Not only was William Notman (1826–1891) a pioneer of photography in Canada and one of the country’s most important artists—he was equally renowned for his business savvy. This fact is all the more impressive considering that Notman arrived in Montreal from Scotland in 1856 with no immediate source of income and no experience as a photographer. In two short years he expanded his first studio on Bleury Street into a larger and much more elegant space next door and moved his residence from above his business to offsite to Sherbrooke Street.

Notman & Sandham, William Notman Studio, 17 Bleury Street, Montreal, c.1875

Silver salts on paper, albumen process, 25 x 20 cm, McCord Museum

The year 1858 proved to be a fundamental turning point in Notman’s career. He was awarded the commission from the Grand Trunk Railway to document the building of the Victoria Bridge across the St. Lawrence River. This was a public project on a grand scale, and Notman wasted no opportunity to draw attention to his participation. He sent copies of his photographs to a wide array of journals and even produced a commemorative maple box of the photographs to present to Queen Victoria in 1860. In it, Notman mounted photographs in two lavish leather-bound portfolios with silver clasps. Never one to shy away from self-promotion, he supported a popular story that she was so pleased that she named him “Photographer to the Queen.”

Notman & Sandham, Notman & Sandham’s Room, Windsor Hotel, Montreal, 1878

Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, albumen process, 10 x 8 cm, McCord Museum

In 1860 Notman hired the established painter John Arthur Fraser (1838–1898) to lead the business’s art department and a young Henry Sandham (1842–1910) to assist. The department was responsible for painting backdrops, retouching negatives, cutting out individual figures and pasting them into composite groups, and hand-colouring prints. The work of the art department became an integral part of the studio’s appeal and of its competitive advantage in the marketplace.

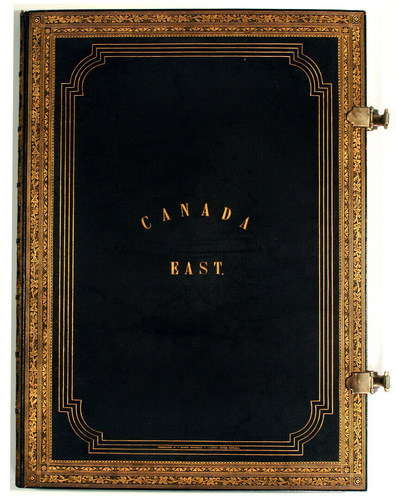

William Notman, Canada East, portfolio from the maple box, 1859–60

76.2 x 91.4 x 5.1 cm, McCord Museum. Notman made two of these leather-bound portfolios of photographs and stereographs, setting each in a maple box. One of these boxes was given to Queen Victoria and the other remained in his Montreal studio.

By 1864 Notman’s Montreal studio had thirty-five employees, both men and women, including photographers and artists, apprentices, studio and darkroom assistants, receptionists, bookkeepers, and dressing-room assistants. To some extent studio labour was divided according to class, skill, and gender. Working-class women, for example, had the dirty and laborious job of preparing paper and printing negatives, whereas middle-class women worked in the art department, mounting or retouching photographs. The account books show that the staff were decently compensated and that Notman kept them steadily employed even during periods of financial hardship. The loyalty Notman showed and expected from his staff was a crucial tool in building the business.

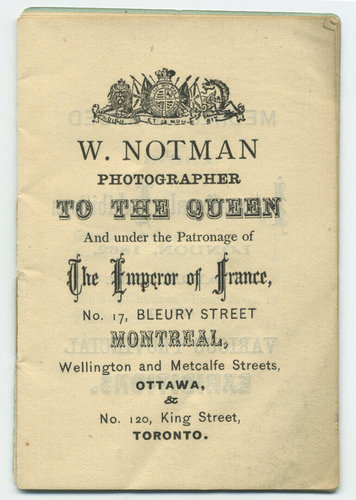

Opening page from the pamphlet Photography: Things You Ought to Know by William Notman, after 1867

Ink and letterpress, 9.3 x 6.4 cm, McCord Museum. A savvy marketer and self-promoter, Notman made sure that all materials coming out of his studio indicated that he was “Photographer to the Queen”.

From the earliest days of his studio, Notman and his photographers fanned out across the British territories and into the northeastern United States. Often they were fulfilling commissions or capturing landscape views to add to their growing collection that was available to tourists, locals, and other studios. In 1868, a year after Confederation, Notman established a studio in Ottawa and soon set up branches and partnerships in Toronto and Halifax, usually with a trusted associate in charge.

William Notman, Young Ladies of Notman’s Printing Room, Miss Findlay’s Group, Montreal, 1876

Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, albumen process, 10 x 13 cm, McCord Museum. This group of working-class women prepared paper and printing negatives in Notman’s studio.

Notman carefully nurtured talent in his studios and offered partnerships or managerial positions in the branches as a way of retaining skilled staff. He placed John Fraser in charge of his Toronto branch and called it Notman & Fraser. He offered a junior partnership in the Montreal studio to Henry Sandham in 1872, changing the firm’s name to Notman & Sandham. Always on the lookout for new opportunities, in 1869 Notman garnered a commission to produce student and faculty portraits at Vassar College in New York State. He developed this line of business quickly and eventually set up seasonal branches at Harvard and Yale. At the height of his empire in the 1880s, Notman’s name was on twenty studios. The scale and reach of his photographic output was unparalleled in nineteenth-century Canada.

This Essay is excerpted from William Notman: Life & Work by Sarah Parsons.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans