The truism that (art) history is written by the victors has a particular relevance to the narratives and images created during the heyday of European colonial empires in the Americas. Sculptures and paintings made from the beginning of contact through to the twentieth century show Indigenous North Americans as figures who are destined to fade out of history. Kent Monkman’s mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) turns these stereotypical and romanticized images on their heads by confronting the viewer with a counter-narrative of the past, present, and future of Indigenous-settler relationships. Each panel of the diptych is built up out of separate vignettes that invert, subvert, and convert to vivid life the generic figures Monkman has found in the galleries of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Stereotypes are individualized, the passive figure becomes active, the vanquished raise up the former conqueror, and supposed victims are redrawn with the strength of their survivance.[1]

Revision and Resistance: mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, published by the Art Canada Institute, is now available for purchase. Click here to order your copy.

Cumulatively, however, the wealth of incident in Monkman’s diptych adds up to more than the sum of its parts, for his grandest appropriative gesture is the recruitment of the tradition of history painting itself to the service of a decolonizing agenda. For more than three centuries this genre, tasked with conveying the full weight of Western mythology, religion, and historical consciousness, stood as the most prestigious and demanding of Western painting practices. Artists illustrated scenes from Ovid and other classical writers, Biblical stories including the life of Christ, and proclaimed the glorious achievements of monarchs and heroes, in works that were ideally large in scale and intended for public viewing. Twentieth century modernism put an end to the genre’s primacy. And so when Monkman began to engage with history painting, as he did in works such as Birth of a Nation, 2012, he made a deliberate choice to take up a tradition most critics would have deemed long dead. In mistikôsiwak, Monkman represents the history of colonial-Indigenous relationships from an Indigenous perspective and, in so doing, claims history painting as a tool that can remove the paralyzing weight of settler historical narratives from Indigenous consciousness. It is the appropriation of a trickster; by endowing history painting with new relevance and purpose, Monkman—like the mythic beings whose magical powers reshaped and transformed the world at the time of creation—is also revalidating a great Western genre for the twenty-first century.

Acrylic on canvas, 152.4 × 213.4 cm, private collection

Before looking at the strategies Monkman uses to achieve these ends, it is helpful to recall the stories of first contact that Welcoming the Newcomers displaces, and how more recent historical work is correcting and revising colonialist narratives. The explorer Jacques Cartier’s accounts of his initial meetings with Iroquoian-speaking people along the Saint Lawrence River in 1534 and 1535 are good examples. Like other early reports, they are based on the observations of a man who arrived in North America with prejudiced expectations, mercantile and colonial agendas, and no common language.[2] Cartier describes his encounter with a group of people camping in Gaspé Bay during their annual seal hunt. Both the Indigenous and French parties set out offerings—seal meat on one side, hatchets, knives, beads, and other wares on the other. Several Indigenous women: “advanced freely towards us and rubbed our arms with their hands. Then they joined their hands together and raised them to heaven, exhibiting many signs of joy. And so much at ease did they feel in our presence, that at length we bartered with them, hand to hand, for everything they possessed, so that nothing was left to them but their naked bodies, for they offered us everything they owned, which was, all told, of little value. We perceived that they are people who would be easy to convert, who go from place to place maintaining themselves and catching fish in the fishing-season for food.”[3] The text immediately establishes the tropes of Indigneous passivity, naiveté, credulousness, and—from a European point of view—irrational generosity and lack of trading acumen that would inform subsequent representations. It universalizes a European cosmology in which the sky equals “heaven” and is blind to the cosmological references signalled by the Indigenous gestures of welcome. It conceives of exchange as an extractive process in contrast to Indigenous models of reciprocity. The voracious appetite for Indigenous possessions and the agenda of religious conversion are chilling auguries of the dispossessions, impoverishments, and suppressions of Indigenous spirituality that will result from European contact.

The misunderstandings and cultural hierarchies embedded in such narratives have been deeply inscribed in settler consciousness through a wide range of popular arts ranging from prints, plays, pageants, and photographs, to films, animations, and museum installations. Many of these representations have depended on imagery invented by history painters. A prominent example is Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté’s monumental painting of Cartier’s meeting with the inhabitants of Stadacona (Quebec City) in 1535 that has hung in Quebec’s provincial museum since its opening.[4] Made in 1907, it testifies to the tenacity of the early-modern tropes of first contact. Cartier is represented in aristocratic clothing, standing erect in the centre of the painting while the Indigenous leaders cower in the trees. As art historian Laurier Lacroix has noted, the light illuminating the scene comes from the east, the direction of Europe.[5] More recent scholars understand these encounters differently. Métis historian Olive Dickason stresses the long history of social and cultural changes in the region preceding European contact and reasons that “what happened afterward may well have been a continuation of these processes and developments in which European-related factors would have had a modest role at best.”[6] It is clear that, during the early years of contact, colonizers and Indigenous nations strove to assimilate each other to their own moral and political economies. In New France, as Matthew Dennis puts it, “the French and the Five Nations each sought the transformation of the other, on terms dictated largely by themselves.”[7]

-article-image.jpg)

Oil on canvas, 264.5 × 401 cm, Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

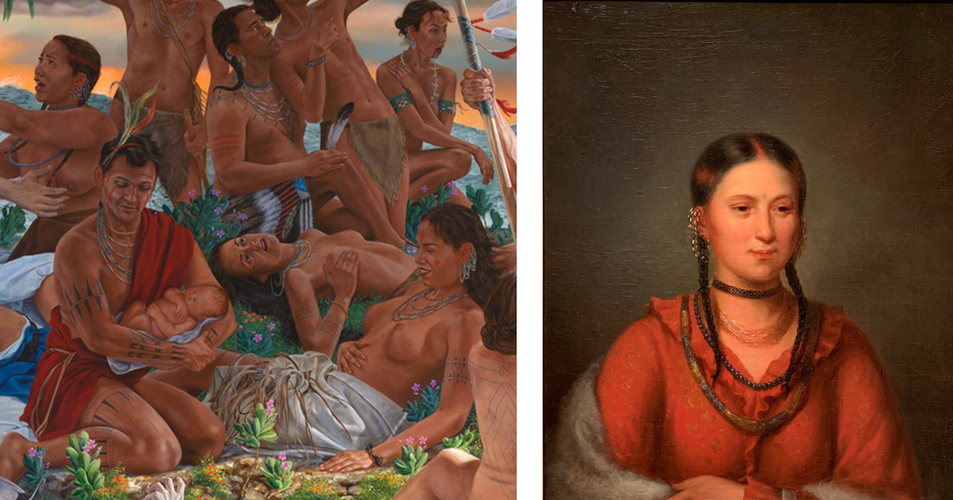

In Welcoming the Newcomers, Monkman stays true to history painting’s classic focus on the representation of ideals, values, and moral principles rather than factual historical events. He gives us a scene fully in keeping with William Aglionby’s classic definition of history painting as an “Assembling of many Figures in one Piece, to Represent any Action of Life, whether True or Fabulous, accompanied with all its Ornaments of Land-skip and Perspective.”[8] The painting centres on a single mythic, allegorical figure: Monkman’s alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. In her most recent iteration, Miss Chief is endowed with a new gravitas; her stylish high heels are the lone remnant of the glamorous, camp persona we have come to know and love from her previous embodiments in Monkman’s work as seductress and trickster. In mistikôsiwak, Miss Chief personifies generosity, charity, and compassion, bending down to help an eclectic miscellany of abject figures who struggle to come ashore: a soldier of the Spanish Main, a half drowned sailor, a Pilgrim, a French fille du roi, an Ottoman mercenary, a shackled African slave—forerunners of the millions seeking refuge from want and oppression who will arrive in future centuries. Gazing directly at the viewer, and perhaps into the future, Miss Chief ’s expression is sombre and filled with foreboding. She seems to foresee the dispossession and death her welcome is ushering in. A tall male figure stands next to Miss Chief, looking on at the scene. Like her, he bears Monkman’s own features. This powerful juxtaposition evokes the respect and honour traditionally accorded to two-spirit people in Indigenous societies—values that would be suppressed and silenced by colonial regimes.[9] To the left, balancing these central figures, is a family group, the man holding a baby and the woman reclining next to them.

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

Right: Henry Inman, Hayne Hudjihini, Eagle of Delight, 1832–33

Oil on canvas, 76.8 × 64.1 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The source for this vignette is Eugène Delacroix’s The Natchez, begun in 1823 and completed in 1835, in The Met’s collection. It depicts characters from Atala, ou Les Amours de deux sauvages dans le désert, François-René de Chateaubriand’s popular novella, published in 1801, after his return from his travels in North America. In the epilogue, Chateaubriand’s narrator describes his encounter with a young couple holding their dead child. They are, the mother tells him, the “remnants of the Natchez” who, after a massacre by the French, had found refuge with the Chickasaw only to be again dispossessed when “the white people of Virginia seized our lands.”[10] The narrator relates that the child’s death was caused by its mother’s grief-tainted milk. Delacroix’s picture—romanticized, mournful, elegiac—captures the sentimentality with which many Euro-Americans voiced their belief in the inevitable disappearance of Indigenous peoples in the face of settler expansionism. Here, again, the colonial texts have the force of self-fulfilling prophecies. The powerful Natchez chiefdoms had, in fact, successfully resisted French domination during the early contact period, despite the devastation wrought by epidemic diseases, forced dislocations, and armed conflicts. Although the French-Natchez wars of the 1720s–40s had made refugees of many Natchez and resulted in the enslavement of others, they survive to this day as distinct cultural groups both in their original homelands and in present-day Oklahoma.

Oil on canvas, 90.2 × 116.8 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Right: Kent Monkman, Resurgence of the People (detail), 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

In his re-painting of Delacroix’s original, Monkman transforms the little family, replacing the parents’ expressions of grief and despair with contentment and pride. Instead of the generic features in the Delacroix, Monkman gives the mother the face of Hayne Hudjihini, or Eagle of Delight, taken from a painting by Henry Inman, also in The Met’s collection.[11] Monkman’s use of this portrait acknowledges both an obligation to restore the individuality of historical figures, and the indexical value of portraits made from life by colonial artists, even when motivated by the myth of disappearance. Monkman performs similar acts of recuperation and correction elsewhere: for example, in his representation of Pocahontas on the lower left of the painting. In keeping with the image constructed for her over the centuries, she wears the blue cloak seen in depictions of the Virgin Mary. But Monkman also paints her with the Indigenous tattooed designs recorded in the sixteenth century by British artist John White during his travels in the Virginia colony. In contrast, when Monkman turns to the present and future in Resurgence of the People, the faces of his figures are taken from the living models he photographs in his studio. And as a sign of the recovery and rescue depicted in that painting, the family from The Natchez reappears on the right side of the composition, this time in the form of a same-sex couple.

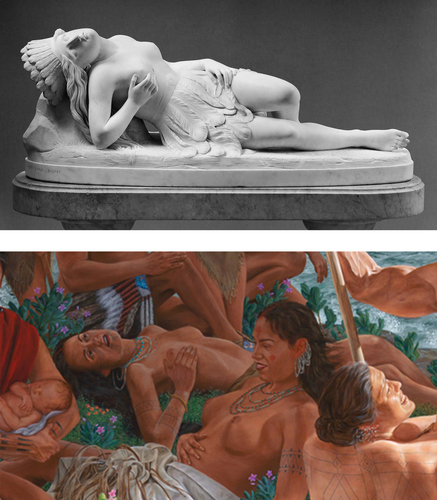

Marble, 51.4 × 138.4 × 49.5 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Bottom: Kent Monkman, Welcoming the Newcomers (detail), 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

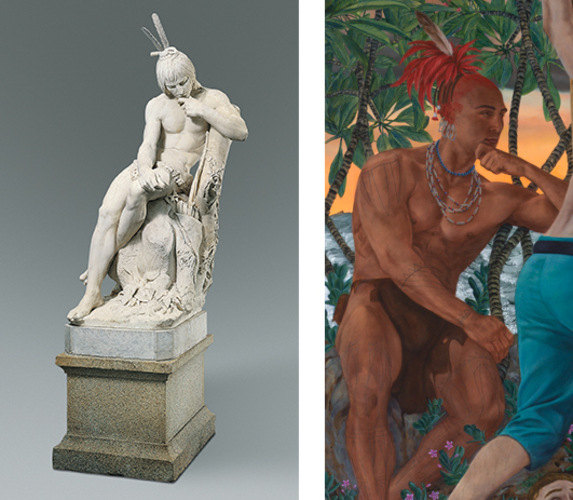

Similar interventions occur in adjacent figures in Welcoming the Newcomers. Behind the family is a reclining female figure based on Thomas Crawford’s Mexican Girl Dying, 1848, in The Met. Like Delacroix, Crawford was inspired by a specific text: William H. Prescott’s 1843 History of the Conquest of Mexico. Like the mythical Cypriot sculptor Pygmalion, Monkman breathes life into the marble sculpture, erasing the mortal wound she fingers with her right hand as well as the crucifix next to her left hand—a reference to Prescott’s argument that the Spanish motivation for colonization, religious conversion, had redeemed the violence and death brought by conquest. In place of the pathos of Crawford’s image, Monkman restores colour and sensuous life to the girl’s body and removes the inaccurate feather garments derived from Amazonian Indigenous dress.[12] In parallel with these transformations, a series of male figures at the back of the composition reference and recuperate a number of the classicizing, romantic bronze sculptures popular with American art collectors during the second half of the nineteenth century. On the far left, a seated man wearing an eagle feather and loincloth brings to life Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Hiawatha, 1874, its eponymous subject among the most misrepresented of Indigenous historical leaders. While the historical Hayo’wetha was the Onondaga co-founder of the Haudenosaunee confederacy, which, many historians think, provided a political model for the confederation of the thirteen American colonies, Longfellow’s epic poem about the leader conflates him with the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) culture hero Nanabozho.13 Here, again, Monkman corrects stereotypes, giving Hayo’wetha a necklace of the wampum beads with which he healed his own and others’ grief, in addition to a historically accurate headdress and tattoos.

Marble, figure: 152.4 × 87.6 × 94.6 cm; granite base: 58.4 cm; plinth with inscription: 14.6 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Right: Kent Monkman, Welcoming the Newcomers (detail), 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

To Hayo’wetha’s right, the man who reaches into his quiver for an arrow is based on Henry Kirke Brown’s 1849 bronze, Choosing of the Arrow. Although Brown, unlike Saint-Gaudens, visited the Anishinaabe in the American Midwest, he nevertheless represented the subject of his sculpture in the classical contrapposto pose favored by fifteenth-century Italian Renaissance masters. His hunter is an iteration of the noble savage construct that itself referenced the early-modern European notion of hunting as a privilege of the aristocracy. Monkman leaves us with an ambiguity: there is equal reason to think that the arrow will be launched against the further encroachments of settlers.

When looking at one of Kent Monkman’s virtuoso exercises in art-historical cross-referencing it is hard to resist the temptation to be drawn further into the dense maze of visual quotations he constructs for our pleasure. Every figure in the two panels that make up mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) has been created through a similar process of reversal, inversion, recolouration or recombination. In the end, however, all these masterful turns have a much larger purpose. Why, we need to ask, does Monkman take us on this journey?

On one level, the answer has to do with a fundamental human right to what philosopher Charles Taylor calls “recognition.” Taylor points to the debilitating impact on individuals who live in a society that constantly projects onto them inaccurate and often demeaning identities. As he puts it, “non-recognition or misrecognition can inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, and reduced mode of being.”[14] By demolishing the stereotypical portrayals of Indigenous people, Monkman’s decolonization of history painting does the critical work of psychic healing. In breathing life into the so-called “Indians” of Western art history, he exposes the key tenet of settler false consciousness—the conviction that Indigenous peoples would vanish, leaving uncontested title to their lands to the descendants of the immigrants who clamber ashore in Welcoming the Newcomers. The means by which this disappearance would be accomplished have varied: violent conquest, the spread (both unintended and intended) of epidemic diseases, outright thefts of land and the blatant ignoring of treaties, projects of forced assimilation through punitive laws, and the traumatic removal of children to boarding and residential schools. But there has also been the brainwashing attempted by the endless repetition of the triumphalist, racist settler historical narrative that has frequently been projected by history painting itself.

-article-image.jpg)

Bronze, 55.9 × 28.9 × 14.3 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Right: Kent Monkman, Welcoming the Newcomers (detail), 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

On another level, however, mistikôsiwak is a response to a question Monkman posed to himself in 2017. In his foreword to the brochure for his exhibition Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, a tour-de-force that re-narrates the settler-colonial history of Canada with such haunting works as The Scream, 2017, Monkman described his strong response to history paintings he viewed in European museums. “I could not think of any history paintings that conveyed or authorized Indigenous experience into the canon of art history. Where were the paintings from the nineteenth century that recounted, with passion and empathy, the dispossession, starvation, incarceration and genocide of Indigenous people here on Turtle Island? Could my own paintings reach forward a hundred and fifty years to tell our history of the colonization of our people?”15 His affirmation of the value of history painting, he further wrote, is tied to a rejection of the twentieth-century art world’s romance with modernism, a period that—not coincidentally, in Monkman’s view—coincides with the most oppressive years of forced assimilation policies.

The double game Monkman plays is compelling because it is simultaneously celebratory and adversarial, playful and serious. Grounded in a complete aesthetic commitment and an equally profound political activism, it is relieved by humor and self-reflexivity. He stakes a claim of ownership to history painting and re-deploys it to remediate its damage. The double meaning of his title says it all: “Wooden Boat People” is the term Monkman’s ancestors gave to the European arrivées, but it also applies to the contemporary band of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who voyage into the future, piloted by Miss Chief and seeking refuge from historic trauma and looming global disaster, in the wooden boat George Washington used to cross the Delaware. Through appropriation and redirection, Miss Chief turns a Western watercraft technology into a strategy for salvation, even as Kent Monkman deploys canvas, paint, and the genre of history painting as a strategy for decolonizing understandings of our shared history. If Monkman’s engagement with Western art history both critiques its misrepresentations and locates his own practice within its traditions, the mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) diptych extends this practice of recovery into a future where Indigenous values offer hope to those displaced in a world ravaged by centuries of colonialism.

-article-image.jpg)

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 × 320 cm, Denver Art Museum

Ruth B. Phillips is Canada Research Chair and professor of Art History at Carleton University and has served as director of the Museum of Anthropology at UBC, Vancouver. She is a specialist in the Indigenous arts of North America and critical museology, and her recent publications include Museum Pieces: Toward the Indigenization of Canadian Museums (2011); Native North American Art (2nd edition, 2014) with Janet Catherine Berlo; and Mapping Modernisms: Art, Indigeneity, Colonialism (2018), co-edited with Elizabeth Harney.

Mark Salber Phillips, professor emeritus of History at Carleton University, is a specialist in the history of ideas. Among his publications are The Memoir of Marco Parenti: A Life in Medici Florence (1987); Society and Sentiment: Genres of Historical Writing, 1740–1820 (2000); and What Was History Painting and What is it Now? (2019), co-edited with Jordan Bear. His 2013 book On Historical Distance was awarded the Canadian Historical Association’s Ferguson prize.

This essay is published in Revision and Resistance: mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art under the full title of “Welcoming the Newcomers: Decolonizing History Painting, Revisioning History.” The title has been shortened for publishing online.

___________

Notes

[1] The term “survivance,” which combines notions of survival and resistance, is theorized by Indigenous literary scholar Gerald Vizenor as “an active sense of presence over absence, deracination, and oblivion.” See “Aesthetics of Survivance: Literary Theory and Practice” in Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence, ed. Gerald Vizenor, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 1.

[2] The St. Lawrence Iroquoians whom Cartier met probably integrated with Wendat and Haudenosaunee nations during the century following these meetings. See Jennifer Birch, “Current Research on the Historical Development of Northern Iroquoian Societies” in Journal of Archaeological Research 23 (2015): 291–292. It is probable, although debated, that the accounts of Cartier’s voyages published in the seventeenth century were based on his ships’ logbooks but not written by Cartier himself. See Marcel Trudel, “Jacques Cartier” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, accessed November 10, 2019, http://biographi.ca/en/bio/cartier_ jacques_1491_1557_1E.html.

[3] The Voyages of Jacques Cartier, ed. H.P. Biggar (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1924; repr. 1993), 22.

[4] The painting remains prominently positioned. It is, however, reframed by a new audio accompaniment that acknowledges the colonial narrative it embodies. Accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ba7EobHQumY#action=share.

[5] Laurier Lacroix, Suzor-Coté: Light and Matter (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2002), 139.

[6] Olive Patricia Dickason, Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times, 3rd ed., (Don Mills, on: Oxford University Press, 2002), 82.

[7] Matthew Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace: Iroquois-European Encounters in Seventeenth-Century America (Ithaca, ny: Cornell University Press, 1993), 213.

[8] William Aglionby, “Explaining the Art of Painting,” in Painting Illustrated in Three Diallogues [sic] Containing some Choice Observations upon the Art Together with the Lives of the Most Eminent Painters from Cimabue to the Time of Raphael and Michelangelo With an Explanation of the Difficult Terms, unpaginated (London, U.K.: John Gain, 1685), accessed November 25, 2019, https://archive.org/details/paintingil-lustra00agli/page/n39.

[9] For a discussion of Anishinaabe understandings of gender see Anton Treuer, The Assassination of Hole in the Day (Blue Hill, me: Borealis Books, 2011).

[10] François-René de Chateaubriand, Atala; René, trans. Rayner Heppenstall (Cornwall, uk: mpg Book Groups, 1963), p. 76.

[11] Inman based his portrait on one made from life in 1822 by Charles Bird King. As part of its Native Perspectives project (see “Introduction from The Metropolitan Museum of Art,” p. 13), The Met invited two descendants of Haini Hudjihini, Veronica Rock and Wolf Pipestem (Otoe-Missouria), to respond to the Inman portrait. Their comments bring into relief the combination of active resistance and deep loss characteristic of settler-Indigenous relationships in the nineteenth century: “Following a peace treaty in which the Jiwere-Nut’achi agreed to an alliance with the United States government, in 1822 she and her husband traveled as ambassadors and protectors of Jiwere-Nut’achi sovereignty from their home in present-day Nebraska to Washington, D.C., to meet with President James Monroe. During this trip, Bureau of Indian Affairs superintendent Thomas McKenney is said to have fallen in love with her and commissioned her portrait. Despite Eagle clan members being known for their strength, health, and long lives, she died of measles shortly after she returned home.” Accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curato- rial-departments/the-american-wing/native-perspectives.

[12] Mestizo poet Livia Corona Benjamin’s “Thomas Crawford, Mexican Girl Dying,” written in response to The Met’s invita- tion to contribute to its Native Perspectives project, movingly relates past to present tragedies, and thus early contact period to contemporary colonialism and racism. It begins: “Silencio. Be quiet. / There is a Mexican / Girl Dying, amongst / the sculptures and decor- / ative objects that / dress the American / Wing. Mantelpieces, / fountains, ornament, / dead centerfold-pose / Exposed, cross / in hand, without / citizenship.” It ends: “A Mexican / girl is dying. / We know why some girls / from Mexico / die and others / do not.” Accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.metmuseum.org/ about-the-met/curatorial-departments/the-american-wing/ native-perspectives.

[13] Tlingit artist Jackson Polys’s Native Perspectives intervention emphasizes the political function of such representa- tions to the realization of America’s “manifest destiny”: “To trace the arc of the hunched back of this imagined Indian is to follow the call for the end of the wild. Longfellow’s ethnographic errors while naming the nature of this man matter less than repeating a self-fulfilling prophecy in service of a new national tribe, which relies on the neutering of the Indian problem. This body is depicted with sensitive restraint in a state of retreat, requiring the quiver down and weapons appropriately at rest, in order to keep the future settled. This projection helps us come to terms with and justify the foundational violence of wars unfortunately won. Americans, aided by the work of artists, become Native, and Natives are incorporated into the national narrative.” Accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.metmuseum.org/ about-the-met/curatorial-departments/the-american-wing/ native-perspectives.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix