In 1926, Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) left England to take up the position of head of design at the recently established Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (now the Emily Carr University of Art + Design). He arrived in Vancouver in September of that year—and for the rest of his life he would teach as well as paint.

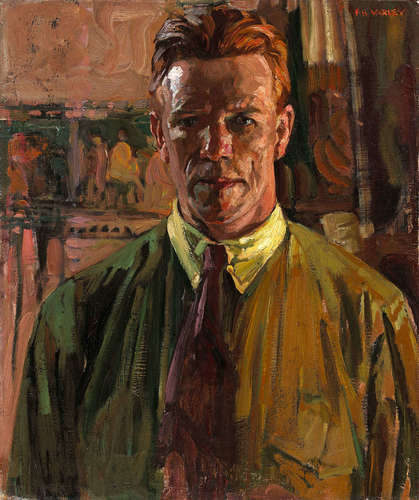

F.H. Varley, Self-portrait, 1919

Oil on canvas, 60.5 x 51 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

The late 1920s was an exciting time in Vancouver—a dramatic change from the staid Victorian art scene that had discouraged Emily Carr (1871–1945) in 1913 when she abandoned painting for over a decade. The creation of the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (VSDAA) was central to the shift, as was the arrival in the city of two men: Fred Varley (1881–1969), the renowned Group of Seven landscape and portrait painter who was the first head of drawing, painting, and composition at the school; and John Vanderpant (1884–1939), an internationally recognized photographer. Both were to have a profound influence on Macdonald.

F.H. Varley, Portrait of John Vanderpant, c.1930

Oil on plywood, 35.5 x 45.7 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery. Close friends, Varley and Vanderpant often travelled in Vanderpant’s car, exploring the mountain landscape and drawing and photographing together.

Varley fell in love with the British Columbia landscape and organized sketching trips for his colleagues and students. Although he had previously directed his artistic attention towards design work, Macdonald began to focus on painting and shared a studio with Varley, who became his mentor. Recognizing that the grandeur of the landscape required a stronger medium than the watercolour and tempera of his earlier work, Macdonald began to paint in oil, creating works including Lytton Church, B.C., 1930. The powerful connection he made with the rugged B.C. scenery, his spiritual identification with nature, and his determination to capture the experience of the landscape in paint set him on the quest that would shape his painting for the rest of his life.

Jock Macdonald, Lytton Church, B.C., 1930

Oil on canvas, 61.2 x 71.5 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

In 1926 Vanderpant and Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970) opened the Vanderpant Galleries, which exhibited contemporary art and photography and promoted B.C. artists. The gallery soon became a force for modernist art in Vancouver and, between 1928 and 1939, a gathering place for the city’s intellectual and artistic communities.

Although Vancouver remained a conservative city culturally, an increasing number of residents were attracted to new ideas, and particularly to Eastern thought and spiritual concepts. In April 1929 a crowd filled the Vancouver Theatre to capacity, and thousands more stood in line to hear the poet-philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, who “carried the audience into the realm of pure aesthetics.” For the artistic community, the Vancouver scene in the late 1920s and early 1930s might be summed up in Fred Varley’s advice to his students to “forget anything not mystical.” In 1932 Macdonald painted In the White Forest—an image that represents a distinct shift in his work and the beginning of his lifelong search for the spiritual aspect of nature in art.

Jock Macdonald, In the White Forest, 1932

Oil on canvas, 66 x 76.2 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

These heady days were not to last. With the onslaught of the Depression, the VSDAA cut faculty salaries drastically. When Macdonald and Varley realized that the burden was not shared fairly, they were outraged and in early 1933 resigned in protest.

This Essay is excerpted from Jock Macdonald: Life & Work by Joyce Zemans.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans