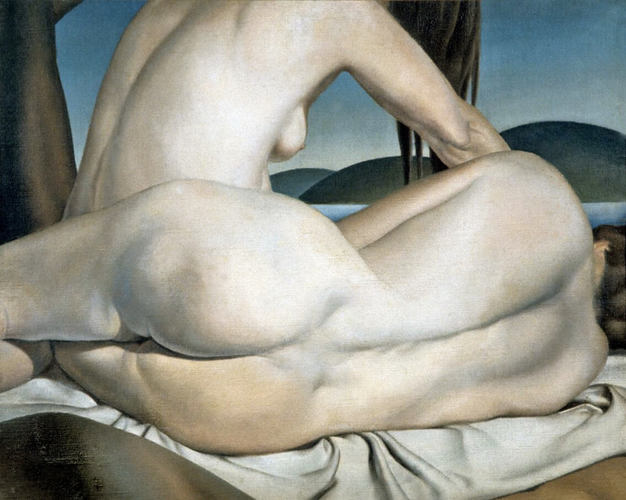

When Figures in a Landscape, 1931, by Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) was accepted for a 1931 exhibition of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), it was not hung. Brooker did not expect to be censored when he submitted the work. A year before, Edwin Holgate (1892–1977) had shown his Nude in a Landscape, c.1930, in the annual exhibition of Ottawa’s National Gallery of Canada without consequence.

Oil on canvas, 60.9 x 76.2 cm, unlocated

Figures in a Landscape had been accepted by the OSA’s exhibition jury and listed in the catalogue. Before the exhibition opened, the local board of education expressed concern that the painting might offend; under the board’s auspices, hundreds of children visited the gallery each week; it was felt the painting’s nude figures might negatively affect their sensibilities. The president of the OSA and the head curator of the gallery asked the jury to withdraw the canvas. When reporters asked why the painting had not been hung, the response was that the gallery was overcrowded. This obvious mendacity led to intense media scrutiny and stories on the front pages of some newspapers.

Edwin Holgate, Nude in a Landscape, c.1930

Oil on canvas, 73.1 x 92.3 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

An indignant Brooker responded with the essay “Nudes and Prudes,” in a collection of essays called Open Door published in 1931 in Ottawa. He argued that the prudery in response to images of the nude arose in large part because elders in society presumed that the young would be corrupted by public displays of nakedness. He hit out against his opponents vigorously: “Nobody pretends . . . that nude paintings or books which deal frankly with sex are dangerous to the morals of grown men and women . . . . In any case . . . the questions of nudity and [lewdness] become ‘questions’ only because of the young.” And the young, he proclaims, become the victims of educators whose eyes are firmly shut to the realms of the imagination. The result is catastrophic because children are made to feel guilt whereas “art is one method of acquainting children with the organs and functions of the body in an atmosphere of candour and beauty.”

Bertram Brooker, Three Figures, 1940

Oil on canvas, 96 x 53.3 cm, Museum London

Despite the fact that the nude is a major, legitimate genre dating back to antiquity, critics made a distinction between representing a nude body and displaying a naked one. Nude, 1933, by Lilias Torrance Newton (1896–1980) was removed from the 1933 Canadian Group of Painters exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto in part, as the critic Donald Buchanan put it, because the model was “a naked lady, not a nude, for she wore green slippers.” For Canadian painters, this issue sometimes had a nationalist bias. When Sleeping Woman, c.1929, by Randolph Hewton (1888–1960) was shown in 1930, as Michèle Grandbois points out, “A.Y. Jackson confessed at the time to being troubled by the disparity between this work and what was expected of a true Canadian form of expression, best embodied in the landscape genre. So, even as Canadian art was asserting its modernity, it refused to identify with the nude.”

Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 53.3 cm, Collection of Lynn and Ken Martens

For Brooker, the nude was a genre that fully liberated his imagination. He could allow his models to block a view, as in Figures in a Landscape, render them in precise, clinical ways, as in Torso, 1937, or place them in a classical context with a playful edge, as in Pygmalion’s Miracle, 1949. As Anna Hudson has pointed out, he could in Seated Figure, 1935, create a monumental studio nude “whose humanity is profoundly felt in the fleshiness of the model’s abdomen. . . . This ordinary woman is the object of extraordinary intimacy, which in life is fleeting and in art enduring.”

Oil on canvas, 101.6 x 101.6 cm, Art Gallery of Hamilton

This Essay is excerpted from Bertram Brooker: Life & Work by James King.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans