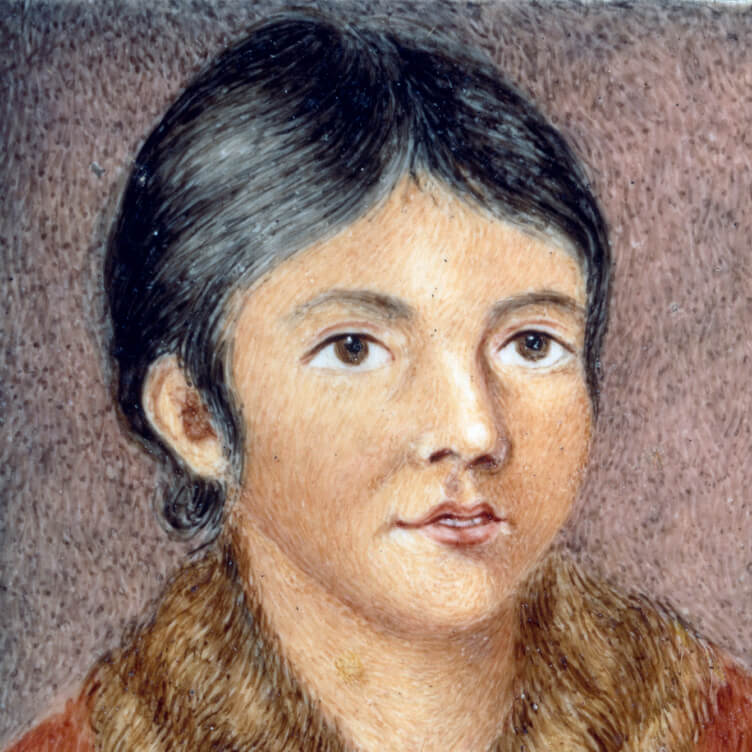

The four children of Huron-Wendat artist Zacharie Vincent (1815–1886) were born in the mid-nineteenth century, when his community of Jeune-Lorette was experiencing a regeneration, culturally and demographically, thanks to the prosperity of the village’s artisanal industries. This painting can be understood as a conscious response to those who had predicted the disappearance of the Hurons. Vincent portrays himself with his eldest son, Cyprien, clearly offering evidence that his own line was in no danger of dying out.

Zacharie Vincent, Zacharie Vincent and His Son Cyprien, c.1851

Oil on canvas, 48.5 x 41.2 cm, Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

The portrait presents certain problems of scale: the boy is extremely small, and his arms are disproportionate to the rest of his body. This awkwardness seems to be intentional, the result of the artist’s decision to use different styles of representation: one is marked by the realism inherent in a portrait of a specific subject, taken from life; in the other, symbol transcends reality. The father’s face, seen as if in close-up, draws the viewer’s attention not only to the details of costume and ornament but also to the face and eyes of the subjects. The metal ornaments (the medal and the armband) present a muted, opaque surface, without reflections, allowing the artist to depart from strict realism while effectively capturing the attention of the viewer.

Since the Renaissance, self-portraits have been used by artists to mark significant stages in their lives. In the early years of his career Vincent used the genre to define his identity, both professional and individual, and to document his status as a father and an artist.

This Spotlight is excerpted from Zacharie Vincent: Life & Work by Louise Vigneault.

Pyramid Scheme

Pyramid Scheme

Transportive Trunks

Transportive Trunks

The Military Mate

The Military Mate

Looking Up on the World

Looking Up on the World

Vessel of Despair

Vessel of Despair

Layers of Meaning

Layers of Meaning

In Parallel to Nature

In Parallel to Nature

Wheel of Fortune

Wheel of Fortune

Paintings after emotional states

Paintings after emotional states

Garden of Delight

Garden of Delight

Stitching the Archives

Stitching the Archives

A Working-Class Hero

A Working-Class Hero

Imagining Entangled Futures

Imagining Entangled Futures

Bridging Far and Near

Bridging Far and Near

Soft Power

Soft Power

Imagining Emancipation

Imagining Emancipation

A Priceless Portrait

A Priceless Portrait

Meditation in Monochrome

Meditation in Monochrome

Making His Mark

Making His Mark

Honour and Sacrifice

Honour and Sacrifice