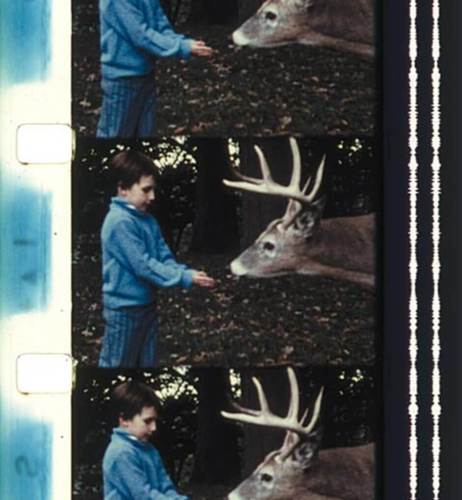

For Jack Chambers (1931–1978), films provided the temporal dimension that he could never fully achieve in painting. Olga and Mary Visiting, 1964–65, and his silver paintings of 1966–67 could only point in this direction. While cinema inevitably moves ahead in our “real” time of viewing, Chambers is never content with a simple, linear narrative. The Hart of London, his longest and most ambitious completed film, plays with time in myriad ways.

16mm black and white and colour film, sound, 79 min., Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

For the pursuit and eventual capture of the deer that gives the film its punning title, Chambers employed found news footage from 1954, liberally borrowed from the archives of CFPL-TV in London, Ontario. He also deployed film he shot in Spain for the pivotal abattoir scene. In London he shot footage for the delicate sequence near the conclusion in which his sons feed domesticated deer while their mother, Olga, whispers, “You have to be very careful” and for the transcendent closing sequences of water and sky. Olga’s voice-over is not only poignant, given the fragility of the young children and the deer, but also surprising, as most of the sound in The Hart of London refuses to advance or even connect with the narrative.

Hart is an endlessly layered tour de force. It explores life and death, the sense of place and personal displacement, and the intricate aesthetics of representation. It is a personal and spiritual film, marked inevitably by Chambers’s knowledge that he had leukemia. The American avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage (1933–2003) said of Hart, “If I named the five greatest films [ever made], this has got to be one of them.” Even this high praise falls short of hyperbole. The Hart of London is at the centre of Chambers’s extraordinary achievement.

This Spotlight is excerpted from Jack Chambers: Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham.

Pyramid Scheme

Pyramid Scheme

Transportive Trunks

Transportive Trunks

The Military Mate

The Military Mate

Looking Up on the World

Looking Up on the World

Vessel of Despair

Vessel of Despair

Layers of Meaning

Layers of Meaning

In Parallel to Nature

In Parallel to Nature

Wheel of Fortune

Wheel of Fortune

Paintings after emotional states

Paintings after emotional states

Garden of Delight

Garden of Delight

Stitching the Archives

Stitching the Archives

A Working-Class Hero

A Working-Class Hero

Imagining Entangled Futures

Imagining Entangled Futures

Bridging Far and Near

Bridging Far and Near

Soft Power

Soft Power

Imagining Emancipation

Imagining Emancipation

A Priceless Portrait

A Priceless Portrait

Meditation in Monochrome

Meditation in Monochrome

Making His Mark

Making His Mark

Honour and Sacrifice

Honour and Sacrifice