to flourish in Quebec. Indeed, it has been said that Pellan’s actions “became the catalyst” for the radical change inherent to Borduas’s work and ethos.

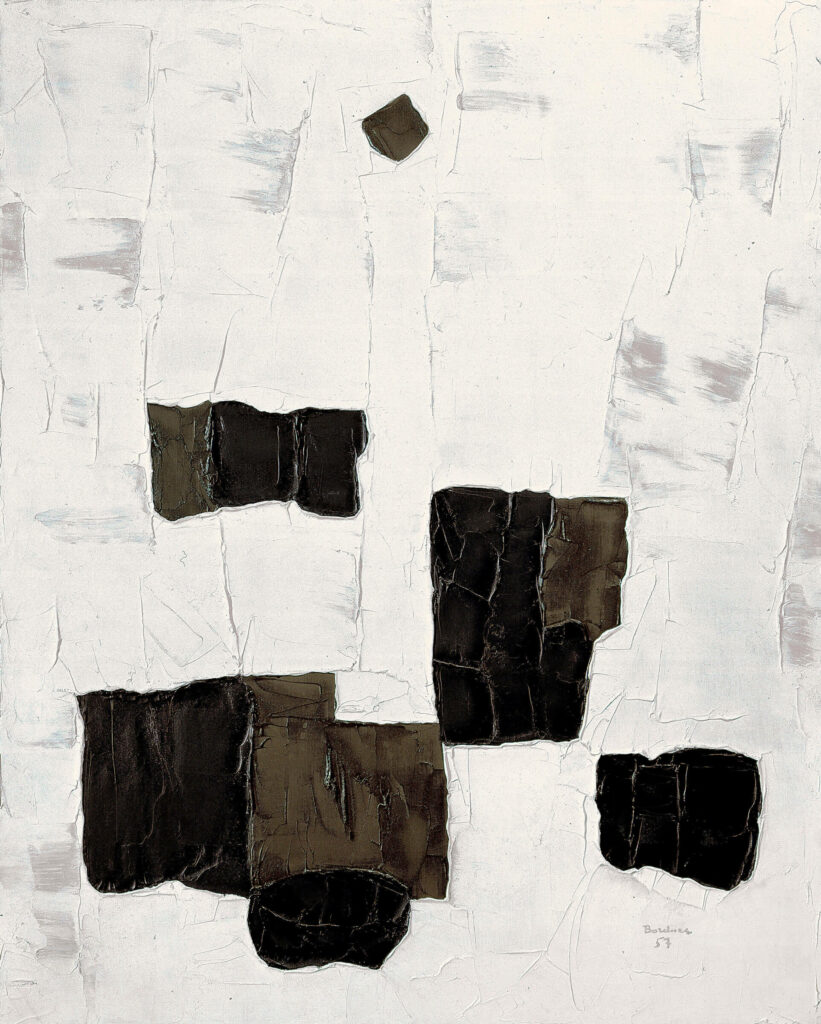

Although Pellan and Borduas originally worked in tandem to confront old ideologies and challenge rote allegiance to convention, hostility developed between the pair sometime in the early 1940s. This antagonism would endure for the rest of their lives, although its exact source is hard to pinpoint. Some have defined the tension as a stylistic one—the two men had radically different approaches to artmaking, a contrast that can be seen if one compares Pellan’s L’homme A grave (Man A Engrave), c.1948, and Borduas’s The Black Star, 1957. Writer Claude Gauvreau (1925–1971), on the other hand, suggested the rupture happened after Pellan accepted the position as professor at the École des beaux-arts in 1943. Pellan was not only considered a traitor to the modernist cause, he was also condemned as a naive pawn in director Charles Maillard’s effort to improve the image of the school. Both Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art founder Guy Robert (1933–2000) and philosopher François Hertel attributed the conflict to jealousy, noting Borduas’s temperament as a major factor. Curator Germain Lefebvre, while more sanguine in his assessment of Borduas, also described the feud as one of polarized personalities.

For art historian François-Marc Gagnon, the animosity between the artists was symptomatic of two antithetical ideologies. Through his more traditional portraits and Canadian landscapes, such as Enfants de la Grande-Pointe, Charlevoix (Children from Grande-Pointe, Charlevoix), 1941, and Cordée de bois (Cord of Wood), 1941, Pellan aimed to make the efforts of a modern painter accessible to both seasoned collectors and general audiences. This compromise was unthinkable for Borduas, who sought “not to tame the public to modern art,” but “to move forward into the unknown.”

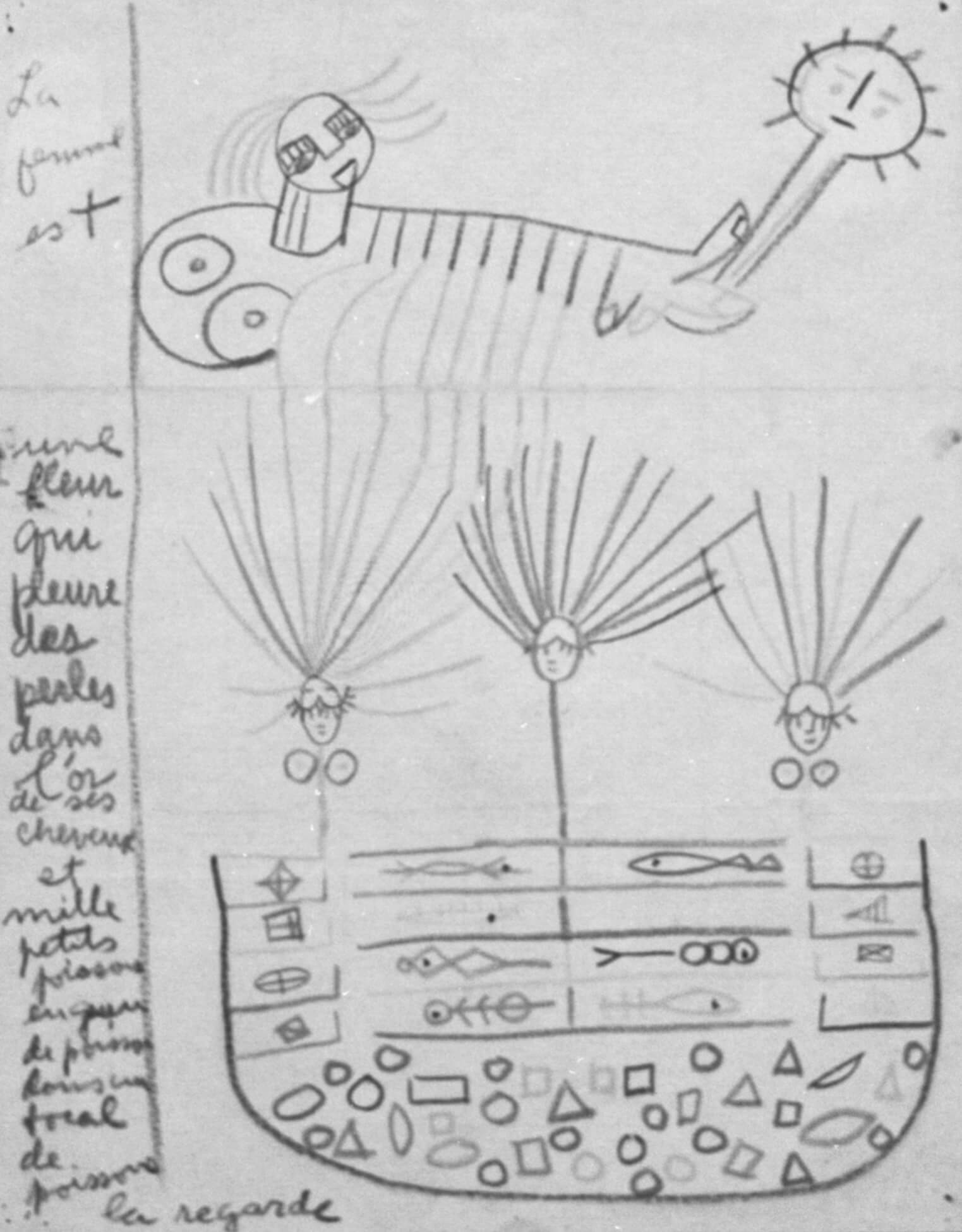

There is truth to all of these theories. However, two essential issues seem to be at the heart of the artists’ discord. First, Pellan opposed the manner in which Borduas had adapted the Surrealist concept of automatism—a process in which thought is expressed “free from any control by reason, independent of any aesthetic or moral preoccupation.” In Pellan’s opinion, no single technique should stand as an end in itself. He did acknowledge the potential of automatism, but believed that artists needed to expand on the basic concept. For him, automatism served as a preparatory tool, on whose basis pictorial problems were to be elaborated. This interest is evident in works such as La pariade (The Pairing), 1940–45, where Pellan developed his composition in a manner that allows hybrid creatures to flow together.

Perhaps even more importantly, Pellan was highly critical of how Borduas presented automatism as the only innovative school of thought. Pellan didn’t believe that there was one single truth, but rather a range of equally valuable truths. According to him, such variety was necessary to prevent stagnation and to avoid simply re-establishing a kind of academic art.

Prisme d’Yeux

Pellan had no desire to be formally affiliated with any particular art movement, and he welcomed a multiplicity of viewpoints. Prisme d’Yeux, a group largely founded on his initiative in 1948, was supposed to counterbalance the Automatistes, an experimental movement led by Paul-Émile Borduas. It encouraged diversity of expression, even encouraging the open sharing of opinions that directly opposed one another. The group’s main objective was liberty: as they stated in their manifesto, “we seek a painting [practice] free from all accidents of time and place, and of restrictive ideology; and conceived without the intrusion of literary, political, philosophical, or other influences which can adulterate its expression and sully its purity.” In their first exhibition, held at the Art Association of Montreal, Pellan showed Femme d’une pomme (Lady with Apple), 1943.

Members of the group were convinced that to defend artistic freedom, it was essential to support all styles and theories in art, even contradictory ones. This, along with their disdain for politicized art, was key to their ideology. Because the original manifesto has disappeared, it is not possible to verify all the signatories, but some confirmed members of the group were Mimi Parent, Jean Benoît (1922–2010), Albert Dumouchel (1916–1971), Pierre Garneau (b.1926), Jeanne Rhéaume (1915–2000), Jacques de Tonnancour (1917–2005), Léon Bellefleur (1910–2007), and Louis Archambault (1915–2003).

Although the group ostensibly stood for freedom, its members refused to abandon established ethical norms. Unlike Refus global, the Automatistes manifesto published by Borduas that year, which called for everyone to “permanently break with every habit of society [and] to disengage from its utilitarian spirit,” Prisme d’Yeux did not pose a threat to the socio-political status quo. And because the group’s innovations seemed to exclusively target the domain of art, they were lauded in the contemporary press, where their endeavours were interpreted as sincere and emblematic of the “diversity of human experiences.” Borduas, on the other hand, was presented as an egotist whose opinions threatened the fabric of society. Prisme d’Yeux initially seemed to win the battle to become Montreal’s leading art group: aside from a few negative responses, most critics encouraged the collective to expand its efforts.

The “Conspiracy of Silence” and Pellan’s Legacy

While Canadian critics initially considered abstraction a “marginal phenomenon with no future prospects,” by the 1950s the unorthodox qualities of this approach were seen as the only way to free art from prevailing aesthetic strictures. That notion deeply influenced how Pellan’s oeuvre was perceived. Although works such as La spirale (The Spiral), 1939, illustrate his engagement with abstraction, Bouche rieuse (Laughing Mouth), 1935, is an example of how the artist placed limits on purely nonrepresentational art. Meanwhile, the liberal francophones who had initially gravitated toward Pellan’s group, Prisme d’Yeux, developed a new appreciation for Paul-Émile Borduas and his approach to abstraction. The apolitical stance that had previously drawn supporters to Prisme d’Yeux became less appealing in the years before the Quiet Revolution—a period of intense socio-political and cultural change in Quebec. At the same time, many were galvanized by Borduas’s radical critiques of the ideological foundations of French Canadian society, which had, just years earlier, scandalized authorities and the press. As a result, Pellan became “more or less rejected by Quebec’s intelligentsia, who swore by the Automatistes.”

Pellan felt as though he’d been relegated to the fringes; in later interviews, he spoke of a “conspiracy of silence” in which he was a specific target, one that was more broadly directed toward anyone not affiliated with the Automatistes. But quantitative assessments of articles written about the artist’s work and activities make it clear that, while he received relatively fewer mentions during this period than he had in the 1940s, there was no dramatic decline in his press coverage. Pellan’s achievements were publicized, his exhibitions were promoted, and his controversial show at City Hall in 1956 sparked a larger discussion about censorship, with many speaking up in the artist’s favour.

Although Pellan feared the controversy with Borduas overshadowed his legacy, the significance of his modernist explorations remains undisputed. He is known for radical paintings such as Sans titre (Untitled), 1942, and Le petit avion (The Small Plane), 1945, the latter of which received an honourable mention at the Art Association of Montreal in 1949. His work continued to evolve and was widely exhibited until his death in 1988. Today, Pellan is recognized for his contribution to freeing a young generation from “an era of lethargy where the stiff coldness of academism was only equaled by an outdated Picturesque style.”

Pellan at International Exhibitions

In the first half of the twentieth century, Canadian artists were rarely known beyond the country’s borders. During the Exhibition of English-American Painters of Paris in 1935, French critics questioned whether Canada could be said to have its own art. Pellan, one of two artists chosen to represent the country in the show, was lauded by European collectors and the press—effectively providing an emphatic answer to that question.

While Pellan absorbed the European trends he encountered in Paris between 1926 and 1940, he transformed these influences through a “North-American/Quebecois prism”; this personal interpretation of his source material became even stronger over time. He remained connected to his origins throughout his long sojourn abroad, a shining example of an artist who embraced the possibilities of modern (European) art while cherishing his own (French Canadian) traditions and culture. Because of this hybrid approach, Pellan helped establish Canada as part of the international art scene, while underscoring the country’s unique national identity.

Pellan’s work became an important factor in the country’s cultural politics after the Second World War. The most striking example is his inclusion in the first Canadian section at the 26th Venice Biennale in 1952 (along with Emily Carr [1871–1945], David Milne [1882–1953], and Goodridge Roberts [1904–1974]). Canadian officials firmly believed that art and culture had important roles to play in international affairs. As part of “larger systems of artistic practice, markets and commercial relations, local and national economic development and political activity of various kinds,” biennials in general provided excellent opportunities to present a strong national identity on a global stage. Since its inception, the Venice Biennale has emphasized themes of nationhood, and with the country’s inclusion in 1952, Canada finally took its “place with most of the other nations of the free world in this assembly of the arts.” In addition to helping define what Canadian contemporary art could be, Pellan contributed to the spread of artistic theories developed in Canada. This phenomenon continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s, as the Ministry of Cultural Affairs enthusiastically supported Pellan’s exhibitions in major European cities as part of Quebec’s effort to assert its unique identity.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements