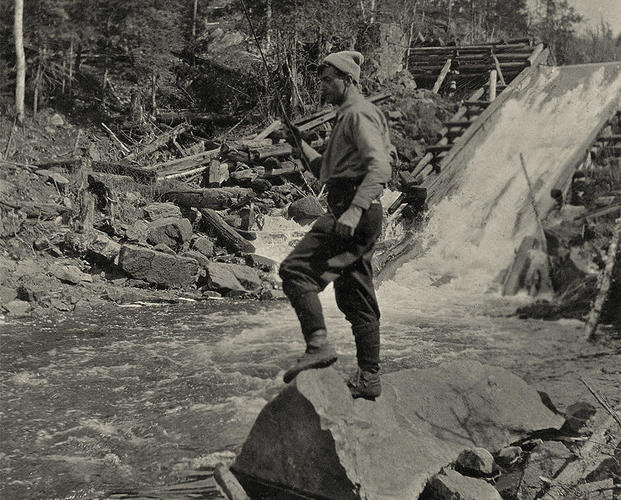

In 1912 Tom Thomson (1877–1917) bought an oil-sketching kit for painting outdoors. With Ben Jackson (1871–1952), a colleague at Grip Limited where they were both commercial artists, he took his first canoe trip early that spring in Algonquin Park, a vast forested recreation area of rivers, lakes, and three luxury hotels that was about three hundred kilometres northeast of Toronto. Teams of loggers had built dams, sluices, and chutes, and much of the park’s acreage of first-growth forests were clear cut. Thomson recorded one of these decaying dams in Old Lumber Dam, Algonquin Park, 1912—a sketch that illustrates his transition from the formalities of commercial art to a more imaginative style of original painting.

Oil on paperboard, 15.5 x 21.3 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Once Thomson left the commercial art room for the backwoods, his painting style loosened up dramatically.

The precision of Drowned Land, 1912, reveals the rapid progress Thomson was making as an artist during that first summer of outdoor painting. The drowned land, perhaps near Lake Scugog or Owen Sound, is the work of enterprising beavers or loggers who, by damming a creek, have drowned a section of meadow and forest at the edge of a lake. The recovering second growth is clearly visible in the background. The painting shows Thomson’s obsessive attention to detail—a constant in his work even as he pursued more complicated ideas and ways of painting his “northern” landscapes.

Oil on paper on plywood, 17.5 x 25.1 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

In the fall Thomson then set out on a two-month canoe trip with another artist friend from Grip, William Broadhead (1888–1960), up the Spanish River and into the Mississagi Forest Reserve (now an Ontario provincial park). There they explored the rough and beautiful terrain north of Manitoulin Island and Georgian Bay. They had two bad spills, however, in which Thomson lost almost all his oil sketches and several rolls of exposed film. Undeterred, and encouraged by the success of the paintings that came out of these early trips, he began to devote his life to making art.

By 1914 he settled into a regular pattern: every spring he headed north to Algonquin Park as early as possible and stayed there as long as he could into the fall. The same year, the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, under director Eric Brown (and advised by board member Lawren Harris [1885–1970]), began to acquire Thomson’s work, first Moonlight, 1913–14, from the Ontario Society of Artists exhibition for $150; then Northern River, 1915, the following year for $500; and a year later Spring Ice, 1915–16, for $300.

Oil on canvas, 52.9 x 77.1 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. This painting was the first of many works by Thomson that the National Gallery purchased, both during his life and later from his estate.

As Thomson’s patron Dr. James MacCallum later recalled, when he first saw Thomson’s sketches from 1912, he recognized their “truthfulness … they made me feel that the North had gripped Thomson,” just as it had gripped him too as a boy. Though his vaunted skills as a canoeist and bushman would be exaggerated by his artist colleagues and admirers after his death, Tom Thomson’s paintings of Algonquin Park and Georgian Bay remain an iconic touchstone in Canadian art.

This Essay is excerpted from Tom Thomson: Life & Work by David P. Silcox.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans