In mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People), Kent Monkman reimagines the history of migration and settlement on Turtle Island, the name many Indigenous people use for the North American continent. Simultaneously, he makes a claim for the relevance of art history. This claim, expressed loudly through the reuse and recontextualization of millennia of Western iconographies, is surprising given that art history itself is responsible for significant cultural erasures. But Monkman’s continued engagement with subjects from antiquity and the Old Masters in the mistikôsiwak diptych resurrects and rewrites the past from an Indigenous perspective, all the while recovering the practice of history painting, and asserting the continued relevance of painting as a medium. This confluence of divergent ideas creates a beautiful, pulsating tension between recognition and revision, defiance and celebration. Exhibited during the 150th anniversary of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Monkman’s work asks the viewer to contemplate, question, and readdress both the histories told in the works of art throughout its galleries and the ongoing role of painting in the production of national narratives and art historical canons.

Revision and Resistance: mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, published by the Art Canada Institute, is available for purchase. Click here to order your copy.

mistikôsiwak is comprised of two monumental-scale paintings measuring 335.3 by 670.6 centimetres. Welcoming the Newcomers presents alternative interpretations of the histories of migration to Turtle Island. Resurgence of the People proposes an optimistic path forward despite the deadly challenges of today (the rising waters due to climate change, for example). Told from an Indigenous perspective, Monkman’s visions of past and future converge in the diptych to provide a simultaneity and circularity of events that recollect the continuous narratives employed by medieval and Renaissance artists for sacred stories. In this sense, Monkman’s panels are at odds with the discrete, linear narratives of history paintings conceived after 1600, with their intentional centring of the West and its colonial project.

While engaging with a variety of Western modes of storytelling, the diptych defies art history’s problematic representations of Indigenous peoples by subverting particular motifs. In Resurgence of the People, Miss Chief as George Washington inspires giggles while she takes a jab at the Western canon of mythologized male leaders. The paintings liberate other figures through the process of quotation—for example, the enslaved African man who appears in shackles in Welcoming the Newcomers reappears in Resurgence of the People as a medical doctor. Monkman’s conflation of time and space in mistikôsiwak creates a liminality in which anything is possible. The practice of continuous narrative was employed by artists throughout Western Europe during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Within these predominantly Christian societies, artists were hired to paint religious stories with an emphasis on the supernatural. This aligned with early-medieval Christian theology, which emphasized the divine kingship of Christ rather than his humanity. Accordingly, realism and relatability were eclipsed by the evocation of a higher power and another world in which the viewer was encouraged to have faith.

Oil on canvas, transferred from wood, each panel: 56.5 × 19.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Right: Kent Monkman, Dude Looks Like a Lady (Of Sorrows), 2017

Acrylic on canvas, 182.9 × 121.9 cm, private collection

Take The Met’s diptych The Crucifixion; Last Judgement, c.1440–41, by Jan van Eyck. On the left, the image of the Crucifixion, the sacrifice that delivers humankind’s salvation, is juxtaposed with the image on the right wherein God is the divine judge. In more recent works, such as Dude Looks Like a Lady (Of Sorrows), 2017, Monkman actively plays within this tradition by appropriating its signs and visual strategies, yet he reformats it for a contemporary audience. One could argue that in his diptych, Monkman challenges or advances Christian diptychs by inspiring faith and hope rather than fear. Resurgence of the People declares that even in peril there is hope, and that fear can be conquered through a return to Indigenous values, community, and collaboration.

In addition to his mastery of medieval and Renaissance iconography, Monkman has a finely tuned understanding of the history of painting, particularly of the literally grand European works of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when painting emerged in full force as the pinnacle of high art. Heroic figures, whether mythological, Christian, or contemporary, and sweeping historical narratives, served propagandistic, didactic, and moralizing purposes. In the wake of the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation, artists were commissioned to create paintings with Biblical subject matter to inspire religious devotion. Artists such as Peter Paul Rubens were tasked with depicting figures and events on a large scale, following guidelines established by the church during the Council of Trent, making works like The Entombment, c.1612. Dominance over the production of art was increasingly held by monarchs such as King Louis XIV whose court controlled the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. In 1667, the Academy began to exhibit works in a public venue known as the Salon, which became instrumental in showcasing the Academy’s approved styles and genres. Throughout the eighteenth century, history painting was promoted as among the highest genres of painting, and Neoclassicism, with its historical figures and stories from the ancient world, served as an aggrandizing counterpart to contemporaneous events.

Oil on canvas, 131.1 × 130.2 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California

Monkman’s Resurgence of the People subverts history painting’s conventional adherence to a linear past with a vision for the future. He draws on the composition of Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851, by Emanuel Leutze, painted seventy-five years after George Washington captained a boat full of troops across the Delaware River. Leutze’s work celebrates Washington as a hero who upholds the ideals of the American Revolution, and captures the moment in which Washington sails to victory at a turning point in the war. He stands astride the wooden boat, weighed down by crew paddling it forward through the icy water—an image of fortitude and impending triumph.

Oil on canvas, 378.5 × 647.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Like Washington, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Monkman’s gender-fluid and time-travelling alter ego, stands strong and tall in contrast to everyone around her. She navigates the waters of a cataclysmic world where Indigenous people offer salvation to those displaced by the same colonial project from which Washington’s so-called victory was born. In Leutze’s painting, the landmass in the upper left corner signifies the ultimate prize. In Welcoming the Newcomers, that same land is visible, and in Resurgence of the People, it is occupied by a small, militarized group who stand in for Washington’s legacy. But that group is surrounded by waters that threaten to submerge them. In fact, Miss Chief leaves them behind, finding power in claiming the boat as a means of transporting Indigenous peoples and their values into the future.

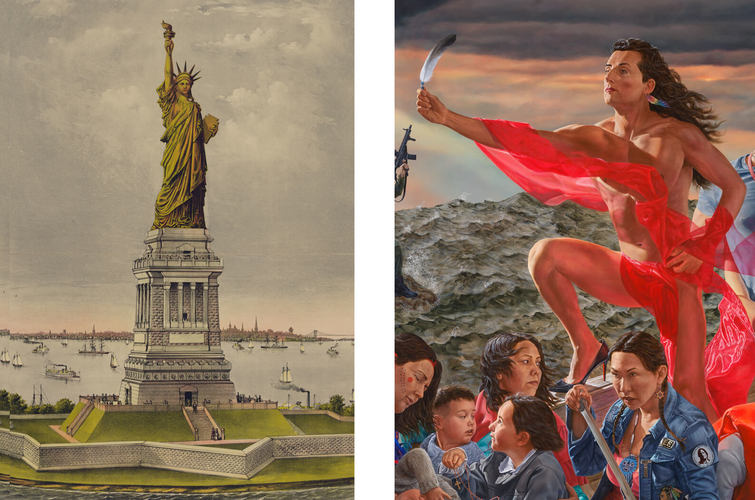

The pose of Miss Chief also invokes the mythical figure of Lady Liberty depicted in the iconic New York City sculpture produced in celebration of the victory of American revolutionaries and abolitionists, and a long-time symbol of hope for arriving settlers. In Resurgence of the People, Miss Chief as Lady Liberty holds an eagle feather instead of a torch. Similarly, Monkman replaces the flag in Leutze’s work with the coup stick, used by Indigenous warriors in the prairies as a sign of bravery in battle. (The coup stick also replaces the hunting spear in Monkman’s figural allusions to classical depictions of Adonis.) Thus, the three symbolic figures who simultaneously pervade Monkman’s painting—Miss Chief, Washington, and Lady Liberty—evoke different notions of victory against adversity. Through Monkman’s quotation, the viewer is asked to consider the meaning and cost of victory: in life, and in posterity, when it is written into history.

Chromolithograph, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Right: Kent Monkman, Resurgence of the People (detail), 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

In Washington Crossing the Delaware, the promise of liberty for all is suggested by the inclusion of African and Indigenous sailors and soldiers, however marginalized in the composition. Of course, Washington himself is now a problematic figure, especially as regards Indigenous peoples and slavery. Leutze’s incorporation of non-white sailors distracts from his painting’s role in nation building through myth. Similarly, the visual reference to Lady Liberty in Monkman’s Resurgence of the People reveals that so-called victory is complex, despite its historical depictions otherwise. Capitalism and democracy have not provided equal opportunity. Monkman’s own symbology questions Western ideas of victory over people and land, which are ultimately out of keeping with an Indigenous perspective. A different and more nuanced notion of victory is offered in Resurgence of the People—a values-based concept of togetherness, family, and reciprocity. The enslaved African figure in Welcoming the Newcomers, for instance, is a doctor in Resurgence of the People, helping a lifeless white man. Monkman shows that resilience and opportunity, combined with good will and love, beget more of the same. The repetition of figures across the diptych, including Miss Chief herself, challenges notions of time: how can two paintings depicting scenes that take place over 150 years apart include the same characters? This repetition across a diptych is an art historical device; in mistikôsiwak, it underlines the parallels and continuums in the historical and contemporary experiences of Indigenous peoples.

Monkman’s deployment of appropriation highlights this very approach in the history of painting. Beginning in the fifteenth century, Italian Renaissance painters studied and revived the qualities of ancient Greek and Roman art. In addition to producing works that adhered to the mathematical proportions developed by ancient Greek sculptors such as Polykleitos, artists of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries placed an emphasis on portraying ideals of harmony, reason, and rationality. While church patronage still grounded many works in religious subject matter, artists increasingly depicted episodes from ancient mythology to comment on contemporary values. Such myths became allegories, as in Sacred and Profane Love, 1514, by Titian, which illustrates the tension between ideal love and carnal desire. In the seventeenth century, Peter Paul Rubens and his peers produced works informed by heroic antique nudes, adapted with a distinctive style to elicit emotion, such as in Rubens’s Massacre of the Innocents, c.1611. In his adaptation of the Old Masters, Monkman similarly conveys messages relevant to a present-day viewer by blending history and allegory.

Oil on canvas, 197.5 × 242.9 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Right: Kent Monkman, Welcoming the Newcomers, 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

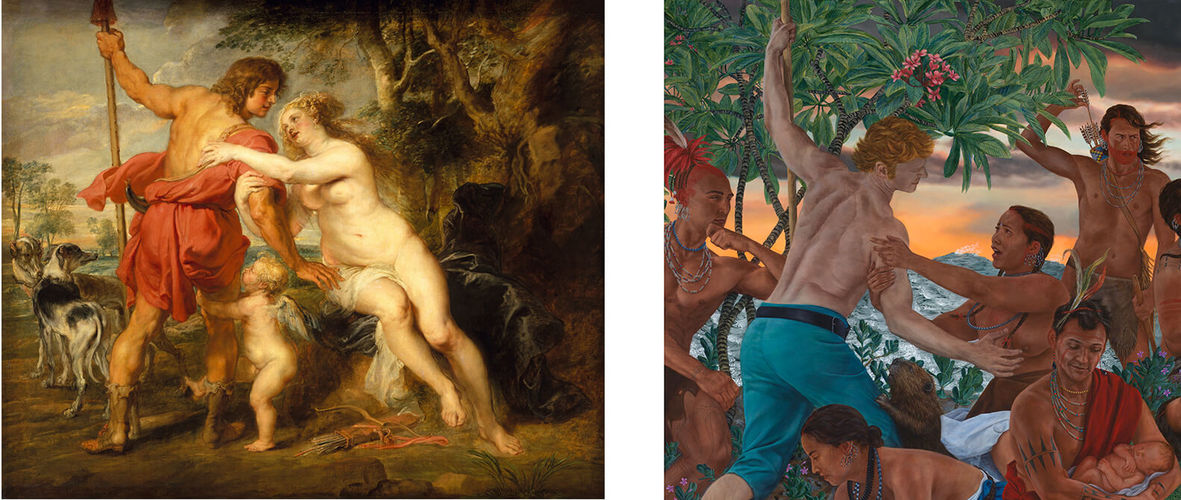

The story of Venus and Adonis reoccurs in both Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People. In the former, Monkman references Rubens’s Venus and Adonis, c.1635, in The Met’s collection. In Ovid’s retelling of the myth in Metamorphoses, Venus warns Adonis of the dangers of the hunt; defying this warning, Adonis is killed by a wild boar. Rubens’s work exemplifies the Baroque tendency to select and depict a major dramatic point within mythic narratives. Adonis twists his body both toward and away from Venus, as she attempts to pull him to her. In Monkman’s Welcoming the Newcomers, Rubens’s mythological subjects are recast: Adonis becomes a European fur trapper and Venus becomes an Indigenous woman who seeks to restrain him. The composition of the figures reflects the original treatment, placing the man-as-hunter in a position of power; however, the hunter twists away from the figure resembling Venus, who offers, one presumes, an equally powerful warning against the consequences of the exploitation of natural resources.

Oil on canvas, 106.7 × 133.4 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Right: Kent Monkman, Resurgence of the People (detail), 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

Rubens most likely looked to Titian’s earlier rendition of Venus and Adonis, 1550s, also in The Met, as both model and inspiration for his depiction. Titian’s subject is Venus offering her warning, but he alters Ovid’s tale. In the Metamorphoses Venus departs on a chariot; in Titian, Adonis takes leave. As in the later Rubens, Venus attempts to hold Adonis back—yet he rebuffs her and pulls away. Figures that reference Titian’s work occupy a central position in both Monkman’s paintings and are depicted in each with the same Indigenous models. In Welcoming the Newcomers he portrays the warning in an Indigenous context in relation to the arrival of Europeans in North America. Through the reoccurrence of these figures in Resurgence of the People he demonstrates the resilience of Indigenous people in both the past and the future.

Indigenous fortitude in the context of Christian imperialism and residential schools is addressed in Resurgence of the People through the grouping of figures at the front of the boat. Referencing François-Joseph Navez’s Massacre of the Innocents, 1824, Monkman’s figures place the subject of King Herod’s mandated murder of first-born children, as told in the Gospel, in the context of the forced separation of Indigenous children from family. Both Navez and Monkman emphasize an intimate moment between mother and child within a larger narrative of tragic loss. Other paintings by Monkman, such as The Scoop, 2018, and The Scream, 2017, show the forcible removal of children from communities by government officials and religious figures, and appear to reference the more explicit and emotive rendition of this Biblical subject in Rubens. Monkman’s practice foregrounds the role that Western visual representation has played in establishing the histories of Turtle Island. His work draws on visual conventions, established in past centuries, that misrepresent Indigenous peoples. In doing so he enacts the kind of recovery and re-presentation of Indigenous figures exemplified by Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People. In earlier pieces such as the performance and video work Casualties of Modernity, 2015, the artist’s commitment to an engagement with and critique of the history of painting is the driving force. For Monkman, the flattening of pictorial space in movements such as Cubism might act as a metaphor for the flattening of Indigenous culture. Within Casualties, he presents Miss Chief as a philanthropist visiting the dying and destitute figures of modern art.

-article-image.jpg)

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 × 320 cm, private collection

If Monkman’s engagement with Western art history both critiques its misrepresentations and locates his own practice within its traditions, the mistikôsiwak diptych extends this practice of recovery into a future where Indigenous values offer hope to those displaced in a world ravaged by centuries of colonialism. The wariness of those who defend their land from Europeans in Welcoming the Newcomers proves pertinent in Resurgence of the People, where weaponized white nationalists defend a rocky outcrop. Within this future of the latter painting, the resilience of Indigenous peoples and the resurgence of their values are essential to the survival of humankind. Here, the sailors in Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware are replaced by Indigenous sailors offering salvation to those cast adrift, with the boat recalling contemporary news-media images of refugees. Simultaneously a celebration and a warning, Resurgence of the People replaces the ideals of the American Revolution with Indigenous values as the driving force for future thriving.

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 × 670.6 cm

The impact of Monkman’s mistikôsiwak is immediate, but the full implications of the narrative unfold through sustained viewing. Disparate sources from Western painting converge and are recontextualized in relation to Indigeneity, sexuality, nationalism, and climate change. The work emphasizes that the allegories of the past are warnings for the future. Time converges to bring historical masterpieces in The Met into dialogue with this future. The gap that occupies the space between the two works in mistikôsiwak is the present: the place from which we must confront where we have been and where we are going.

_______

The author, Sasha Suda, gratefully acknowledges the important research of Brittany Myburgh in preparing this essay as well as her notable insights and generous assistance.

Sasha Suda studied at Princeton University, Williams College and completed her PhD in Art History at New York University. Throughout her career, she has held positions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Art Gallery of Ontario, in her native Toronto. She is now the director and ceo of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, where she seeks to inspire Canadians through the art of the national collection.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix