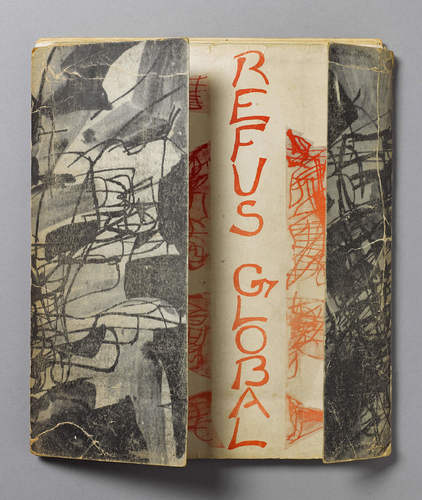

When Paul-Émile Borduas, leader of the Montreal-based avante-garde Automatiste movement composed the manifesto Refus global (total refusal) in 1948, he and his colleagues had every intention of shaking up the cultural and moral certainties of Quebec society. However, he did not expect the many and far-reaching personal and public consequences of its publication, including the fact that it would be credited as launching the province’s Quiet Revolution in the 1960s.

The manifesto, first published in an edition of four hundred copies, went on sale at Montreal’s Librairie Tranquille on August 9, 1948

Borduas’s career had reached a turning point in 1938 when he discovered Surrealism and the works of the French writer André Breton (1896–1966), who gave him the idea of painting without having a preconceived idea—in a sense “automatically.” Around the same time he met a number of like-minded young artists and intellectuals who were keen to push the rigid boundaries of Quebec society. Under Borduas’s leadership these artists formed the group that came to be known as the Automatistes.

Determined to make their mark, and encouraged by Borduas’s student Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), who had signed the Surrealist manifesto Rupture inaugurale in Paris, the Automatistes initially decided that their third exhibition in Montreal would be accompanied by a manifesto. Borduas took on the task of writing the main text, but Bruno Cormier and Françoise Sullivan (b. 1925), as well as Claude Gauvreau and Fernand Leduc (1916–2014), also contributed. The publication included reproductions of paintings by members of the group and photographs of Claude Gauvreau’s theatre productions. In the end the group postponed the third Montreal exhibition of the Automatistes in favour of making an event out of the launch of the manifesto. Refus global was published in a first edition of four hundred copies printed on a Gestetner duplicating machine; the copies went on sale at the Librairie Tranquille in Montreal on August 9, 1948.

In the manifesto Borduas launched a frontal attack on the parochialism (esprit de clocher, as it was called) in Quebec, the stifling dominance of Catholicism, and the narrow nationalism of the provincial government under Premier Maurice Duplessis. The immediate consequence was Borduas’s suspension without pay from his position at the École du meuble, effective September 4, 1948. The provincial minister of youth and social welfare explained the decision as follows: “Because the writings and the manifestos [sic] he publishes, as well as his state of mind, are not conducive to the kind of teaching we wish to provide for our students.”

The repercussions of the manifesto’s publication extended far beyond Borduas’s career. His young (and not so young) disciples were also affected. Some, like Riopelle and Leduc and their respective partners, chose to leave Quebec for a life in France. Marcelle Ferron would later follow the same path. But others, those known as the “young brothers”—Marcel Barbeau, Jean-Paul Mousseau, and Claude Gauvreau—became even more interested in the political cause. Responding to the manifesto’s exhortation to “refuse to be confined to the barracks of plastic arts,” they sought to take their art and their ideas into the public domain, publishing polemics in journals and newspapers. Concerned that they were operating under an illusion with regard to the impact they could have on prevailing sensibilities, in 1950 Borduas wrote his essay “Communication intime à mes chers amis” (Intimate message to my dear friends), in which he recalls: “Poetical work carries a profound social potential, but [it] is realized slowly—for it has to be assimilated by a multitude of men and women with nothing to assist them but the power of the work itself.”

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans