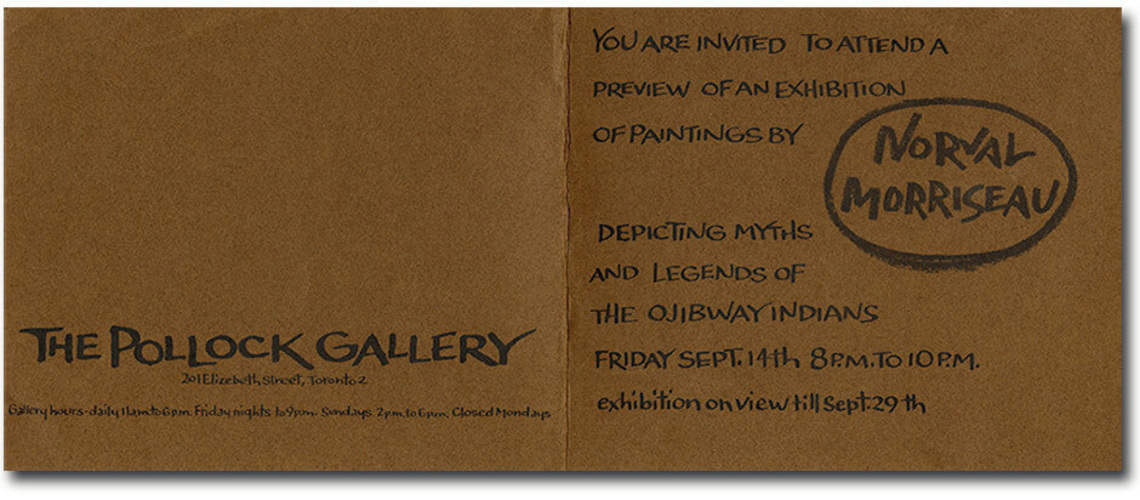

In 1962 an exhibition of the work of Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007) at the Pollock Gallery in Toronto marked the first time an Indigenous artist had shown work in a contemporary art gallery in Canada, and the media hailed the debut as a new development in Canadian art. All the paintings sold on the first day and the exhibition instantly made Morrisseau a celebrity artist and a public figure.

Yet success was a mixed blessing: both Morrisseau’s work and his private life were subjected to scrutiny. His art received mixed reviews, judged by critics as either modern or primitive or a combination of the two, and Morrisseau himself was framed as a painter of legends, in keeping with the images of the “Imaginary Indian,” the “Noble Savage,” and the “Hollywood Indian” peddled by popular culture. This stereotypical attitude was moulded by deeply entrenched colonial views and had little to do with Morrisseau as an individual or an artist. Astutely, Morrisseau defied these conceptions: he attempted to take charge of his life story by challenging interviewers and critics. For example, in the Toronto Star in 1975, he responded to art critic Gary Michael Dault’s query about the media’s scrutiny of his private life: “I am tired of hearing about Norval the drunkard, Norval with the hangover, Norval in jail, Norval torn apart by his allegiance both to Christianity and to the old Indian ways.… They speak about this tortured man, Norval Morrisseau—I’m not tortured. I’ve had a marvelous time. When I was drinking. Now that I’m not drinking. I’ve had a marvelous time in my life.”

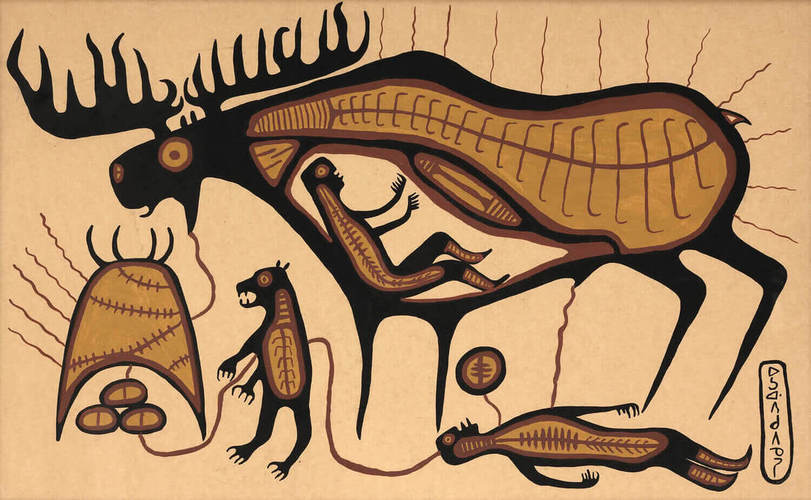

Tempera on brown paper, 81.3 x 132 cm, Glenbow Museum, Calgary. As noted by the Glenbow Museum

Morrisseau recreates the story of a dream of an Ojibwa named Luke Onanakongos (Jo-Go Way): “In dreams of my youth, my spirit dwelled inside a huge moose, and I was protected from hardships of this earth. In middle life, the moose discharged my spirit from his body and it became one with my earthly self. The moose told me to purify myself spiritually and I did this for a time. Finally, in my old age, I rebelled and left forever the dream that pulled me toward that era.”

This effort had mixed results, as press reports typically characterized his challenges as rants. Still, Morrisseau’s paintings began to command attention in art circles, and his success generated interest in the work of other Indigenous artists across Canada. Collectors started to take contemporary Indigenous arts more seriously, and although Morrisseau was still living in Beardmore with his wife Harriet and their growing family, he began to travel to Toronto to sell his works to dealers and to negotiate new commissions.

Morrisseau often relied on art dealers, politicians, and government employees to aid him in his efforts to promote his work. In 1965, the Glenbow Foundation in Calgary purchased eleven Morrisseau works, including Jo-Go Way Moose Dream, c.1964. This significant sale led to more exhibitions, including one at the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) in Quebec City the following year, that signalled a growing national interest in the artist’s work.

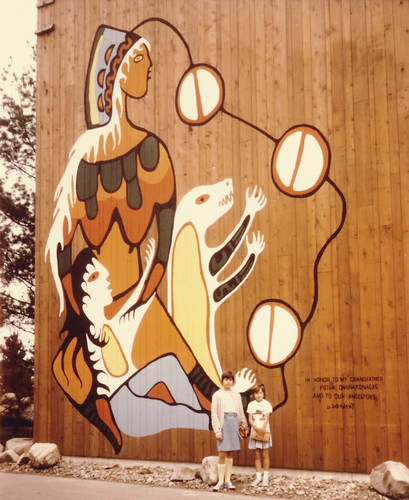

Norval Morrisseau’s mural for the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67. Commissioning Indigenous artists to design the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 is now considered a pivotal step in acknowledging activism around and awareness of Indigenous issues in Canada, but Morrisseau left the project when government officials deemed his mural design of bear cubs nursing from Mother Earth to be too controversial.

Shortly after his exhibition at the Musée du Québec, Morrisseau was one of nine Indigenous artists commissioned to create work for the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal. His large-scale exterior mural showed bear cubs being nursed by Mother Earth, and when organizers raised concerns about this unorthodox image, Morrisseau decided to leave the project rather than censor his drawing. The mural was changed and completed by his friend and fellow artist Carl Ray (1943–1978). Through that commission, however, Morrisseau had met Herbert T. Schwarz, a consultant on the Expo pavilion, an antique dealer, and the owner of Galerie Cartier in Montreal, who would go on to organize Morrisseau’s first international exhibition.

Acrylic on canvas, six panels: each panel 153.5 x 125.7 cm, private collection, on loan to the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

The 1960s established Norval Morrisseau as a noteworthy contemporary Indigenous artist in Canada, and he ended the decade with an international reputation. Based on a solo show held at Galerie Cartier in 1967, a selection of works travelled to the Art Gallery of Newport, in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1968 and then on to Saint Paul Galerie in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the south of France in 1969. The posters advertising the French exhibition declared Morrisseau the “Picasso of the North.” More importantly, by blending the traditional and the contemporary, Morrisseau used his painting to advocate for change, giving voice and artistic direction to new generations of viewers and artists who encounter this art.

This Essay is excerpted from Norval Morrisseau: Life & Work by Carmen Robertson.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans