A carver based in Cape Dorset, Inuit artist Oviloo Tunnillie (1949–2014) created highly personal work in which expressive postures capture nuances of feeling. She is notable because few of her Inuit artist peers address such subjects as inner emotional states and grief. Other sculptors of her era—for example, Osuitok Ipeelee (1923–2005) and Kiugak Ashoona (1933–2014)—most typically favoured depictions of Arctic animals, domestic and hunting scenes, the sea spirit Taleelayu, shamanic transformations, and episodes from well-known legends and stories.

Oviloo Tunnillie, Oviloo and Toonoo, 2004

Serpentinite (Kangiqsuqutaq/Korok Inlet), 22.2 x 20.3 x 24.1 cm, signed with syllabics, collection of Barry Appleton

Human figures were impersonally dressed in culturally explicit fur clothing and were engaged in activities relating to pre-settlement living. Depictions of single human figures were rare and unemotionally engaged in an implied activity. Women were usually shown in their maternal roles with a child or children. The deep emotional expression conveyed in Oviloo’s work, as in such sculptures as Repentance, 2001, transcends the cultural or traditional while also speaking deeply to the artist’s own experiences.

Oviloo Tunnillie, Grieving Woman, 1997

Serpentinite (Tatsiituq), 35 x 12.5 x 11.3 cm, signed with syllabics, Winnipeg Art Gallery

The tragic episode of the death of her beloved father, Toonoo, must have contributed to Oviloo’s several self-portraits of grieving women. In 1969 Toonoo was shot to death by Mikkigak Kingwatsiak, the husband of Toonoo’s daughter Nuvalinga, in what was believed at the time to be a hunting accident. This shock re-emerged twenty-five years later when Mikkigak confessed to murdering Toonoo. Grief at her father’s death is the subject of Oviloo and Toonoo, 2004, in which the memory of him appears as a small figure that seems to be trying to reach his weeping daughter from a distance.

Oviloo Tunnillie, Woman Covering Her Face, 2000

Stone, 37.2 x 14.6 x 7 cm, collection of Jane Ross

In her work, Oviloo also addressed the suicide, in 1997, of her thirteen-year-old daughter, Komajuk. Mental anguish is expressed in a number of Oviloo’s sculptures from this date on, beginning with Grieving Woman, 1997, a quiet work that expresses profound grief through the body language of the female figure who moves slowly forward with head bowed and one hand pressed to her forehead. No facial expression is necessary to capture the figure’s anguish. In 2000, Oviloo created a nude and vulnerable Crying Woman, her face buried in arms folded on knees drawn up into herself. In both of these, covered faces cut the figures off emotionally from the outside world and create focused images of isolation and sadness.

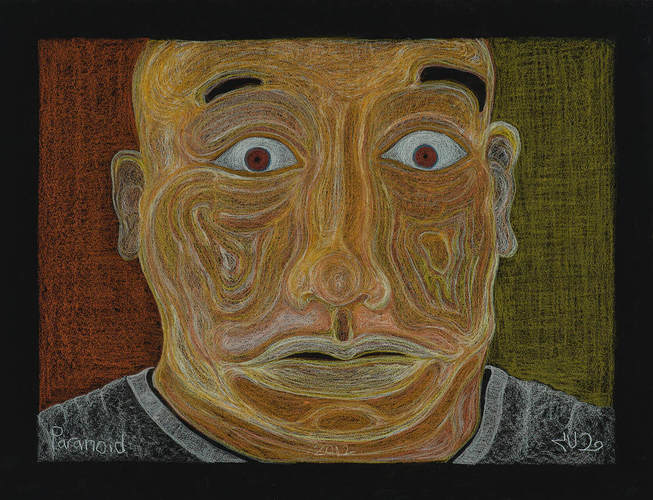

Jutai Toonoo, Paranoid, 2012

Graphite, coloured pencils on paper, 50 x 65 cm, Winnipeg Art Gallery

The unorthodox expression of inner states of mind was also a powerful feature of the graphic art and sculpture of Oviloo’s brother Jutai Toonoo (1959–2015), who may have been influenced by his sister. Both artists uniquely created human forms and figures devoid of a narrative context. Jutai’s non-narrative images of human heads and figures, such as Paranoid, 2012, are deeply personal and often portray restless sleep or dreamlike states. A bipolar disorder influenced his fierce independence from conventional subjects. Both he and Oviloo created their unique imagery in a community that had deep roots in culturally specific and narrative art forms.

This Essay is excerpted from Oviloo Tunnillie: Life & Work by Darlene Coward Wight.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans