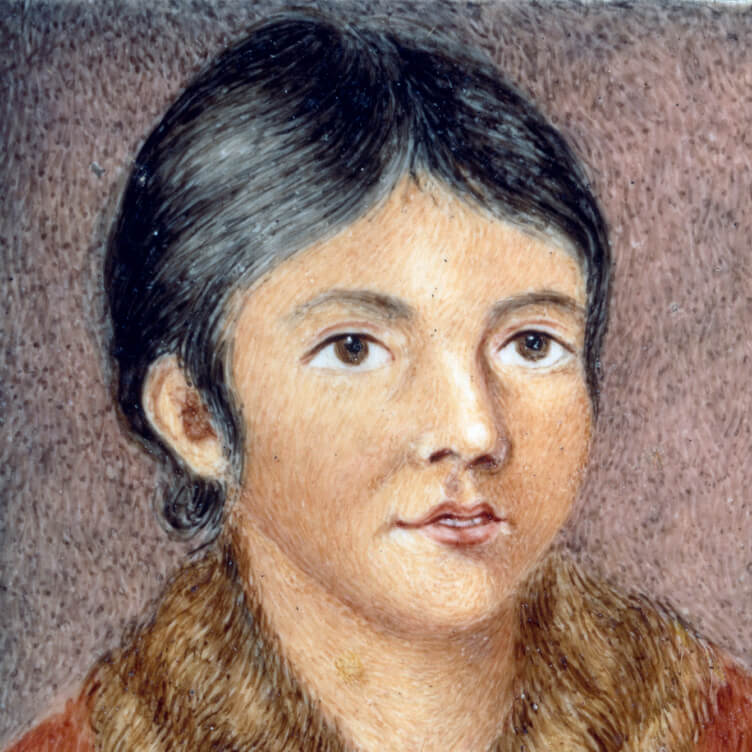

Sunny September, 1913, by the Canadian Impressionist Helen McNicoll (1879–1915), is a pleasant scene of a woman and children who appear to be sightseeing. Their clean white dresses suggest they are not local but middle-class tourists enjoying the view. In the Edwardian period, tourism was a relatively recent form of leisure, and daytripping scenes were popular subjects for French and American Impressionists. McNicoll’s beach scenes join those of artists such as Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Childe Hassam (1859–1935) in portraying a modern theme. Somewhat unusually, McNicoll’s subject in Sunny September isn’t the undisturbed natural vista traditionally sought by sightseers but the tourists themselves in the act of looking.

Helen McNicoll, Sunny September, 1913

Oil on canvas, 92 x 107.5 cm, Collection Pierre Lassonde

Sunny September reveals McNicoll’s skill in representing sunlight. In this image of three figures standing on a grassy hill looking out over the beach, the artist represents the effects of sunshine on a variety of surfaces: the shadows accenting bright white dresses, the sunburnt cheeks of the main figure, the alternately green-dappled and yellow-bleached grasses, and the hazy meeting of blue sky and sea.

As in many of McNicoll’s paintings, the other senses, of touch, smell, and sound, are also evoked here: the viewer imagines the warmth of the sun, the smell of the ocean, and the rustling sound of the long grasses. Kristina Huneault has suggested that this frequent feature of McNicoll’s work was a result, perhaps, of her loss of hearing as a child.

This Spotlight is excerpted from Helen McNicoll: Life & Work by Samantha Burton.

Pyramid Scheme

Pyramid Scheme

Transportive Trunks

Transportive Trunks

The Military Mate

The Military Mate

Looking Up on the World

Looking Up on the World

Vessel of Despair

Vessel of Despair

Layers of Meaning

Layers of Meaning

In Parallel to Nature

In Parallel to Nature

Wheel of Fortune

Wheel of Fortune

Paintings after emotional states

Paintings after emotional states

Garden of Delight

Garden of Delight

Stitching the Archives

Stitching the Archives

A Working-Class Hero

A Working-Class Hero

Imagining Entangled Futures

Imagining Entangled Futures

Bridging Far and Near

Bridging Far and Near

Soft Power

Soft Power

Imagining Emancipation

Imagining Emancipation

A Priceless Portrait

A Priceless Portrait

Meditation in Monochrome

Meditation in Monochrome

Making His Mark

Making His Mark

Honour and Sacrifice

Honour and Sacrifice