The 1970s was a period of experimentation for Quebecois artist Françoise Sullivan (b.1923), as for many artists of her generation. One of the preoccupations they shared was an interest in the commodification of art and what they considered to be its senseless accumulation in institutions. As Sullivan explained in 1973, “I have in my heart a great love for art, but I am uncomfortable when I say that word. The artist devotes his life to doing a job that is becoming impossible. Our world is saturated with art objects. What should he do then?” It seemed that the art world was falling apart.

Photograph by Alex Neumann

Sullivan defined conceptual art as a “mental approach on the part of the artist.” For her, “the means and materials by which [artists] concretize this approach [are] of secondary importance. This attitude gives priority to attitude over achievement.” This experimental approach gave her the latitude to freely explore photography, photomontage, writing, and performance art. At Galerie III in Montreal in 1973 she showed personal mementoes and notebooks from a recent trip to Italy, as well as her bodily fluids, in an exhibition simply titled Françoise Sullivan.

Photograph by David Moore, archive of the artist

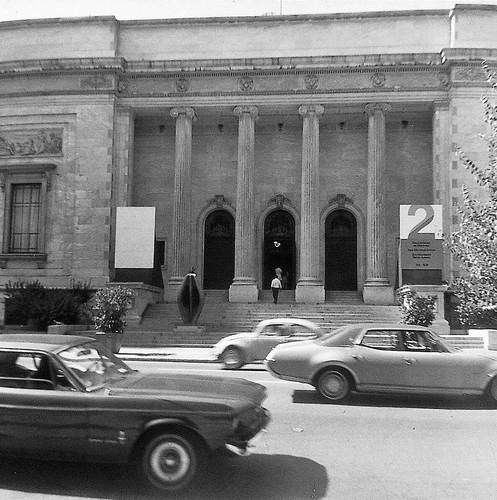

Some of Sullivan’s best-known works from the period are performances. They belong to what Allan Kaprow (1927–2006), a pioneer in establishing the concepts of performance art, had described in the early 1960s as Happenings. These were art events that did not fit in the established traditions of visual arts, theatre, or dance but nevertheless allowed artists to experiment with body motion, sounds, the environment, and written and spoken texts while interacting with other performers or the public. Sullivan’s first performances consisted of loosely scripted walks that were documented photographically. In 1970 she walked from the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal to the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal. As she strolled she took pictures of what she saw. In 1973 she had herself photographed as she explored an industrial park populated with oil refineries in Montreal’s east end. In 1976 she created a guided walk for the public through Montreal’s cultural past, involving exhibition cases and panels she had placed on the sidewalks. And in 1979 she produced Choreography for Five Dancers and Five Automobiles, a piece to be walked and danced, during which five performers and five automobiles intermingled in Old Montreal.

Thirty-two gelatin silver prints and a map, each photograph and the map: 26.6 x 26.6 cm, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

In other instances, she explored repetition, and the construction and deconstruction of open and closed spaces. Around 1971, inspired by a dream of being shut out of her own home, Sullivan began to photograph doors and windows in condemned buildings. While in Italy and Greece, she created photomontages of suburban houses and phone booths filled with large stones. During a trip to Ireland, Sullivan embarked on a series of intensely physical performances in which she painstakingly moved stones of different sizes to block and unblock doors and windows (Blocked and Unblocked Window [Fenêtre bloquée et débloquée], 1978). This was a reference to a social history in Ireland, when British lords applied a housing tax on a home’s number of apertures and the Irish resisted by blocking their windows and doors.

Tar, acrylic, photo, and collage on canvas, 112 x 84 cm, collection of the artist

In 1979, in a Happening titled Accumulation that took place at the Ferrare museum in Italy, she cleared a doorway by removing the stones that blocked it, arranging them into a large circle in an open space. Meanwhile, inside the museum, a young woman was dancing Daedalus (Dédale), Sullivan’s choreography from 1948. She also made works that integrated the ruins of Delphi, Greece, using them as a material more than as a backdrop: for example, in Shadow (Ombre), 1979, she had herself photographed by David Moore (b.1943) as she walked through them, creating shadows with her body on the wide expanses of stones.

Instruction of Paul-André Fortier performed by Françoise Sullivan during the opening of the exhibition do it Montreal, Galerie de l’UQAM, January 12, 2016, Montreal. Photograph by David Ospina.

The same ideas recur in many of these works in a variety of mediums. Sullivan highlights the poetry of everyday life, blurring the lines between art, life, and dream, exploring contemporary ways to understand archetypes and myth. The medium becomes secondary; for Sullivan “[w]hat really counted was the idea.”

This Essay is excerpted from Françoise Sullivan: Life & Work by Annie Gérin.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix