As one of the first artists to make drawings for the print studio in Cape Dorset in the early 1960s, Pitseolak Ashoona (c.1905–1983) had no instructors and few examples of artwork on paper to follow. Promotional booklets such as Canadian Eskimo Art by James Houston (1921–2005), published in 1964 by the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources, indicated which types of art sold well in the market, but there was little or no information on techniques or pictorial devices. Visiting artists offered some training in specific media—such as Alexander Wyse (b. 1938) introducing engraving in Cape Dorset in the early 1960s, and K.M. Graham (1913–2008) encouraging artists to explore the use of acrylics in the late 1970s—but rarely did Inuit of Pitseolak’s generation have the opportunity to study art techniques or methods. Instead, Pitseolak worked out solutions to artistic problems—such as how to convey the movement of figures or place them within a landscape—through what can be described as a self-directed program of repetitious drawings. “Does it take much planning to draw? Ahalona! It takes much thinking, and I think it is hard to think. It is hard like housework,” she said.

Inuit artists of the Cape Dorset co-operative, 1961. From left, top row: Napachie Pootoogook, Pudlo Pudlat; bottom row: Egevadluq Ragee, Kenojuak Ashevak, Lucy Qinnuayuak, Pitseolak Ashoona, Kiakshuk, Parr. Photograph by B. Korda.

For centuries leading up to and including Pitseolak’s own lifetime, Inuit made and perfected everything they needed for survival—from tools to sleds to shelter—through invention and adaptation of the material resources at hand. This required innovation through trial and error, through a process of learning by experimenting and hands-on practice. Inuit artists of Pitseolak’s generation had a similar approach to their artmaking; they proved to be resourceful, experimenting to find solutions that worked—though the process was complicated by there being no measurable, physical function with art. The ingrained experimental approach allowed them to excel in diverse media. Each artist had to invent his or her own style to convey ideas, which is reflected in the wide stylistic range and the directness of expression that typifies Inuit art.

Unlike many Inuit artists who work solely within a style established early in their careers, Pitseolak followed a process of continuous experimentation, from early roughed-out drawings with an emphasis on line, to flamboyant well-composed scenes in rich colour, to the more subdued and refined quality of her last works.

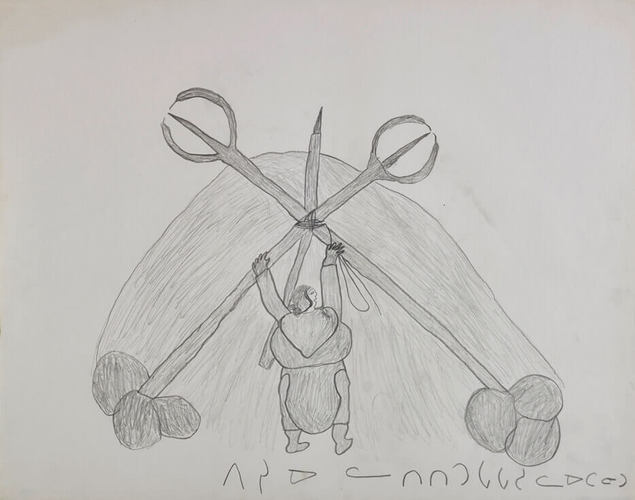

Pitseolak Ashoona, Untitled, c.1959–65

Graphite on paper, 47.9 x 60.7 cm, collection of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative Ltd., on loan to the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario. In this humorous drawing, a woman uses gigantic kakivak (fish spears) as tent poles.

Pitseolak taught herself to draw figures, both human and animal. Series of her drawings made during the 1960s show how she learned to capture accurate proportions and movement so that her figures appear naturalistic. Even in her later drawings she makes no attempt at modelling or shading—techniques used to create the illusion of three-dimensional form—and yet her figures appear to have bulk and substance.

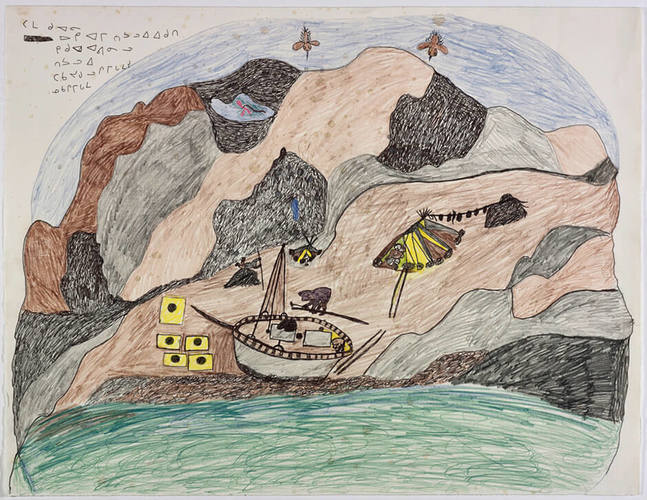

Pitseolak Ashoona, Untitled, 1981

Coloured pencil and coloured felt-tip pen on paper, 51.2 x 66.8 cm, collection of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative Ltd., on loan to the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario. This is one of several drawings of ships, most likely based on the schooner Bowdoin, that Pitseolak completed near the end of her life.

Working largely outside of Western art traditions, Inuit artists were categorized as “naive” or “primitive” in their style and approaches to making art, as in a 1969 description of Cape Dorset drawings as “childlike drawings in nursery colours . . . like innocent documentary.” Countering such clichés, Pitseolak’s self-directed efforts toward developing her visual expression were consistent with those of an artist with formal arts training and brought recognition to the validity of Inuit systems of learning.

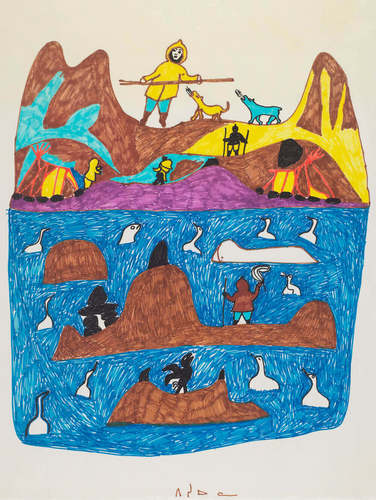

Pitseolak Ashoona, Summer Voyage, 1971

Coloured felt-tip pen on paper, 68.6 x 53.2 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Drawing on her memories of living on the land, Pitseolak made many images of the landscape, continuously refining her depiction of visual space. From her years of designing and sewing textiles, she adapted two devices found in Inuit clothing design—mirroring a motif, and breaking down the visual surface into registers. Part of the first generation to create modern Inuit art, Pitseolak used her work to find new ways to transmit Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, the knowledge and values passed down through generations as “things we have always known, things crucial to our survival.”

This Essay is excerpted from Pitseolak Ashoona: Life & Work by Christine Lalonde.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans