In the spring of 1949, the anglophone Montreal painter Paterson Ewen (1925–2002) attended a talk where he met Françoise Sullivan (b. 1923), a painter, dancer, and member of the Automatistes, a group of avant-garde Québécois artists. Ewen was completely taken by Sullivan, and she by him. Soon she introduced him to other Automatistes.

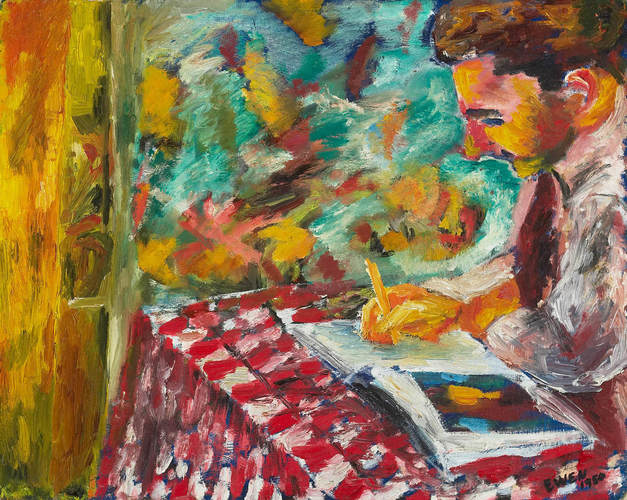

Paterson Ewen, Portrait of Poet (Rémi-Paul Forgues), 1950

Oil on canvas board, 40.6 x 50.8 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Inspired by the European Surrealist movement, they had released the Refus global in 1948. The manifesto advocated freedom by using the subconscious as a tool of liberation against the oppression of the Roman Catholic Church and the traditionalist conservative politics of Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis. The latter had dominated the political landscape from 1936 to 1959, a period referred to as La Grande Noirceur (The Great Darkness). Artistically, the Automatistes sought to develop an abstract language of the subconscious that avoided the perceived ineffectiveness of figurative analogy, just as the Abstract Expressionists were attempting to do in the United States.

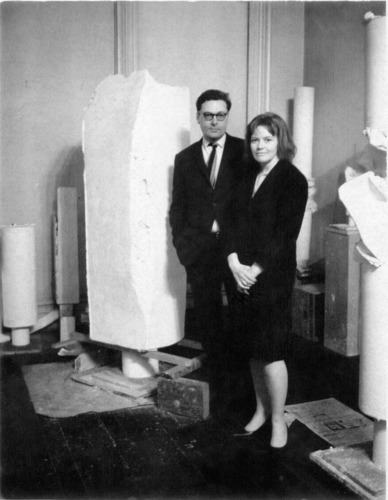

Paterson Ewen and Françoise Sullivan in New York, 1957

Photographer unknown, Dance Collection Danse Archive, Toronto

The Automatistes had a profound impact on Ewen, who explained, “I integrated into the French side without completely losing the English side. [. . .] I would sit without taking part in the conversation all that much, but of course it was very enriching.” As can be seen in Portrait of Poet (Rémi-Paul Forgues), 1950, the influence of the Automatistes on Ewen’s work is not obvious at first; his work remains figurative. However, stylistically his brushwork becomes far looser, to the point that one strains at times to identify specific objects in a scene, and he begins to experiment with colour combinations and contrasts that recall those in the abstract paintings of the French Canadian artists. The Automatistes recognized this affinity, writing favourably about Ewen’s figurative paintings and inviting him to exhibit with them.

Paterson Ewen with his sons, c.mid-1960s

Photograph by Françoise Sullivan

By the fall of 1949 Sullivan was pregnant, and she and Ewen married in December. The following year, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts chose two of Ewen’s works for its 67th Annual Spring Exhibition, held in March. The jury, however, rejected all of the Automatistes’ submissions, except one by Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960). The group countered with its own show, L’Exposition des Rebelles, which included a couple of Ewen’s landscapes. Borduas and Ewen were the only artists represented in both exhibitions, and these were the first public showings of Ewen’s art.

Ewen painted his first abstract work near the end of 1954. His involvement with the Automatistes certainly contributed to his move away from the figurative, though he could never paint as spontaneously as they did since he always needed structure to form his images. Nor could he fully embrace the hard-edged geometric canvases of the Plasticien painters, led by Guido Molinari (1933–2004).

Eighteen members of the Non-Figurative Artists’ Association of Montréal (NFAAM)

From left, starting lower left: L. Belzile, G. Webber, L. Bellefleur, F. Toupin, F. Leduc, A. Jasmi, C. Tousignant, J.-P. Mousseau, G. Molinari, J.P. Beaudin, M. Barbeau, R. Millet, P. Ewen, R. Giguère, P. Landsley, P. Gauvreau, P. Bourassa, and J. McEwen, 1957

Photograph by Louis T. Jaques

Nevertheless, or maybe because of this, Ewen moved fluidly between the waning Automatistes and the emerging Plasticiens. He showed his abstract work for the first time publicly at Espace 55, organized by Claude Gauvreau (1925–1971) at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Soon afterwards he exhibited at Molinari’s newly opened Galerie L’Actuelle, and he became a founding member of the Non-Figurative Artists’ Association of Montréal that Molinari helped create in February 1956.

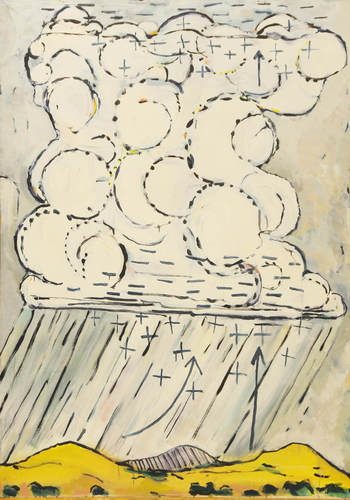

Paterson Ewen, Thunder Cloud as Generator #1, 1971

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 152.4 cm, Museum London

Over the next ten years Ewen’s artistic output was limited but nevertheless impressive. But by the mid-1960s his family life was crumbling, and in November 1966, Ewen and Sullivan formally separated. Ewen fell into a deep depression. He would eventually seek treatment in London, Ontario, where he underwent electroconvulsive therapy, with encouraging results. He had thoughts of returning to Montreal and rejoining his wife and family, but his doctor strongly advised against it. Ewen decided to settle in London, where teaching and connections to a thriving regional art scene would provide stability as he carried the influences of his abstract work into new, figurative, realms.

This Essay is excerpted from Paterson Ewen: Life & Work by John G. Hatch.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans