Born in Quebec, Alfred Pellan (1906–1988) spent his formative years in Paris, returning to conservative French Canada in the 1940s with revolutionary ideas about modern art. Influenced by movements such as Cubism and Surrealism, he developed an eclectic approach to painting and fought to free art from dogmatic thinking. While Pellan was an energizing force in Quebec culture, he was also no stranger to conflict, and his life was as daring and colourful as his canvases. His influence can be seen everywhere from gallery walls to city murals; his spirit lives on through the work of creative rebels who defy convention in their art.

Childhood and Early Years

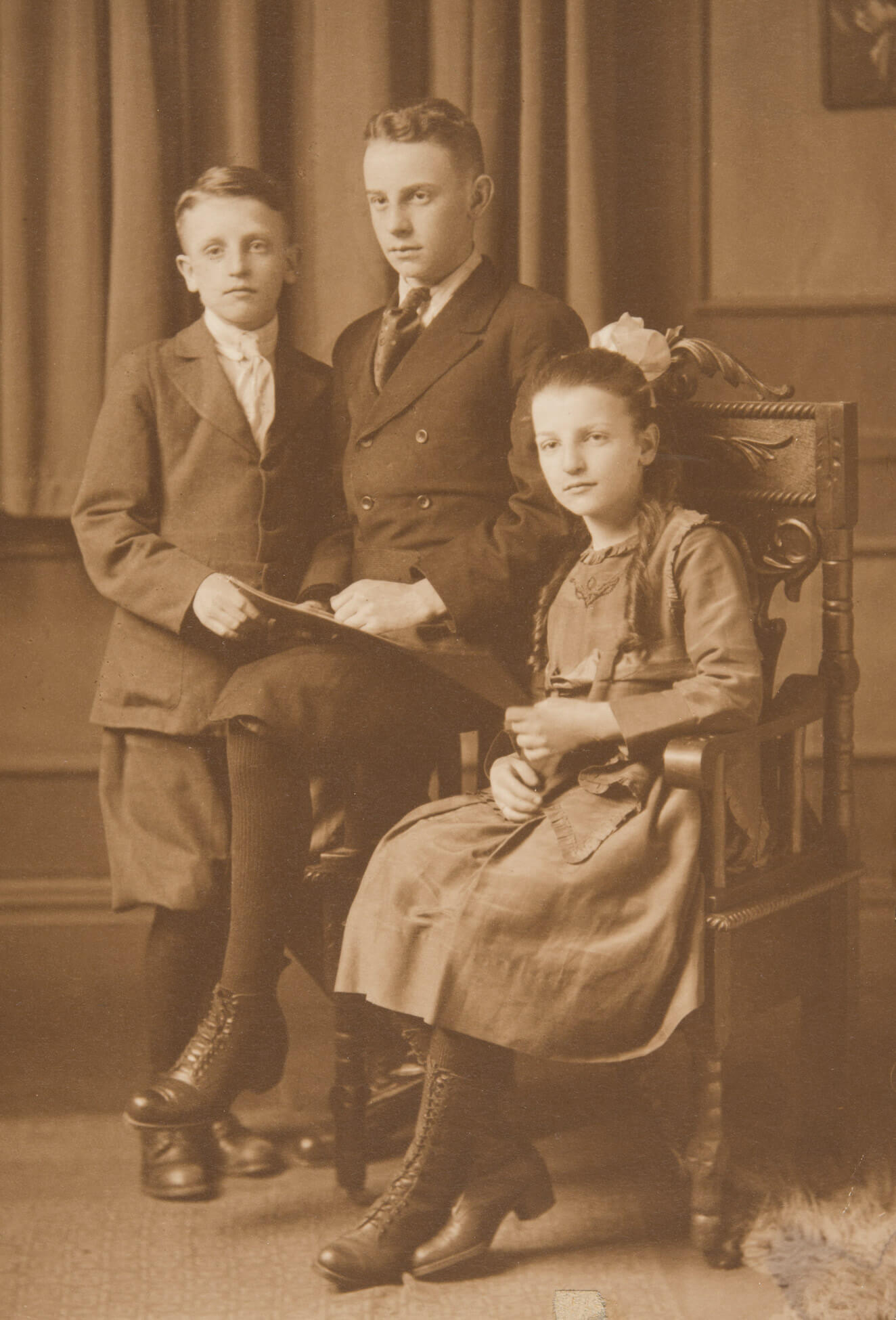

The artist was born in 1906 in the Saint-Roch quarter of Quebec to Alfred Pelland, a Canadian Pacific railway engineer, and his wife, Maria Régina Damphousse. Pellan—he dropped the “d” from his last name in his twenties—had only vague memories of his mother, who passed away in 1909. His father, who raised Pellan and his siblings, Réginald and Diane, on his own, sought to nurture the boy’s creative talents. Later in life, Pellan would recall moments when he required help to continue with his work, and was deeply grateful that he could always count on his father’s unfailing support.

Pellan was drawn to the arts from an early age—so much so that he had little interest in other subjects. As he recalled in 1959, “my passion for sketching was so strong that my head stubbornly refused to take in lessons of Latin and Grammar.” At fourteen, Pellan found some paint and brushes his father had bought and abandoned. Intrigued, he created his first paintings—one of which, Les fraises (Strawberries), 1920, survives to this day.

“The discovery of that box of paint awakened in me an irresistible urge to colour, to bring to life with a brush what I saw,” said the artist in 1939. Convinced of his son’s talents, Pellan’s father drove him to the recently opened École des beaux-arts de Québec. There, the young artist showed his early attempts to the director, Jean Bailleul, who accepted Pellan’s application and declared: “Maybe we’ll make an artist out of you.”

The École des beaux-arts de Québec was founded in 1922 as part of substantial scholarly reforms launched by Louis-Alexandre Taschereau’s Liberal government in the 1920s. Provincial leaders were interested in expanding the education system in the wake of the social changes brought about by industrialization; they were also keen to develop a specifically French Canadian culture of intellectual elites. The École stood apart from the trade schools where graphic design was taught, underscoring the fact that studying to be an artist was in its own unique category. Even so, students at the École took workshops where they received practical training, with the intention of equipping the future artists to produce commercial and industrial work.

Pellan enjoyed the loose structure at the École, which offered students greater freedom despite its rigorous academic program. In addition to his studies in drawing and painting, he also explored sculpting and took classes in architecture. These opportunities informed his emerging artistic eclecticism, an approach that later encompassed working across various media. Bailleul, the school’s director, allowed Pellan to change classes at will, and told the concierge to let the young artist work in the studios after hours.

Pellan was still a student when his work began to draw attention. At the 1923 Salon de l’École des beaux-arts de Québec, he won first prize in the categories of painting, sculpture, drawing, and decorative arts. The same year, when the artist was only seventeen, the National Gallery of Canada purchased Coin du vieux Québec (A Corner of Old Quebec), 1922. At the school’s exhibition in 1925, Pellan came first once again in drawing, painting, and sculpture. The press made special mention of the young artist, noting that his still lifes showed “an outstanding sense of colour.” The following year, one of his portraits received accolades for the “quality of the drawing, the depth of colour, the harmony and accurate portrayal of the ensemble.”

In 1926, Pellan was awarded the province’s first scholarship; this allowed him to move to France, where he continued his studies over the next three years. He left for Paris in August with Omer Parent (1907–2000), his friend and fellow stipend recipient, and lived there until 1940.

Pellan in Paris

Upon his arrival in Paris in 1926, Pellan enrolled at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, as required by the scholarship he had received from the Quebec government. There he attended classes taught by painter Lucien Simon (1861–1945). Although Pellan was not particularly impressed by Simon’s art, which combined principles of Impressionism with the melancholy realism of painters such as Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), he enjoyed the experimental nature of the class. Simon encouraged the young French Canadian to reach beyond the school’s strict adherence to tradition and instead develop his own artistic expression. “I loved the freedom,” Pellan recalled in 1967. “I wanted to train myself, alone.”

Besides his mandatory classes, Pellan began sitting in on sessions at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière (where Simon happened to be a founding teacher) and the Académie Colarossi. He often walked through Paris, fully immersing himself in the atmosphere. As Canadian poet Alain Grandbois observed, “there was in Montparnasse my friend Pellan, who dove into art like one would into a swimming pool.” Pellan had encounters with many artists, including Max Ernst (1891–1976), Fernand Léger (1881–1955), Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), and Joan Miró (1893–1983); he became friends with the Surrealist writer André Breton (1896–1966), who would come to play a key role in his career.

In 1932, Pellan visited the Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, and was impressed enough to return several times. The 1937 Van Gogh retrospective, La vie et l’œuvre de Vincent van Gogh, organized as part of that year’s World’s Fair, wholly entranced Pellan, who later claimed, “I left as if I were drunk.” Pellan was fascinated by van Gogh’s daring compositions and powerful use of colour, and admired the artist’s efforts to reinvent existing modes of expression.

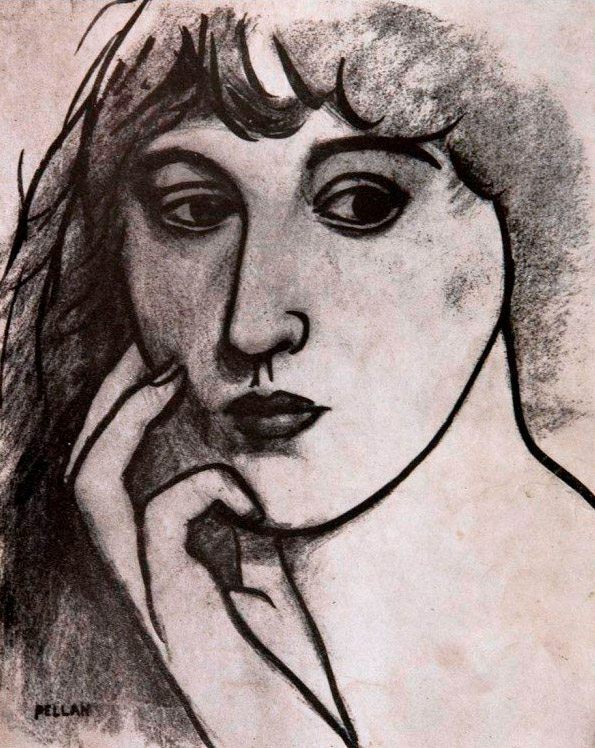

While Bailleul had accorded Pellan a certain amount of freedom at the École des beaux-arts de Québec, there had been little opportunity to study progressive, contemporary works. In France, Pellan realized the limits and constraints of what he had been taught: previously, he noted, he had “only painted things that were academic and realist,” whereas in Paris, he “discovered modern art; it was love at first sight. From this time forth, it was the only nourishment that could sustain [him].” Reflecting on that epiphany in 1967, Pellan said he felt “compelled to start all over,” which was “quite dramatic.” Comparing works like Coin du vieux Québec (A Corner of Old Quebec), 1922, and Portrait de femme (Portrait of a Woman), c.1930, with La table verte (The Green Table), c.1934, or Hommes-rugby (Footballers/Rugby Players), c.1935, it is clear how quickly his work changed during this period.

Pellan’s painting began to turn heads in Paris. His work earned first prize at a show featuring all of Lucien Simon’s students in 1930. In a review of the exhibition, Claude Balleroy criticized Simon’s heavy influence on almost all the works being shown, but lauded Pellan’s seductive still lifes, which he claimed demonstrated “original talent.” In contrast to his teacher’s melancholic paintings, Pellan’s colourful works, such as Les tulipes (Tulips), 1934–35, represented a joyful exuberance that connected with critics.

In 1935, Pellan was part of a group exhibition at the Galerie de Quatre-Chemins, an event French art critic Jacques Lassaigne (1911–1983) called a “remarkable debut.” That year also marked his first solo show at the Académie Ranson (founded by French painter Paul Ranson [1861–1909] in 1908, where the art group Les Nabis famously met), which prompted another critic to laud the “robust talent” that distinguished the artist from the rest of his generation.

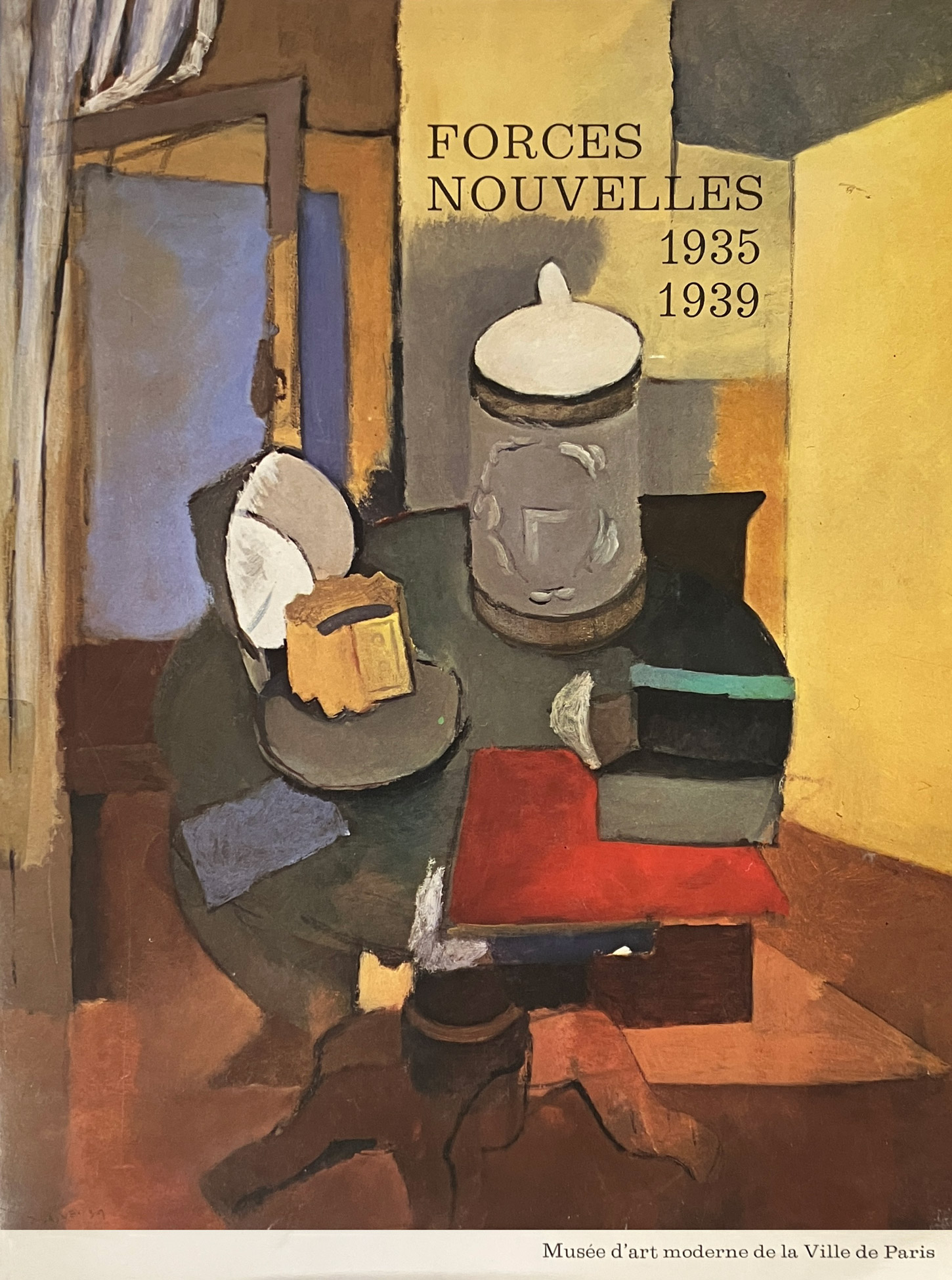

Pellan was briefly affiliated with Forces nouvelles, the fringe art movement founded in 1935 by artist and critic Henri Hérault (1894–1981). Not satisfied by modern art’s experimental ideas and methods, Hérault called for renewed reverence for the order of the past. The group’s goal was to develop a living art inspired by tradition; they strove for a form of intensified realism centred on drawing, which they believed was the best technique for understanding and representing nature. However, this approach carried with it the possibility of privileging a new kind of academic art, a danger Parisian critics did not fail to notice. Whether it was because he feared another restrictive approach or perhaps simply out of a desire to continue on his solo path, Pellan left Forces nouvelles after its first exhibition at the Galerie Billiet-Pierre Vorms in 1935.

Pellan was more comfortable at the first Salon d’art mural in 1935, which was open to artists who were able “to link painting with architectural values and uses.” He won first prize for his Cubist-inspired Instruments de musique – A (Musical Instruments – A), 1933. Despite having received critical recognition, it was only in 1939 that he obtained commercial representation from the bold and venerable Galerie Jeanne Bucher, alongside an extraordinary group of big-name modern artists, including Georges Braque (1882–1963), Max Ernst, Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso, Jean Arp (1886–1966), and Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966).

Throughout his time in France, Pellan continued to show his work in Canada. In 1928, he sent a collection of 170 drawings to be included in the seventh annual salon of the École des beaux-arts de Québec. In May 1935, he contributed to the first Salon des Anciens, an exhibition intended to highlight the efforts of the school’s alumni. A year later, Pellan’s father urged him to apply for a position as a professor at the École des beaux-arts de Québec, an undertaking that required the artist to travel back to Canada. As part of the process, Pellan was asked to produce a number of paintings so that the jury could assess his capabilities. Unfortunately, his modernist-inspired ideas and provocative works (like Peintre au paysage [Artist in Landscape], c.1935), as well as the company he kept in Paris, were considered undesirable qualities for a prospective teacher.

Even though there was a significant shift within Canadian art during the 1930s, Quebec institutions were still not open to experimental forms. The education system was controlled by a clergy anxious to avoid anti-Catholic influences, and the paternalistic regime was determined to preserve traditional social and aesthetic values. The jury that assessed Pellan’s application felt that he was “too dangerous,” and declared “it was absolutely impossible for him to think he could become a professor in Quebec.” As artist Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942), a member of the hiring committee, noted, “You are modern, you are doomed.”

Pellan was disappointed by his closed-minded compatriots and fellow artists, but delighted that he was able to return to France. In 1937, Nature morte à la lampe (Still Life with Lamp), 1932, which had been rejected by the hiring committee, was bought by French politician (and future founder of the Cannes Film Festival) Georges Huisman (1889–1957) and art historian Robert Rey (1888–1964) to be included in the French national collection. The work was exhibited in the Jeu de Paume, making Pellan the second Canadian artist to receive that honour, after landscape painter James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924).

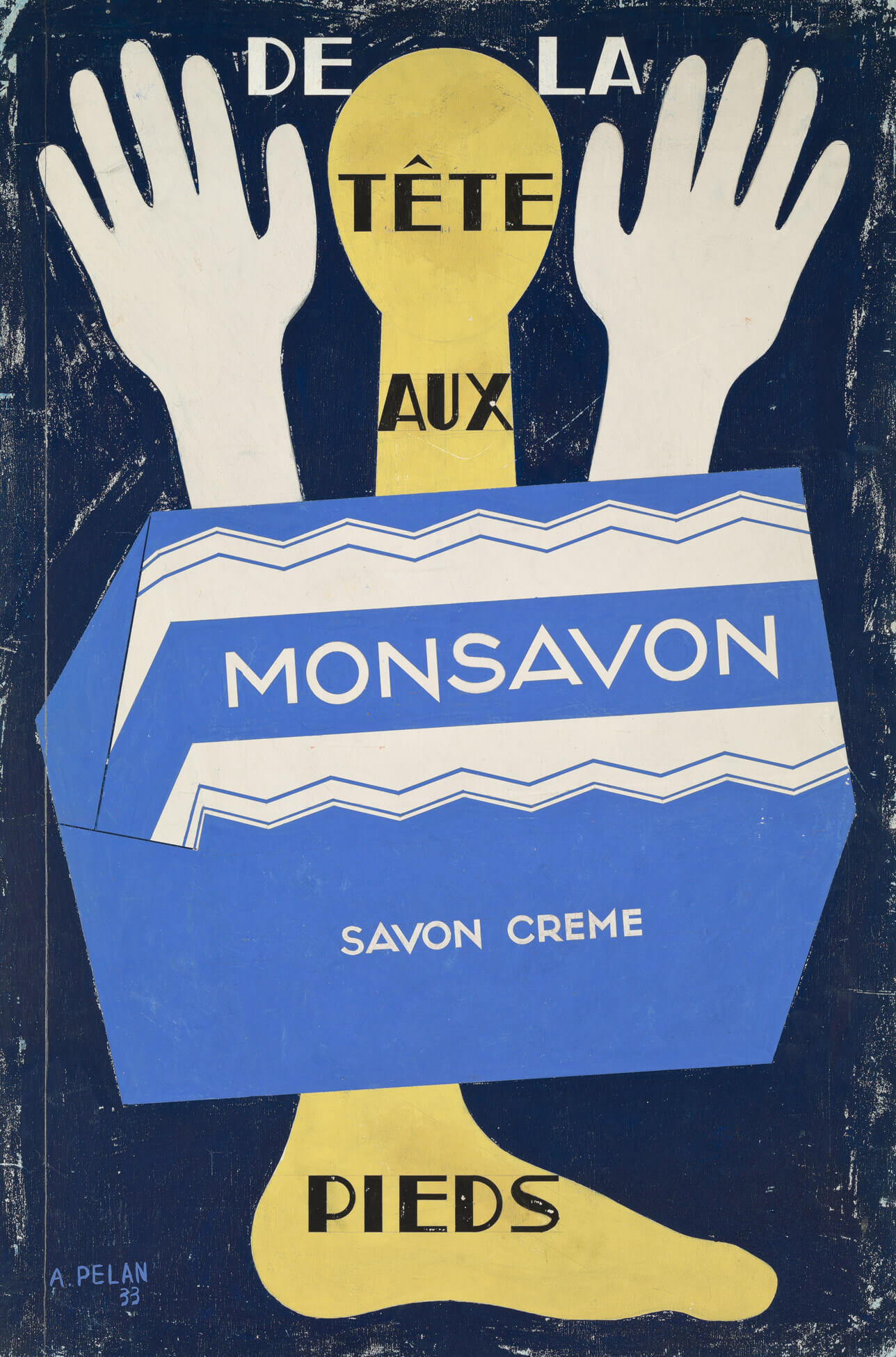

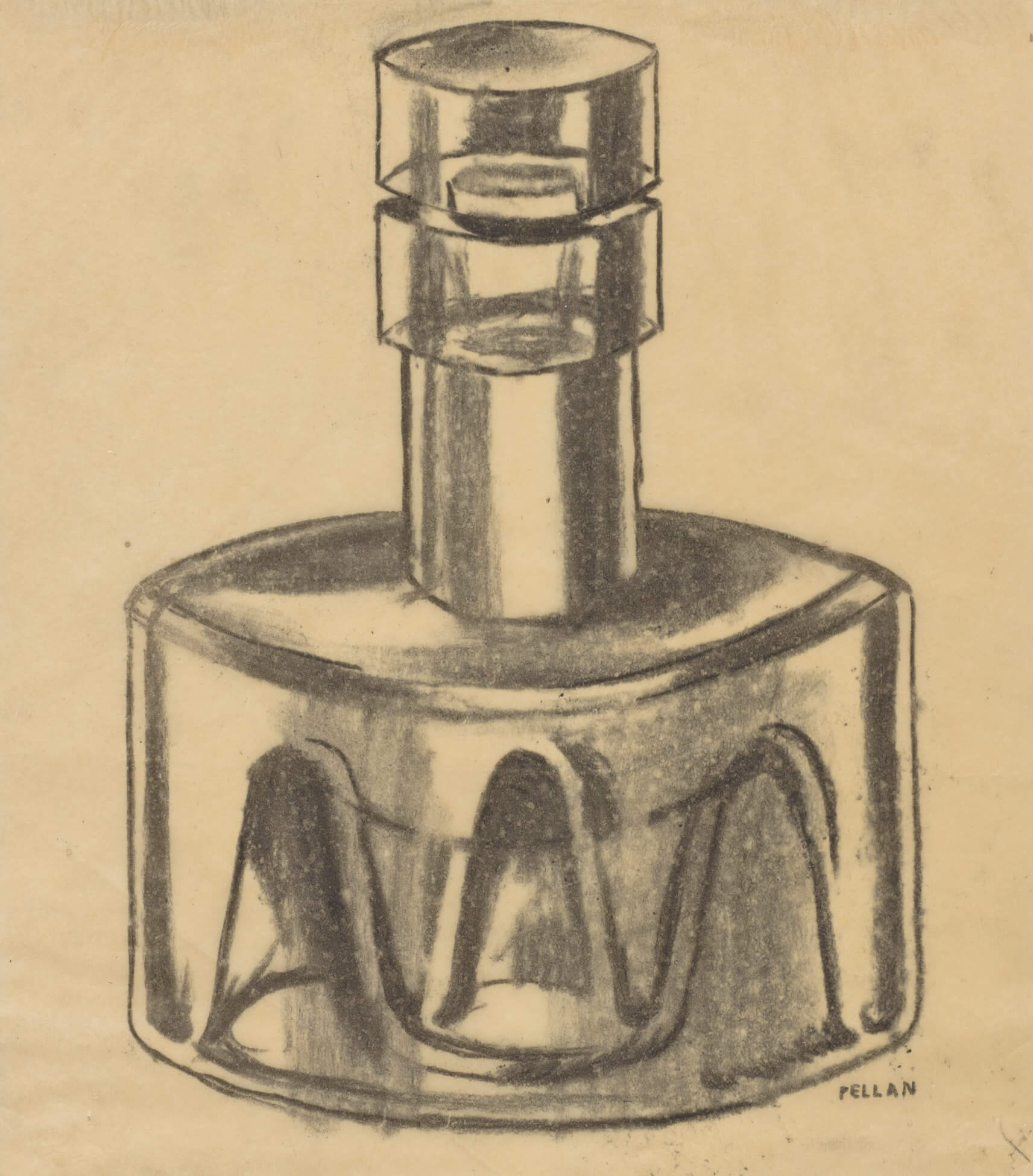

While Pellan’s original scholarship from the Quebec government had covered only a three-year term, the artist found ways to remain in Paris for fourteen years. Sales of his paintings were not sufficient to live on, so Pellan occasionally received financial help from his father, but he mostly took on odd jobs: he worked as a graphic designer and poster publisher, designed a perfume bottle for Revillon, and painted fabric for dresses by Schiaparelli (some of which were bought by the wife of painter Joan Miró). During this time, Pellan lived in parts of the city “where survival was easy with low rents and inexpensive meals aided by a further spirit of camaraderie often in reciprocation of a kind of action of a fellow artist a day or week before.” Unfortunately, the Second World War ended Pellan’s Parisian dreams. Shortly before the occupation, the Quebec government helped the artist travel home with more than four hundred paintings and drawings, though he had to leave his sculptures behind.

Outside the Montreal Mainstream

The Quebec that Pellan encountered upon his return from Paris in 1940 was not the province he had left in 1926. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Quebecois artists had yearned for change. Many wanted the cultural standards in French Canada to be elevated to the same level as that of other Western countries. Resisting the collective efforts of the Catholic Church and the provincial government to stem the process of cultural modernization, intellectuals fought to cast off retrograde traditions.

This movement included people like painter John Lyman (1886–1967), who founded the Contemporary Arts Society in 1939 to “give support to contemporary trends in art.” He united artists who sought “to affirm the vitality of the modern movement,” with the aim of destroying academicism and cultivating living art that encompassed many different styles. The group was open to all professional artists who were “neither associated with, nor partial to, any Academy.” In that atmosphere of change, Pellan, whose work was the “very embodiment of modern art,” according to art historian Dennis Reid, returned to Quebec a hero.

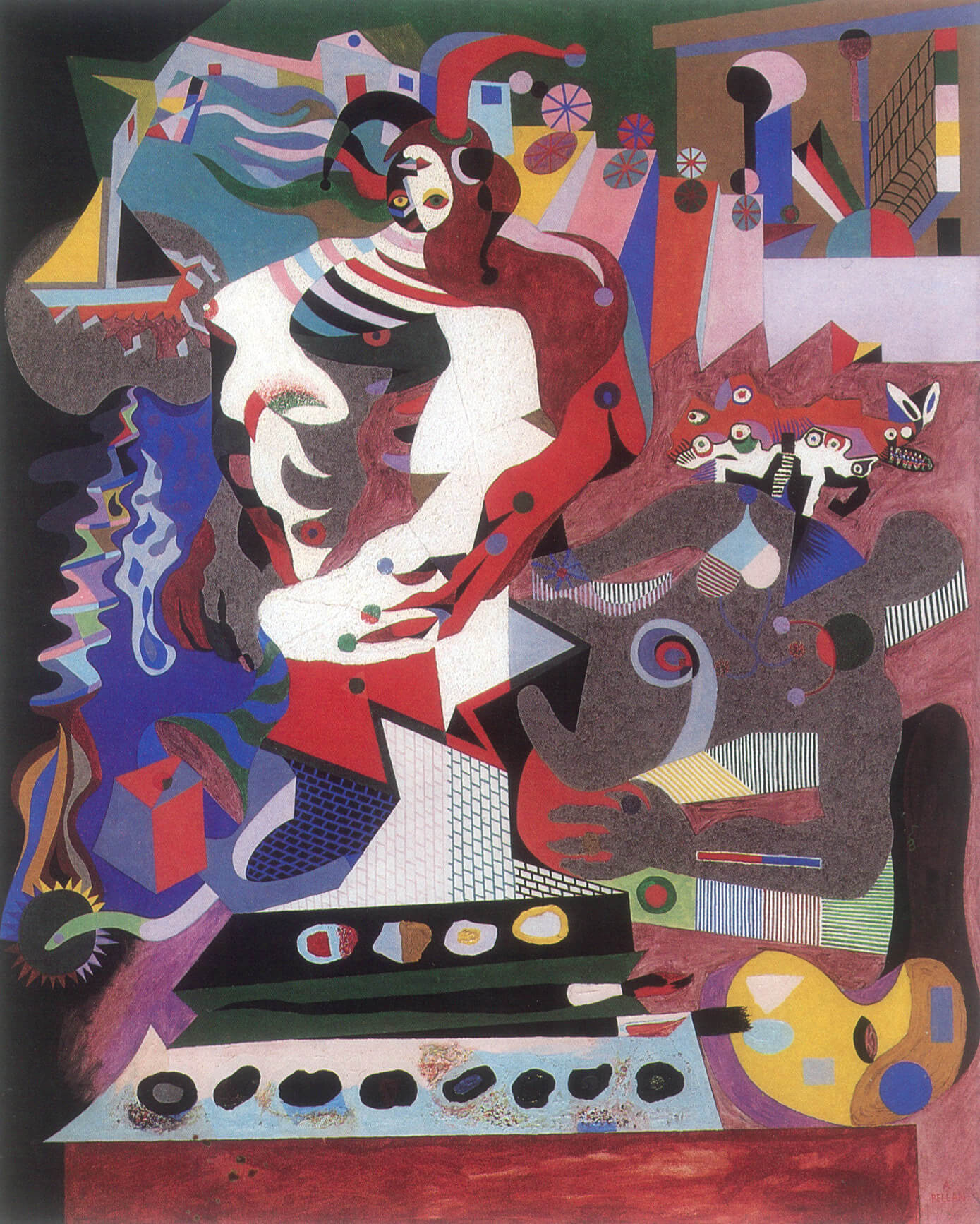

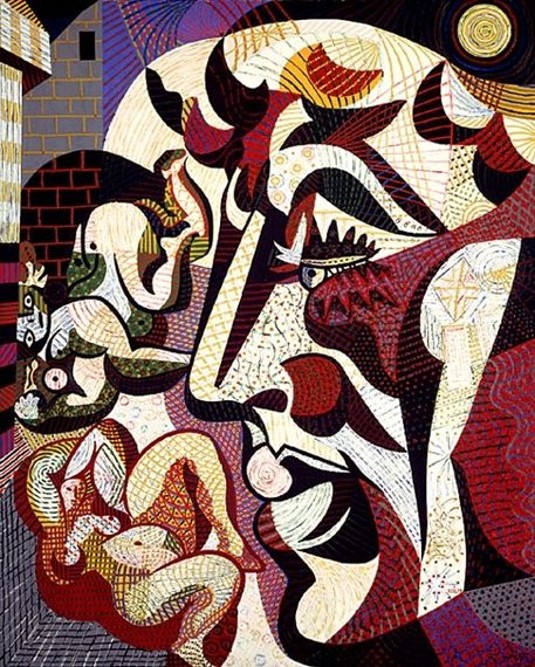

In June 1940, Pellan exhibited more than 161 works, reflecting a range of techniques from classical to highly modern, and encompassing much of his Parisian oeuvre, first at the Musée de la Province in Quebec City (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec), and later at the Art Association of Montreal. The show included such paintings as Mascarade (Masquerade), c.1939–42, La spirale (The Spiral), 1939, Jeune comédien (Young Actor), c.1935/after 1948, and Fleurs et dominos (Flowers and Dominoes), c.1940; to critics, this moment represented a turning point in Canadian art history because it triggered a profound “disturbance in the domestic conceptions of art.” Pellan catalyzed new discussions through his “Picasso-like drawings,” his still lifes “that evoked Braque,” his portraits “à la Modigliani,” and his sculptures of “modernist intensity.” The exhibition energized defenders of modernism and encouraged artists who had been trying to cast off established habits to push the boundaries of their work.

After that exhibition, Pellan moved to Montreal, sharing a studio with figurative painter Philip Surrey (1910–1990) until he found his own place a block away at 3714 rue Jeanne-Mance. Many young poets, painters, and musicians lived in the area, and Pellan renewed old friendships and widened his circle of confidantes, all of whom were deeply invested in progressive trends in art. Engaged with dynamic figures in the local art scene and sympathetic to the “idea of a living art independent of regional or didactic claims,” Pellan became a member of the Contemporary Arts Society, where he was welcomed with “open arms.”

Pellan participated in the first Exposition des Indépendants, organized by the refugee French priest Marie-Alain Couturier, in May 1941. Couturier sought to create a progressive art scene in which artists were not left to starve. The event was described by critic Rolland Boulanger as the very incarnation of liberated art and featured the work of eleven participants, including Surrey and Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960). Many critics specifically lauded Pellan’s paintings, which included Sous-terre (Underground), 1938, and Et le soleil continue (And the Sun Shines On), 1959 (first version c.1938). Even so, the lingering entrenchment of cultural conservatism in Quebec meant that there was still some public resistance to the avant-garde aspects of Pellan’s work. As one review pointed out, “Those of us who are not used to modern art and hardly understand the painting of Picasso and the other French celebrities, we cannot yet appreciate the value of the works of our fellow citizen, who is a painter more devoted to the painting than the subject.”

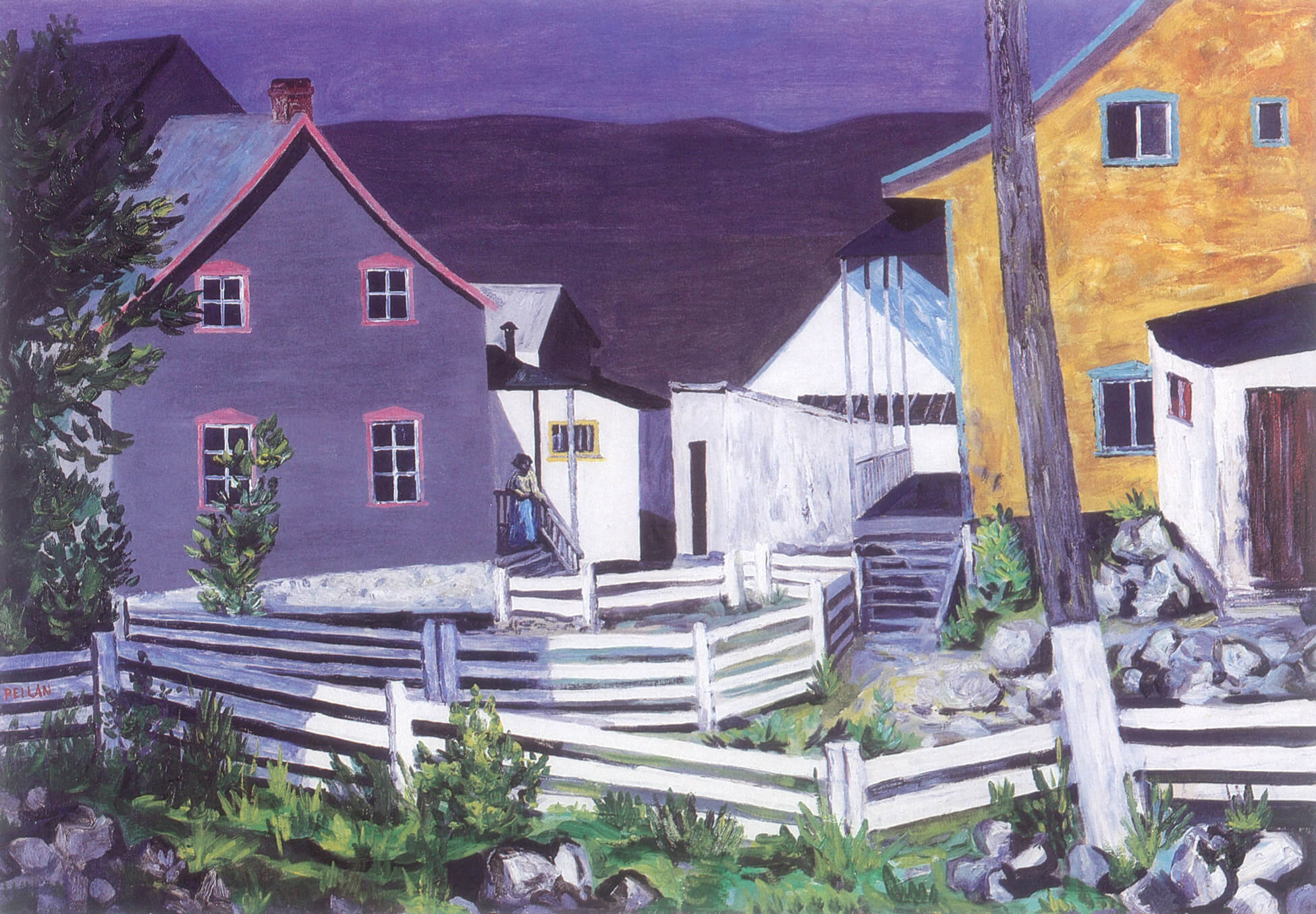

Aiming to appease conservative audiences, Pellan exhibited a series of portraits of young children and some startlingly realistic scenes, among them Maisons de Charlevoix (Houses in Charlevoix), 1941, and Fillette à la robe bleue (Young Girl in Blue Dress), 1941. These canvases were created during the summer of 1941 in Charlevoix, following an invitation from the artist couple Jean Palardy (1905–1991) and Jori Smith (1907–2005). As Pellan later noted, he was hoping to “build up confidence with a public that started to familiarize itself with [his] works.” That he received critical praise for “humanizing” his art may suggest that while these paintings conveyed “a new state of mind or maybe simply a concession to the ‘temperature’ of the new milieu,” the artist stayed true to himself.

In 1942, Pellan displayed another series of realist works in an exhibition at the Palais Montcalm in Quebec City. Once again, this selection was more easily accessible to the public than the “disconcerting” examples of his “non-representative paintings.” Four years later, he published Cinquante dessins d’Alfred Pellan (Fifty Drawings by Alfred Pellan). This endeavour had a clear purpose: because of Pellan’s distinctly modern sensibilities, there was a public misconception that the painter lacked drawing skills. The publication of this book provided compelling evidence that everything he did was based on a solid technical foundation. “Those who only know of his radiant and troubling eerie scenes,” wrote one of his critics, “can’t imagine the sombre depth and the dexterity of his charcoal, his pencil, or his pen.”

Throughout the early 1940s, Pellan continued to pursue new opportunities. In 1942, Jean Désy, the Canadian ambassador to Brazil, asked him to create a mural of Canada to be hung in the reception room at the Canadian Embassy in Rio de Janeiro. (As it turned out, this work was the first of many murals.) A year later, Pellan accepted a teaching position at the École des beaux-arts in Montreal. However, the relationship between the modern artist and the school’s conservative director, Charles Maillard (1887–1973), was doomed from the start. Rather than imposing a concrete aesthetic, Pellan encouraged his students to go beyond what was taught and find their own way: “When I taught,” he said, “I sharpened the awareness of my students, I sowed uneasiness, I stimulated research: and the students learned to observe, to question themselves, to make their own discoveries.” In 1945, Maillard forced two of Pellan’s students to withdraw their paintings from the École’s annual exhibition, claiming the work was morally questionable. The subsequent events led to the director’s resignation and cemented Pellan’s status as an anti-academic artist who defended freedom of expression.

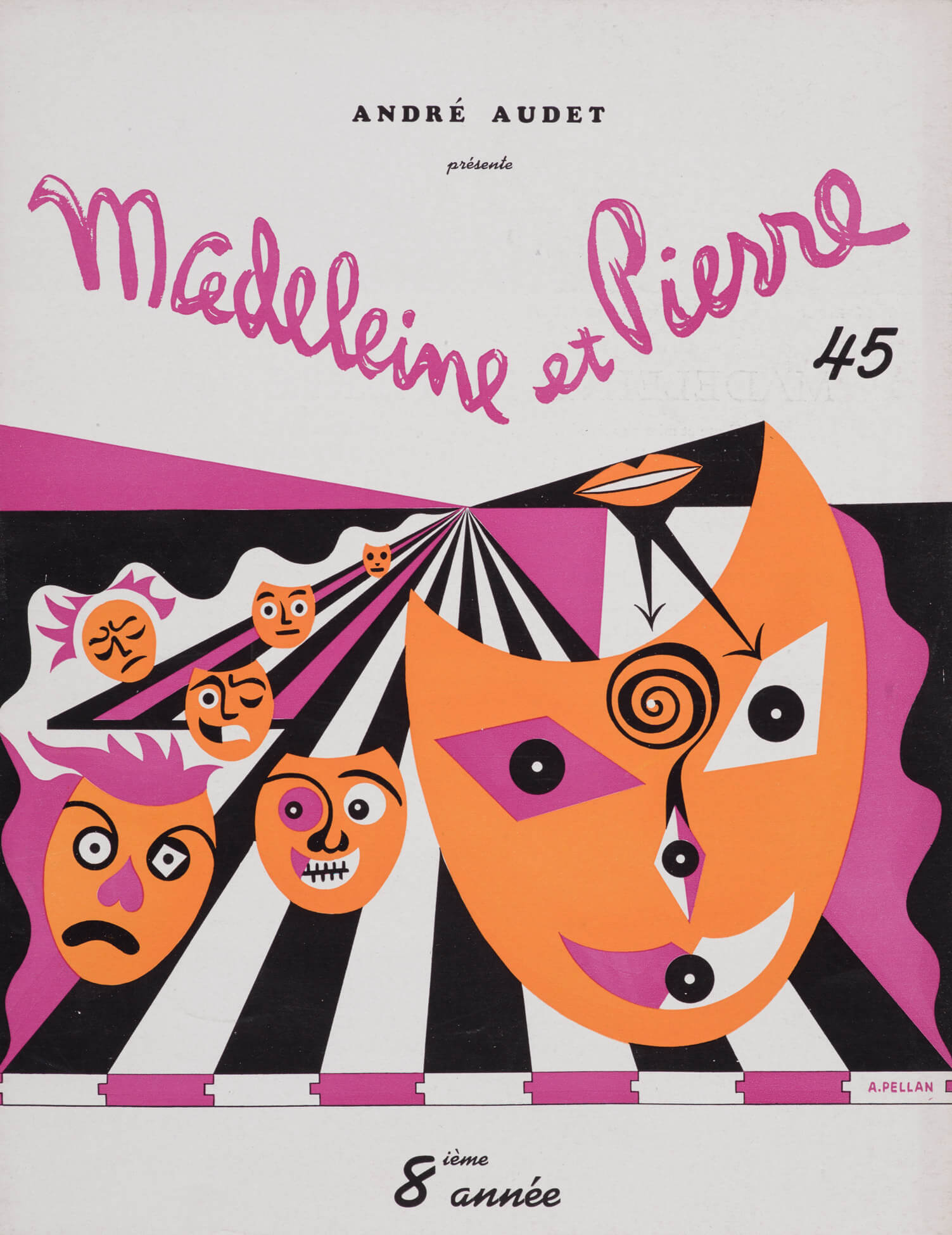

During this period, Pellan further expanded his technical repertoire. In winter 1945, he created “unforgettable” costumes and set designs for the theatrical production Madeleine et Pierre (Madeleine and Pierre), inventing “a world where harmony of forms and colour evoked real space.” The following year Pellan outdid himself, creating one of the “grandest gestures” in Canadian art by designing the costumes and sets for Les Compagnons de Saint-Laurent’s production of Shakespeare’s Le soir des rois (Twelfth Night).

Until the late 1940s, avant-garde artists in Montreal had presented a relatively united public front. But by the end of the decade, tension developed between Pellan and radical painter Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), and the Contemporary Arts Society “became divided into two factions, each of which sought to prevail.” The conflict specifically involved Les Automatistes, a group led by Borduas, and members of Prisme d’Yeux, which was founded by Pellan in 1948. Borduas believed that Pellan’s presence within the modernist camp endangered the unity of the Contemporary Arts Society and hence its collective strength, while Pellan contended that Borduas threatened the independent spirit of the CAS. When Borduas was voted president in February 1948, Pellan resigned.

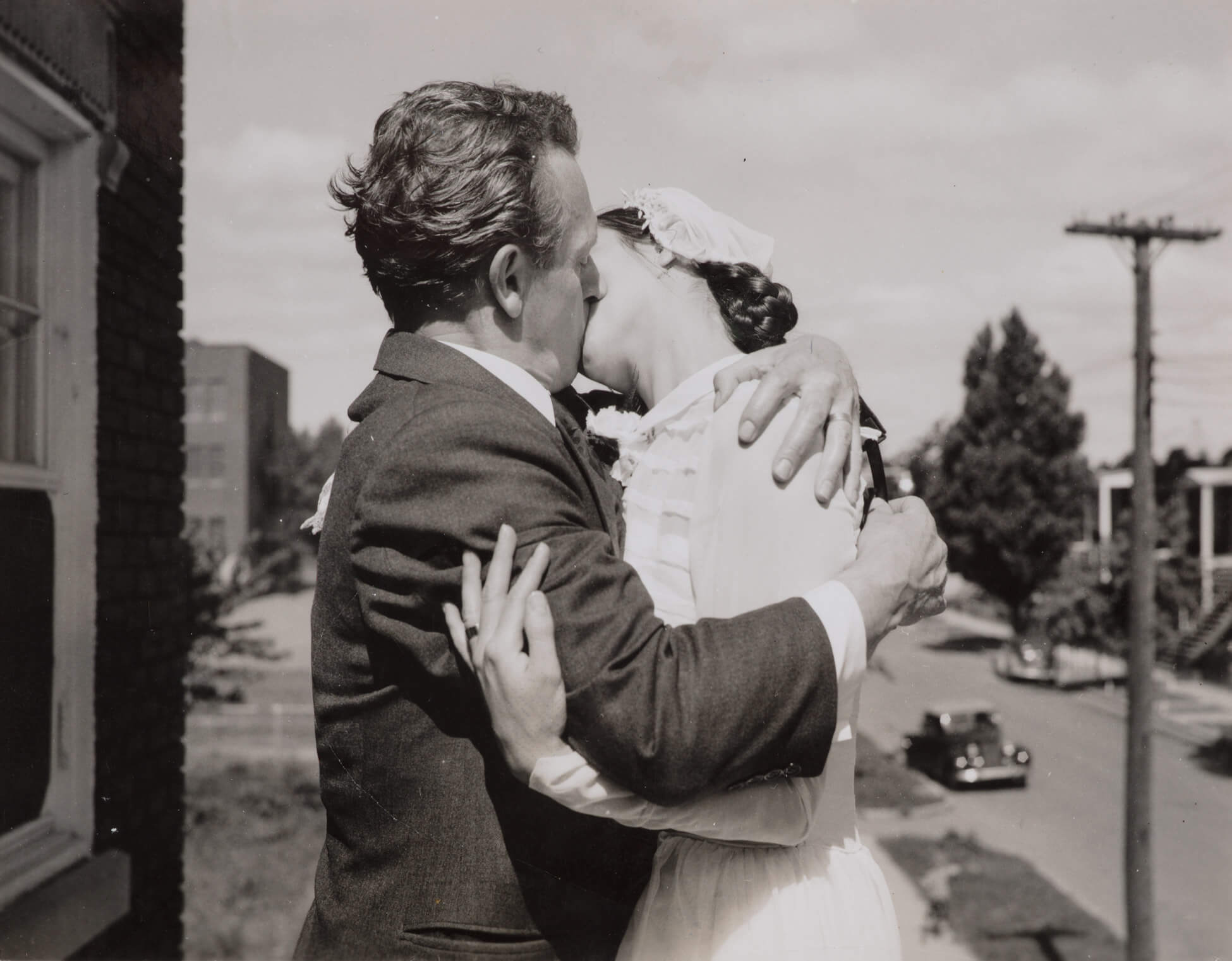

Although he had parted ways with that particular group, Pellan nevertheless maintained his standing in the Montreal art scene, collaborating with others and attending many parties and events. It was at one such party at the home of artist Jacques de Tonnancour (1917–2005) that Pellan met Madeleine Poliseno, whom he would marry on July 23, 1949.

Courting Controversy

Pellan’s work received wide acclaim throughout the early 1950s. In 1952, he was selected—along with Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974), Emily Carr (1871–1945), and David Milne (1882–1953)—to represent Canada at the Venice Biennale, where he exhibited several paintings, including Surprise académique (Academic Surprise), c.1943, and Les îles de la nuit (The Islands of the Night), c.1945. That year Pellan also received a scholarship from the Royal Society of Canada, which allowed him to spend twelve months in Paris, where he planned to study techniques for murals, illustration, and theatre design while also participating in group and solo exhibitions.

In 1955, Pellan became the first Canadian to have a solo show at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, France’s modern art museum. Curator Jean Cassou (1897–1986) assembled eighty-one paintings, drawings, costume sketches, and tapestries that he felt represented an oeuvre “animated by secret reason, tumultuous with mysterious drama and interior myth.” These themes are evident in paintings like La chouette (The Owl), 1954 (acquired by the Musée National d’Art Moderne in 1955), which blends a certain Surrealist mystique with intense sensuality, a combination that is equal parts disturbing and fascinating.

Pellan grew disappointed by Paris during his year in the French capital. He disliked the rivalries between the city’s young artists, who vied with one another to capture the attention of the galleries and the press. “We helped each other during the time I was there. That’s quite finished,” he observed. And after he returned to Canada in 1955, Pellan was no longer welcome at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal, as evidenced in a letter by director Roland-Hérard Charlebois (1906–1965). He was also denied an exhibition by the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal. This continued resistance to Pellan’s body of work may not have been a sign of the artist not being “à la mode,” as he put it in an interview around that time. Instead, it may reflect the fact that institutions were loath to take overt risks with art that could not be easily classified, and were consequently wary of Pellan, whose oeuvre did not seamlessly fit into pre-existing categories.

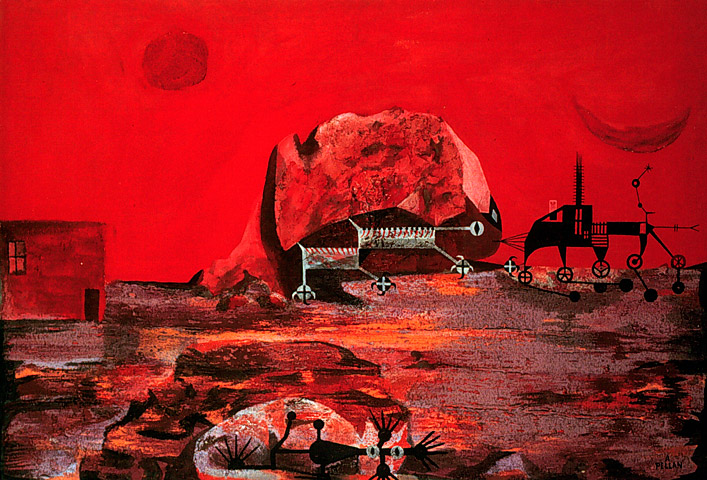

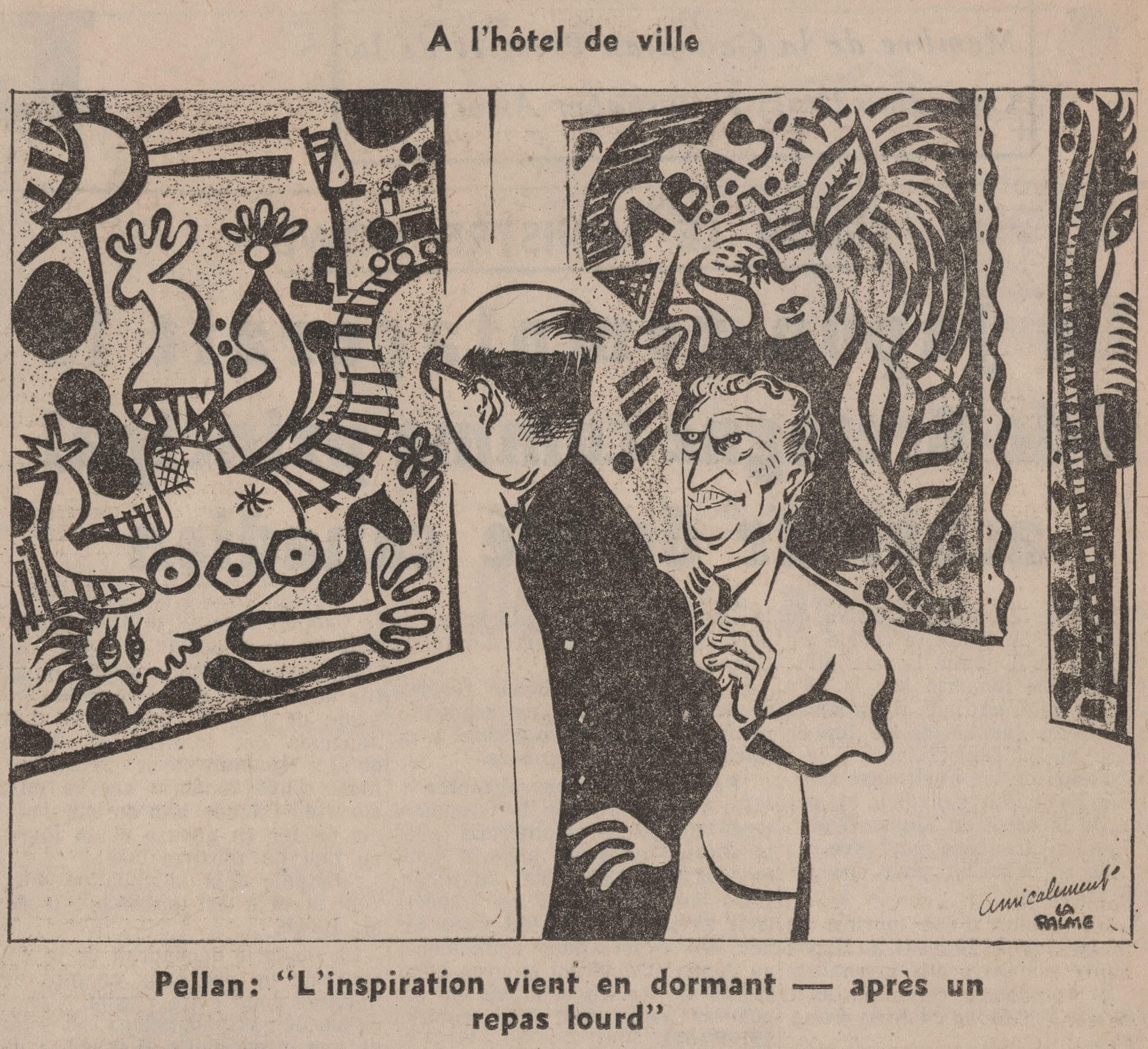

In spite of these setbacks, Pellan’s works were not lost to obscurity. In 1956, with the help of Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau (1916–1999) and secretary of the province Yves Prévost (1908–1997), he was able to exhibit more than one hundred works at City Hall. There he displayed new techniques—influenced by artists he had met in Paris, such as André Breton and Max Ernst—that seemed inflected with what critic Charles Doyon described as “an allegoric surrealism,” an unusual approach that is seen in L’affût (The Stalker), 1956, and Le front à catastrophe (The Disaster Front), 1956. The exhibition affirmed Pellan’s position in Canadian art history, as it exemplified the painter’s ongoing commitment to exploring diverse forms of expression and upholding artistic freedom.

After the exhibition opened, city councillor Antoine Tremblay declared himself “disgusted” by the artist’s work, calling out paintings like Sur la plage (On the Beach), 1945, and Quatre femmes (Four Women), 1944–47, in particular. He maintained that the individuals who worked at City Hall would feel embarrassed by the “obscene” and “immoral” nature of Pellan’s art.

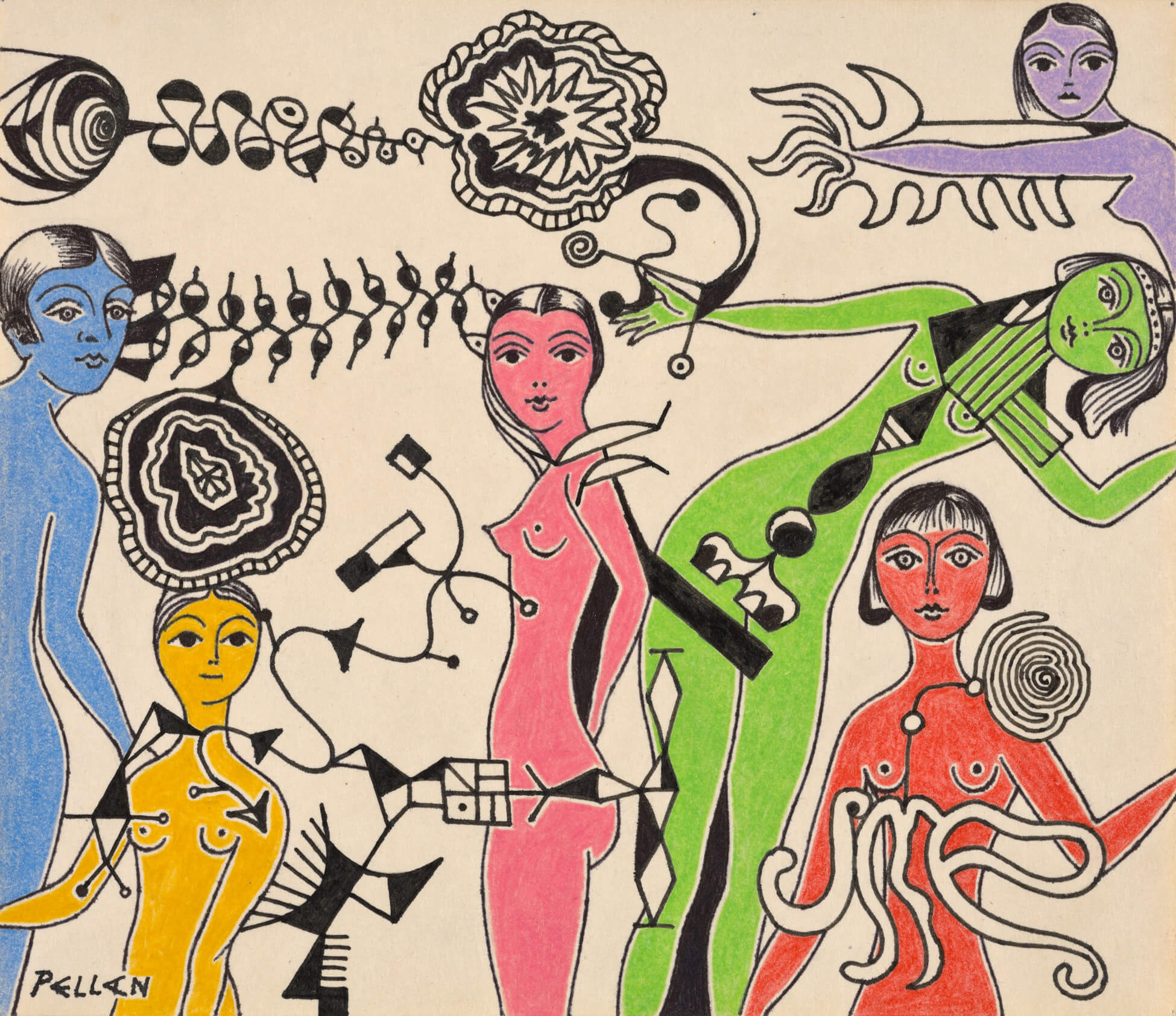

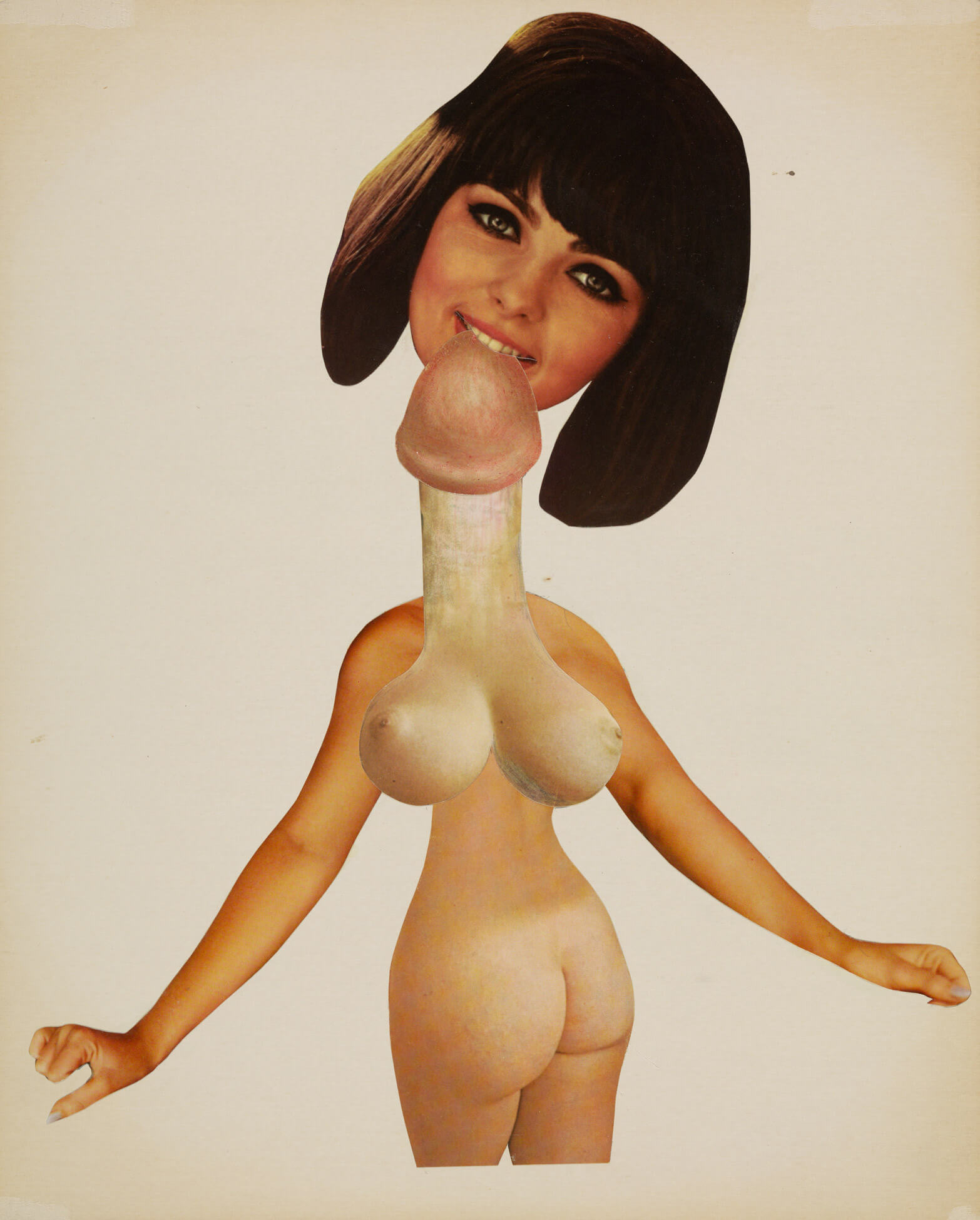

Although Pellan had the full support of the press—some mocked Tremblay for his old-fashioned attitude, others for his ability to see obscenities in “semi-abstract canvases”—he was compelled to withdraw three of his works. Two of these paintings were allegedly offensive because they depicted women in “provocative positions.” To be sure, Pellan’s art was dominated by the nude female form presented in sensual poses—not simply as an object of desire, but as a visual representation of (carnal) pleasure. In a 1960s interview, the artist suggested that many forms of art portray sex as something sacred and insisted that modern art “has the means to reach the same level.” The sexuality in his paintings, drawings, and prints echoed his defiance of societal norms in an environment that was still largely dominated by the mores of the Catholic Church.

That influence was apparent when Pellan was told to remove the third painting because it could be interpreted as a “modernist antithesis to a biblical scene.” Pellan was amused, as he was typically accused of creating “incomprehensible things.” He explained the purpose of the three censored paintings and declared that the only concession he would make was to turn the canvases to face the wall and that he would clearly identify his censors. It was an act of malicious compliance: Pellan did what he was told, but his approach provoked even more public attention and discussion.

There was one place where Pellan could create at will without fear that his ideas would be suppressed or sanitized. In 1950, he and his wife, Madeleine, moved to an old house in Sainte-Rose, about an hour’s drive from Montreal, which he renovated and turned into a studio. The building served as a three-dimensional embodiment of Pellan’s oeuvre: its walls were decorated with fantastical creatures, and the inside was painted in vibrant colours. Although the artist created this idyll away from the city, he maintained that he didn’t live a hermit life: “I go to see certain exhibitions in Montreal,” he explained in 1970. “Especially those of the young ones.”

In 1958, a year after he had started teaching at the Centre d’Art de Ste-Adèle, Pellan received a grant from the Canada Council that allowed him to produce his Jardins series of pictures, including Jardin rouge (Red Garden), 1958, and Jardin vert (Green Garden), 1958. In a climate where an oeuvre could centre on production techniques, he abandoned his strict lines and complicated compositions in order to experiment with plasticity, or three-dimensionality, in his paintings. This series illustrates Pellan’s ability to tackle current trends in contemporary art.

A Man in the Sixties

In the late 1950s, a time when many Quebec residents traded rural, agrarian practices for a more urban, industrial lifestyle, there was a belief among artists that painters and sculptors should intervene in public spaces in cities as a way to improve the quality of life. Murals exemplified art production during this period. Pellan, who as a young artist had been interested in combining painting and architecture, found there was renewed interest in his talent. In 1960, he created a mural for the Imaculée-Conception secondary school in Granby, Quebec. Two years later, he oversaw the construction of three compositions for private residences in the Montreal area.

-

Alfred Pellan, The Prairies, 1963

Oil on canvas, 6 x 32 feet

Installed at the Winnipeg International AirportThe work now hangs in the Montréal-Trudeau International Airport.

-

Alfred Pellan, Cosmos musical (Musical Cosmos), 1963

Stained glass, 152 x 1524 cm

Archives de la Société de la Place des Arts de Montréal -

Alfred Pellan, Stained glass window from the Église Saint-Théophile, 1964

Fonds Antoine Desilets, BAnQ Vieux-Montréal

-

Alfred Pellan, Reine des cieux ou Immaculée-conception (Queen of Heaven or Immaculate Conception), 1960

Ceramic mosaic, 200 x 340 cm

Cégep de Granby

In 1963, he made The Prairies, a “lively composition of abstract shapes and colours,” for the Winnipeg Airport. That same year, he created a glass mural for the bar in the new concert hall of Place des Arts in Montreal. He used a new technique that allowed him to eliminate the customary iron framework: separate pieces were fused together, creating one large pane of glass. The effect was astounding: reviewers highlighted the subtle fluctuations of light that cut through the glass as if through a prism.

Pellan used the same method for the panels of the Église Saint-Théophile in Laval-Ouest in 1964. He also created a stained-glass piece for the École Sainte-Rose and, in 1966, a mural for the national library in Ottawa. These creations were easily accessible by virtue of being in public spaces and helped shape the urban landscape of these cities.

During the 1960s, Pellan became a central figure in a wider movement to establish Quebec artists as Old Masters and mentors to a new generation of creators. He had received the national award in painting and related arts from the University of Alberta in 1959. The following year, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa organized a retrospective of his work: “In choosing to honour Pellan’s achievement, the three sponsoring galleries [the National Gallery, the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, and the Art Gallery of Toronto] hoped to realize a clearer picture of his evolution and to provide an opportunity to assess the nature and the extent of his influence upon contemporary Canadian painting,” explained Evan Turner (1927–2020), then director of the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal.

As the decade progressed, Pellan emerged as a key innovator in the province’s visual arts community. In 1963, Guy Robert (1933–2000) published an extensive study of the artist’s life and work—the first comprehensive volume of this nature since Maurice Gagnon’s book in 1948. Two years later, Pellan received a medal from the Canada Council for the Arts. The council had been created in 1957 in the wake of a 1951 report by the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences, commonly known as the Massey Commission. That assessment described a bleak cultural landscape in which gifted Canadians “must be content with a precarious and unrewarding life in Canada, or go abroad where their talents are in demand.” Pellan, who had achieved success abroad and in his home country, was celebrated because he fostered the production of art and promoted its study and enjoyment.

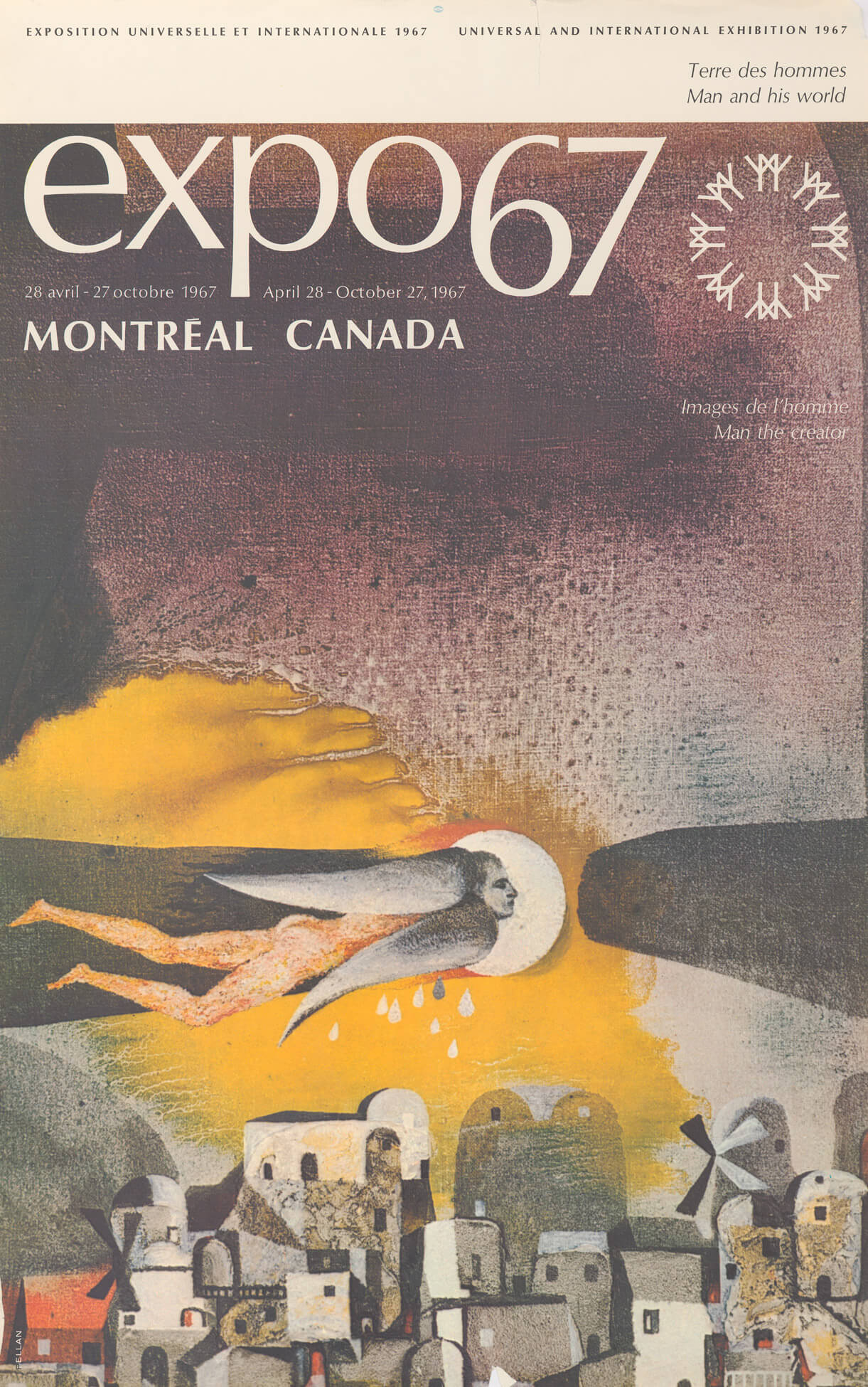

In the lead-up to Expo 67, Pellan’s work Icare (Icarus), 1956, was chosen to adorn one of the promotional posters for the event, which marked the one-hundredth anniversary of the Canadian Confederation in an international arena. As well, the artist, who was said to possess “greater imagination and inventiveness than most of his fellows,” received a Canadian Centennial Medal—a commemorative award given to individuals who had demonstrated outstanding contributions to public service.

That same year—1967—Pellan was made an inaugural member of the Order of Canada—a symbolic honour established by Queen Elizabeth to celebrate Canadians who have made a significant mark through both service and exceptional accomplishments. In 1969, the year he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Ottawa, Pellan had a solo exhibition at Montreal’s Musée d’art contemporain, where poet Louis Portugais (1932–1982) screened Voir Pellan, 1969, a unique mosaic-like film project that allowed people to “really see” the artist’s oeuvre.

In spite of all these accolades, Pellan continued to experience tension with those who disagreed with his views and did not understand his work. He resigned two months into his tenure as a consultant for the Conseil provincial des arts, where he was hired in 1962 and tasked with recommending scholarships for artists, musicians, and writers. A “senior official of the government very close to the issue” declared that Pellan’s “figurative tendencies could not be reconciled with those non-figurative [views] of certain other members of the Art Council and, for this reason, he preferred to withdraw than to sit with those that didn’t share his pictorial ideas.” The conflict seemed to revolve around a wider discussion about whether abstract art was a worthwhile category. In an effort to reframe the conflict, Pellan stated, “I regret that the controversy has been reduced to an incompatibility of the pictorial concept that is supposed to exist between my ex-colleagues and me.… And why the desire to class me in the category of figurative painters?”

Later Life and Legacy

By the mid-1970s, the establishment had come to embrace artists and art forms that had typically been associated with the Quebec avant-garde. Exhibitions were organized, documentaries were sponsored, and awards were bestowed. There was renewed appreciation for Pellan’s achievements in the visual arts—and recognition followed accordingly: in 1971, he was granted honorary doctorates by the Université Laval and Sir Georges Williams University, became a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and assumed the role of honorary president of the Guilde graphique de Montréal. In 1972, he received the Louis-Philippe-Hébert Prize from the Société Saint-Jean Baptiste, awarded to great Quebec painters.

A huge retrospective of Pellan’s art was mounted that year by the Musée des beaux-arts de Montreal and the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, featuring for the first time a selection of his Mini-bestiaires (Mini-Bestiaries), 1971–75, an important evolution in his experiments with Surrealism. The exhibition, which covered his career from the 1930s all the way to his most recent work, focused mainly on paintings to give “pride of place” to the artist’s “completed thoughts.” It explored thematic continuities (such as his insistence on colour as the defining element in his painting) and outliers (such as the Jardins (Garden) series from 1958, in which he abandoned his complex drawings). The show demonstrated that Pellan’s work had achieved a level of sophistication that “was so complex and of technical accomplishment and personality as to discourage imitation.”

In 1973, Germain Lefebvre published the second biography of Pellan, who was also the recipient of the Canada Council’s Molson Prize, an award that aimed to “recognize and encourage the exceptional contributions to the arts, the humanities and the social sciences.” The following year, Pellan received an honorary doctorate from the Université de Montréal, and in 1978, the Hotel Reine-Elisabeth in Montreal honoured the artist as one of twenty people whose contributions “make Montreal an extraordinary city.” As a Montreal Gazette article suggested, the choice was a “most understandable and laudable one.” The Quebec establishment was sending Pellan a clear message: “You have arrived. You are accepted. You are one of the greats.”

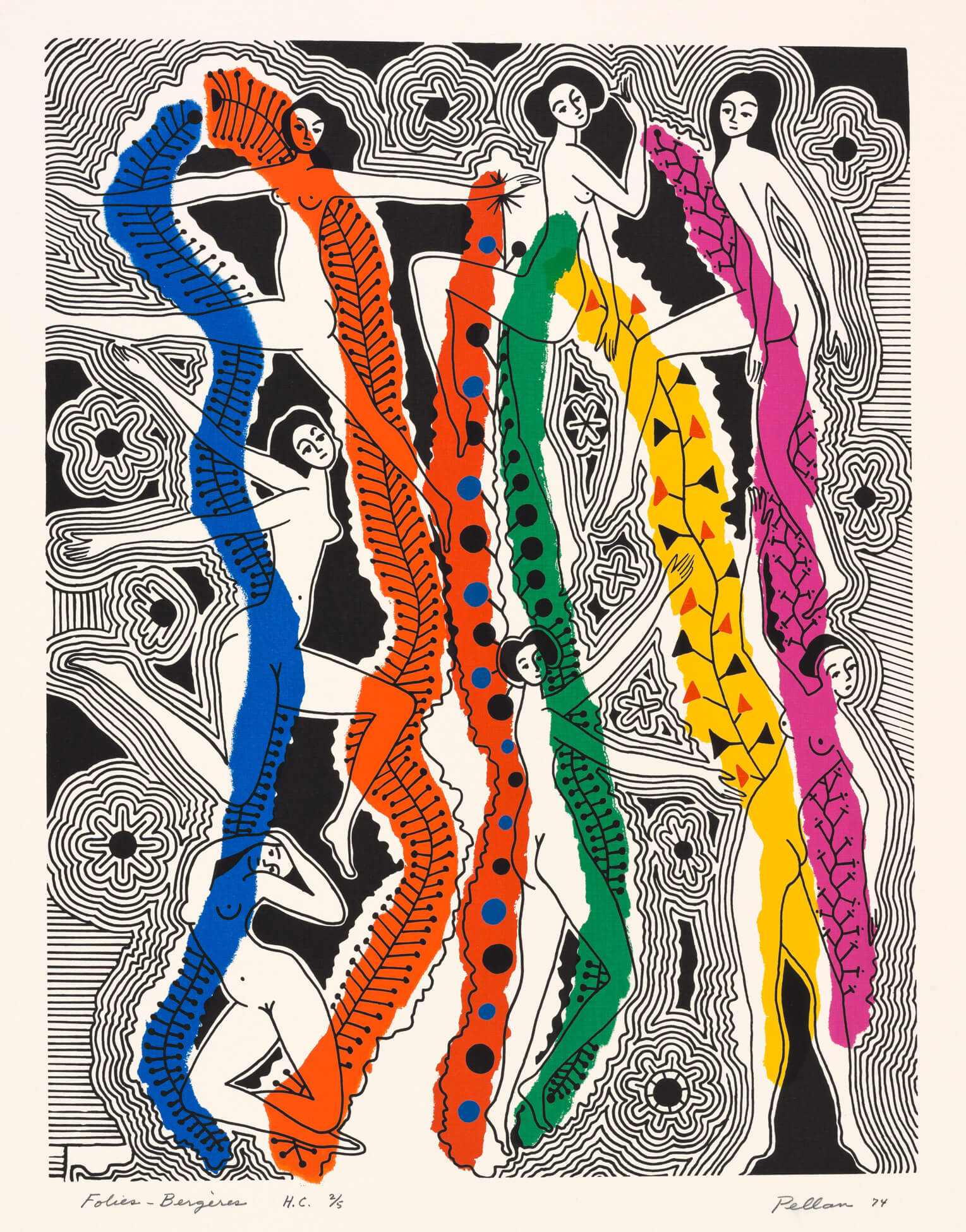

In the meantime, Pellan continued to work. Between 1968 and 1980, the artist created an impressive graphic oeuvre, which was largely made up of serigraphs, a form of silkscreen printing. These works were often reinterpretations of his earlier paintings, as, for instance, with Baroquerie (Baroquerie), 1970, which was published as a serigraph in 1975. They were never mere copies, however: while reproducing some elements, he distorted others and experimented with new variations. He “simplifie[d] and reorganize[d] his forms and colours, he transform[ed] the proportions of support”—in short, he recreated his world.

Perhaps most importantly, in 1984 Pellan received the Paul-Émile Borduas Prize “for his dynamic contribution to art education, for his struggle for the indispensable freedom of artistic expression and for his works, known and recognized in Québec as well as abroad.” When asked about the irony of the honour, given his notoriously acrimonious relationship with Borduas, Pellan said that the award served as a sort of compensation for everything he had endured. His wife, Madeleine, saw it as proof of at least one thing both artists had in common: “passion for their art.”

After suffering for years from pernicious anemia and rheumatism, Pellan died on October 31, 1988. One of the province’s greatest artists, he was a “giant of Quebec modern painting,” who refused to be identified with a specific school. His place in Canadian art was rather that of “prophet and creator.” As a pioneer of modernism, Pellan was a key figure in a movement that “initiated a break with traditional social and intellectual customs, encouraged broader and freer educational opportunities, and enlarged horizons of thought” in French Canada. His Parisian-inspired oeuvre delivered a vigorous blow to the cultural lethargy that prevailed in Quebec in the mid-twentieth century.

For Pellan, the prospect of creating a truly free visual language, uninhibited by ideology, school, or even media, was a lifelong quest: he created astounding work that encompassed academic drawings, paintings inspired by Surrealism and Cubism, large-scale glass murals, intensely colourful graphics, strange and curious objects, and poetic experiments in theatre design. With Pellan’s death, Canada lost a “sorcerer” who yearned to expose poetry in life through his art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements