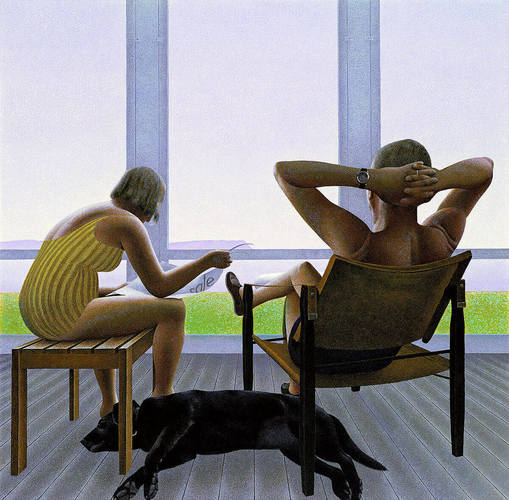

Animals play a key role in the art of Nova Scotia painter Alex Colville (1920–2013), often standing in as a counter to human figures. The animal is Other, present, seemingly ubiquitous in Colville’s imagery, but essentially unknowable. As his daughter, Ann Kitz, told curator Andrew Hunter, “He wasn’t sentimental about animals, but he thought that they were essentially good, and he didn’t think that people were inherently good.” Colville uses animals as a compositional pairing—such as in Dog and Groom, 1991—that forms an essential binary in his work: human/animal or, perhaps more accurately, culture/nature. For Colville, humans think, animals act, and in their juxtaposition something important about the world can be expressed. As Hunter notes, “Colville’s bond with animals (particularly the family dogs that appear in so many works) was genuine and consistently evident. He seemed to think both about and with them, to work toward understanding the world in tandem with them.”

-article-image.jpg)

Alex Colville, Dog and Groom, 1991

Acrylic polymer emulsion on hardboard, 62.4 x 72 cm, private collection

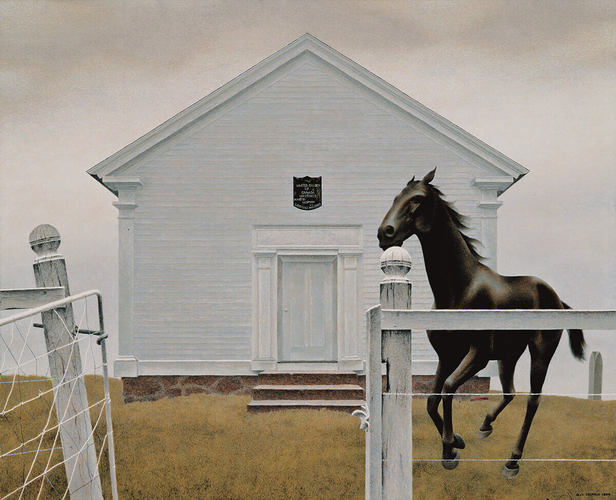

For Colville, so influenced by existentialism and its restless pursuit for the meaning of human nature, animals provide a foil to further his philosophical engagement. As he stated early in his career: “The great task which North American artists have to perform is one of self-realization, but a self-realization much broader and deeper than the purely personal or subjective. The job thus involves answering such questions as, ‘Who are we? What are we like? What do we do?’” Colville posed these questions through the use of symbols: “I am suggesting that primeval myths may be of use to the modern painter.… What I have in mind is the use of material so old, so often used down through the ages, that it has become an integral part of human consciousness.”

Acrylic polymer emulsion on hardboard, 36 x 62.4 cm, Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

Colville’s interest in animals can be tied to the fact that he was a thinker as much as a maker, and his sustained, rigorous approach to creating images is a remarkable legacy. His abiding interest in the nature of being led him to examine the everyday facts of existence. His subject matter is, almost exclusively, the daily life that surrounded him, whether that was in Sackville, Wolfville, or while he was on a sojourn in Santa Cruz or Berlin. For Colville, thinking deeply happens wherever you are, and happens best with familiar things. As art historian Martin Kemp notes, “He is a local painter in the sense that [painter John] Constable was local, creating art that has to draw nourishment from scenes known intimately in order to find a wider truth.”

Acrylic polymer emulsion on Masonite, 80 x 80 cm, private collection

In Colville’s depictions, simple binaries create complex images that resist easy summation. Humans and animals, men and women, humans and machines, the constructed world and the natural environment, are all put into play in his “fictions.” He begins with ideas, and uses familiar objects to express them. According to Colville, “My paintings begin as imaginary drawings, and then at a later point in their development, I make some drawings from life, from reality. It’s interesting that the original conception of one of my paintings, or my prints, always emerges out of my head, rather than from something specifically seen. It’s a sort of conglomeration of experience and observation.”

Acrylic on hardboard, 55.5 x 68.7 cm, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

This Essay is excerpted from Alex Colville: Life & Work by Ray Cronin.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans