London, Ontario, artist Greg Curnoe (1936–1992) created few works that do not include text of some kind. This artistic development had its genesis in Curnoe’s childhood: he was given a rubber stamp set as well as small rubber letters that were set in a wooden three-line holder, and he produced occasional newsletters with his cousin Gary Bryant, who had a drum printing press. Curnoe also experimented with date stamps discarded from his father’s office. He explained, “It was so natural for me to associate type and text with a picture. And I quickly learned there are things you can do with a text that you can’t do with a picture.”

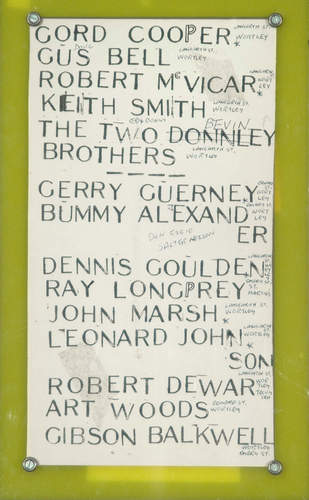

Greg Curnoe, List of Names from Wortley Road School, 1962

Stamp pad ink and ball-point pen on paper, 33 x 18 cm, McIntosh Gallery, Western University, London. The two “P”s and the lower case “c” are hand drawn, rather than stamped, perhaps because these letters were missing from the stamp set.

In 1961 Curnoe bought a new rubber stamp set, the first of many sets with uppercase letters that he used over the years. His early stamped works were lists: for example, lists of names of boys he grew up with. These were often very simple—black words stamped from individual letters combined with “found” texts. He also began the practice of making unique artists’ books: his seventy-one-page Rain and seventy-eight-page The Walk, both from 1962, have been acknowledged as the first artist books in Canada. Curnoe made over a dozen such works, perhaps as a more intimate and portable form of working with words and images. Like his paintings, most of these were diaristic, recording his daily thoughts and observations.

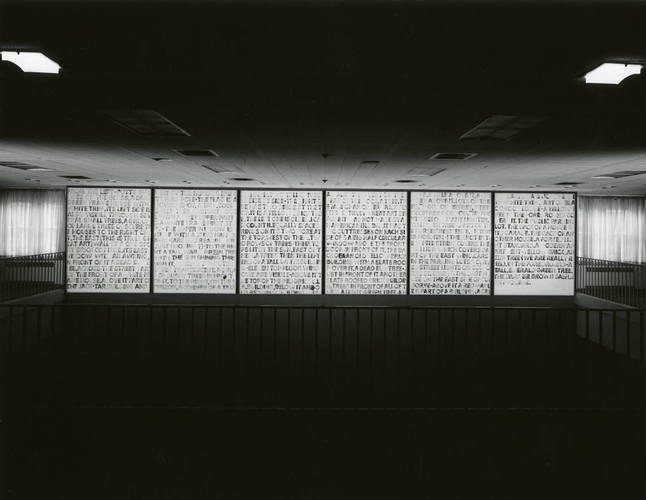

Installation view of Greg Curnoe, View of Victoria Hospital, First Series: #1–6, 1968–69

Rubber stamp and ink over latex on canvas; six canvases, each 289.6 x 228.6 cm; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, installation view unknown. Greg Curnoe stamped this non-figurative word description of his view of Victoria Hospital from one pane of his studio window. It was the first in a series of four works.

In 1968 Curnoe stamped the monumental six canvases of View of Victoria Hospital, First Series: #1–6. As art critic John Noel Chandler noted, the significance of this text series cannot be overstated: “Perhaps what is most novel and striking about what Curnoe has done is that by portraying the physical landscape with words, which are more abstract than pictures of things (at least in a phonetic language like our own), while at the same time making his language as simple and concrete as possible, Curnoe has accomplished the very interesting paradox of making pictures which simultaneously are abstract and concrete, making one reconsider the value of the dualism.”

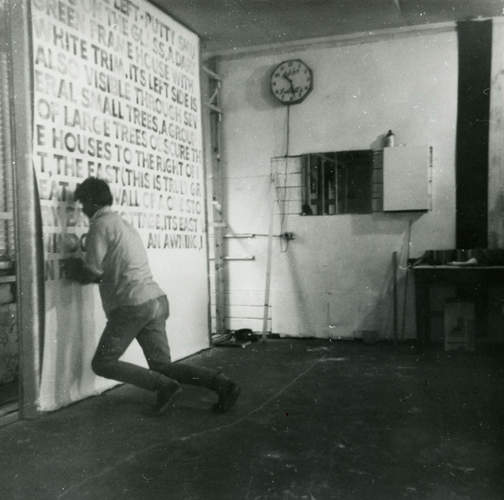

Greg Curnoe creating View of Victoria Hospital, First Series: #1–6, 1968–69, photograph by Pierre Théberge. Pictured is #1 in progress, September 1, 1968. Curnoe had to climb up and down ladders carrying individual stamps loaded with black ink, which he pressed forcefully onto white primed canvas that had been stapled to rubber carpet padding tacked to a sheet of plywood.

Text in Curnoe’s work was stamped, stencilled, embossed, or handwritten, with the break in the lettering determined by the size of the support. Curnoe explained, “I discovered that a sans serif typeface isn’t as legible as the more traditional serif faces. In other words, the letters stick out, they don’t disappear. It makes you look and read at the same time.”

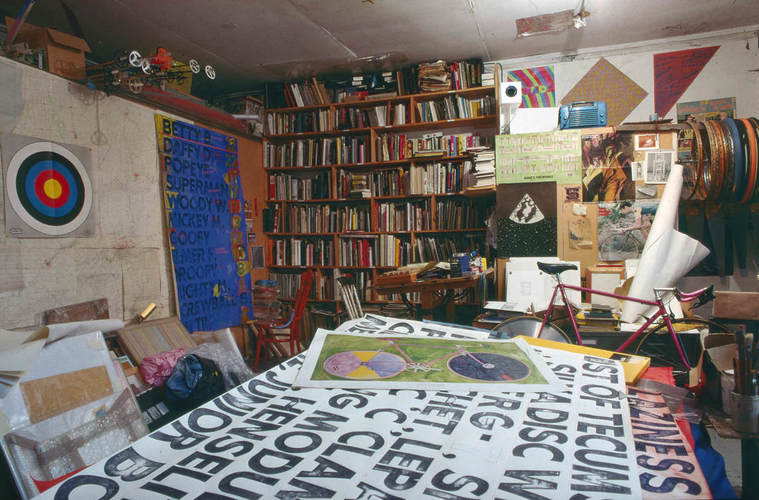

Curnoe’s studio in 1988, photograph by Ian MacEachern.

Curnoe was himself an omnivorous reader, and he amassed a large library over the years. Poetry anthologies and exhibition catalogues vied for space with atlases, novels, art books, and catalogues of bike parts. A novel that had a lasting influence on his work was The Voyeur (1955) by French writer and filmmaker Alain Robbe-Grillet, whose emphasis on precise language with an absence of metaphor was the literary equivalent of the visual style Curnoe was developing in the early sixties. Curnoe noted: “It is still one of my favourite novels and served to confirm my interest in using simple language and simple direct description.”

This Essay is excerpted from Greg Curnoe: Life & Work by Judith Rodger.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans