Indigenous leaders, Chinese and European settlers, cowboys, miners, families, friends, men, women, and children: the extraordinary work of C.D. (Chow Dong) Hoy is a unique window into the diverse community of Quesnel, British Columbia, in the early 1900s. One of the earliest Chinese Canadian photographers, Hoy lived and worked in the Cariboo region of B.C. from 1905 until his death in 1973. His images challenge us to reflect on how we understand the past, and how we celebrate identity and community.

The Photographer in Quesnel

Born in Guangdong Province, China in 1883, like many of his countrymen Hoy was compelled by poverty and socio-political unrest to emigrate to Canada. He landed in Vancouver at the age of nineteen. Indebted to his family in China who had paid for his passage, Hoy worked his way north through a series of jobs with steadily increasing pay that included dishwashing, cooking, and surveying. For instance, for two years he worked as a cook for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort St. James. While there, he learned to speak the language of the local Indigenous trappers, left his job, and opened Hoy’s Trading Post―not two miles north of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

This type of adventurous risk-taking eventually propelled him to the gold mining town of Barkerville in the spring of 1909 where he picked up a camera for the very first time. It is not known how he got this camera, how he learned to operate it, or where his portrait studio might have been: one day he was an underemployed gold miner and the next he was a photographer. However, there is no doubt that Hoy took up photography because he saw an economic opportunity. According to his own memoir, his first clients were miners whose portraits he glued onto postcard stock paper so that they could be mailed to family and loved ones left behind.

In the early winter of 1909 Hoy returned to Quesnel, a town known to him through his previous employment there as a hotel dishwasher. He held a series of jobs in and around Quesnel prior to purchasing a dry-goods business on Barlow Avenue from a merchant who had wanted to return to China. Hoy embraced this opportunity and the town, becoming a well-respected community member, a father of twelve, and for many, the man you visited to get your photograph taken.

P1687 Barkerville Historic Town Archives.

The history of Quesnel is shaped by the gold rushes that followed the 1857 Fraser River excitements up and into the Cariboo region. The confluence of the Fraser and Quesnel rivers, the place where the town was ultimately established, saw mining activity as early as 1859. Most people passed through on their hopeful way towards the richer diggings that were found in and around the creeks upon which towns like Barkerville were built. Quesnel quieted into a provisioning town supported by farmers, ranchers, freighters, and merchants. The population at this time was approximately six hundred people, with the majority being Caucasian settlers from places in Eastern Canada, the United States, and Europe. The town also had a sizeable Chinese population drawn into the area by opportunities related to gold mining.

The original inhabitants of this area are the Lhtako people of the Dene-speaking Dakelh Nation. The Lhtako moved through this expansive territory by water and land on their seasonal rounds―hunting, fishing, gathering berries and medicine, and visiting and trading with other Indigenous groups and Nations in the broader region. With the incursion of the settler population in the 1860s, this local Indigenous population was decimated by smallpox. The same was true elsewhere in the region.

P1716 Barkerville Historic Town Archives.

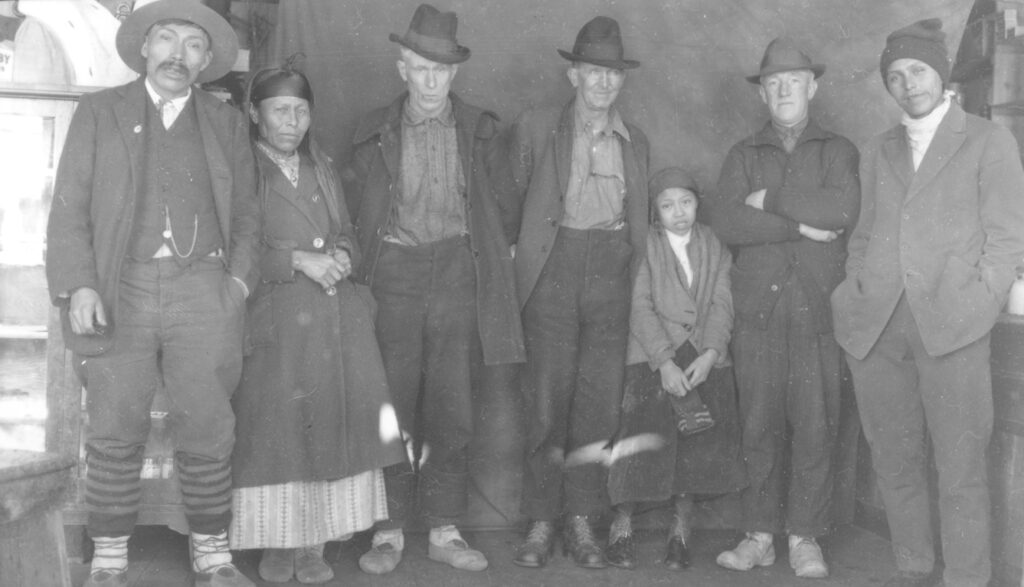

While the occasion of this photograph is unknown, it illustrates connections between Caucasian settlers and Indigenous people in the community. The smaller person is quite possibly Louise (Louisa) Yargeau née Boucher, while the older Indigenous woman is quite possibly her mother Lizette Allard.

Starting in 1876, the people who had survived were pushed onto reserves that had been established by the Indian Reserve Commission. The Dakelh people lived on or near reserves at Nazko, Kluskus, Ulkatcho, and Quesnel. The Tsilhqot’in, who lived further south and west, also had their lives fundamentally restructured from the semi-nomadism of the seasonal round to ranching. These families either worked for themselves from their reserves at Anaham, Redstone, Toosey, Stone, Alexis Creek, Alexandria, and Nemiah Valley or found employment working for new ranching families that moved into the area and pre-empted the suddenly available rangelands.

The Photographs and Their Significance

Hoy took approximately 1,500 portraits of people who lived in and around Quesnel and Barkerville c.1909 to 1920. The people who sat before his camera were either townsfolk, local farmers and ranchers, or transient miners on their way through Quesnel, and they include individuals, families, lovers, and friends. The images were taken in indoor studio settings, a series of makeshift outdoor studio settings, and at peoples’ homes, farms, and ranches. Some people dressed for the occasion, some came as they were.

Importantly, the collection is divided almost exactly in thirds in relation to the representation of Indigenous, Chinese, and Caucasian people, indicating not only the then incredible diversity of frontier regions like the Cariboo, but also that each of these cultural groups felt equally comfortable beneath the levelling gaze of this Chinese man and his camera. Then again, perhaps not. He was, after all, the only town photographer until a second photographer showed up in 1918: remarkably, a man who was also Chinese.

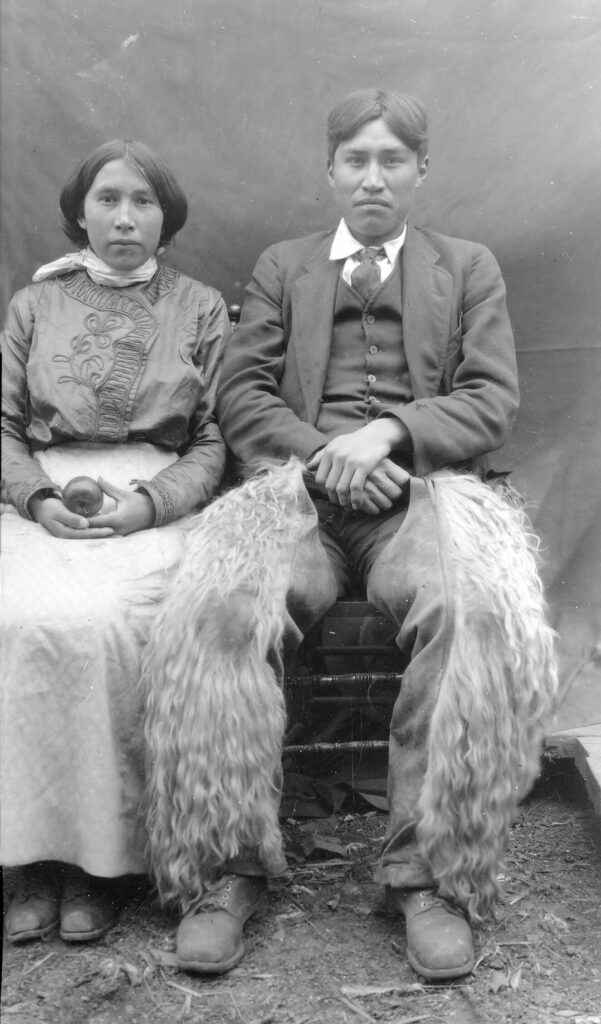

P1583 Barkerville Historic Town Archives.

This powerful portrait of Tsilhqotʼin Chief William Charleyboy and his wife Elaine from Redstone is one of the most striking of Hoy’s images.

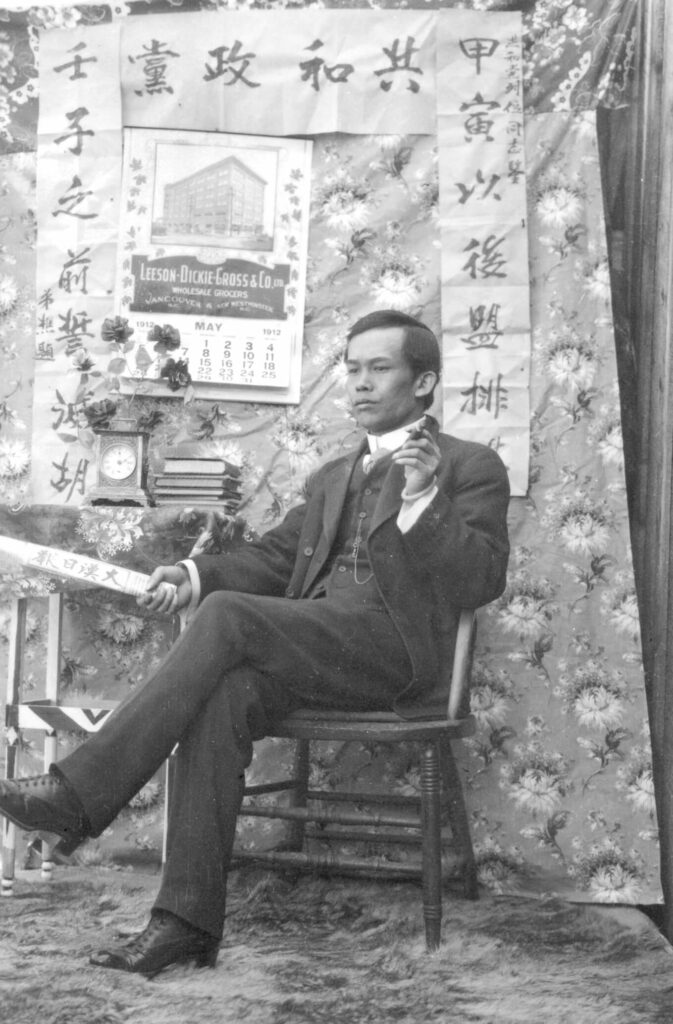

Although Hoy left no narrative behind as to how he acquired his skills, there is ample evidence that he was influenced by conventions of Chinese ancestor portraiture and early Hong Kong photographic portraiture. Many of the Chinese sitters in Hoy’s photographs have either consciously chosen or been posed in manners that mirror the tropes of Chinese ancestor paintings. Typically, these include frontality of the body with widely triangulated legs gripped by broadly splayed fingers. When photography was first introduced into China through Hong Kong, these same postures began to be recorded with cameras. The imported European studio backdrops shifted to include small, elegant tables upon which were displayed items that were connotative of the Chinese scholarly class―books, pipes, teacups, and clocks. The poignancy of these motifs appearing in Hoy’s images is heightened by the fact that immigrants from China at that time were not from the scholarly class, the evidence of which is seen so easily in the pronounced placement of hands that, upon close inspection, attest to so much hard labour.

Another important element in Chinese photographic portraiture is the depiction of highly symbolic plants and flowers. Many of Hoy’s studio photographs include evergreen branches, which in Chinese art were often associated with longevity. His go-to cloth backdrop was festooned with chrysanthemums, a late-blooming flower that represented the overcoming of adversity. The symbolism of Hoy’s backdrops would not have been lost on his Chinese sitters, though it probably was on the Indigenous and Caucasian people who were also photographed in this decidedly Chinese studio setting. These particular images, then, become evidence of cultural transference in places where people of different ethnicities lived in proximity to each other.

The sitters themselves profoundly extend this theme. The Hoy photographs are replete with Indigenous women wearing Edwardian dresses with soft-toed moccasins peeking out from their voluminous skirts. Caucasian women are depicted wearing resplendent finely beaded gloves, with some Caucasian men, who appear to be hunters or trappers, also shown wearing the very practical Dakelh moccasins. Chinese men are mostly depicted wearing Western-styled business suits. Some of these men are Western right down to their shoes, while others prefer to hold onto traditional footwear.

P2023 Barkerville Historic Town Archives.

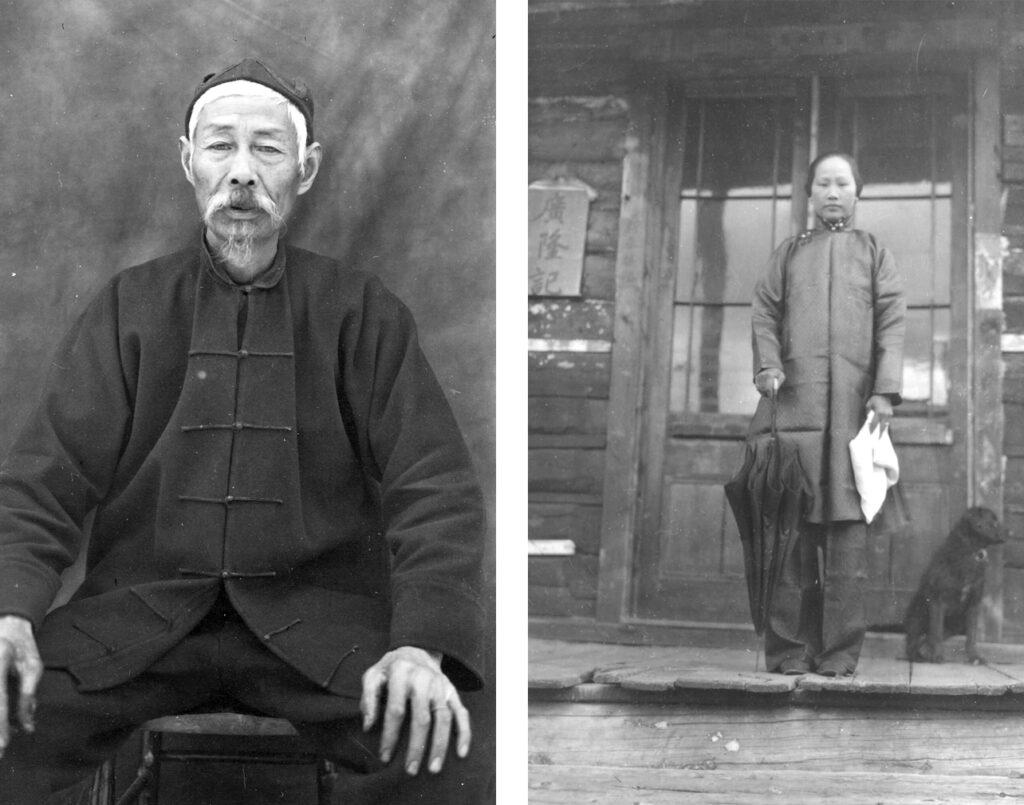

RIGHT: C.D. Hoy, Mrs. Won Gar Wong, 1912

P1978 Barkerville Historic Town Archives.

However, there are notable exceptions to this general trend in Hoy’s Chinese sitters. The portrait of a gentleman who is thought to be Lim Poi, a well-known pig farmer from the region, depicts no evidence of acculturation, although it is not known if these were his everyday clothes or if he chose to dress for the occasion. The same is true of the image of Mrs. Won Gar Wong, a merchant’s wife from the now ghost town of Stanley, photographed so beautifully on the porch of her store in her traditional Chinese clothing.

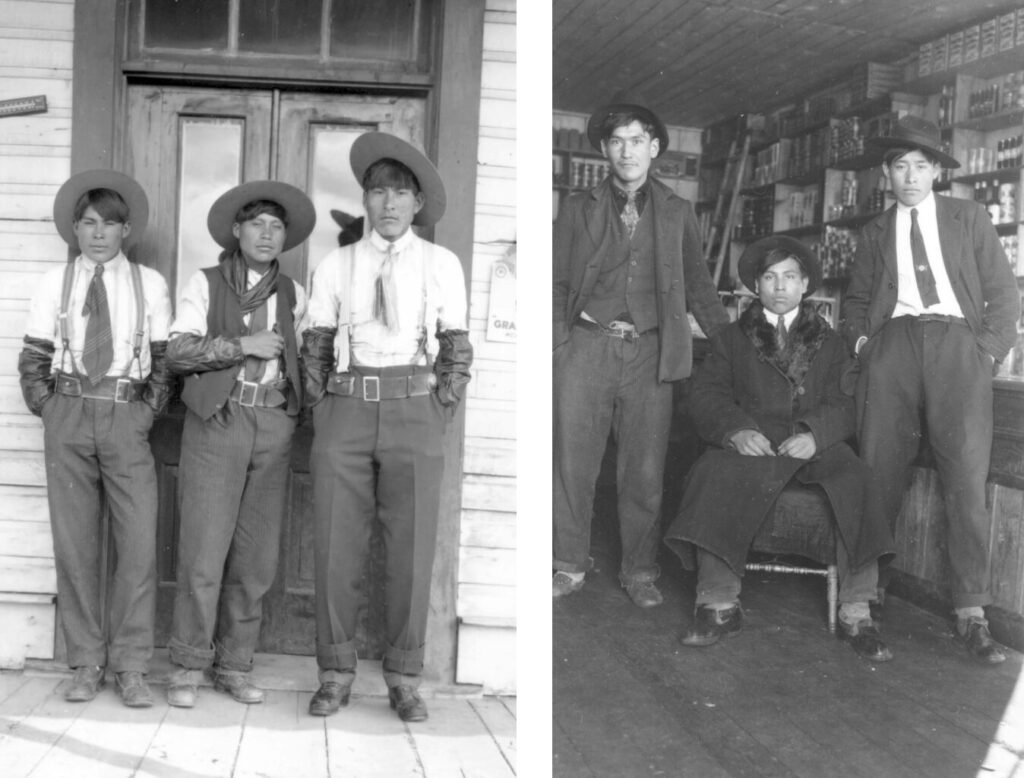

A series of images depict Indigenous men dressed to the nines. Close inspection of their clothing revealed that they were wearing two pairs of pants, with the outer pair rolled up to reveal the second pair beneath. The immediate assumption was that these clothes were provided by the photographer; it was not unheard of, after all, for studios to provide outfits for portrait sitters. Research revealed that these men were more than likely Tsilhqot’in horsemen who were in town for the annual rodeo that was held in Quesnel on Dominion Day. The long dusty trail to town on wagons necessitated the bringing of a good pair of pants for the rodeo and its attendant festivities. The Quesnel rodeo was one of many that took place in towns throughout the Interior of B.C. during the summer months, all of which were planned sequentially so that riders could appear and compete through the entire circuit. The traditional seasonal round related to food procurement and preservation had, to a significant degree, been supplanted in the move onto reserves by the economic and cultural activities of ranching: intensive requirements of spring and fall labour, and the summertime rodeo circuit, where winnings, if they could be had, were large.

P2025 Barkerville Historic Town Archives.

RIGHT: C.D. Hoy, Three unidentified Indigenous men in C.D. Hoy’s store, 1910–20

P1970 Barkerville Historic Town Archives.

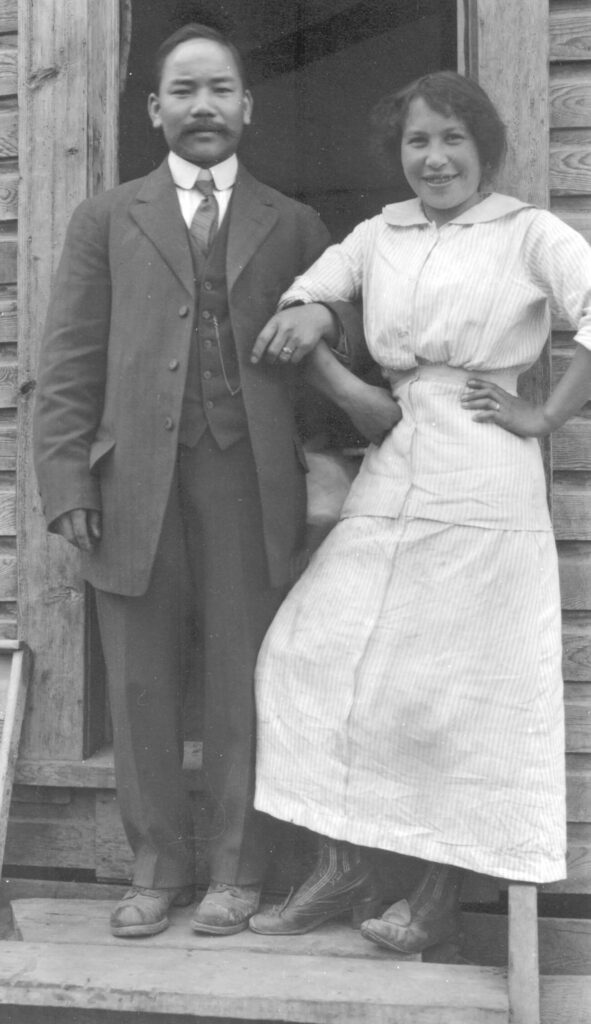

Hoy’s photographs are important documents of this forced transition from traditional livelihood to providing labour support for the nascent industries of ranching, farming, and mining. Somewhat consistent with this thematic of cultures in shift are the portraits of Chinese blacksmith, teamster, and cowboy Kong Shing Sing. Kong was the son of Chinese rancher Chew Nam Sing, one of the very first Asian men drawn to Cariboo by the lure of gold. Kong and his brother ran a freighting business between Barkerville and Quesnel along with running the ranch after their father passed away in 1910. Kong’s sister Yee (Laura) Sing is also featured in the Hoy images. Her confident pose and frank gaze into the camera suggest a certain comfort with both herself and her surroundings―not something to discount in view of the history of legislation against the very presence of Chinese people in Canada.

While the government actively worked to disenfranchise and exclude non-Caucasian immigrants and the Indigenous people of this land, a small-town photographer hailing from Southern China was creating a record that in many ways pushed back against these racist constructs. Perhaps that is nowhere better seen than in the many images of people who had created families and friendships across cultures, including the portrait that Hoy had taken of himself and the young Josephine Alexander, a Tsilhqot’in woman who worked for him. In the image, the ease and joy they take in each other’s existence is palpable. Her no-nonsense stance accompanied her as she sat for Hoy at least fifteen times―with her friends, her lovers, or husbands, and as she lovingly embraces someone who is quite possibly her mother.

P1972 Barkerville Historic Town Archives.

The real power in Hoy’s photographs lies in the very simple fact of their existence. When so much of what was happening at that time was about cultural marginalization and even erasure, the idea that these very people showed up at Hoy’s studio to celebrate their own existence is a powerful statement. That the well-heeled Caucasian townsfolk did not balk at the idea of being memorialized by the town’s Chinese photographer is also powerful. Hoy was there to capture it, offering all of us a glimpse into a small frontier town and the many people who, just by being photographed, shift our conceptions of what the past actually looked like. The hope of course is that there is a similar shift in our collective vision of the future.

For more works by C.D. Hoy and to see other photographs mentioned in this essay visit the online exhibition.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix