The nineteenth-century painter Paul Kane (1810–1871) was the first and only artist in Canada to embark upon a pictorial and literary project featuring the country’s Indigenous peoples, using the medium of portraiture in a time before the dominance of photography. Kane was working within a model initiated by Swiss artist Karl Bodmer (1809–1893) and American artist George Catlin (1796–1872) and adopted by Americans such as Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874), John Mix Stanley (1814–1872), and Seth Eastman (1808–1875), all of whose public profiles were enhanced through exhibition and publication.

Paul Kane, Head Chief of the Assiniboines (Portrait of Mah-min), Assiniboine, c.1849–56

Oil on canvas, 76.3 x 63.9 cm, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

Kane’s objective, according to the preface of his book Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America (1859), was to “sketch pictures of the principal chiefs, and their original costumes, to illustrate their manners and customs, and to represent the scenery of an almost unknown country.” It was a challenge to which he rose, despite the numerous obstacles, such as cultural differences, harsh terrain, and the difficulty of obtaining patronage. During his travels Kane encountered over thirty different tribes, and he painted their vibrant cultural traditions as well as individual portraits.

George Catlin’s Indian Gallery paintings installed alongside Native American dioramas, at the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., c.1901.

Kane’s mission to record the life of Indigenous peoples of the Northwest has all the hallmarks of what later became known as the salvage paradigm in which a dominant society attempts to save through documentation the culture of another that it considers to be at risk of vanishing. This motivation is particularly clear in George Catlin’s Indian Gallery project, created in direct response to the U.S. government’s agenda to remove the Indigenous people to reservations. Although Canadian policy was less overt, this idea did have currency in Canada and was mentioned in 1852 in the context of an exhibit of Kane’s paintings. Kane’s attitude seems to have supported the salvage imperative as he accepted the inevitability of the Indigenous peoples’ demise caused by the relentless encroachment of Western civilization.

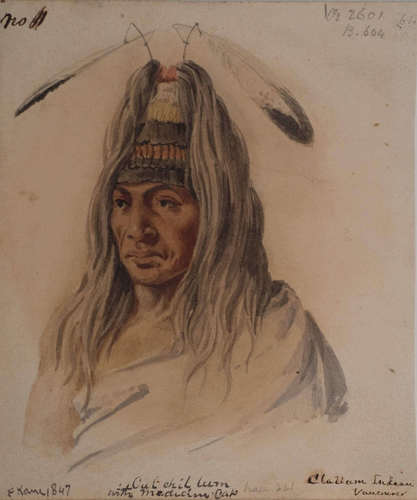

Paul Kane, Culchillum Wearing a Medicine Cap, April–June 1847

Watercolour on paper, 12.3 x 11.4 cm, Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas

His legacy, which documents a unique aspect of Canadian history, is threefold: the hundreds of sketches and drawings; the ensuing cycle of one hundred studio paintings; and the journal he wrote, with its subsequent incarnation as an illustrated book. Yet a conundrum lies at the heart of Kane’s work. Contemporary critical analysis pegs Kane as an appropriator who profited from picturing the lives of disempowered Indigenous peoples, and even as a racist who failed to adequately respect the cultures he encountered and portrayed. The works he produced reflect the prevailing attitudes toward Indigenous peoples held by white society in the mid-nineteenth century; the oil paintings featured the trope of the “noble savage,” making them particularly compelling in the artist’s day. Wanderings of an Artist likewise reinforced this attitude, a stereotype that was a product of the Western world’s Romantic vision of Indigenous people and their ancestral lands, which had been colonized by Europe.

Paul Kane, Scalp Dance, Colville, Colville (Interior Salish), c.1849–56

Oil on canvas, 47.9 x 73.7 cm, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

However, Kane did make copious detailed and accomplished renderings of individuals and their thriving and vital culture. By today’s sensibilities it is the hundreds of sketches that Kane produced that are most compelling. Regarded as fresh and immediate, the sketches are valued as bearers of authenticity, created by an eyewitness with a fine talent for capturing the subject matter before him. His work has no photographic parallel, for no one had yet turned a camera on the prairies and beyond. Kane thus built an enduring and valuable primary visual record of a culture that we otherwise would not have.

This Essay is excerpted from Paul Kane: Life & Work by Arlene Gehmacher.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans