Before I visited Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers at the Campbell River Art Gallery, she shared with me photographs and audio clips to introduce the exhibit. I was immediately struck by how the material resonated with me; it was familial and familiar, yet “foreign.” In her art, Tam challenges viewers to think differently. In this instance, a time when one outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the rise of anti-Asian racism, she exposes the lie that violence is somehow recent (“it’s not who we are as Canadians”) by juxtaposing past and present. Though there are global aspects to this exhibit, its gaze is directed to Canada, British Columbia, and Vancouver Island.

Familial/Familiar/Foreign

C.S. Wing Studio, 2020, is an installation that honours a maker of portraits, and it is a reminder of the familiar, the photograph. In recreating the studio tableau, it is also foreign to those accustomed to snapping images on a smartphone. Phones as cameras make the act of photography an everyday occurrence, yet a hundred-plus years ago, to have a photograph taken was a much more purposeful act. Who in society owned a camera then?

Mixed media, 304.8 x 294.7 x 167.6 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Hugues Charbonneau, Montreal. Installation view of C.S. Wing Studio at the Koffler Centre of the Arts, Toronto, 2020. Photo credit: Karen Tam.

As a photographer, what distinguished C.S. (Chow Shong) Wing was his Chinese ancestry; he was born in Quesnel—not Vancouver, not Victoria. He was home-grown—a B.C. boy! His family’s presence in the interior of B.C. is a reminder that Chinatowns existed throughout B.C. and beyond, where early Chinese immigrants and Chinese Canadians contributed to their respective communities economically and socially. Besides the occasional studio, there were other “Chinese” businesses, such as general stores, laundries, and restaurants/cafés, and even social organizations.

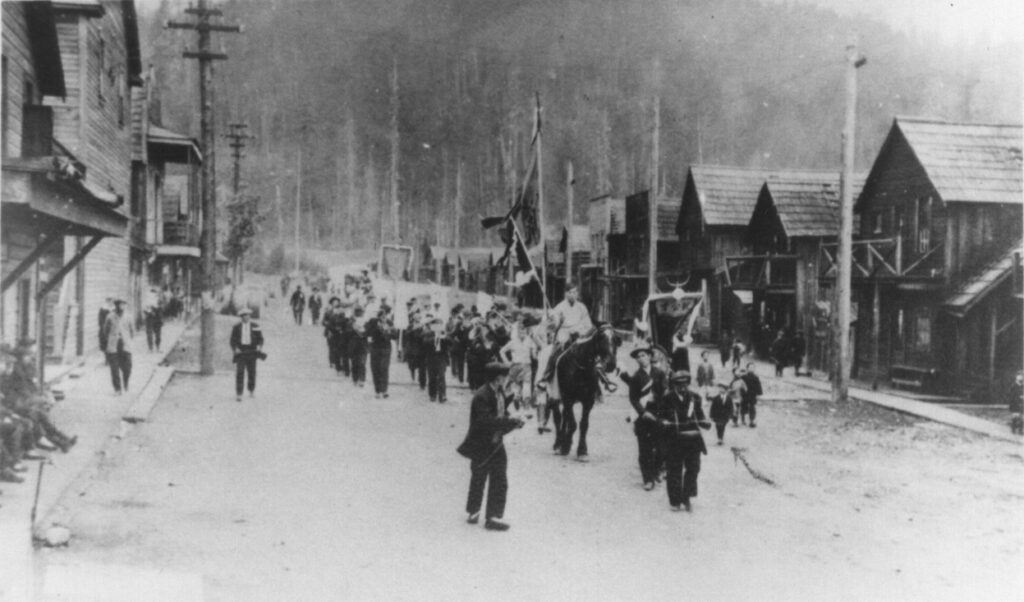

A further reminder of this Canadian story are the photographs of individuals and events from two Vancouver Island Chinatowns: Cumberland and Nanaimo. With the prominence of Vancouver’s Chinese Canadian community, there is a tendency to “forget” the places where few lo wah kiu (“old overseas Chinese”) continue to live. In such instances, erasure happens. This familiar object, the photograph, makes visible everyday lives and events.

Black and white print, Collection of the Cumberland Museum and Archives.

Tam includes more than one photograph of an “unidentified Chinese man,” such as Unidentified Chinese Man Lighting a Cigarette, pre-1929. Individuals like this man, even if “unidentified,” are someone’s relative or friend. A chance encounter with an image and a viewer may be able to reveal, in part, a story or an identity. The unknowable becomes knowable. For me, this image recalls an experience with Cumberland photographs taken by the Hayashi Studio, seen in the exhibition Shashin: Japanese Canadian Studio Photography to 1942 (University of Victoria Legacy Art Galleries, 2005). Among the pictures, I found one of two men, identified only as being from the Japanese Canadian community. To my surprise, the seated figure was my Uncle Kelly, who arrived in B.C. from China in 1910.

Black and white print, Collection of the Cumberland Museum and Archives.

This led to the identification of Uncle Kelly in another photograph—now correctly noted and included among Cumberland Museum and Archives’ “Chinatown” photo album!

Black and white print, Collection of the Cumberland Museum and Archives.

The familiar was familial, as was my viewing of a selected photograph in Autumn Tigers. Tam included “Chinese Funeral Procession on Streets of Chinatown, Cumberland B.C.,” and someone had marked the image with an arrow, directing my gaze to a child with a cap walking alongside the procession. That child—he was my Uncle Harold. Once more, my history as a Canadian is found within these objects, which is likely true for others who identify as descendants of the lo wah kiu.

Photographer unknown, Collection of the Cumberland Museum and Archives.

For marginalized peoples who faced the racist policies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from head tax to out-right exclusionary laws, early photographers’ works provide contemporary society with evidence of long-established communities. In effect they announce: “we exist.” “We are as home-grown Canadian” as those who are simply identified as “People” or white society in the digital photo albums of the Cumberland Museum and Archives. Among the many albums, seven are labelled “People,” while there are separate ones for First Nations, African Canadian, Japanese, and Chinese. The latter labelling reinforces the “other” by their separate physical locations.

Yet in 2020 and 2021, angry voices are heard shouting, “Go back to where you come from,” “You don’t belong here,” or “F***ING CH**K!!” to those who appear to be of Asian descent, without the speakers knowing the ancestral origins of their intended target(s). As well, objects associated with Chinese heritage have been defaced and attacked. The attention is directed primarily at “Chinese” due to conflating disease (COVID-19) and country (People’s Republic of China). Thus, even in Canadian media, “China Virus” was flashed across headlines.

Screen-printed satin wallpaper, repositionable printed wallpaper, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Hugues Charbonneau, Montreal. Photo credit: Karen Tam.

Tam’s artistry brings awareness of the violence directed at people of Asian descent globally and in former Chinatowns or communities in Ruinscape, 2020. Look closely at the images of people and places: they are under attack. If you are a student of Chinese Canadian history, the places illustrated may be familiar; however, to many they are foreign or unknown. One such place is D’Arcy Island; as part of the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve, it is a popular kayaking or boating destination. Yet its history, specifically, as a leper colony for the Chinese is not to be found on the Parks Canada website.

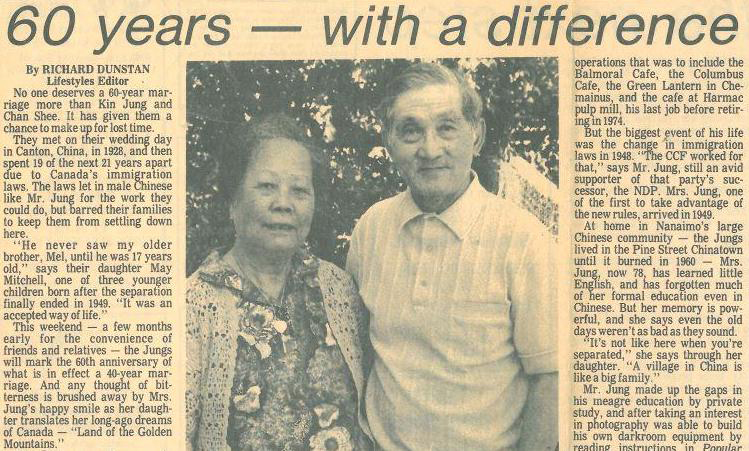

Tam responded to the rise in anti-Asian violence with art, in part, by creating banners, harkening to those used in the past as illustrated in her choice of accompanying photographs such as “Celebration in Nanaimo’s Chinatown.” In her re/creations, words express endurance and resilience, as can be seen in Refuse to eat our bitterness, 2021, and the chrysanthemum has opened twelve times (Banner), 2020. The audio element of the Autumn Tigers exhibition reinforced the personal impact of immigration under exclusionary policies. Visitors heard an excerpt of the song the chrysanthemum has opened twelve times (Audio), 2020, emphasizing the personal ordeal of a letter writer expressing the same words found in the banner. Though my understanding of any Chinese dialect is minimal, I recognized the intonations of Cantonese opera, as well as the tonal qualities of Toishanese (the dialect spoken by many early Chinese immigrants to Canada). Song and music were familiar and foreign at the same time; nevertheless, I heard sounds of longing.

In the past, forced separation was a reality for many—that is bitterness. With the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923, husbands were in Canada while wives, and sometimes children, remained in China. The words “the chrysanthemum has opened twelve times” remind the viewer of that absence through the passage of time; in this case, the yearly flowering of chrysanthemum. Only on the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1947 did the process of family reunification begin. In some cases, there was none. I was reminded of this when I met my cousin (dai-je, older sister) in China in 2016; she had never met her father, my Uncle Kelly. Much bitterness has been eaten.

“Eating bitterness” is an expression (and “virtue”) of Chinese character to mean “to persevere through hardship without complaint.” In Refuse to eat our bitterness, Tam commands us: refuse—react, do not accept this abuse! To “refuse” is her rally call to those within the Asian Canadian community. Why do I say this? With one word, “our,” we are made to claim it—to break the myth of the model minority. We are neither docile nor quiet; we stand in solidarity against the hate. We stand against the violence.

In juxtaposing past and present in Autumn Tigers, Karen Tam directs the gaze of the viewer to see what has always been there—invisible yet visible—simply for not really seeing.

For more works by Karen Tam visit the online exhibition.

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix