As an abstract painter in the 1950s, Paterson Ewen (1925–2002) embraced the expressive, exuberant brushstrokes typical of some of the Automatistes and Abstract Expressionists. In his untitled pastels on Fabriano paper in the early 1960s, he was fascinated to see how “the texture of the paper showing through the pastel suggests that it’s happening now, that it is alive.” He was attracted to the physical process of making art; of the mixed-media works he began in the 1970s, he said: “The work became a lot more fun when I was able to start nailing stuff on it.” This physicality found its most potent expression in Ewen’s handmade-paper works, such as Moon, 1975, and especially in his signature gouged plywood works, such as Moon over Water, 1977.

Homemade blue paper and acrylic, 48.8 x 49.9 cm, McIntosh Gallery, London. Printmaker Helmut Becker taught Ewen to make his own paper in the early 1970s. Here, the bumps and grooves of the paper suggest the surface of the moon, and Ewen’s method of applying colour by holding his brush like a knife and stabbing the image mimics the violent forces by which the moon was created.

Ewen’s gouging technique, which combined painting, sculpture, and even woodblock printing, defined a new kind of gestural painting in Canada and internationally. Ewen described his process:

“I get an image in my head somehow or other, from someplace or other, and I live with that image for a while. . . . The image wants out, my hands and eyes are ready for the attack on the plywood, my intelligence exerts an automatic restraint, the adrenalin flows and the struggle begins.

“The physical beginning involves gathering materials and tools in advance of the struggle, wood, machine tools, hand tools, paint, and a myriad of things. A length of wire becomes rain, a piece of link fence becomes fog and so on, obviously a physical activity running parallel with the fermenting images in my head.

“Once I place the plywood on the sawhorses and touch a magic marker to the surface to begin a vague drawing of the image, the activity begins to accelerate. Drawing is followed by routing and thoughts of colours, textures, materials rotate in my mind . . . things get nailed on, glued on, inlaid, or stamped on by a homemade stamp. . . .

“Perhaps I can risk saying something that only the artist would know or dare to proclaim, and that is that once begun, the work cannot fail. This is so because I make it come out.”

Ewen subsequently applied colour using rollers and brushes, depending on the surface and the area to be covered, roughly following the pastel drawing that preceded the routing. For the plywood works, he used acrylic paint, which adhered better than oil-based paint and had muted hues that better revealed the untreated wood underneath.

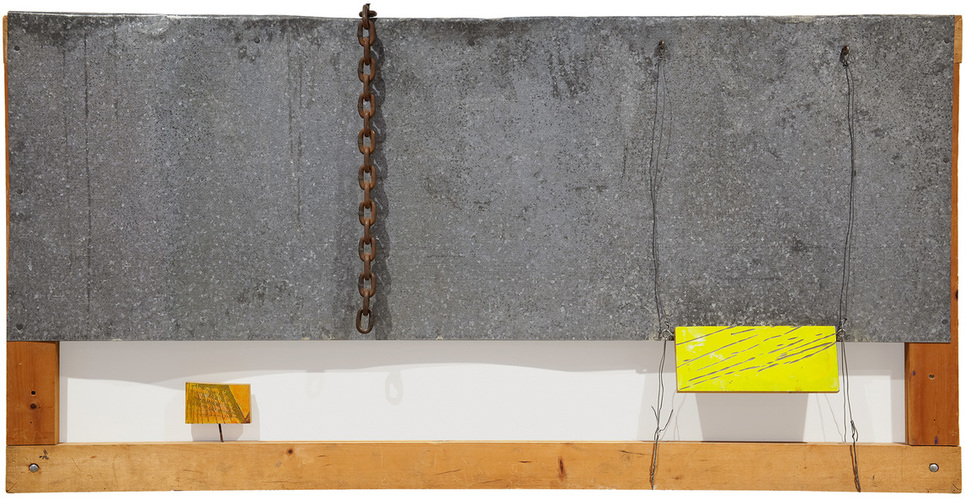

Steel bolts, wire and chain, galvanized steel, engraved linoleum, and wood, 94 x 183 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Ewen’s richly textured, animated surfaces make tangible the forces of nature. In essence, nothing in his work is still. Ewen understood that change is the only constant, and rarely does he depict an idyllic landscape devoid of movement. Rain falls and is blown by the wind; ocean currents are driven by underlying forces, as shown in Ocean Currents, 1977. The rotation of stars around Polaris, the phases of the moon, the comets, sunrises and sunsets, solar eclipses, and even galactic cannibalism, as in Cosmic Cannibalism, 1994, all speak of motion in the universe.

Acrylic and metal on gouged plywood, 243.5 x 235.9 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Whether it is the irregular patterns in the seemingly static Blackout, 1960, or the raw surface of the handmade paper in Coastline with Precipitation, 1975, or the deep gouges in plywood that recall those carved by insect larvae burrowing inside tree bark or those scoured by glaciers flowing over rock, Ewen reveals the mutability of the apparently immutable and makes us aware of unfamiliar forces within the familiar. His works appear to be undergoing transformation before our very eyes. As writer Shelley Lawson concludes, “The results are powerful work as rough-hewn and rugged as the Canadian landscape, as unmercifully omnipotent as the natural phenomena they represent and with a character as imposing yet sensitive as Ewen himself.”

This Essay is excerpted from Paterson Ewen: Life & Work by John G. Hatch.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans