When Norval Morrisseau arrived on the Canadian art scene in 1962 with his exhibition at the Pollock Gallery in Toronto, he sparked a national news event and commenced a rupture in Canadian art.

At a time when enforced assimilation was national policy and First Nations had only recently been accorded the right to vote in federal elections, Morrisseau’s paintings stood out because few Indigenous people made art that was viewed as contemporary within the narrow framework accepted in mainstream cultural circles. Most Indigenous artworks were considered artifacts, and were displayed in ethnographic museums rather than art galleries.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the federal government had invested heavily in the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, and its director, James Houston (1921–2005), worked hard to market Inuit soapstone carvings, drawings, and prints as modern artistic expressions. The Canadian Guild of Crafts also supported Indigenous arts, but its shows were typically held in venues other than art galleries. Without government intervention, there appeared to be little appetite for Indigenous art in galleries in the early 1960s.

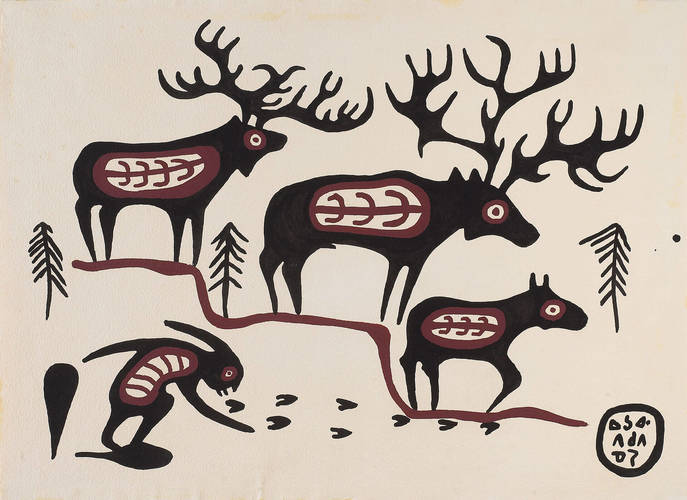

Morrisseau’s 1962 exhibition at the Pollock Gallery marked a turning point because of the artist’s racial identity and because he was creating contemporary art. Works like Moose Dream Legend, 1962, were hailed as both primitive and modern by critics at the time. Morrisseau’s work demonstrated clear links to the oral narrative traditions of the Anishinaabe in its process and its focus on animals and spirit-beings, but also commented on how 150 years of the assimilationist policies of Canada’s Indian Act, which included residential schooling, had visibly erased Indigenous issues and understandings from Canadian public life.

Oil on wove paper, 54.6 x 75.3 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Morrisseau’s entry onto the art scene marked a turning point. As the civil rights movement gained momentum in the United States and inspired Native Americans to push for greater equality, and as Indigenous populations in Mexico advanced similar struggles, Canadian Indigenous peoples also organized and confronted government practices.

In June 1969 the release of the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy (a document commonly known as the 1969 White Paper) by the Pierre Trudeau government in Ottawa triggered a series of political events. These resulted in the creation of the National Indian Brotherhood and regional factions that challenged the federal government to make changes to a system that was stacked against First Nations people. Artists joined forces, too, to change the racialized ways art was being exhibited in Canada.

In 1967 Indigenous artists were commissioned to create the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67, a moment now considered pivotal in acknowledging activism and awareness of Indigenous issues in Canada. Morrisseau was part of a group called the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., which was established by Odawa artist Daphne Odjig (1919–2016) in Winnipeg in 1973 and labelled the Indian Group of Seven by the press.

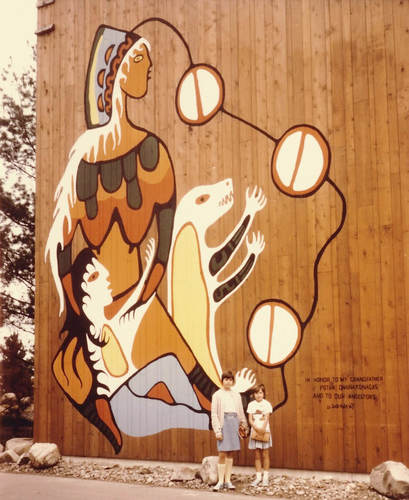

Norval Morrisseau’s mural for the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67.

Commissioning Indigenous artists to design the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 is now considered a pivotal step in acknowledging activism around and awareness of Indigenous issues in Canada, but Morrisseau left the project when government officials deemed his mural design of bear cubs nursing from Mother Earth to be too controversial.

Despite Morrisseau’s ground-breaking success in 1962, it would take another thirty years before Morrisseau’s work became part of the National Gallery of Canada’s collection. As early as 1972 anthropologist and artist Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979) had tried to persuade the National Gallery of Canada to add works by Morrisseau to its collection, but his effort was unsuccessful. At the time, the ethnographic Canadian Museum of Man, then in Ottawa (now the Canadian Museum of History, Hull, Quebec), was the Canadian institution that collected contemporary Indigenous art, whereas the National Gallery bought works by non-Indigenous Canadian artists.

Not until 2006 did the National Gallery purchase work by Morrisseau and make him the subject of its first retrospective exhibition devoted entirely to an Indigenous artist. As art critic Paul Gessel, writing in the Ottawa Citizen, noted under the front-page headline “An Art Pioneer Makes His Final Breakthrough,” “Who would be the first Native artist to be given a show akin to the exhibitions granted such ‘white’ Canadian artists as Tom Thomson and Emily Carr? The consensus among the Aboriginal art community was that Norval Morrisseau…had to be the one.”

Norval Morrisseau in front of his painting Androgyny, 1983, at the opening of his solo exhibition Norval Morrisseau—Shaman Artist at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2006. Parkinson’s disease confined Morrisseau to a wheelchair in the last years of his life.

This media coverage repositioned Morrisseau as a major Canadian artist, validated Indigenous art as contemporary, and helped end the practice of separating Indigenous from mainstream artists in public discourse.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans