London, Ontario, artist Greg Curnoe (1936–1992) began his career during a decade of change and turmoil in Canada and the world. The sexual revolution, the Vietnam War, the increasing American influence on life in Canada, and Canadian nationalism shaped his thinking and his work. Curnoe was well versed in debates about American imperialism and Canadian national identity, which were waged in the media and in books by George Woodcock, Mel Watkins, George Grant, and Léandre Bergeron. Like other artists such as Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) and John Boyle (b. 1941), Curnoe exhibited his passion for Canada in his paintings, in journal articles, and in letters to the editors of newspapers. He believed that Canadian identity resided in regional cultures across the country, rather than in a single, unified sense of identity.

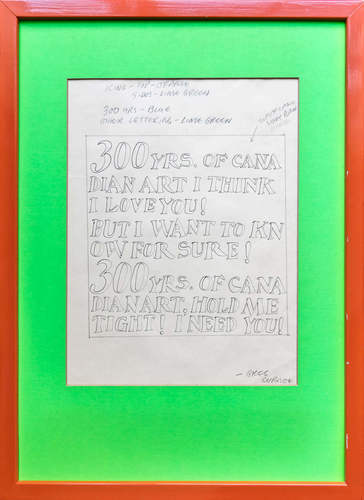

Design for Curnoe’s centennial cake with text based on “Wild Thing” by The Troggs, c.1967

Pencil on paper, collection of Stephen Smart

His ambivalent Canadian nationalism is exemplified in his design for Canada’s centennial cake, which was served at the opening of 300 Years of Canadian Art at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa in 1967. Curnoe’s works often gave visual voice, usually with humour, to what was happening politically in Canada, whether in his portraits of political leaders or in works that posed ironic questions.

For a time, much of this cultural nationalism was directed against the United States. In other words, the reverse side of his Canadian patriotism was “anti-Americanism.” He admitted to being anti-American, but it is important to understand that he was not against individual Americans or aspects of American culture, such as artists, poets, jazz, or comic books. Indeed, it was Curnoe who commissioned an exhibition by American artist Bruce Nauman (b. 1941) at London’s 20/20 Gallery in 1970. Rather, he was concerned with the “cultural imperialism” that he observed with the appointment of Americans in Canadian universities and cultural institutions, and with the corporate takeovers that were happening in London and across the country.

Greg Curnoe, For Ben Bella, 1964

Oil on plywood construction, plastic, metal, and mixed media, 159.6 x 125.7 x 98.4 cm, Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton

Further, on his first trip to New York City in 1965, Curnoe had been shocked by the violent mugging of a friend. He subsequently re-evaluated his feelings about the United States. Curnoe refused to exhibit his work there and, true to his principles, later turned down a lucrative opportunity to design a cover for Time magazine. Tellingly, he also excluded a reference to the Time review of the National Gallery of Canada’s 1968 Heart of London exhibition in all of his files and bibliographic lists.

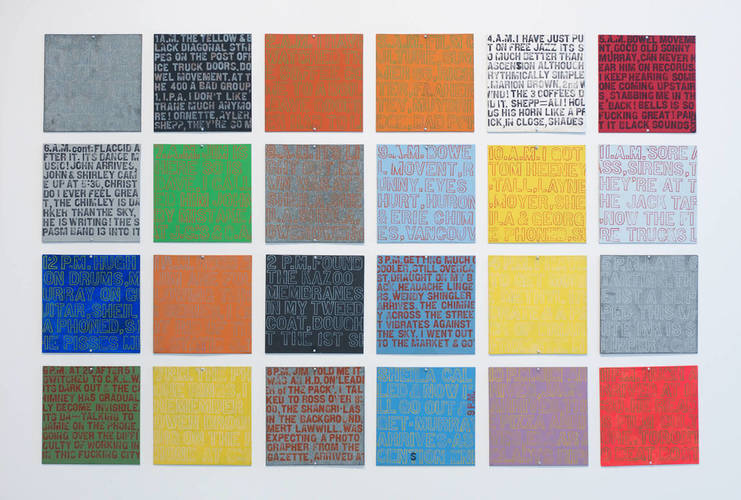

Greg Curnoe, 24 Hourly Notes, December 14–15, 1966

Stamp pad ink and acrylic on galvanized iron, 24 panels, each 25.4 x 25.4 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Curnoe’s patriotism overlaid with anti-Americanism led to controversy and censorship. The 1968 removal of his mural from the Montreal International Airport in Dorval, Quebec, because of anti-American statements is still one of the best-known examples of censorship in Canadian art history. Several months later, three panels of 24 Hourly Notes, December 14–15, 1966, were removed from an exhibition in Edinburgh because of “indecent” words. When the same work was exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa in 1970, a member of Parliament asked the prime minister, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, to have it removed. The work remained on exhibition. Both these issues resulted in significant national media coverage, including defensive responses from Curnoe.

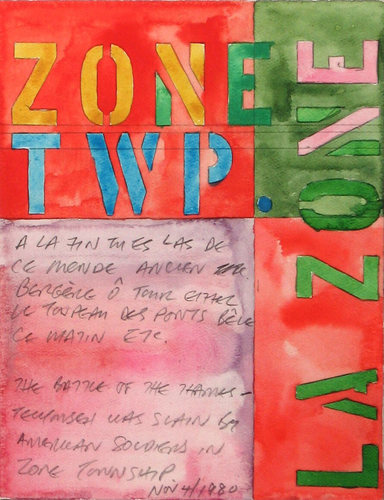

Greg Curnoe, Tecumseh/Apollinaire, November 4, 1980

Watercolour and pencil on paper, 23 x 18 cm, private collection

Toward the end of his career, Curnoe began to realize the ultimate irony of the cultural imperialism of his own British ancestors. He had probably become more aware of Indigenous history in Canada from his friend and mentor Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979), an expert in Indigenous pictographs. While Curnoe made earlier references in his work to Métis leader Louis Riel and the Shawnee hero Tecumseh, who lost his life close to London in 1813 at the Battle of the Thames, it was not until he began researching the pre-colonial history of his property at 38 Weston Street in London that a new understanding of Canadian identity began to emerge. As literary and cultural critic Frank Davey noted, “[Curnoe] felt strongly that as a white individual he had benefitted directly from the injustices First Nations people had suffered and that a major part of that benefit was hidden in the Canadian ‘forgetting’ of thousands of years of First Nations social development and inhabiting of the land.”

This Essay is excerpted from Greg Curnoe: Life & Work by Judith Rodger.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix