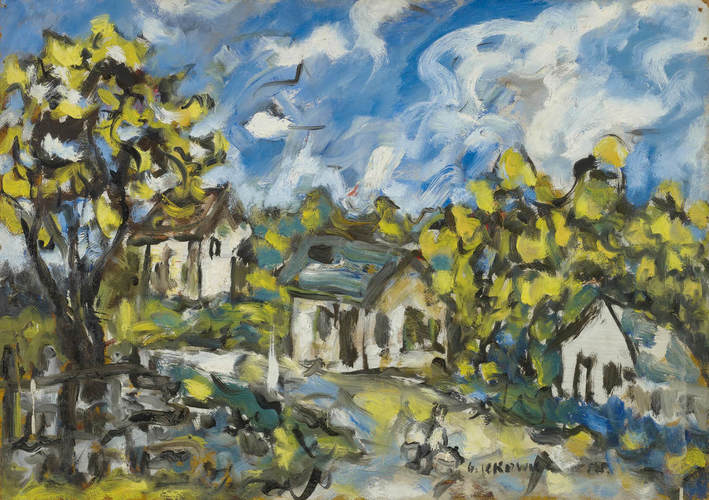

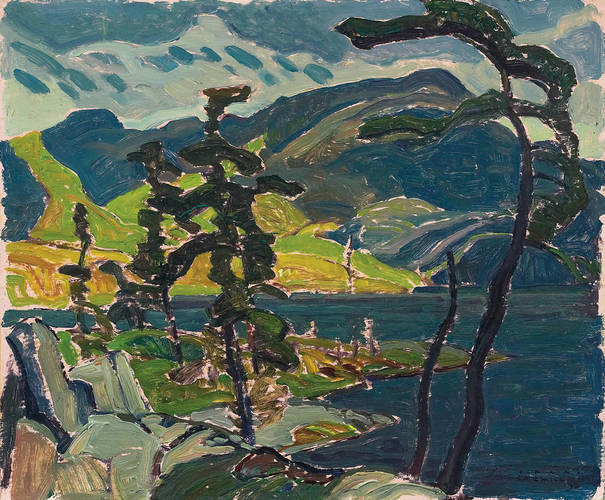

A Polish immigrant and Holocaust survivor, Gershon Iskowitz (1919–1988) arrived in Toronto in 1948 and found his place in Canadian art in the mid-1950s when he switched his subject matter from memories to landscapes, initially in the Parry Sound area north of the city. While a stylistic comparison can be made between works by Group of Seven artists—like Spring, Cranberry Lake, 1932, by Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945)—and Iskowitz’s work of this period, his painting was not a “project of the land.” Rather, it was a way out of his memories of Poland and the concentration camps, allowing him to break with the past and begin a new life as an artist in Canada.

Oil on board, 46 x 65 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Around 1960 Iskowitz stopped painting literal landscape works and made a significant shift toward abstraction—as in Late Summer Evening, 1962, and Spring Reflections, 1963. While he maintained some pictorial elements in these beautifully coloured paintings, he dissolved the skies into glowing ribbons of light and deconstructed tree forms into brightly hued shapes that seem to explode outward from their trunks. He followed this artistic trajectory for the rest of his life. Iskowitz never explained the reason for this change, but perhaps, amid the freedom and independence he now enjoyed, he decided to pursue his own visual language and discover where it led.

Oil on canvas, 25.1 x 30.4 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

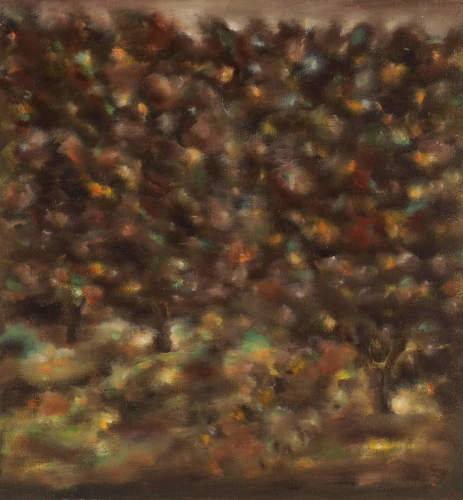

By the late 1960s Iskowitz’s abstract pieces had become larger, with reduced elements—as in Autumn Landscape #2, 1967—and they fit with the progressive art being made at that time. Works by Painters Eleven members Jack Bush (1909–1977) and Harold Town (1924–1990), for instance, echoed the dominant trends in painting in the United States and Europe as well as in Canada.

In 1966 Harry Malcolmson was the first art critic to position Iskowitz in the Toronto art scene. In the text he wrote for Iskowitz’s solo exhibition at Gallery Moos, he grappled with questions of how Iskowitz’s abstract style fit into the contemporary scene, describing how “[Iskowitz’s] Canadianism comes out directly in [his] subjects [of] this country’s landscape . . . . His personal vision and warmth at first foreign has passed into the community and after a period of time has become an integral part of it.”

Oil on canvas, 76.3 x 71.1 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Critic Kay Kritzwiser’s review of the 1966 exhibition described Iskowitz’s recent work as a “lyric abstraction” that he was now applying “to a countryside usually painted with Group of Seven eyes. Iskowitz,” she wrote, “makes us look at it anew.” In fact, as Malcolmson had astutely noted, Iskowitz had turned his view away from the horizon line, which defines a view of the land, and looked instead to the sky. He used colours from the land and applied them to the sky, and, because the sky has no shape or form, the works became abstract.

Oil on canvas, 94 x 116.8 cm, private collection, Toronto

On the few occasions when Iskowitz talked to art critics about his art practice, he defended his independence and refused to be described by any of the common labels. In a 1975 interview with Merike Weiler, he said:

People say, oh, Gershon Iskowitz is an abstract artist. . . . But it’s a whole realistic world. It lives, moves . . . I see those things . . . the experience, out in the field, of looking up in the trees or in the sky, of looking down from the height of a helicopter. So what you do is try to make a composition of all those things, make some kind of reality: like the trees should belong to the sky, and the ground should belong to the trees, and the ground should belong to the sky. Everything has to be united. . . .

Oil on canvas, 101.8 x 81.5 cm, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

Iskowitz was expressing something beyond the literal, just as instrumental music is formed with sound, tempo, and interval (the space between the sounds), not words. For him the sky was a universal view, one we can all experience regardless of where we live.

This Essay is excerpted from Gershon Iskowitz: Life & Work by Ihor Holubizky.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans