Gaucher’s work played a crucial role among the Plasticien painters, who in the 1960s made Montreal a centre for hard-edge and colour-field painting. Plasticien painting emerged at the same time as Post-Painterly Abstraction in Toronto and in the United States, and the two movements shared important stylistic characteristics. At the same time, Gaucher and his fellow Montrealers were fundamentally different, both in how they understood pictorial space and in the way they engaged with the viewer.

Gaucher and the Post-Plasticiens

When Gaucher’s painting came to maturity in the mid-1960s he was a relative latecomer to the Plasticien movement in Montreal. The Plasticiens, however, had an evolving history that is usefully divided into three phases. It is at the beginning of the last of these, during what might be called the post-Plasticien phase, that Gaucher enters the story.

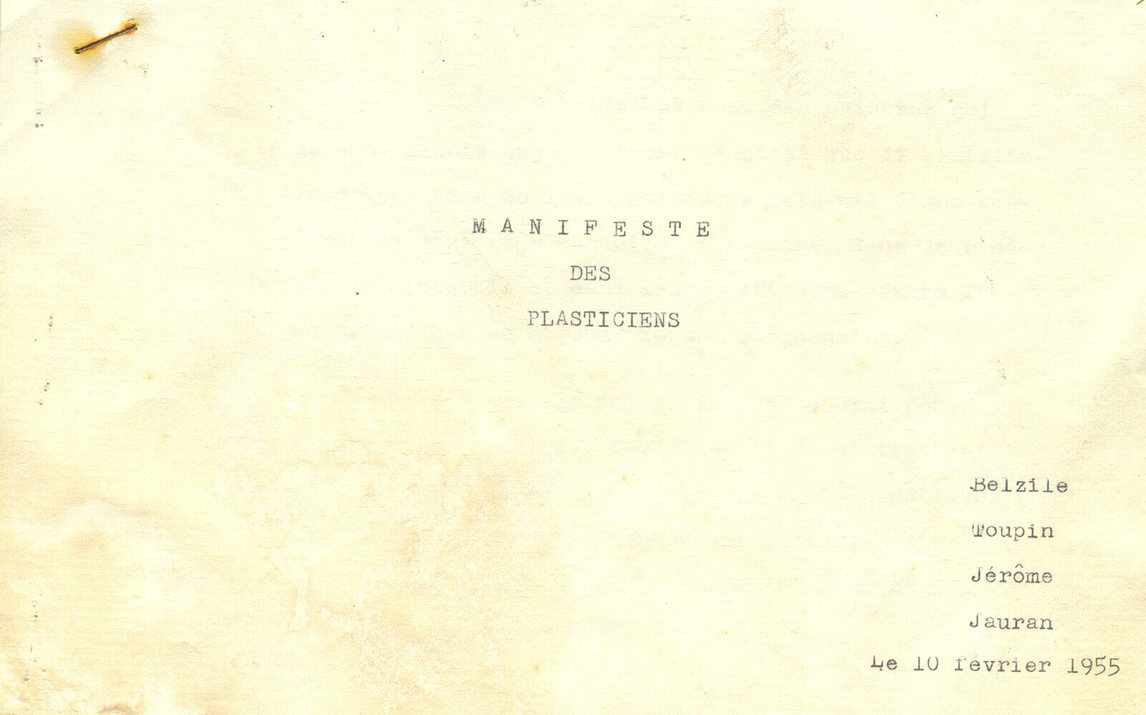

The Plasticien movement initially gained attention in 1955 when a group of young painters—Jauran (Rodolphe de Repentigny) (1928–1959), Louis Belzile (b. 1929), Jean-Paul Jérôme (1928–2004), and Fernand Toupin (1930–2009)—showed together and published their Plasticien manifesto. These four artists, the “first” Plasticiens, sought to rebuff the spontaneous techniques of their Automatiste predecessors, challenging the free brushwork and gestural style with a more impersonal geometry. In 1956, however, the so-called second Plasticiens, Guido Molinari (1933–2004) and Claude Tousignant (b. 1932), accused the first Plasticiens of being timid, old-fashioned, and European in their outlook and challenged them with an even more severe, flatter, and larger-scaled geometric clarity.

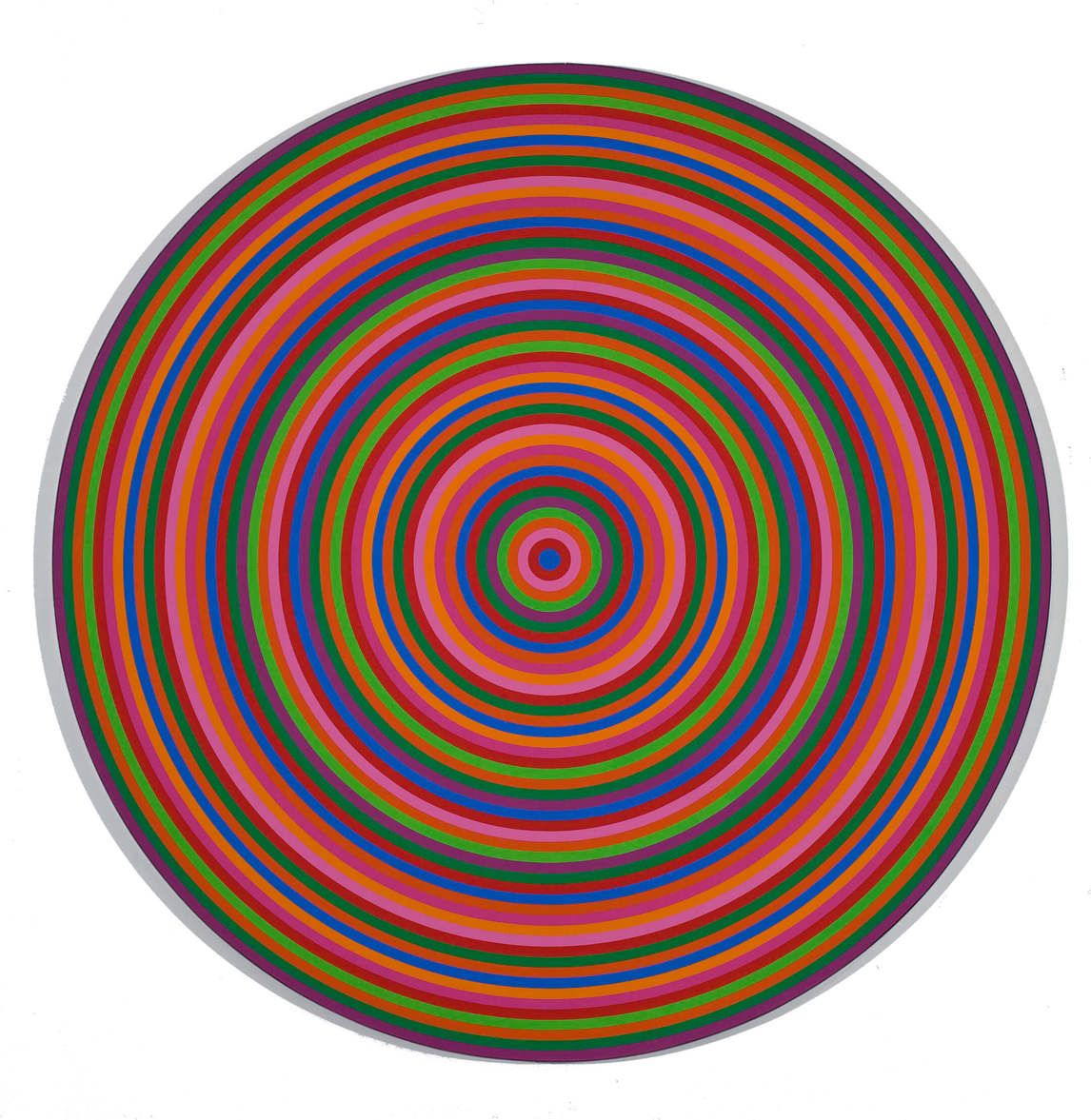

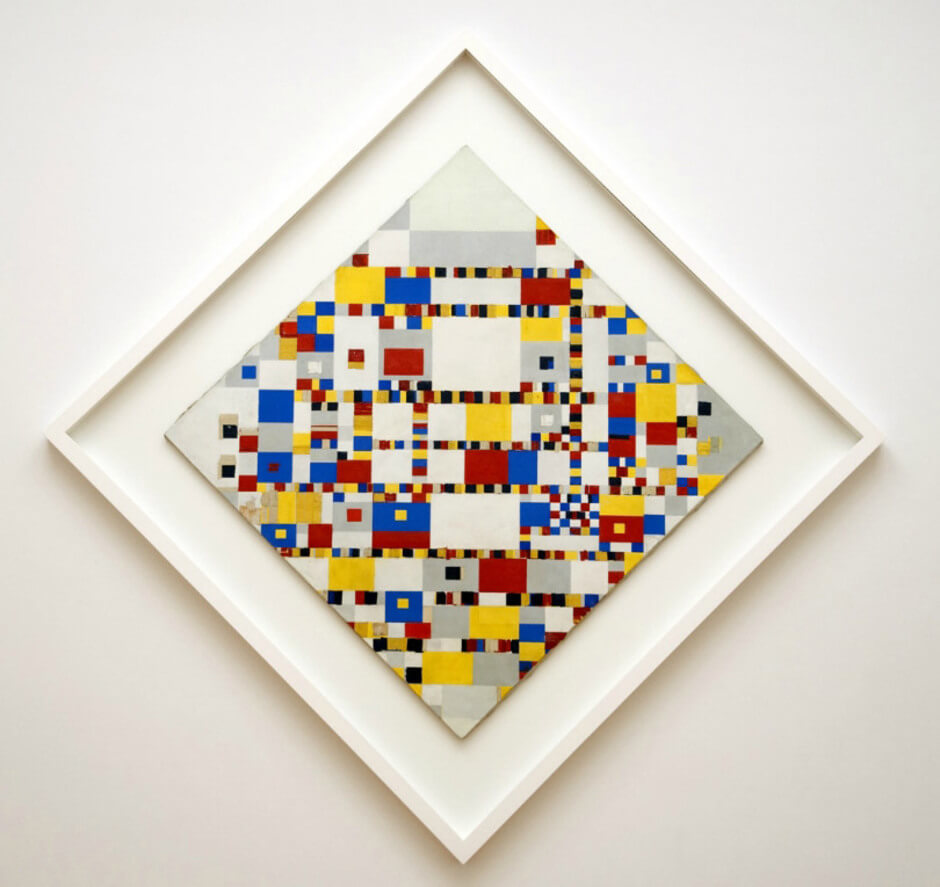

The second Plasticiens grew to embrace other geometric painters, including some of the first Plasticiens. But their hard-edge geometry, as they practised it during the rest of the 1950s, also retained something of a retrospective European character. In the tradition of the work of Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), they built their paintings by balancing one structural part against another in pursuit of compositional balance and equilibrium. By the early 1960s, however, Molinari, with his Stripe Paintings, and Tousignant, with his targets, fully came into their own, evolving their work into the post-Plasticien phase. With such paintings they overthrew the formal compositional principles of the 1950s—the quest for intrinsic order and balance—to pursue new colour-based dynamic ways of actively engaging the viewer.

It is within the stylistic developments of the post-Plasticien phase as it evolved in the early 1960s that Gaucher’s work must be understood. For personal reasons, Gaucher separated himself from Molinari and Tousignant. He entered the Montreal scene, fully born as a post-Plasticien, with his 1963 series of prints In Homage to Webern, followed two years later by his painting series Square Dances.

Gaucher and Post-Painterly Abstraction

Gaucher and his fellow Montreal post-Plasticiens emerged in parallel to Post-Painterly Abstraction, the latter a term coined by the American critic Clement Greenberg in the early 1960s to describe the new abstract painting by artists inspired by Henri Matisse (1869–1954), such as Morris Louis (1912–1962) and Kenneth Noland (1924–2010) in Washington, Jack Bush (1909–1977) in Toronto, and Kenneth Lochhead (1926–2006) in Regina. The artists of both movements were in practice “post-painterly”—that is, they rejected thick paint and personal gesture in favour of a thinner, more anonymous paint application.

Post-Painterly Abstract painters so thinned their paint that they stained it into the weave of their raw canvases, letting colours bleed and leaving edges soft. The Montrealers, in contrast, applied their colour planes with a roller onto primed canvases, keeping their edges straight, crisp, and hard. The aesthetic criteria that Greenberg applied when selecting the artists for his 1964 exhibition Post Painterly Abstraction, which opened in Los Angeles and closed in Toronto, in effect excluded the work of the Montreal painters.

Even so, the Montreal post-Plasticiens had already found their independent voices by the time that hard-edge and colour-field painting in general became the subject of international, if largely New York–based, debates. These inevitably centred around the critical issues proposed by Greenberg’s 1964 exhibition and William Seitz’s 1965 optical art exhibition The Responsive Eye, at the Museum of Modern Art.

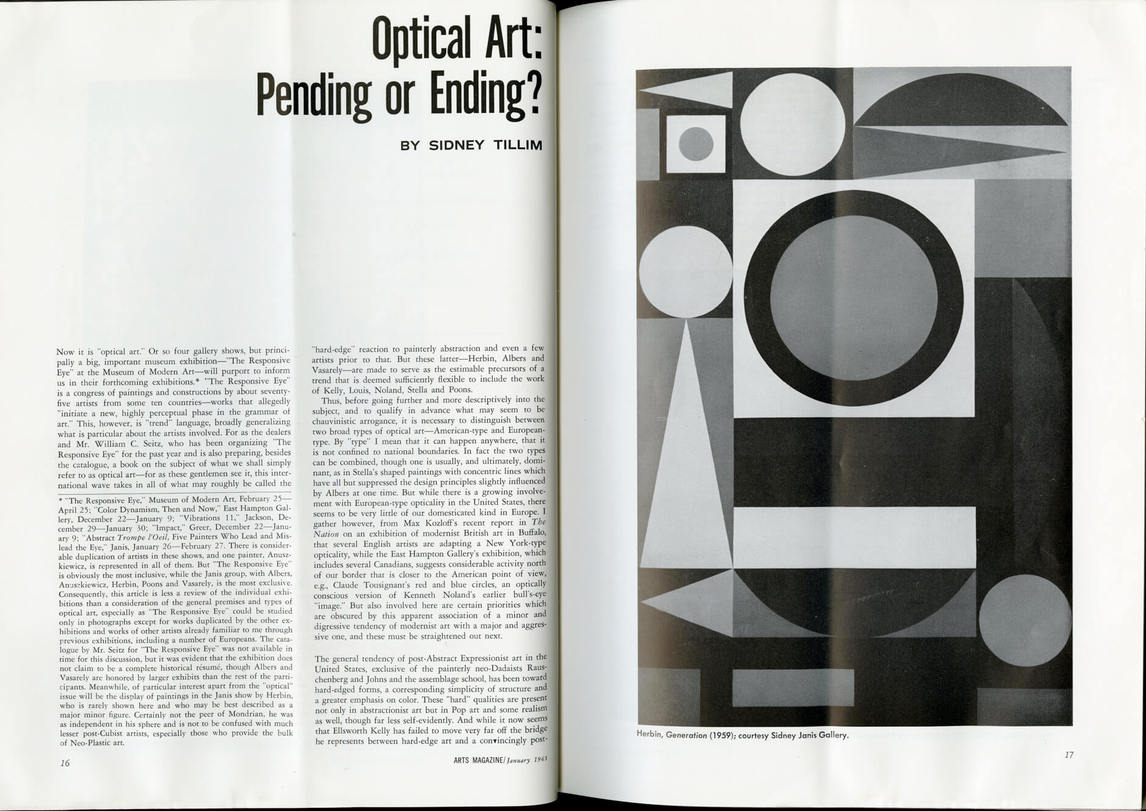

In anticipation of The Responsive Eye, the New York critic Sidney Tillim, in the January 1965 issue of Arts Magazine, attempted to discern some order within all the new hard-edge painting, dividing it into two categories: European-type and American-type painting. The first, along with most optical art, he judged old-fashioned because it was too dependent on prewar Cubism. The future for Tillim instead lay with American-type painting, which, with its background in Abstract Expressionism, had opened its compositions into expansive, flattened planes of colour fields.

In early 1965 Gaucher—unlike Guido Molinari (1933–2004) and Claude Tousignant (b. 1932), who had already had significant exhibitions in New York—had not sufficiently advanced his painting to be part of Tillim’s discussion. But in the wake of The Responsive Eye, Gaucher, along with Molinari and Tousignant, almost immediately became a regular participant in Op art shows across the United States, so that Tillim’s critical European-American distinctions could apply with equal aptness—or ineptness—to all three Montreal artists.

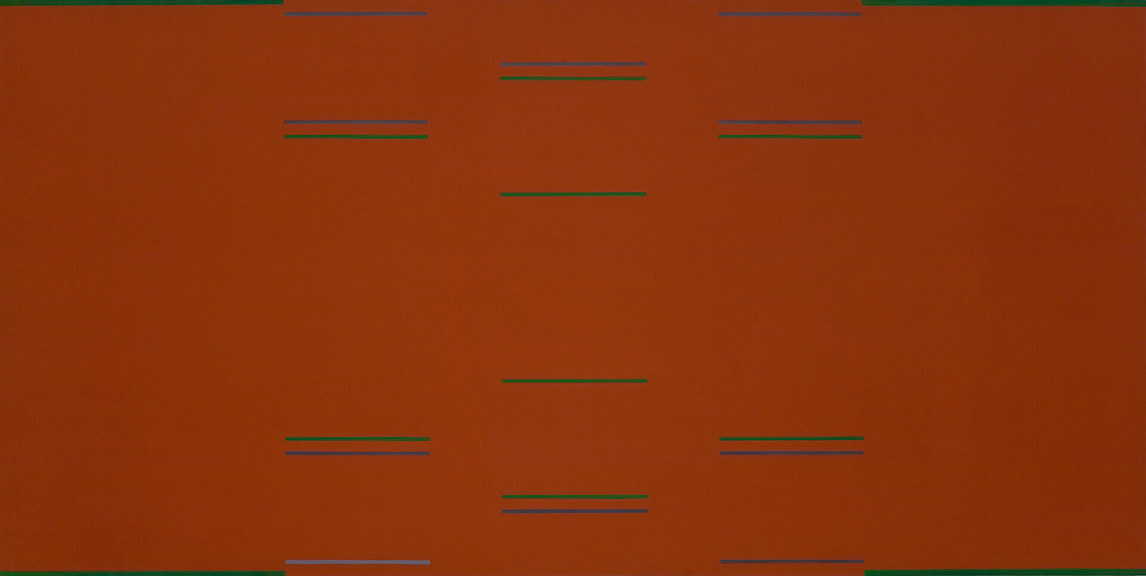

Where the Montrealers fit into his schema eluded Tillim and most New York critics, whose artistic taste largely followed Greenberg’s. The Canadians painted on an American scale, and they privileged pure unmodulated colour, as in Gaucher’s Dusk, Calm, Signals, 1966. But their edges were hard in a European way, razor-edged compared with the softer new American edges that let the colour fields they defined breathe with Matissian ease. The Canadians in contrast pulled their colour planes taut and abutted them tightly so that it was not their individual character as much as their interrelatedness that registered, and how their colours seemed to mutate under the roving eye.

In brief, if in New York the new “hard edge” was about the aesthetics of colour, in Montreal it was about colour’s dynamics. In this respect it is interesting to record that while Gaucher had his second solo exhibition at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York in September 1966, it would also be his last—Martha Jackson by then deciding that his work was straying too far from current trends in New York.

It was the stylistic rigour of the Montrealers that led Sidney Tillim and other American critics to dismiss them as mechanical, purged of subjectivity, and essentially bereft of sensual pleasure. The Montrealers themselves rejected being called optical artists, understanding their own ambitions in much larger terms, their colour dynamics a tool for immersing their viewers in the constant flux of human experience. Their art, they argued, could explore the world more profoundly than traditional painting because it was capable of embodying the structures that underlie daily existence.

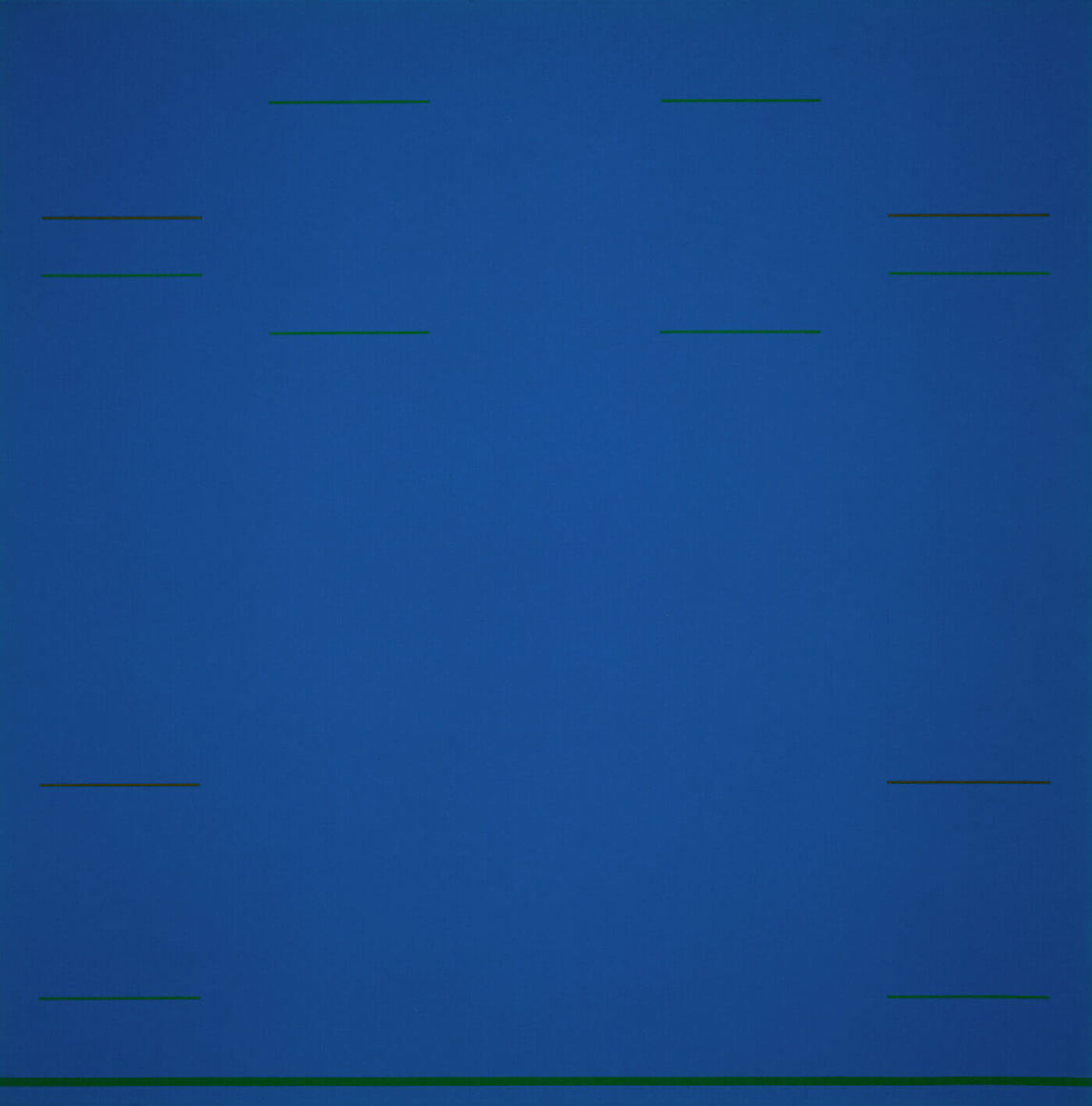

The Montreal post-Plasticiens thus constructed their paintings as fields of energy that operate according to the objective reality of the laws of colour and perception, their activity like a concentrated metaphor for the rhythms of real life. Thus the tautly constructed colour interactions and rhythmic movements of a painting like Gaucher’s Blue Raga, 1967, seek to focus in the viewer a specific set of responses, moments of intensified consciousness of such existential qualities of life as otherwise get trifled away by quotidian distractions.

But if Guido Molinari and Claude Tousignant undertook their painting largely from a secularly grounded world, Yves Gaucher added something else to the mix of Montreal hard-edge styles: not technically per se, but in his reach for a spiritual realm of experience, a quality he first consummately attained in his Grey on Grey paintings, which he began in 1967.

Gaucher as a North American Artist

Gaucher, like his fellow Montreal artists, and as much as any Post-Painterly Abstract painter, unabashedly saw himself in the forefront of modernist developments. But for historical and geographical reasons all the Montrealers drew for themselves a line of modernist descent that in a crucial way differed from that of the New Yorkers.

Gaucher’s story, of course, included Mark Rothko (1903–1970) and Barnett Newman (1905–1970), but it equally embraced Josef Albers (1888–1976) and Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), especially the New York Mondrian of the Boogie Woogie paintings. During Gaucher’s first visit to Paris in 1962, when he saw contemporary American painters like Rothko, Jasper Johns (b. 1930), and Morris Louis (1912–1962) in a European context, Gaucher fully came to understand that Paris was no longer a fountainhead for advanced art. Although French-speaking, Gaucher was a French-speaking North American. And if he and his fellow Montrealers were not American-type painters within the strictures of New York taste, they were, seen from a European perspective, recognizably North American painters.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements