Gaucher produced highly ordered, geometrical, and flat images that pushed the boundaries of Canadian painting to explore and question the experience of colour and time. The hard-edge painting technique is a necessary component to the experience of Gaucher’s paintings as events in time. Music was a fundamental influence on his development, and he often used musical titles to suggest analogies to the rhythmic movements of his compositions.

Printmaking

In the early 1960s Gaucher was known as a printmaker, having quickly established himself as a prize-winning participant in international exhibitions. His prints of the late 1950s and early 1960s are remarkable for their technical innovations, demonstrating extensive experimentation with relief and lamination. Like the paint-heavy small works by Guido Molinari (1933–2004) and Claude Tousignant (b. 1932) from 1954–55, Gaucher’s prints share a delight in material physicality.

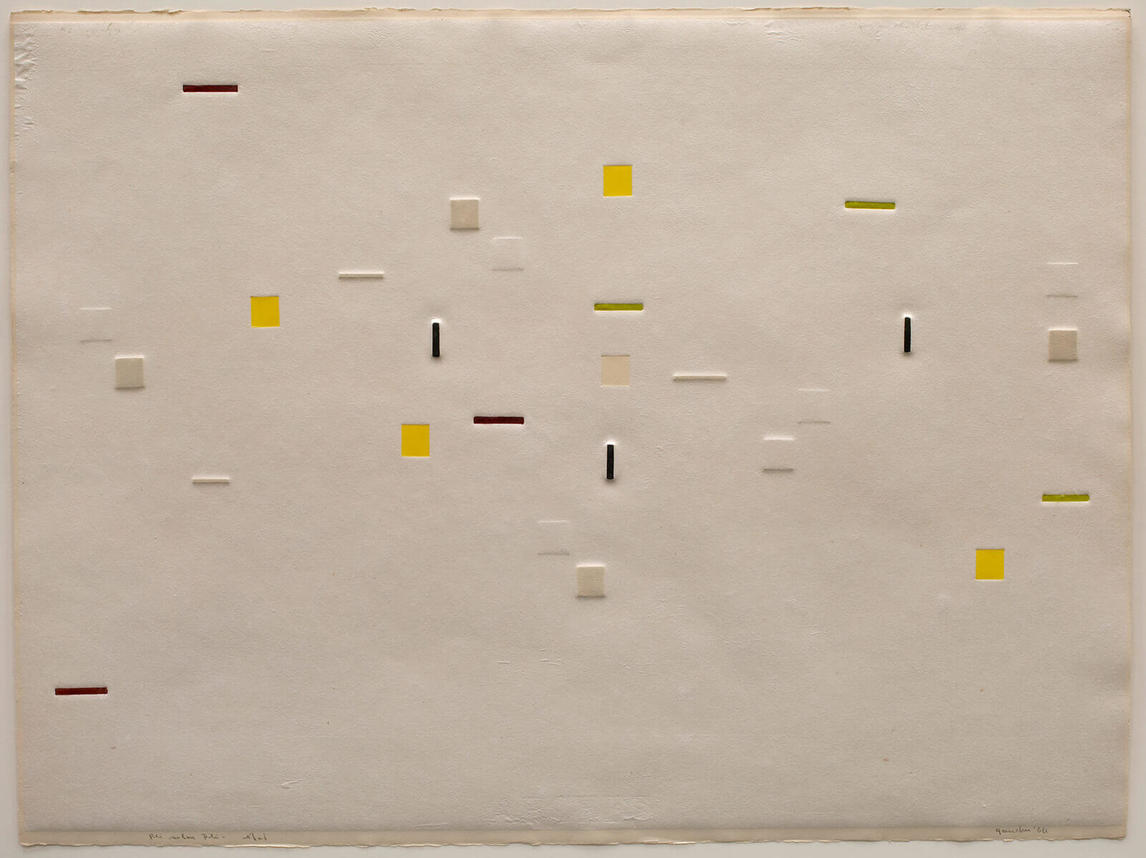

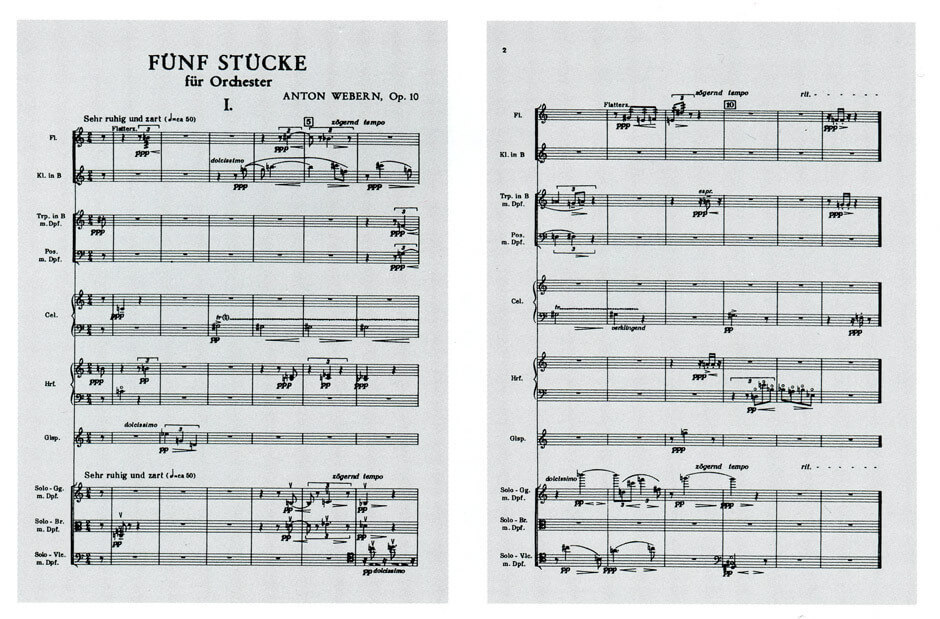

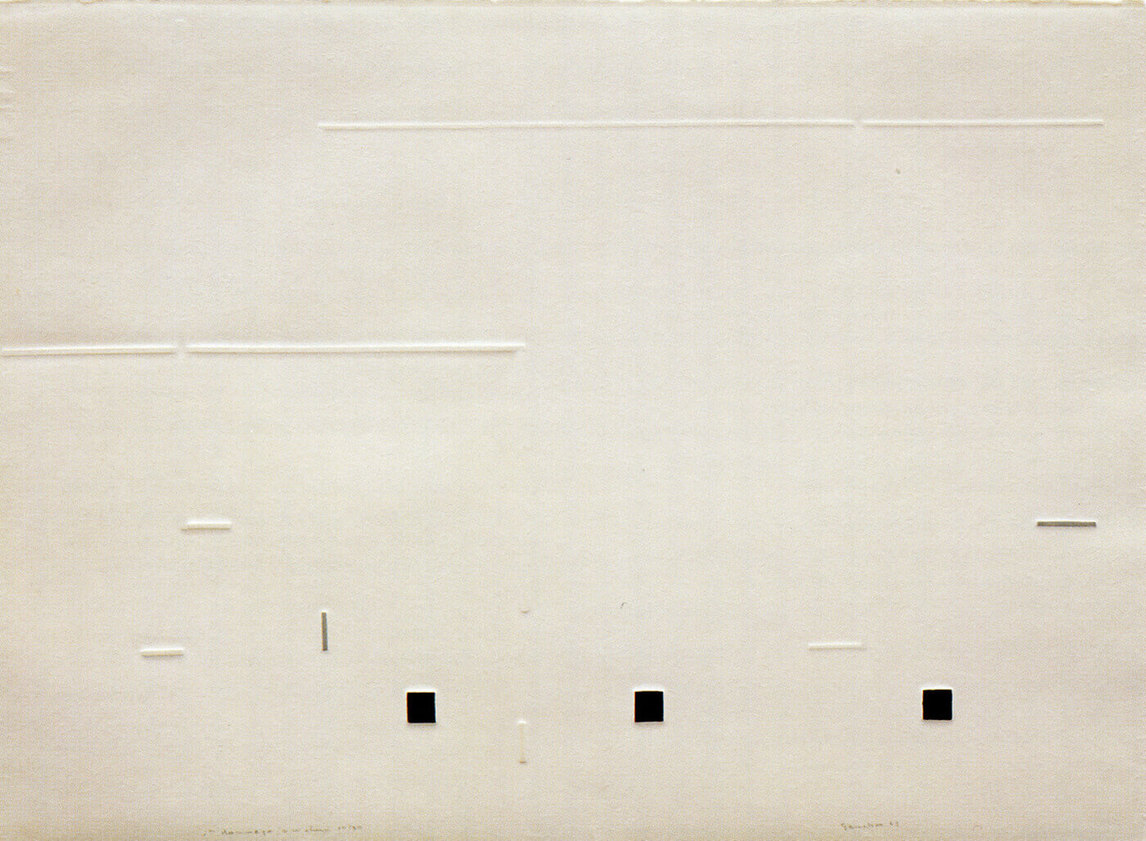

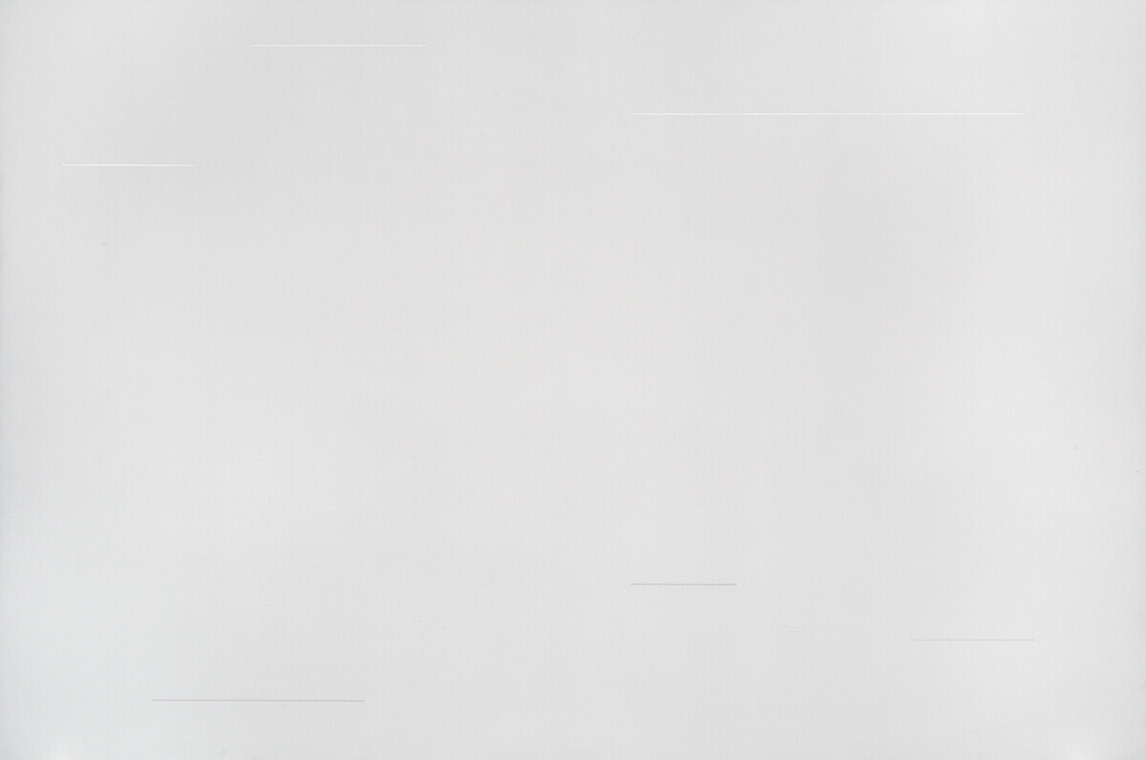

In Sgana, 1962, Gaucher inserted a single straight line, and then other rectangular subdivisions. Soon he had adopted a full-fledged geometry, staking out a place in the Plasticien ambience with his seminal suite of prints In Homage to Webern, 1963, and the other relief prints related to it, until by 1964 and 1965, he made painting his principal focus.

These prints were crucial to Gaucher’s evolution into a Plasticien painter, or rather, to his birth as a post-Plasticien one. They dispense with quasi-biomorphic shapes, turning to a system of pure notations: lines, squares, and dashes, sometimes inkless, sometimes black and grey, eventually introducing colours in Yellow Fugue (Fugue jaune), 1963, and Fold upon Fold (Pli selon pli), 1964. Gaucher would later call them “signals,” which bounce the eye from one point of focus to another. The prints look rigorously structured but are free and spontaneous, their formal order at odds with the vivacity of their effect.

Hard-Edge Painting

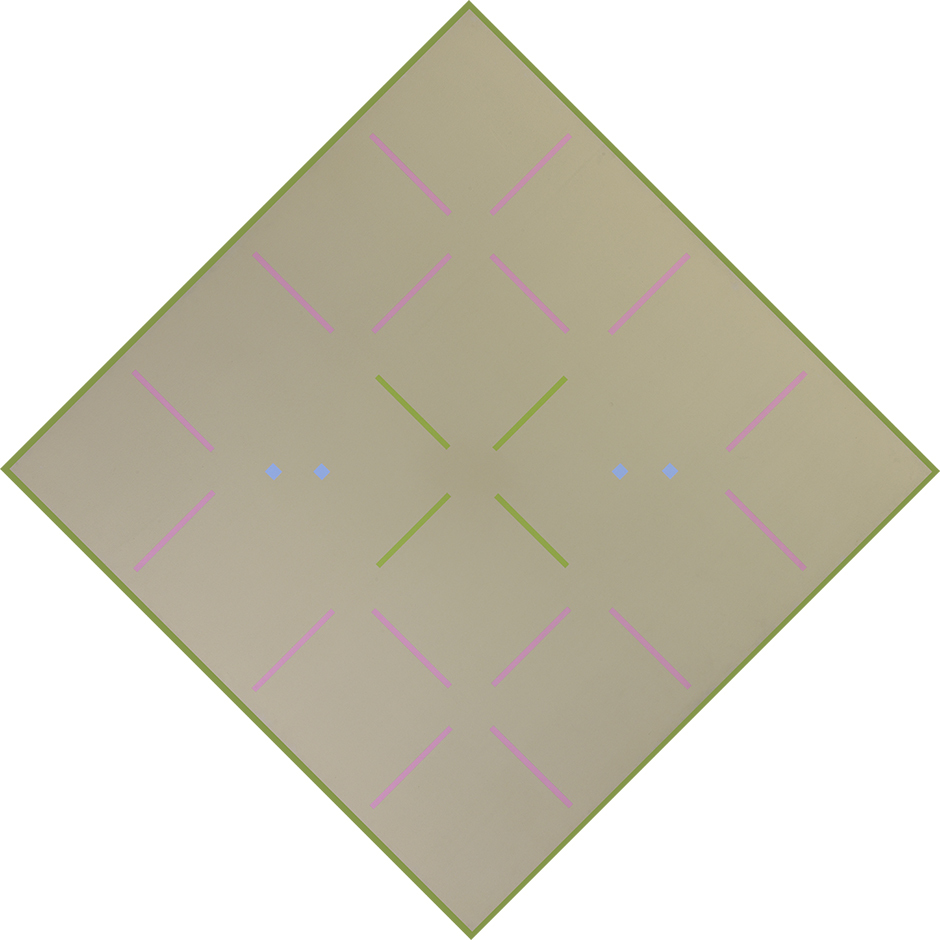

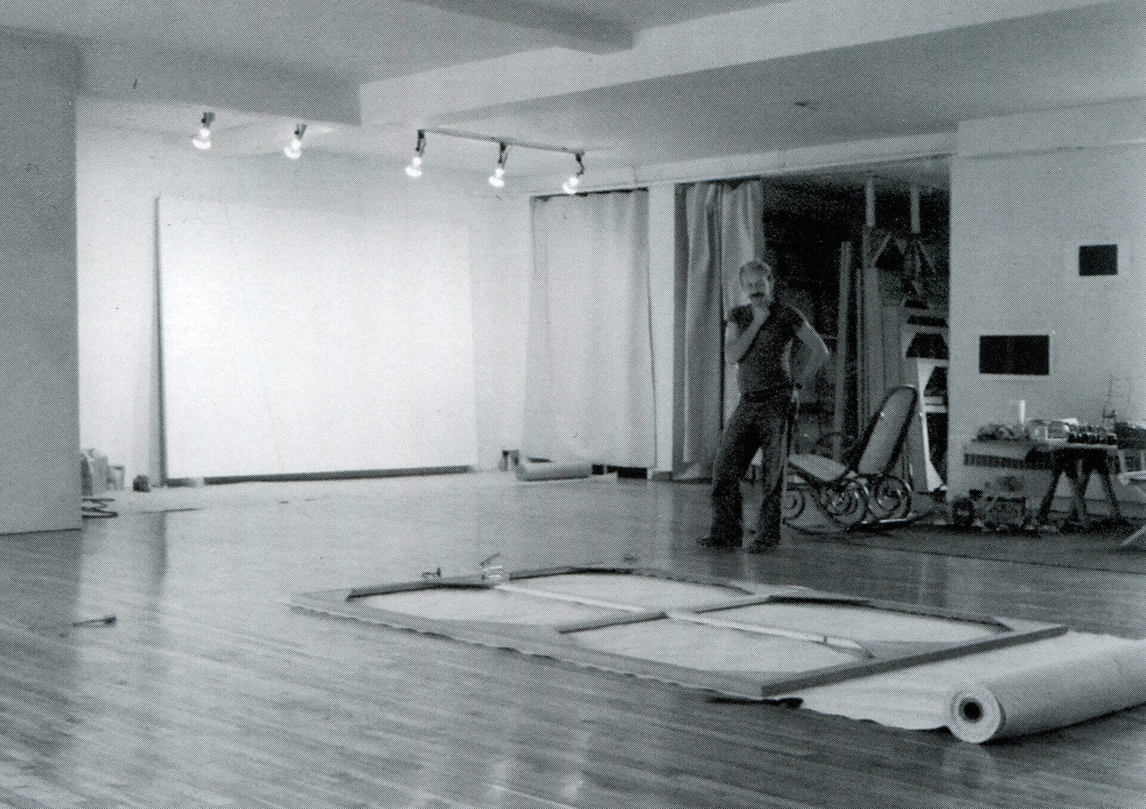

Like his fellow Montreal artists Guido Molinari (1933–2004) and Claude Tousignant (b. 1932), Gaucher applied his paint with a roller on primed canvases, using masking tape to keep the edges straight and crisp. The point was to shut out traditional illusionism entirely, allowing not even the slightest implication of space behind the painting’s surface, even that shallow poetic space opened up by the soft edges of the staining techniques of Post-Painterly Abstraction.

In the mid-1960s Gaucher concluded that a painting could no longer be a window onto, or a picture into, another imaginary world. Instead it should exist more like a literal object in this world, whose surface was articulated with a number of colours organized geometrically as in the Square Dances series. These colours were carefully calibrated so that they would interact optically in the eye of the viewer, and their geometric relations let them play a rhythmic dance across the painting’s surface. The visual activity would occur then, not in some space inside the painting, but in front of it, in an animated space that simultaneously embraces the painting and the viewer who sets it in motion.

To establish such a space necessitated hard edges, impersonal surfaces, and a certain order and symmetry. Equally important, because our viewing experience of a Gaucher painting is never static, is never resolved, but is always caught up in a recurring series of rhythmic movements, the painting ceases to be a fixed thing, our experience with it more like participating in an event in time.

Gaucher’s hard-edge technique is key to our experience of the paintings as events in time. Music was a fundamental influence on his development, and he often used musical titles (Fugue, Square Dance, Raga) to suggest analogies to the rhythmic movements of his compositions.

Gaucher and Time

Time as a condition of looking at a painting was a critical issue in the mid-1960s. In his still remarkable 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood,” Michael Fried requires modernist painting—meaning Post-Painterly Abstraction—to preserve a condition that he calls “presentness.” He argues that you can “experience the work in all its depth and fullness” in a brief moment, since all that you need to know is in front of your eyes. In contrast, Fried describes the experience of Minimalist art as occurring within a limitless flow of time.

The same admonition would, by extension, apply to painting like Gaucher’s that, at least in the 1960s, changes under our eyes and has no fixed moment of resolution. Asked by Canadian Art magazine in 1965 to explain his work, Gaucher produced a text whose gist would have been familiar to his fellow post-Plasticiens. Where Guido Molinari (1933–2004) explained his work with reference to the American philosopher Alfred Korzybski’s “principle of non-identity” and Claude Tousignant (b. 1932) spoke of “non-determination,” Gaucher declared his paintings to be about the “relations of indetermination.”

Gaucher and Music

Music had a deep influence on Gaucher. In an interview from 1996, he recalled, “It was only in music that I came to understand what a profound aesthetic experience really was. I heard concerts that marked me, that opened my ears and eyes. A very strong sensorial experience. Then in my work, I sought to recreate this experience which made me forget time, space, physicality.” Throughout his life he retained a deep commitment to jazz, Indian music, and contemporary classical music.

His musical indebtedness is reflected in his works’ titles: the In Homage to Webern prints, 1963; Fold upon Fold, 1964, borrowed from a 1957 Pierre Boulez composition; Blue Raga and Alap from the mid-1960s, taken from Indian music; Silences, 1966; and Transitions, 1967. He described rhythm, in the context of both life and art, as the basis of aesthetic experience.

This is subject matter most richly discussed in relation to the In Homage to Webern prints, whose conception dated back to a concert of music by Pierre Boulez, Edgard Varèse, and Anton Webern that Gaucher attended during his first visit to Paris in 1962. It was Webern’s music that most profoundly disturbed him and challenged the basic preconceptions that heretofore had driven his artistic expression. As he recalled: “The music seemed to send little cells of sound into space, where they expanded and took on a whole new quality and dimension of their own.”

The experience provoked a crisis and an intense period of work. For a long time he experimented with drawings until he arrived at the dynamic formal solution of the Webern prints in which the composer’s “cells of sound” found their visual equivalents in the “signals,” the system of pure notations of lines, squares, and dashes that he disperses across his paper sheets. It is not that Gaucher is illustrating music that he had heard, and the title of his prints do not reference any specific work of the composer. It is rather as if in his mind’s eye Gaucher had envisaged visual equivalents for Webern’s aural sensations as they dispersed themselves in the space of hearing.

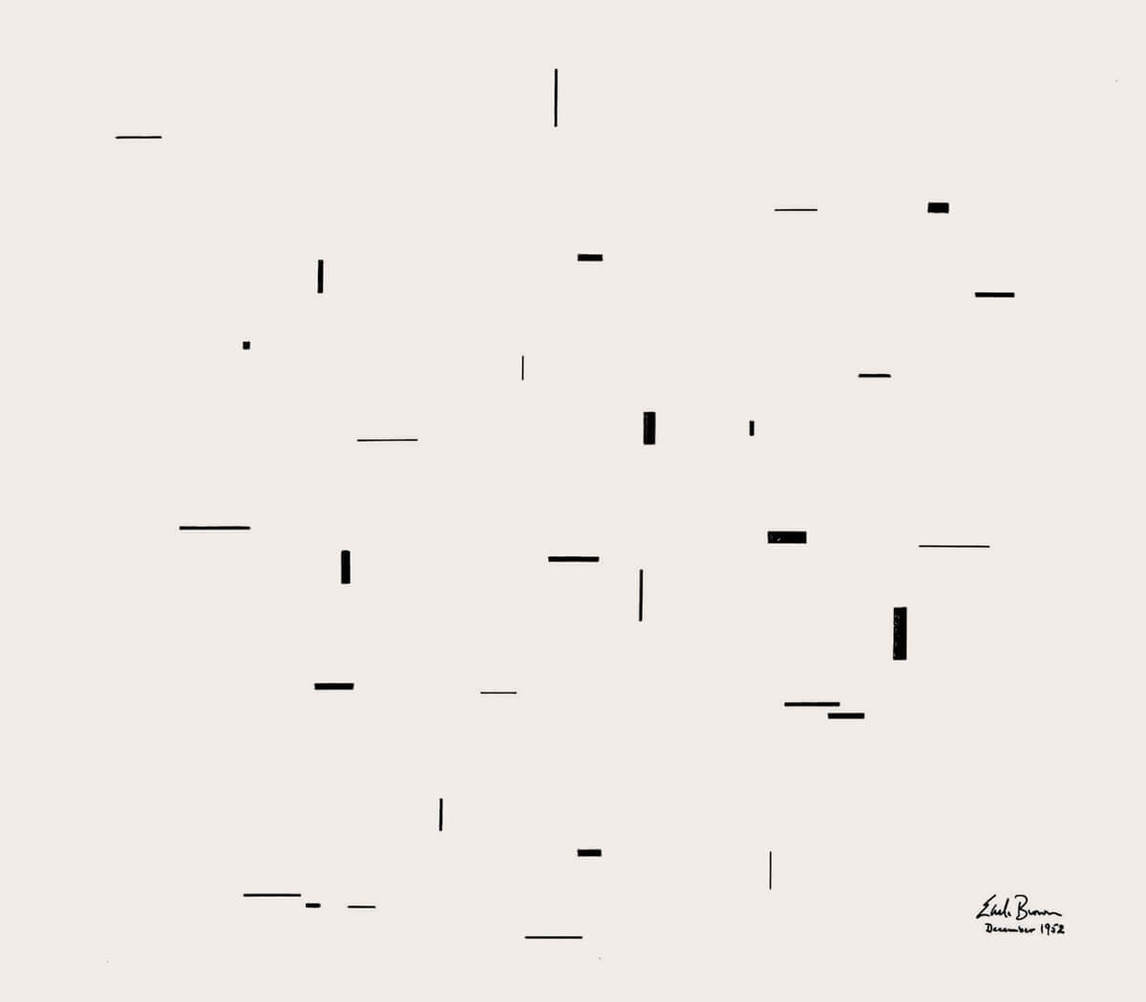

Also of note are the close visual analogies between Gaucher’s prints and the graphic score for “December 1952,” by the American composer Earle Brown. Brown invented and used various innovative musical notations: his score for “December 1952” is made up entirely of points and horizontal and vertical dashes of different shapes and sizes, separated in space and spread out over the page. It is not known whether Gaucher was familiar with Brown’s score, but he would have been aware of the general influence of the avant-garde composer John Cage, out of which Brown’s work had grown.

Brown’s score shares the Webern prints’ non-centred dispersal of their symbols in such a way, as the musicologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez describes it, that it “invites the performer to play the different elements in random succession and therefore escape from the linear constraints of a ‘normal’ score.” In an analogous way Gaucher’s viewer randomly enters the open compositions of the Webern prints at will and manoeuvres through their structures along non-prescribed routes, in effect improvising as he goes.

Gaucher had also begun to listen to Indian music sometime around the beginning of the 1960s, in conjunction with reading Indian philosophy. He described the Indian raga as another of the strongest musical experiences he had experienced, valuing it for its constructive discipline. In the concerts of Ali Akbar Khan, his favourite performer, however, the results became “free and creative,” until listening intensified into an “ecstatic experience.”

Gaucher, nevertheless, despite his passion for music, became cautionary when people started to describe him as “a musical painter.” He had originally used musical titles because, as he said, “I felt they were more abstract, and it backfired.” By 1967, therefore, he largely abandoned titles, substituting letter and number combinations, such as JN-J1 68 G-1, 1968, that would be meaningless except to himself, for whom they served as codes to identify the colours he had used in each painting, for reference, in case of future repair work.

In 1968, as a guest artist, he joined the graduate program in electronic music at McGill University, intrigued by, among other things, the electronic equipment that could read drawings and translate them into music, and vice versa. But he found the exercises finally meaningless, reinforcing his dictum that “true art should be a purely visual language, just as music is a purely auditive [sic] language…. Art must speak only to the eyes, and to nothing else, to reach the soul.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements