The painter Alex Colville (1920–2013) had a passion for order, beginning with the underlying geometry of his image, a rigid skeleton of geometric relationships that dictated every aspect of his compositions. “Geometry seems to be a way into the process,” he said. “If I were a poet I would write sonnets. I would not do what you speak of as ‘free verse.’ I work within existing forms.” His work offers moments of stasis that anchor us in a chaotic world.

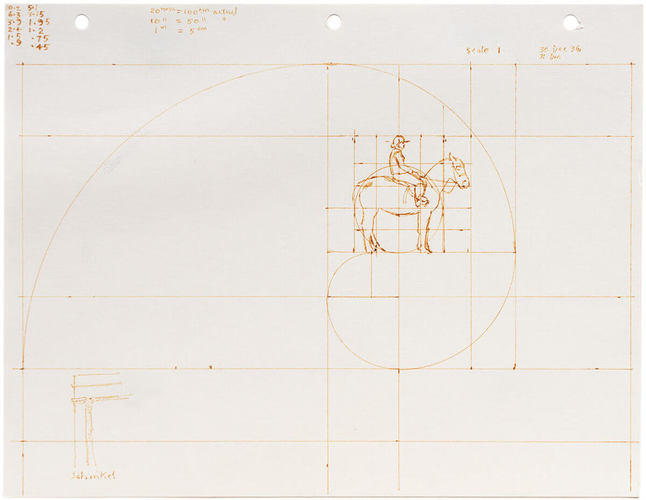

Alex Colville, Study for St. Croix Rider, December 30–31, 1996

Raw sienna ink on paper, 21.7 x 28 cm, private collection

In this study, Colville uses the golden section as the mathematical basis of his composition.

Colville’s experience as an official war artist during the Second World War and especially his assignment to document the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp brought him into contact with the full potential of human depravity. The war and its numbing effect profoundly impacted Colville’s work, in which he refuses to accept the eventual triumph of entropy and instead seeks stability, geometric order, and endurance despite knowing they are ephemeral.

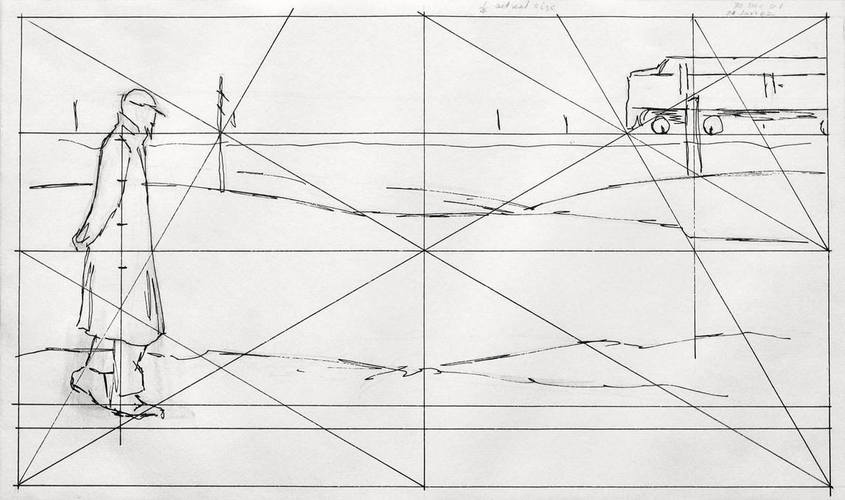

There are twenty-one studies for Colville’s painting Ocean Limited, 1962, in the collection of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. The sketches were primarily used to work out the geometric underpinnings of the major compositional elements: how the head of the walking figure and the train engine line up, the relative placement of the horizontal elements of the railway embankment and road, and the vertical elements of telephone poles and the walking figure in the foreground.

Alex Colville, Sketch for Ocean Limited, c.1961

Graphite and ink on paper, 15 x 24 cm, Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

Colville often based his paintings on the golden section, a mathematical sense of proportion that has been used in architecture and art from Ancient Egypt to today. As curator Philip Fry noted, Colville used geometry as a “regulatory system”—as a way of imposing coherent, predictable, and orderly relationships between objects in his compositions. Often borrowed from architecture, these systems could be relatively simple or more complex, as in the Modulor system of the modernist architect Le Corbusier (1887–1965) and the ratios derived from the mathematical sequence called the Fibonacci series, for example, in Study for St. Croix Rider, December 30–31, 1996.

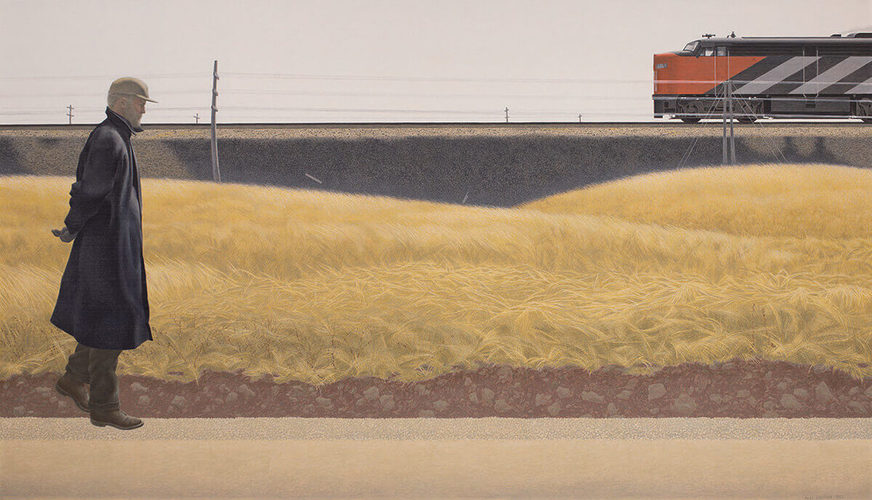

Alex Colville, Ocean Limited, 1962

Oil and synthetic resin on Masonite, 68.5 x 119.3 cm, Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

Colville’s meticulous sketches show how, before he began to paint, the image and the geometry evolved as he arrived at a composition that communicates the ideas and feelings he looked for. As art historian Martin Kemp writes: “Human proportionality, which is based on a system of head lengths beloved of Renaissance architects and more recently Le Corbusier, has an important role in these paintings that involve his cast of wordless characters.”

Nobel Prize–winning physicist Frank Wilczek sums up the persistent belief that a beautiful order underlies the apparent chaos of the world in a discussion of the Pythagorean aphorism, “All things are number”: “For the true essence of Pythagoras’s credo is not a literal assertion that the world must embody whole numbers, but the optimistic conviction that the world should embody beautiful concepts.”

Alex Colville, Traveller, 1992

Acrylic polymer emulsion on board, 43.2 x 86.4 cm, Art Gallery of Hamilton

In organizing the composition by use of “beautiful concepts” to establish an orderly underlying framework, Colville adds a sense of solidity to what at first appears as a scene taken from observation. Geometry determines the perspective, ensuring that the image, however much an invention, feels right to the eye. An almost subliminal sense of proportion and alignment conveys the underlying geometric order. Ultimately, Colville’s geometry is most important not for its specific angles, arcs, or correspondences, but for the foundational rigour that the balanced geometric framework gives to the image itself. Seeking order, one must banish chance.

This Essay is excerpted from Alex Colville: Life & Work by Ray Cronin.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans