In 1934 Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) painted Formative Colour Activity, his first semi-abstract painting. He described the experience as transformative: “I painted the canvas …without stopping…I was in an ecstasy.” In 1938, after three years of intensive work in search of a way to express “the essence of life” through what he called his “modalities” or “thought-forms,” Macdonald submitted four fully abstract canvases—Day Break (May Morning) and Rain, Winter, and Chrysanthemum—to the British Columbia Society of Fine Arts show at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Viewers must have been shocked: in Vancouver, many local critics had found the modernism of the Group of Seven beyond their comprehension.

Further east in Toronto, an international exhibition of modern art organized by the Société Anonyme —a New York City group that promoted modernist art—for the Brooklyn Museum had been mounted at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) in 1927 and soundly criticized. That year, an exhibition of what Canadian artist Bertram Brooker called his “world and spirit” paintings was shown at Toronto’s Arts & Letters Club—the first solo exhibition of non-objective and abstract paintings in Canada. Not surprisingly, the critical response was negative. Even in Quebec where modernism would be championed, Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) did not exhibit his first automatiste paintings until 1942.

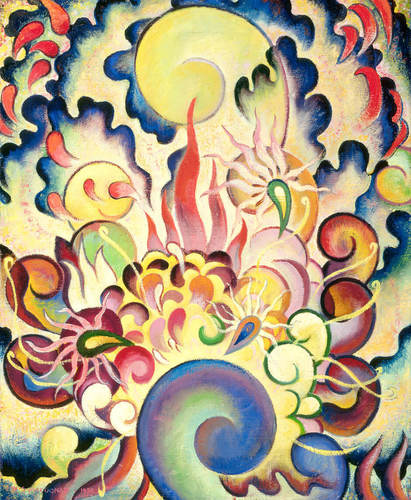

Jock Macdonald, Day Break (May Morning), c.1937

Oil on canvas, 56 x 46 cm, private collection

Thus it came as a surprise to Macdonald when, as the first B.C. artist to exhibit abstract paintings, he received a relatively positive response to his work. In 1938, his semi-abstract painting Pilgrimage (1937) was selected by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa for inclusion in the exhibition A Century of Canadian Art, which the Gallery was organizing for the Tate Gallery in London. A year later, in 1939, Rain and Flight, were both included in the Canadian Group of Painters exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto, while Winter was selected by the NGC for the Exhibition of Canadian Art at the New York World’s Fair.

Over the course of his life Macdonald became a champion of abstract art. After his move to Toronto in 1947, his teaching played a pivotal role in opening the art scene to its possibilities. Many of his former students became leaders in the struggle to assert its importance as an artistic practice. In 1952 Alexandra Luke (1901–1967), who had studied automatic painting with Macdonald while in Banff, organized the Canadian Abstract Exhibition, the first national exhibition dedicated to Canadian abstract painting.

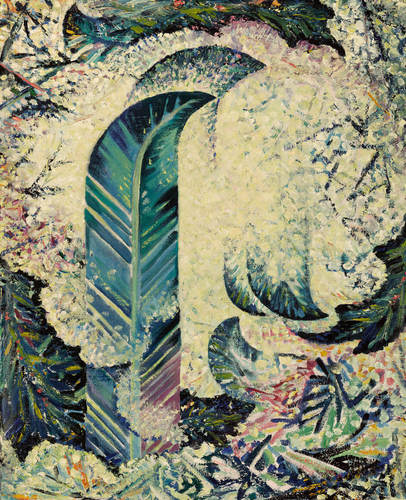

Jock Macdonald, Chrysanthemum, 1938

Oil on canvas, 55 x 45.6 cm, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

Beyond his influence as a teacher, Macdonald also helped to found the Toronto-based Painters Eleven, a group of artists dedicated to abstraction. In 1956 they were invited to exhibit with the Twentieth Annual Exhibition of American Abstract Artists at the Riverside Museum in New York. American critics generally praised their work, and Macdonald’s Twilight Forms, from 1955, was reproduced in Time magazine.

Jock Macdonald, Winter, 1938

Oil on canvas, 56 x 45.9 cm, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Macdonald was upset, however, that the group’s success in New York was virtually ignored by Canadian critics who nevertheless supported the abstract work of his Quebec contemporaries. He complained that when the art historian and curator Jean-René Ostiguy (1925–2016) lectured at the Riverside Museum in conjunction with their exhibition, he “spoke about nothing other than the French Canadian abstract artists … right in the room where Painters XI’s work was exhibited.” In an effort to set the record straight, Macdonald wrote the artist Maxwell Bates (1906–1980), who was writing an article on him, to explain that his own explorations of abstraction predated those of Borduas, though he gave credit to Bertram Brooker and Lawren Harris (1885–1970) as the “first in the field.”

Opening of the 20th Annual Exhibition of American Abstract Artists, New York, 1956

Photograph by Bob Cowans

From left: Jock Macdonald, M.B. Kesserling (vice consul, Canadian consulate), Nettie S. Horch (director, Riverside Museum, New York), Alexandra Luke, Jack Bush, Helen Ronald, William Ronald

By the late 1950s the situation in Toronto, and in English Canada more generally, had changed. Abstract art had begun to take hold. Macdonald’s significance was confirmed when Canadian Art published Bates’ article and the importance of Painters Eleven was acknowledged by the Montreal-based art critic Rodolphe de Repentigny, who wrote on the occasion of their 1957 Montreal exhibition, “scarcely three or four years [after their first exhibition] they were already considered [established] painters.”

Jock Macdonald, All Things Prevail, 1960

Lucite 44 on canvas, 106.7 x 122.1 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

In the last few years of his life, Macdonald was recognized with five solo exhibitions in Toronto—at Hart House in 1957, the Park Gallery in 1958, the Arts & Letters Club in 1959, and the Here and Now Gallery in 1960. He was thrilled when, in 1960, the Art Gallery of Toronto mounted a retrospective exhibition of his work. In the magnificent abstracts of his later years, Macdonald succeeded in his desire to transcend the material to find an expression of the spiritual. He wrote to Max Bates, “The critics spoke very highly of my work, the artists have been quite appreciative and the public thoroughly interested.”

This Essay is excerpted from Jock Macdonald: Life & Work by Joyce Zemans.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix