While best known as a sculptor, Canadian artist Sorel Etrog (1933–2014) expressed his hunger for innovation through other creative work as well. From the late 1960s onward he forged friendships with prominent intellectual and artistic figures such as the playwrights Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) and Eugène Ionesco (1909–1994), media theorist Marshall McLuhan (1911–1980), and the American composer John Cage (1912–1992), with whom he collaborated on many projects. Etrog co-produced artist books, stage and set designs, and multimedia performances, diverse artistic experiments that exemplify the artist’s inventiveness, curiosity, and creative versatility.

Sorel Etrog, Bird that Does Not Exist II, 1965

Bronze, 22.9 x 45.7 cm, The Estate of Sorel Etrog

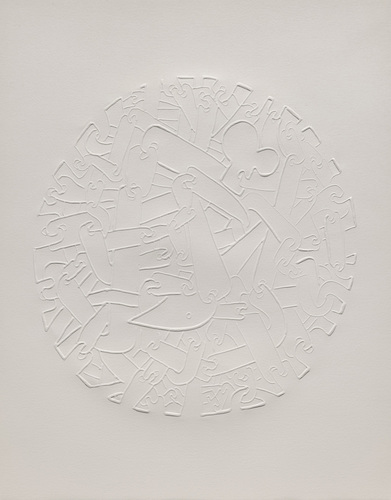

Etrog’s earliest collaboration was with the French poet Claude Aveline (1901–1992). The artist first created sculptures inspired by Aveline’s poem “Portrait de l’Oiseau-Qui-N’Existe-Pas” (Portrait of the bird that does not exist) for the Canadian pavilion at the 1966 Venice Biennale, after which he approached Aveline with an offer to illustrate the same poem in a book. This idea materialized in a 1967 artist book titled L’oiseau qui n’existe pas, which reveals the ability of Etrog—himself a writer and poet—to translate words into a distinct visual world, giving the text a new meaning. Combining literature and visual art became a regular practice for Etrog, who designed and illustrated six artist books in collaboration with important writers, including the 1969 Chocs with Ionesco, developed from a poem by the playwright.

Sorel Etrog, Bird that Does Not Exist, 1967

Engraving, 40.8 cm x 31.8 cm, from the artist’s book L’oiseau qui n’existe pas (The Bird that Does Not Exist), with poem by Claude Aveline, The Estate of Sorel Etrog

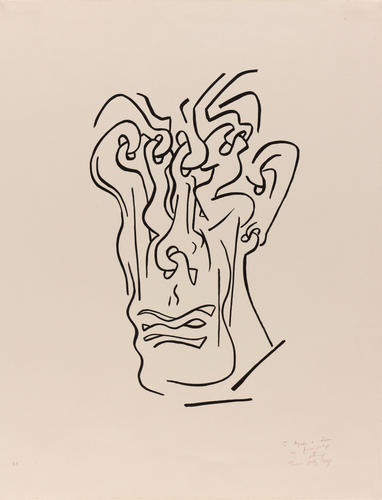

The most meaningful of his friendships-turned-collaborations was the one Etrog forged with Samuel Beckett, the author of the play Waiting for Godot, among many other works. When the two met in the U.K. in 1969, at a function for a project whose funds were donated by Etrog’s Canadian patron, Samuel J. Zacks (1904–1970), Etrog was in his mid-thirties and Beckett in his early sixties; they quickly connected and stayed friends until Beckett’s death in 1989. Etrog later recalled that during that first meeting he immediately began to sketch the writer’s portrait: “Surprisingly I found myself making drawings of Beckett’s head which has still haunted me ever since meeting him. I am not too much of a portraitist, and I would rather say that I tried to capture the inner tension of our meeting. (His? Mine? Or both? I don’t know).”

Sorel Etrog, Beckett, 1969

Lithograph on paper, sheet: 66 x 50.8 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Etrog soon began working on illustrations for Beckett’s short prose text “Imagination Dead Imagine” (1965). The project was not published until 1982, when the Scottish-Canadian writer and publisher John Calder (1927–2018) released a book in a limited edition. The art critic John Bentley Mays (1941–2016) praised Etrog for his ability to “read a modernist text of such intricacy and density as Beckett’s, understand it and—instead of merely illustrating it—re-situate the words in an imaginative visual space which creates, in effect, a new book, with new and emerging meaning.”

Page from Imagination Dead Imagine, 1982

Limited-edition artist book designed and illustrated by Sorel Etrog with text by Samuel Beckett, The Estate of Sorel Etrog

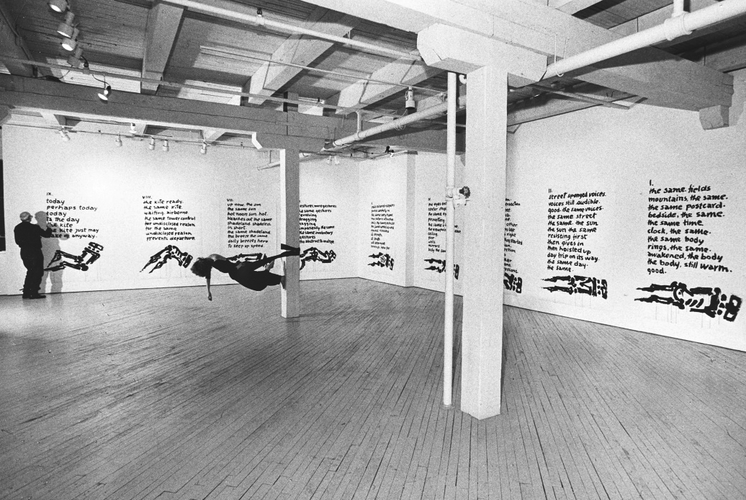

Etrog’s groundbreaking work The Bodifestation of the Kite, 1984, was made in celebration of Beckett’s seventy-eighth birthday. In this performance piece, Etrog inscribed and illustrated his own poem “The Kite” “live” on the walls of Toronto’s Grunwald Gallery, while Gloria Luoma of the National Ballet of Canada danced Etrog’s choreography to electronic music that the artist had composed. Among the approximately 150 people who attended the single performance was the art historian Joyce Zemans, who wrote that it was a “moving artwork and a fitting tribute to Samuel Beckett.”

Sorel Etrog, The Bodifestation of the Kite (installation view at Grunwald Gallery, Toronto), 1984

Various media including drawing, dance, and music, performance with Gloria Luoma at Grunwald Gallery, Toronto

Although these collaborations are lesser known than Etrog’s sculptures, their importance lies in how they reveal the extraordinary scope of the artist’s talent, creativity, and originality. With them in mind, the large bronze sculptural work for which Etrog is internationally renowned can be understood in the larger context of his ongoing commitment to and hunger for experimentation and innovation.

This Essay is excerpted from Sorel Etrog: Life & Work by Alma Mikulinsky.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix