During his eleven years in New France (1664–75), the Jesuit priest and illustrator of seventeenth century Canada Louis Nicolas (1634–post 1700) travelled from the western end of Lake Superior to Sept-Îles (at the eastern end of New France), and from Trois-Rivières to the Iroquois lands south of Lake Ontario, his trips interspersed by numerous visits to Quebec. All of these trips were made at the behest of his Jesuit superiors, but he seems to have initiated at least one himself to a place he called “Virginia,” south of Lake Erie.

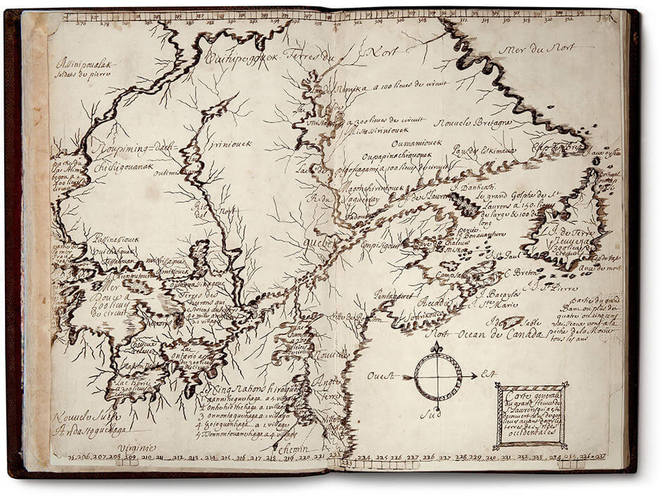

Louis Nicolas, Map, Codex Canadensis, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 43.2, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma. The map depicts the “Manitounie,” the Mississippi River region.

The Jesuits had arrived in New France in 1611 with the goal of converting the Indigenous peoples to Christianity, and Nicolas’s first mission was to Chequamegon Bay, an isolated post situated on the southwest bank of Lake Superior. On August 4, 1667, Father Claude Allouez had returned to Sillery from the Saint-Esprit Mission in Chequamegon to recruit some “worthy men” as well as a missionary with facility in Algonquin. Nicolas was chosen as the man to go. Their journey was arduous: Marie de l’Incarnation, the founder of the Ursuline Order of nuns in Canada, reported that the Indigenous guides were overloaded and, when they reached Montreal, they threw the priests’ baggage onto the shore.

A map showing the range of Louis Nicolas’s missions.

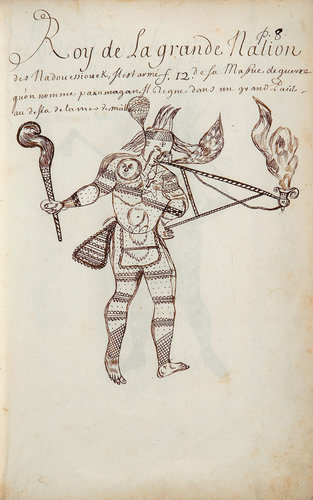

Allouez left Nicolas in charge of the mission at Chequamegon and continued on alone up the Baie des Puants (Green Bay) on Lake Michigan, where he founded the Saint-François-Xavier Mission. Chequamegon was in Outaouaks (Ottawa) territory, part of the larger Northern Algonquin lands, and, as a centre for trade in the region, it afforded the opportunity for contact with people from many surrounding groups. As such, it was an ideal location for a mission—and, as it turned out, for the documentary artist (Nicolas’s King of the Great Nation of the Nadouessiouek, Portrait of a Famous One-eyed Man [Portrait d’un Illustre borgne], and Fishing by the Passinassiouek [La pesche des Sauvages], all n.d., illustrate some of the Indigenous leaders he met there as well as some of the customs and implements he observed). He also travelled widely from this base: his major work, the Codex Canadensis, includes drawings of Illinois and Sioux chiefs, a Mascouten man, and an Amikouek man, all of whom he would have encountered in a large area around Lake Huron and extending north.

Louis Nicolas, King of the Great Nation of the Nadouessiouek (Roy de La grande Nation des Nadouessiouek), Codex Canadensis, page 8, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Within the year, Nicolas returned to Quebec, possibly sent back because of his bad temper and vanity. Antoine Alet, secretary of Gabriel de Queylus, Superior of the Sulpicians of Montreal (an order of priests engaged mainly in parish work), said the Algonquin chief Kinonché had complained that Nicolas had beaten him with a stick—even though he was the leader of a nation. Nicolas had also boasted that, when he arrived in Montreal, he would celebrate mass dressed in magnificent gold and silver garments, proving to the people how well respected he was. When the Sulpicians learned about these boasts from Kinonché himself, they refused to allow Nicolas to celebrate high mass.

Louis Nicolas, Drawing of the Sun (Figure du soleil), Codex Canadensis, page 4, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Although Nicolas possessed a genuine passion for missionary work, his avid interest in natural history and travel, along with his rude manners, eventually made it impossible for him to meet the standards demanded by his Jesuit superiors. In 1675 he was sent back to France. The final mark against him may possibly have been that he kept two captured bear cubs in the grounds of the Jesuit residence in Sillery and trained them to do tricks, with the idea of bringing them back to France and presenting these “curiosities” to King Louis XIV himself.

Louis Nicolas, The Whistler (Le siffleur), Codex Canadensis, page 29, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

This Essay is excerpted from Louis Nicolas: Life & Work by François-Marc Gagnon.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans