No Canadian painter offered a more disparate and ultimately controversial take on his country than William Kurelek (1927–1977). He portrayed Canada as a mosaic of diverse but harmonious cultures that thrived despite historical inequalities, a harsh environment, and a vast, unyielding geography. While creating such scenes, Kurelek also depicted apocalyptic and punishing scenes of disaster—works that raised his critics’ ire.

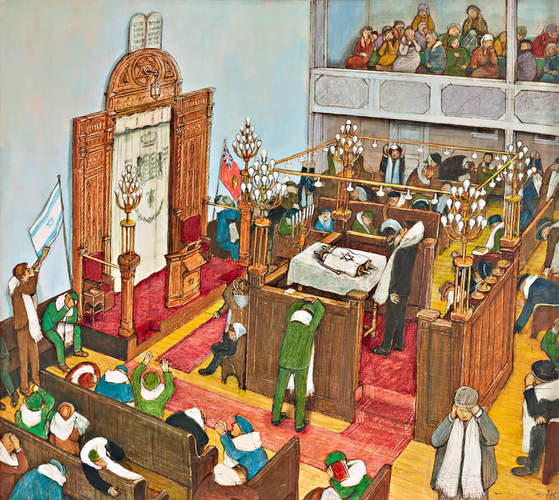

William Kurelek, Yom Kippur, 1975

Mixed media on board, 50.8 x 57.2 cm, UJA Federation of Greater Toronto. Used as an illustration in William Kurelek and Abraham Arnold, Jewish Life in Canada (1976), 32.

That a certain facet of Kurelek’s creative output was, and remains, popular is easy to understand. His imagery, whether of Ukrainian immigrants toiling on the prairie or of Jewish family life in Montreal, as in the illustration Yom Kippur, 1975, confirmed a progressive view of Canadian society that was strongly resonant between the late 1960s and early 1970s. Yet this was only one aspect of Kurelek’s art.

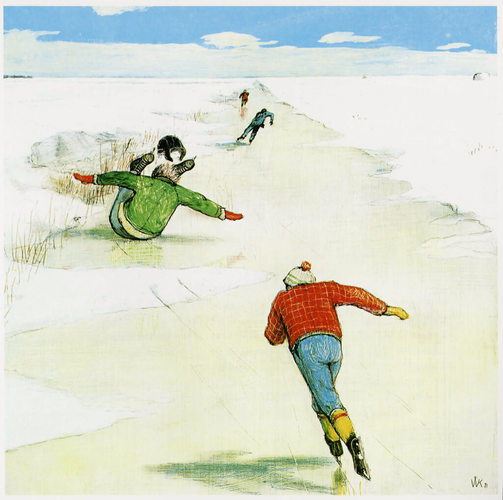

Throughout his career, Kurelek was never merely the naive, nostalgic, “happy Canadian” who wrote and illustrated award-winning children’s books. As a conservative Roman Catholic living with the looming threat of nuclear war in the 1960s, he believed that a manmade but divinely ordained “purgative catastrophe” was close at hand. And yet though he “damned with terrifying fervor . . . often with disturbingly gruesome images,” as critic Nancy Tousley observed, his “nostalgic side . . . and the work he considered to be ‘potboilers,’” such as his illustrations for A Prairie Boy’s Winter (1973) and A Prairie Boy’s Summer (1975), supported his popularity in the public imagination.

William Kurelek, Skating on the Bog Ditch, 1971

Approximately 33.7 x 33.7 cm, private collection. Used as an illustration in William Kurelek, A Prairie Boy’s Winter (1973).

As Kurelek’s dealer, Avrom Isaacs, believed, his decision to “put God first” made many within the secular art community apoplectic. Some argued that Kurelek’s moral didacticism interfered with the artistic integrity of his work. Others claimed his views were fraudulent. “Where Kurelek fails miserably,” journalist Elizabeth Kilbourn wrote in 1963, “is when he attempts to paint subjects which he knows about only from dogma and not from experience, where in fact he is a theological tourist in never, never land.” Kilbourn’s sentiments were echoed by critic Harry Malcolmson, who three years later penned what became the most infamous rebuke: “the problem with these pictures is that they flow from Kurelek’s imaginings and not from what he knows.” Malcolmson urged Kurelek to concentrate on farm paintings that reflected his upbringing.

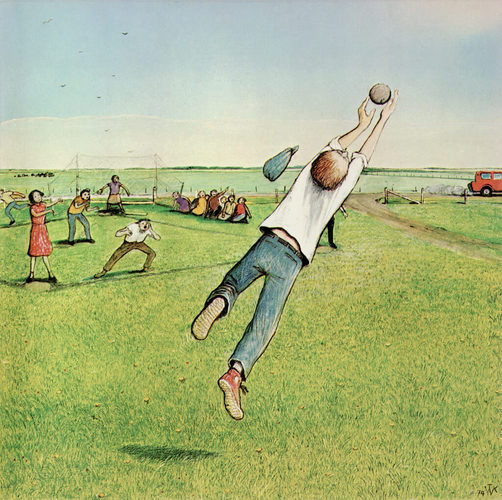

William Kurelek, Softball, 1974

Mixed media on Masonite, approximately 33.7 x 33.7 cm, Art Gallery of Windsor, permanent loan from private collection of Hiram Walker and Sons Limited, Walkersville. Used as an illustration in A Prairie Boy’s Summer (1975).

Kurelek’s response to his critics was characteristically indirect. According to his wife, Jean Kurelek, “He was sensitive to criticism but never liked to confront his critics in person,” and would publish a rebuttal or write them a letter. To Malcolmson he explained the source of his conviction: “Our civilization is in crisis and I would be dishonest not to express my concern about my fellow man.” And he added:

Did Hieronymus Bosch, a recognized master in representation of Hell himself go to Hell, and come back before he tackled it? No one has come back from the dead to record his experiences there and yet great classical writers like Milton and Dante waded right into it. Obviously they must draw their experience of those things partly from similar earthly experiences partly from personal or mystical intuition.

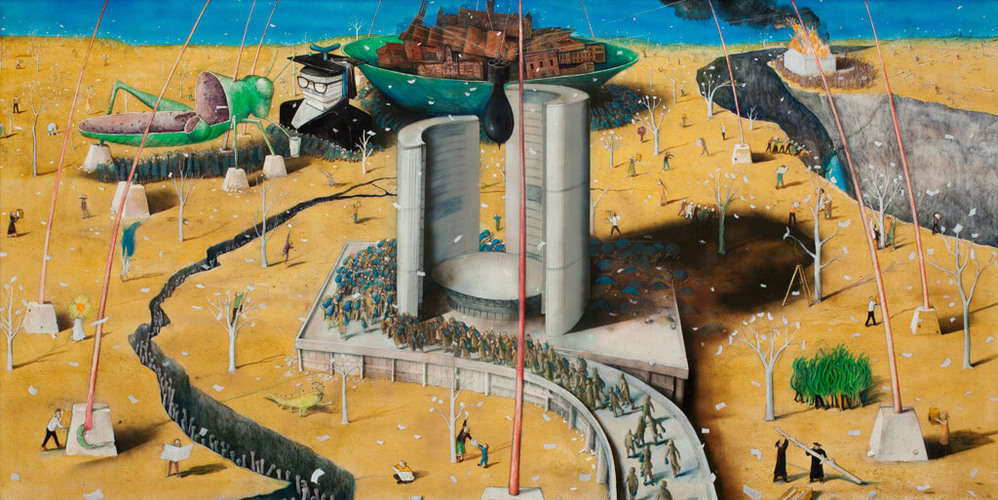

William Kurelek, Harvest of Our Mere Humanism Years, 1972

Mixed media on Masonite, 122 x 244 cm, Manulife Art Collection, Toronto

Kurelek ultimately regarded his art as existing outside the contemporary art world, and he unapologetically aligned his didactic “message” paintings, such as Dinnertime on the Prairies, 1963, with the religious and genre art of the Northern Renaissance. Though Kurelek’s work was a product of his Christian world view, the “somber, menacing quality” of it aligned naturally with the social anxiety and existentialism common in the art world during the Cold War era.

William Kurelek, Dinnertime on the Prairies, 1963

Oil on Masonite, 44.7 x 72 cm, McMaster Museum of Art, Hamilton

Despite Kurelek’s detractors, he earned immense respect from secular peers such as Dennis Burton (1933–2013) and Ivan Eyre (b. 1935). Moreover, critical credit from the media and museum professionals came in 1962 after the internationally respected director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Alfred H. Barr Jr., acquired a Kurelek painting for the institution’s collection. While Kurelek had his critics, the mainstream press exploded with accolades for the artist following his inaugural exhibition at Isaacs Gallery in Toronto in 1960.

This Essay is excerpted from William Kurelek: Life & Work by Andrew Kear.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans