In 1985 artist, curator, writer, educator, and critic Robert Houle (b. 1947) encountered an installation by German artist Lothar Baumgarten (b. 1944) at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Toronto. It brought the issue of cultural appropriation to the fore. The AGO invited Baumgarten to produce a site-specific work for Walker Court as part of the exhibit The European Iceberg: Creativity in Germany and Italy Today. Baumgarten created Monument for the Native People of Ontario, 1984–85, meant to pay homage to eight nations of the province. Their names were printed in large roman type on the walls surrounding the court at the centre of the AGO.

Site-specific installation at Walker Court, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Houle was jolted by the lack of research in documenting the names. Some were misspelled, and linguistic groups, regions, tribes, and bands were intermingled without distinction. Also disturbing was Baumgarten’s appropriation of the right to document the names. About the installation, Houle writes, “It is a beautiful work, styled as a tribute, but the human drama it presents is unfortunately simply a program of romantic twentieth century anthropology … a transgression of the spiritual integrity of those whose names he has written is to point out that their oral tradition was violated.”

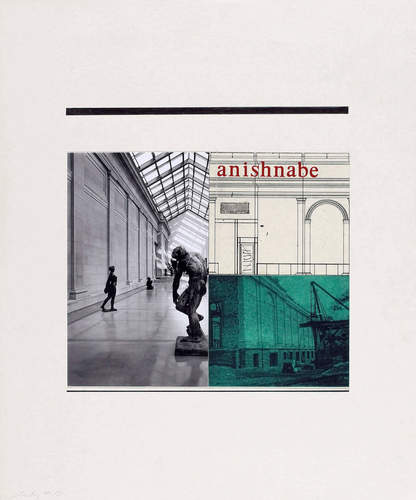

Collage, electrographic prints on wove paper, 43.5 x 35.5 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

When Houle responded to Baumgarten’s installation with Anishnabe Walker Court, 1993, he re-appropriated the German artist’s tribal names, placing them in quotation marks and re-inscribing them in lowercase on the outer wall surrounding Walker Court. Also featuring photographic documentation of the changes to Walker Court over the years, the work comments on the histories of change and memory and how museums such as the AGO, as colonial institutions, are prone to improper memorialization, as in the case of Baumgarten’s installation incorrectly displaying past images and icons of Ontario Native culture.

Gelatin silver print, photocopy, ink on coloured plastic sheet, vinyl self-adhesive letters, black porous point marker, graphite on paper, resin-coated photographic paper, and coloured transparent sheet, 43.2 x 35.7 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Throughout his career Houle has created change in museums and public art galleries, initiating critical discussions about the history and representation of Indigenous peoples. His work has deepened the understanding of cultural appropriation in museums and art galleries, and in a broad spectrum of institutions and disciplines (for example, advertising) invested in maintaining false notions of Western and Indigenous cultures. Cultural appropriation typically refers to a power dynamic in which members of a dominant culture take elements from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed. For Houle, cultural appropriation is about Western culture’s erasing and ignoring of Indigenous voices by misrepresenting its cultures.

Four photo enlargements, site-specific installation at the VIA Rail train station in Winnipeg

Houle frequently selects words from archival documents, implements of war, and consumer goods to highlight how imagery from Indigenous cultures has been exploited for commercial or military enterprise. In the mid-1990s, Houle began to research the commodification of names of famous chiefs and tribes. These Apaches Are Not Helicopters, 1999, for instance, examines the appropriation of Indigenous names as commodities and emblems of war. A site-specific work installed in four half-moon windows at Winnipeg’s VIA Rail train station, the work presented an imaginary homecoming for Chief Geronimo (1829–1909) and his warrior Apaches. Geronimo was famous for resisting colonization and taking a stand against the U.S. government for almost twenty-five years. Houle strategically placed an enlarged archival photograph of Geronimo on the south window of the station, signalling the customary direction of the arrival of Apaches. The final image, on the east window, was of the McDonnell Douglas Apache helicopter.

Four photo enlargements, site-specific installation at the VIA Rail train station in Winnipeg.

Running parallel to an entire history of incorrect cultural projections in paintings, photographs, and written accounts by Europeans in North America is a lack of First Nations’ representation in contemporary culture. Houle writes, “Exclusion from Western representation is deeply rooted in and even protected by a structure that authorizes and legitimizes certain representations while blocking, prohibiting or invalidating others.”

This Essay is excerpted from Robert Houle: Life & Work by Shirley Madill.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans