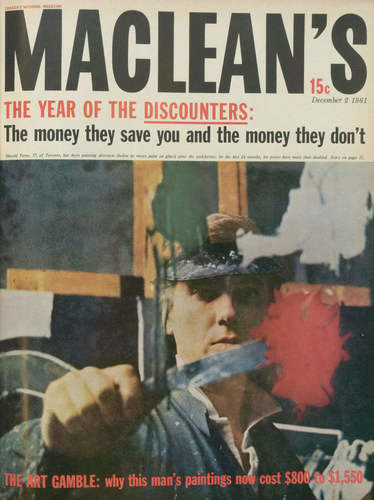

In 1961 Toronto painter Harold Town (1924–1990) made the cover of Maclean’s, and the following year the Toronto Telegram Weekend Magazine carried a two-part feature by his friend Jock Carroll, which included anecdotes about Town’s outrageous exploits. The press was fascinated both by his notoriety as a dandy and party animal and by his reputed earning power as “the hottest sales property in English-speaking Canada.”

Harold Town on the cover of Maclean’s magazine, December 1961.

Through the 1950s the growing concentration of wealth in Toronto had set off a local art boom. Openings at art galleries drew large, socially mixed audiences and regular press commentary. New dealers were emerging, willing to show young experimental artists and groom upcoming local art patrons, and lively interest in abstract art was spreading across Canada, generating debates on the relative merits of the art scenes in Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver.

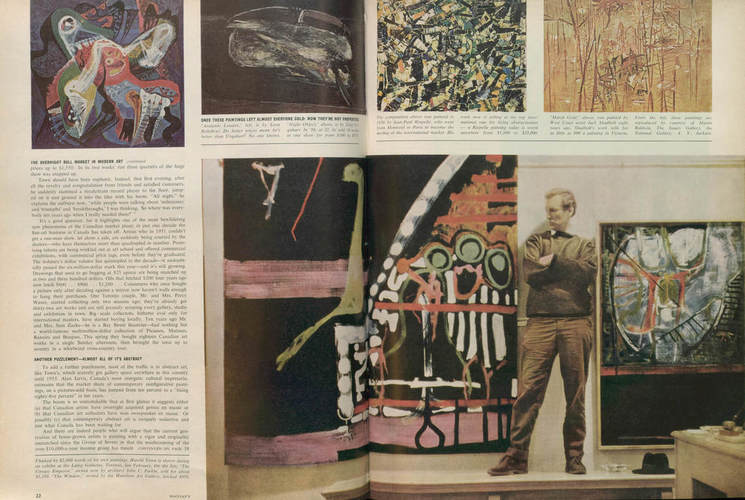

Harold Town featured in the issue’s provocative article “The Overnight Bull Market in Modern Art.”

Town, invited to represent Canada twice at the Venice Biennale and selected as one of 361 leading world artists by the curators of Documenta 3 in Kassel, Germany, in 1964, emerged as a leading figure in the new scene. By 1965 his large canvases were fetching up to $4,000, a record price for contemporary Canadian work, and he was dubbed the “artist with a tax problem.” In 1969 he was on the cover of the Canadian edition of Time magazine. Throughout the decade he was referred to as “synonymous with art in Toronto” or “Canada’s most famous artist.”

Harold Town with his paintings at the Mazelow Gallery in Toronto in 1967, photographed by John Reeves.

Town’s large canvases of the early 1960s precipitated frenzies of acquisition by corporate and private patrons, first at the Laing Galleries in 1961 and then at Town’s famous double openings in 1966 and 1967 in Toronto, when he launched distinct bodies of work simultaneously the Mazelow Gallery and the Jerrold Morris International Gallery. Young newspaper critics found his work exciting to decode, and Robert Fulford and Elizabeth Kilbourn became keen champions, reviewing his shows and contributing exhibition catalogue essays.

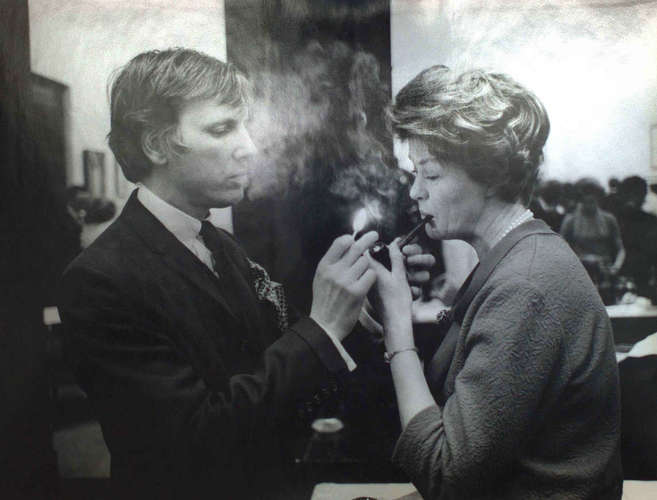

Town and Janet Barker at an Art Gallery of Ontario reception in 1967, photographed by John Reeves.

Proof of Town’s status as an established member of Toronto’s cultural elite was his membership in the exclusive (and oddly spelled) Sordsmen’s Club. Defined in its charter as “devoted exclusively to the pursuit of pleasure, superb food, fine wine, exceptional women, and conversational excellence,” the club was limited to fifteen permanent members, including author and broadcaster Pierre Berton, publisher Jack McClelland, architect John C. Parkin, Alan Jarvis (then editor of Canadian Art magazine and national director of the Canadian Conference of the Arts), and CBC TV producer Ross McLean.

Harold Town with his daughters Heather and Shelley in 1966, photographed by John Reeves.

The painter wrote book reviews for the Globe and Mail, and contributed a regular cultural column to Toronto Life magazine during 1966–71. He became engaged in the conflicts that attended the rapid pace of urban development. Town supported Mayor Phil Givens, who led the public fundraising campaign to purchase the sculpture by Henry Moore (1898–1986) now in front of Toronto City Hall and acquired contemporary Toronto canvases for the building’s interior (a large Town was hung behind Givens’s desk). Town protested against the inroads of the automobile and the destruction of Toronto’s historic buildings; he contributed posters for the 1969 campaign opposing the Spadina Expressway and for reformer David Crombie’s 1972 mayoral campaign and bid to save Toronto’s neighbourhoods. With his sharp wit, conversational skills, and wide reading, Harold Town defended abstract art in the face of Canada’s conservatism, injecting glamour and élan into Toronto’s cultural scene.

This Essay is excerpted from Harold Town: Life & Work by Gerta Moray.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans