Throughout his career, Canadian landscape painter and Group of Seven contemporary Tom Thomson (1877–1917) produced four hundred or more small oil paintings. They are found on wood panels, canvas board, plywood, and cigar-box lids in the plein air style. These were spontaneous, quickly executed sketches that became, for him, like drawings—the most immediate and intimate expression of an idea, a thought, an emotion, or a sensation. Based on his observations of a host of phenomena—sunsets, thunderstorms, and the northern lights—in Algonquin Park and around Georgian Bay, the works are a unique visual diary.

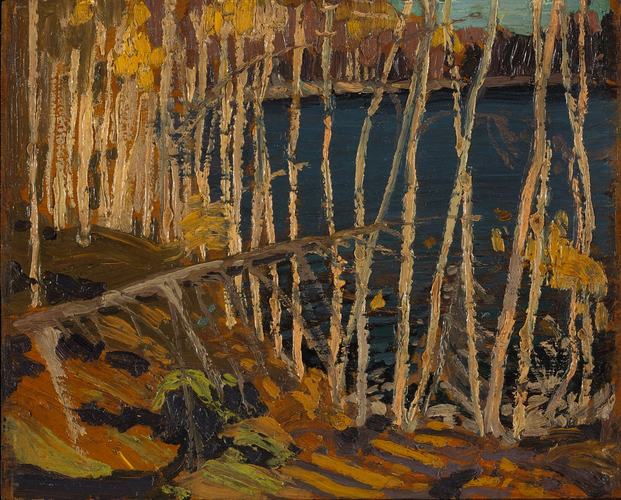

Tom Thomson, Autumn Foliage, 1915

Oil on wood panel, 21.6 x 26.8 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Thomson’s artistic path was not always straight. To consider his varied and energetic sketches in total invites us to trace certain trends in his oeuvre. Fire Swept Hills is an agitated and chaotically messy elegy to what was once a mature forest: Thomson’s reaction to the land after fire has swept through and ravaged it. Charred spindles of trees standing precariously like lifeless skeletons remind viewers constantly of fire and destruction. In the lower half, a tumble of paint crashes over rocks and more burnt trunks and branches like a wild cataract. Blood reds, blues, ash greys, and whites, all jumbled and mashed violently together, complete its statement of confusion and disorder. In Cranberry Marsh, meanwhile, the normal landscape conventions of his earlier work begin to fade, his hues become more vibrant, and his compositions, while still recognizable as subjects, become battlefields for layers of close-hued or clashing paint.

Tom Thomson, Fire-Swept Hills, 1915

Oil on composite wood-pulp board, 23.2 x 26.7 cm, The Thomson Collection, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

These “drawings in paint” have long been considered the core of Thomson’s work. Most of them were not done as studies for larger canvases but as complete works in themselves. He was satisfied with these small gems because he realized, as did his mentors J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932) and Lawren Harris (1885–1970), that they would not translate to a large canvas without losing the intimacy that characterizes them profoundly. Only a dozen or so, including The Jack Pine, 1916–17, and The West Wind, 1916–17, were ever realized as large canvases.

Tom Thomson, Cranberry Marsh, 1916

Oil on wood panel, 21.9 x 27 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

The Haystack paintings by Claude Monet (1840–1926) or the large cut-paper collages by Henri Matisse (1869–1954) serve similar ends to Thomson’s panels: they form an extensive suite of paintings with a constant theme. Consistent in style and with a palette of strikingly original colours, the sketches were created with a specific intent and executed in a short window of opportunity. At one point Thomson said he wanted to produce an oil sketch a day of Algonquin Park’s changing scenes, shifting with the weather and the seasons.

Tom Thomson, Blue Lake: Sketch for “In the Northland,” 1915

Oil on wood, 21.7 x 26.9 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

In Canadian art, the exquisite colour drypoints by David Milne (1882–1953) provide a coherent, related body of work. In literature, a similar project might be a suite of poems, such as Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets linked by their theme of heartache, longing, and uncertainty, or Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese, 44 sonnets written for her husband, Robert. Thomson’s small panels are, indeed, like love sonnets to the landscape of Algonquin Park and the idea of the North.

Tom Thomson, In the Northland, 1915–16

Oil on canvas, 101.7 x 114.5 cm, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

This Essay is excerpted from Tom Thomson: Life & Work by David P. Silcox.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix