Kent Monkman is a visual storyteller. For more than two decades he has subverted art history’s established canon through the appropriation of works that tell stories of European domination and the obliteration of North American Indigenous cultures. Monkman challenges the accuracy of such representations by repopulating and correcting settler landscapes in a transgressive manner. He reimagines well-known paintings in order to provide a contemporary, critical point of view—and often his agent of disruption and change is one Miss Chief Eagle Testickle (originally called Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle), or Miss Chief for short.

Revision and Resistance: mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, published by the Art Canada Institute, is now available for purchase. Click here to order your copy.

Miss Chief ’s name is a play on the words “mischief ” and “egotistical,” and in its early use also incorporated “Cher” as a way to perform a reimagining of the 1970s pop diva.[1] Today, she is known as Monkman’s alter ego, living and taking part in art history. In the tradition of Indigenous storytelling, she embodies the mythological trickster and takes the form of a two-spirit, third gender, supernatural character who exhibits a great degree of intellect and knowledge when she is present in a work of art. Monkman uses her to help guide viewers to see new truths. Glamorous, flamboyant, confident, and always high-heeled, she inhabits paintings and appears in installations, performances, and videos. Since her first manifestation nearly twenty years ago, she’s played a central role in correcting accounts of Indigenous histories. Indeed, Miss Chief is the key to much of the artist’s work.

Monkman’s own story begins in Manitoba. A member of the Fisher River First Nation, he was born in 1965—one of four children—in a small hospital in St. Mary’s, Ontario, his Anglo-Canadian mother’s hometown. Soon after, the family returned to northern Manitoba and the Cree community of Shamattawa where his parents were engaged in missionary work. His father then moved the family to Winnipeg and settled in the middle-class neighbourhood of River Heights. Monkman’s great-grandmother, who lived with the family until he was ten, spoke only Cree. Most of the city’s Indigenous population was located in the economically challenged North End. From an early age, Monkman discovered that Winnipeg was riven by race and class. While identifying with both sides of his heritage, he developed a stronger connection with his Cree culture thanks to the presence of his father’s relatives, especially his great-grandmother.

Right: Clarence Tillenius, Bison Diorama (detail)

Taxidermy and mixed media, 8.7 m (width) × 7.5 m (depth), Orientation Gallery, Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg

Monkman remembers seeing the dioramas in the Manitoba Museum, then called the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, during school field trips. These theatrical tableaux represented Indigenous people as if frozen in time, often hunting bison or camping in prairie landscapes. This dramatic dislocation between that ideal and the catastrophic fall out of colonization evident outside the museum, where Indigenous people were living on the streets, was a fundamental turning point in the artist’s thinking. In his words, the museum visits “were inspirational and scarring at the same time.”[2] In the fall of 1983, shortly after graduating high school, Monkman began studying illustration through a commercial art program at Sheridan College in Oakville, Ontario. After completing his degree in 1986, he became involved in theatre and set design at Native Earth Performing Arts in Toronto.

Although known for his representational paintings, Monkman’s practice was initially semi-abstract. An early body of work, titled The Prayer Language, consisted of acrylic paintings in which he incorporated Cree syllabics drawn from his parents’ hymn book, which appear embedded in the paint. Beneath them, ghost-like homoerotic images of men wrestling emerge. The Cree translations of Christian hymns became a backdrop to define a personal history that investigated questions of sexuality and power, referencing the complex history of Indigenous and European contact. At the time Monkman spoke very little Cree and had only basic reading knowledge; as a result, he saw the language itself as an abstraction.

Right: Kent Monkman, Superior, 2001

Watercolour on paper, 36 × 26 cm

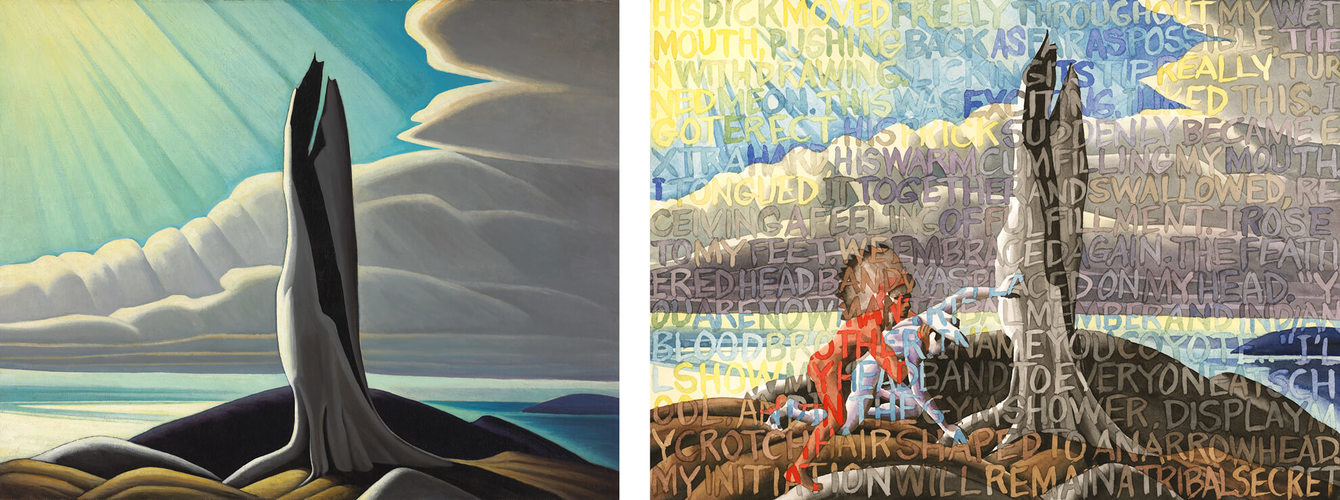

Finding this work “too personal and cryptic,” Monkman then turned to representational painting, a more effective method of communication because of its accessibility. His first targets were the heroic landscapes of the revered early twentieth-century Canadian painters the Group of Seven. He focused his attention on iconic works such as North Shore, Lake Superior, 1926, by Lawren Harris. While quoting these paintings, Monkman inserted images of couplings between submissive cowboys and dominant young “Indians,” overlaying them with racist text culled from pulp westerns or explicit text from gay erotic fiction, using sexual power dynamics as a means of exploring larger issues of Christianity and colonialism. Afterward, Monkman abandoned text entirely and shifted his focus to landscapes in which figures from frontier mythology—cowboys and “Indians” again, and also trappers, pioneers, missionaries, and explorers—interacted in scenes that varied from trading and fighting to sexual antics.

In early 2000, Monkman embarked on a series of inspired acrylic recreations of canonical nineteenth-century European representations of Indigenous peoples and the North American West. He took on paintings by Paul Kane, John Mix Stanley, and Albert Bierstadt with equal stylistic mastery but revisionist intent, inserting subversive content that exposed the inherent racism of the originals. In works such as Daniel Boone’s First View of the Kentucky Valley, 2001, Monkman placed miniature homoerotic scenes within large-scale landscapes resembling stereotypical images of the western plains of the 1880s.

Monkman soon reached the point where he desired a figure “who could live inside his work and look at the Europeans.”[3] Miss Chief was born. He drew inspiration for the character from the painting Dance to the Berdash, 1835–37, by American artist George Catlin, in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. The work depicts a group of men, including one dressed in women’s clothing, performing a ceremonial dance to celebrate a Sac and Fox “Berdash”, or two-spirit person who has both masculine and feminine traits. Catlin described the dance as “one of the most unaccountable and disgusting customs that I have ever met… [and] I should wish that it might be extinguished before it be more fully recorded.”[4] The image, combined with Catlin’s disparaging and racist remarks, prompted Monkman to incorporate a persona in his paintings who would embrace gender and sexuality, honouring the tradition of the two-spirit in Indigenous societies as a response to Europeans who did not understand sexual fluidity. For Monkman, Miss Chief encompasses an aspect of the Cree worldview and a larger Indigenous notion of the sacred where everyone and everything is valued.

of Canada, Ottawa

In 2002, Miss Chief made her first appearance in the painting Portrait of the Artist as Hunter. In it, a buffalo hunt plays out across the backdrop of a prairie landscape with nearly naked Indigenous riders on horseback racing into a herd of buffalo. Where artists such as Stanley or Catlin would have portrayed such a scene with a lament for the past, Monkman reverses it by inserting two additional figures: a cowboy on horseback (naked except for chaps), and another, who pursues him, in a pink headdress, fluttering loincloth, and stiletto heels: the diva warrior, Miss Chief.[5] She makes a second appearance in Study for Artist and Model, 2003, a work that can be considered a self-portrait. Two male figures are modelled against a background similar to Kane’s painterly renditions of forests. The artist in the painting is Miss Chief, posed with her back to the viewer. She is seen standing in front of a tipi-style artist’s easel, bow and arrow in one hand and paintbrush in the other. She paints a glyph of her model on a piece of birch bark. The model is a cowboy, naked except for his Stetson hat and boots, tied to a tree and pierced by arrows. His stance echoes that of Saint Sebastian, a popular Renaissance martyr. This is the only painting by Monkman signed S.E.T.—Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle’s initials. From this point on Monkman’s identity is subsumed into hers, and the relationship between artist and subject becomes ambiguous and ever changing.[6]

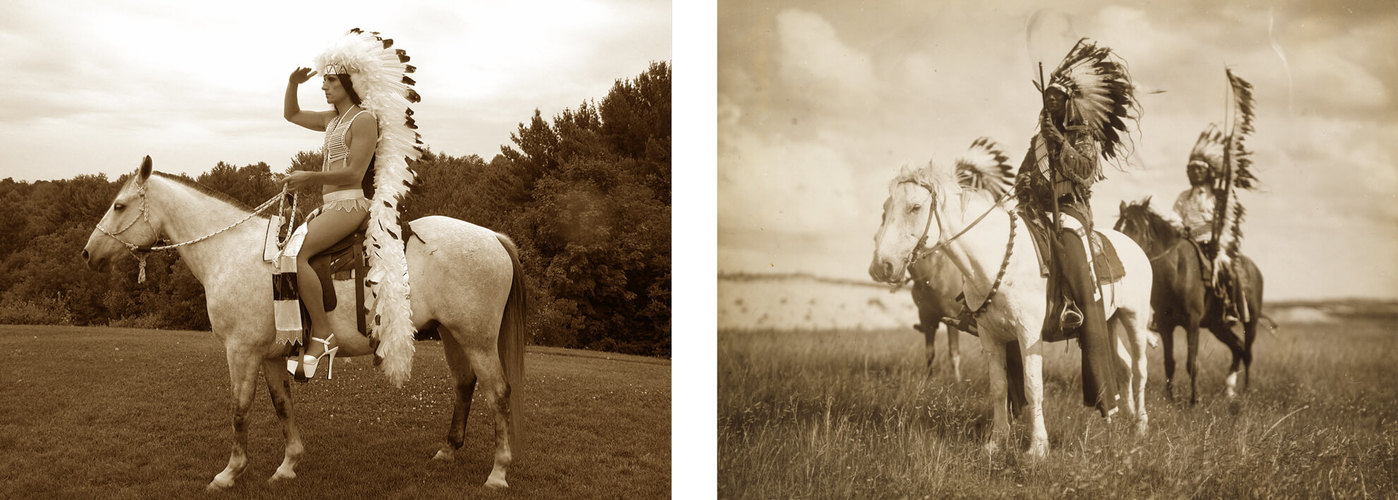

In 2004, Miss Chief made her first physical appearance in a performance at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, which is documented in Monkman’s video artwork, Group of Seven Inches, 2005, made with his longtime collaborator Gisèle Gordon. After touring the collection, known for its conservative approach to Canadian art due to its association with the Group of Seven, and viewing a film by the American photographer Edward Curtis, long considered a voice of authority because of his photographs of Indigenous peoples, Monkman unleashed Miss Chief. He documented the intervention in a video that shows his alter-ego fashionably dressed in a lush and lengthy feathered headdress, seven-inch pink stacked heels, a flowing diaphanous breechcloth, and false eyelashes. She rides a white horse down the road that leads into the grounds of the McMichael. While on her way she encounters two white males dressed in moccasins and breechcloths. She takes them to Tom Thomson’s shack, feeds them liquor, and then spanks them with snowshoes, canoe paddles, and a cast-iron frying pan. Afterward, she dresses them in the late eighteenth century European garb of powdered wigs and ruffled shirts and sets out to paint their portraits. As a response to artists like Catlin and photographers like Curtis that nonetheless mirrors their ambitions in reverse, she states: “I have determined to devote whatever talents and proficiency I possess to the painting of a series of pictures illustrative of the European male. The subject is one in which I have felt a deep interest since childhood having become intimately familiar in my native land with the hundreds of trappers, voyageurs, priests, and farmers who represent the noblest races of Europe…”[7]

Right: Edward S. Curtis, Sioux Chiefs, c.1905

Photographic print, 15.1 × 20.2 cm, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Henceforth, Miss Chief began to speak for herself, narrating an imagined autobiographical account of a time-travelling past, present, and future. In an early interview with Michif curator and art historian Cathy Mattes, she shared a story about Catlin and how he recruited her to travel with him: “He took me away, quite forcibly, I might add, over to Europe. I became a performer in Catlin’s travelling gallery, and we toured all over Europe. It was during that experience that I learned many things about the European male. I decided it was time to turn the tables and be the artist, not the model. Besides, Catlin threw me out on the street and I wandered Europe.”[8] Monkman’s interest in challenging the accounts of Indigenous histories as told by colonizers is fully realized through Miss Chief. She reverses the gaze of the colonizers by proposing an equally false history, one full of assumption, mischaracterization, and fetishization.

In The Emergence of a Legend, 2006, Monkman imagines Miss Chief as a performer in Catlin’s Indian Gallery. The series of five chromogenic prints, produced in collaboration with photographer Chris Chapman, are studio portraits that emulate antique daguerreotypes, in which Miss Chief is portrayed in various guises. These photos trace the history of Indigenous performance in European culture. Miss Chief is Hunter, Vaudeville Star, Cindy Silverscreen, Film Director, and Trapper’s Bride, challenging history by playing the starring role. Through this reimagining, she subverts stereotypical images of Indigenous peoples from the nineteenth century, questioning the work, motivations, and egos of Catlin and Curtis.

Once Miss Chief was brought to life, Monkman discovered that she could become an important voice to express Indigenous issues. In his words, “You can say and create art in performance language that you can’t in a painting, so it’s really expanded my abilities to communicate with people.”[9] In 2007, Miss Chief appeared in Séance, in which she communicated with the spirits of Kane, Catlin, and painter Eugène Delacroix as part of the Shapeshifters: Time Travellers and Storytellers exhibition held at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. The performance was a response to one of Monkman’s paintings being excluded from the museum’s First People’s Gallery out of fear his work would challenge the historical legitimacy of paintings by Kane.

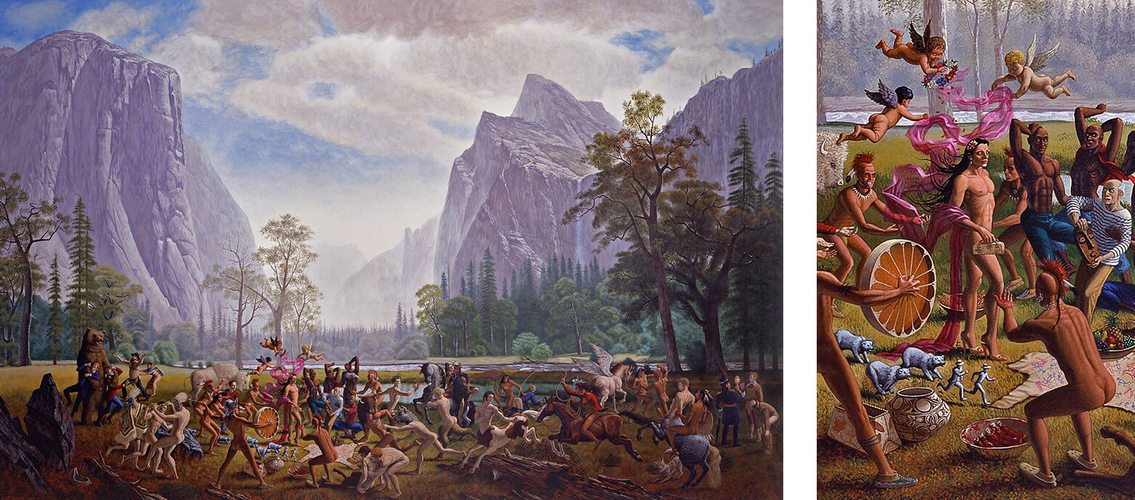

Miss Chief was fast becoming an important figure in Canadian history with the power to undermine important institutional collections of art. Her new-found status was celebrated in Monkman’s first major touring solo exhibition, The Triumph of Mischief, which travelled to various galleries and museums across Canada from 2007 to 2010. During the tour, Monkman continued to research historical works of art as a means of challenging Canada’s early history and included his findings. This allowed for an unprecedented adaptability: Monkman could exhibit new work based on local histories and contexts drawn directly from each collection. The title piece for the exhibition is The Triumph of Mischief, 2007, now a key work in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. The painting’s background resembles Yosemite Valley and echoes the sublime romanticist landscape paintings of the German-American Albert Bierstadt. The scene is conceptually similar to Catlin’s Dance to the Berdash, only in Monkman’s interpretation there is a subversive twist. The painting is sexually charged and contains images of artists, trappers, explorers, and mythical characters engaged in a wild scene of homoerotic violence and debauchery. All revelry is orchestrated around the central character, Miss Chief, who now appears as a time-travelling intervener in the colonial past and present.

For the Winnipeg Art Gallery version of The Triumph of Mischief, held in 2008, Monkman gathered inspiration from three historical works in the permanent collection: Femmes de Caughnawaga, 1924, a bronze by Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté; The Dakota Boat, c.1880, a painting by W. Frank Lynn; and A Metis Family (A Halfcast with His Wife and Child), c.1825, a watercolour by Peter Rindisbacher. Visual quotations from these works are found in Monkman’s painting Woe to Those Who Remember from Whence They Came, 2008. In the painting’s far left, a prairie vista overlooking historic Fort Garry sets the stage. A former Hudson’s Bay trading post, this is the site where Treaty No. 1 was signed between the Ojibway and Swampy Cree of Manitoba and the Crown. The same paddleboat in Lynn’s painting that symbolizes technological progress is seen on the Assiniboine River. On the far right of the canvas are the women and Métis family from Suzor-Coté and Rindisbacher’s works respectively. In the centre, walking behind the figures, is the apparitional figure of Miss Chief. As she is commanded to leave, she glances back to her homeland. As a result of her disobedience, she turns into a pillar of salt. While the historiography of past events cannot be changed, Monkman shows that the representation of these events can be rewritten. It is through the character of Miss Chief that such a restaging can occur.

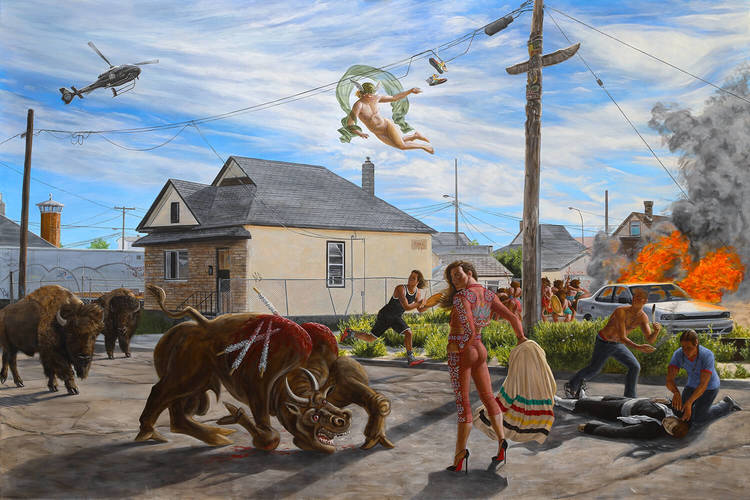

More recent interventions that expand the scope of this working method include important video works such as Dance to Miss Chief, 2010, in which a dancing Miss Chief is romantically interweaved among footage of Winnetou, a fictitious “Indian” who appears in Karl May’s German Western films. Another is the painting Seeing Red, 2014, which makes use of sophisticated stereotypical visual tropes drawn from art history in order to reverse the Western gaze. Miss Chief, clad in a bullfighter’s uniform adorned with contemporary Métis beadwork, uses a Hudson’s Bay blanket to engage a bull modelled after Pablo Picasso’s famous cubist works. The traditional matador lays dead nearby while a Hermes-like figure floats above, reaching for his winged sneakers that hang from a power line supported by an Indigenous Northwest Coast totem pole. Miss Chief stares directly at the viewer. The invocation is here obvious—traditions invented by Europeans are in the process of being replaced by a pan-Indigenous worldview capable of accomplishing what the Western gaze could not, to see beyond itself.

In 2017, Monkman received an invitation from Barbara Fischer, Executive Director and Chief Curator at the Art Museum of the University of Toronto, to create a solo exhibition that responded to the sesquicentennial of Canadian Confederation. After years of visiting museums that contained no history paintings conveying or authorizing Indigenous experience, Monkman unveiled the landmark exhibition, Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience. In this instance, Miss Chief was the narrator, a disruptive force, and transformative figure who reimagined Canadian history in radically different directions. Monkman curated the show and Miss Chief wrote the accompanying didactic panels, reframing Canada’s foundational myths in terms of her relations with the colonizers. Monkman’s large paintings, sculptures, and dioramas were placed alongside material culture, decorative arts, and objects mined from various museums and collections across Canada. In the installation’s nine chapters, Miss Chief recounted the Indigenous experience of nationhood. She unpacked modernity and primitivism by citing art historical references. She spoke about the early politics that shaped Canada, and she exposed the fallout of colonialism. She told the story of what Monkman calls “the worst 150 years in Indigenous peoples’ history.”[10]

Today, Miss Chief appears in paintings, videos, and performance works as both Indigenous saviour and interlocutor. She is a mythological figure who communicates resilience and sparks a necessary dialogue between settler and Indigenous worldviews. In this way The Deluge, 2019, is a clear example of her power to both respond and reclaim because it calls attention to the legacy of residential schools and the fact that, still today, Indigenous children are removed from their families and placed into foster care in record numbers. Accordingly, she is the lens through which we must read Monkman’s work. As she evolves and becomes otherworldly, this time traveller, who intervenes in colonial spaces past and present, actively engages with and destabilizes historical events. She welcomes newcomers, encounters historical figures, including artists, and uses sexuality as a tool to disempower the colonizer. By doing this and so much more, Miss Chief personifies the artistic tradition of refusal—because she embodies no fixed position.

_______

Shirley Madill is the executive director of the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. She has held curatorial and director positions at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of Hamilton, the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, and Rodman Hall Art Centre at Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario. She is author of the Art Canada Institute publication Robert Houle: Life & Work.

_______

Notes

[1] Monkman notes that “Cher had her half-breed phase, which was glamorous and it was gender bending at the same time.” See Jonathan D. Katz, “Miss Chief is always interested in the latest European fashions,” in Interpellations: Three Essays on Kent Monkman, ed. Michèle Thériault (Montreal: Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, Concordia University, 2012), 19.

[2] Kent Monkman, in conversation with the author, October 2019.

[3] Kent Monkman quoted in Ian McGillis, “Kent Monkman’s irreverent art turns the Canadian narrative on its head,” Montreal Gazette, February 14, 2019.

[4] George Catlin, Illustrations of the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians: With Letters and Notes Written During Eight Years of Travel and Adventure Among the Wild and Most Remarkable Tribes Now Existing: With Three Hundred and Sixty Engravings, from the Author’s Original Paintings, Volume 2 (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1844), 2:215.

[5] David McIntosh describes Miss Chief as a “Postindian Diva Warrior” in his essay “Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Postindian Diva Warrior, in the Shadowy Hall of Mirrors,” in the exhibition catalogue for The Triumph of Mischief (Hamilton: Art Gallery of Hamilton and Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 2008), 31–46.

[6] In more recent years Monkman has dropped Share and today she is called Miss Chief Eagle Testickle exclusively.

[7] Film still from Group of Seven Inches, written by Kent Monkman, co-directed by Kent Monkman and Gisèle Gordon (Toronto: Urban Nation/VTape, 2005), dvd.

[8] Cathy Mattes, “An Interview with Miss Chief Eagle Testickle,” in The Triumph of Mischief (2008), 103. George Catlin assembled his paintings and artifacts into his Indian Gallery that included personal recollections of his life among Indigenous peoples. He also staged performances.

[9] TVO Current Affairs, “Challenging Canada’s History Through Art,” TVO, July 5, 2017, https://www.tvo.org/ article/challenging-canadas-history-through-art.

[10] Kent Monkman, “Foreword,” in brochure produced in conjunction with the exhibition Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience (Toronto: University of Toronto Art Museum, 2017), 4.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix