Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) was the only member of the Group of Seven based in Western Canada. He was also heir to ideas engendered by two powerful artistic developments from the nineteenth century, the Arts and Crafts movement and Art Nouveau, and he drew from these in his representations of the prairie light and landscape.

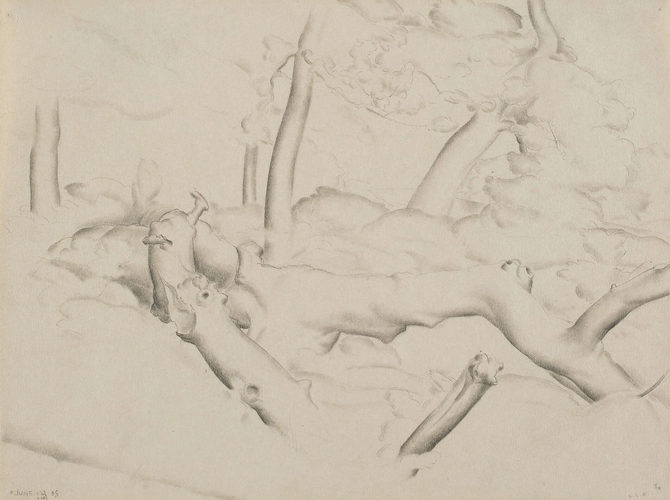

Graphite on wove paper, 22.9 x 30.2 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

FitzGerald valued the anti-industrial ethos promulgated by the members of the Arts and Crafts movement, who advocated handmade artistic expressions using a wide variety of media. Art Nouveau, in which architecture and sculptural forms could be transformed into seemingly living, growing plant forms, would have appealed to FitzGerald’s belief that nature was animated by a vital, living force. As he put it: “The seeing of a tree, a cloud, an earth form always gives me a greater feeling of life than the human body. I really sense the life in the former, and only occasionally in the latter. I rarely feel so free in social intercourse with humans as I always feel with trees.”

Graphite on paper, 31 x 36.6 cm, Winnipeg Art Gallery

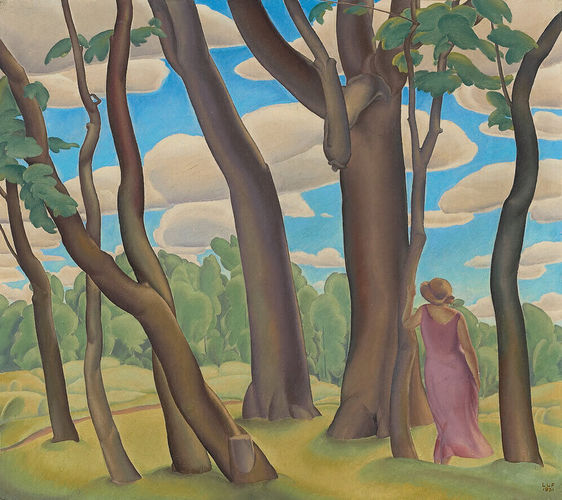

Like the later artist Jack Chambers (1931–1978), who would articulate a theory of “perceptual realism” in the 1960s, FitzGerald was intensely devoted to capturing the world he saw around him. Both artists wished to convey a heightened sense of what it means to look at the ordinary elements of one’s surroundings, whether it be a landscape, backyard, or objects on a windowsill. And each artist gave special emphasis to light as an essential component of perception. It is FitzGerald’s genius at representing the prairie light—moving away from the blending effects of atmospheric light in his early Impressionist-inspired works such as Figure in the Woods, 1920, to a light that isolates “compositional elements … stressing their formal relationships” in a mature work such as At Silver Heights, 1931—that sets him apart from any other artist of his generation.

Oil on canvas, 91.4 x 61 cm, private collection

Canadian abstract painter Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) immediately seized on the notion of the vital quality in FitzGerald’s work when he first acquired a pencil sketch from the artist’s 1928 exhibition at the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto. Presumably he is referring to this drawing in his 1949 lecture: “[I]t was a very fast drawing of a bulbous, twisted tree. Looking at it often I came to think that the tree might just as well be a carrot or an elephant—in other words it was not so much an object as an attempt to search out the organization of any living thing. It was not really a thing, it was a verb—a picture of living!”

Oil on canvas on board, 35.8 x 40.2 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

FitzGerald did not publicly or privately align himself with any scientific, religious, or philosophical position, which suggests that his views on art and nature were not codified but rather evolved over time in accordance with what he thought it meant to be an artist. The advice he gave to his students at the Winnipeg School of Art, recorded in notes from a lecture possibly given in 1933, articulates his artistic credo: “It is necessary to get inside the object and push it out rather than merely building it up from the outer aspect. So appreciate its structure and living quality rather than the surface only. Through this way of looking at a thing elimination takes place and only the essential things appear.” The goal was to gain “an appreciation for the endlessness of the living force which seems to pervade and flow through all natural forms even though they seem on the surface to be so ephemeral.”

This Essay is excerpted from Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald: Life & Work by Michael Parke-Taylor.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans